As part of this work, the Ada Lovelace Institute, the University of Exeter’s Institute for Data Science and Artificial Intelligence, and the Alan Turing Institute developed six mock AI and data science research proposals that represent hypothetical submissions to a Research Ethics Committee. An expert workshop found that case studies are useful training resources for understanding common AI and data science ethical challenges. Their purpose is to prompt reflection on common research ethics issues and the societal implications of different AI and data science research projects. These case studies are for use by students, researchers, members of research ethics committees, funders and other actors in the research ecosystem to further develop their ability to spot and evaluate common ethical issues in AI and data science research.

Executive summary

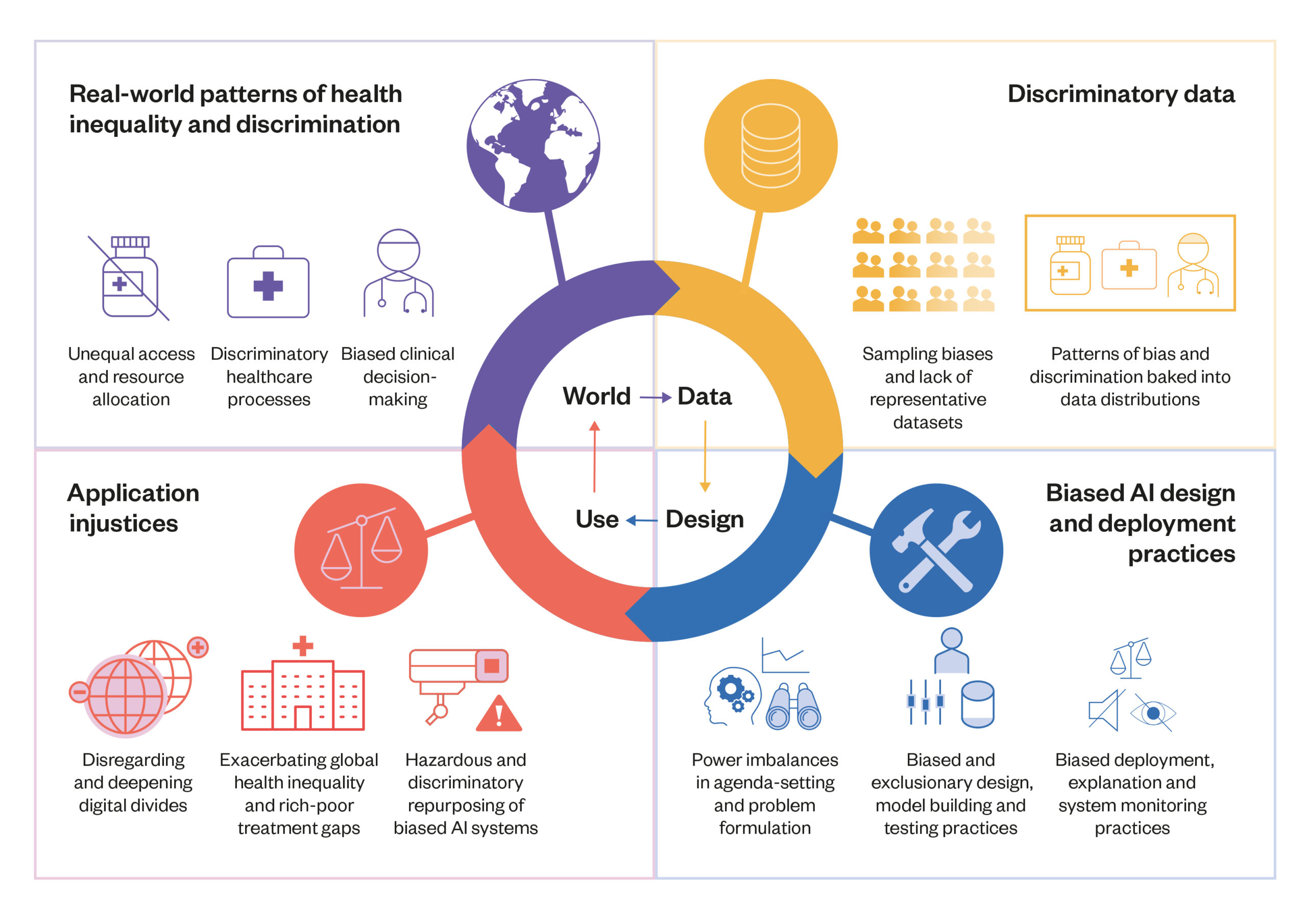

Research in the fields of artificial intelligence (AI) and data science is often quickly turned into products and services that affect the lives of people around the world. Research in these fields is used in the provision of public services like social care, determining which information is amplified on social media, what jobs or insurance people are offered, and even who is deemed a risk to the public by police and security services. There has been a significant increase in the volume of AI and data science research in the last ten years, with these methods now being applied to other scientific domains like history, economics, health sciences and physics.

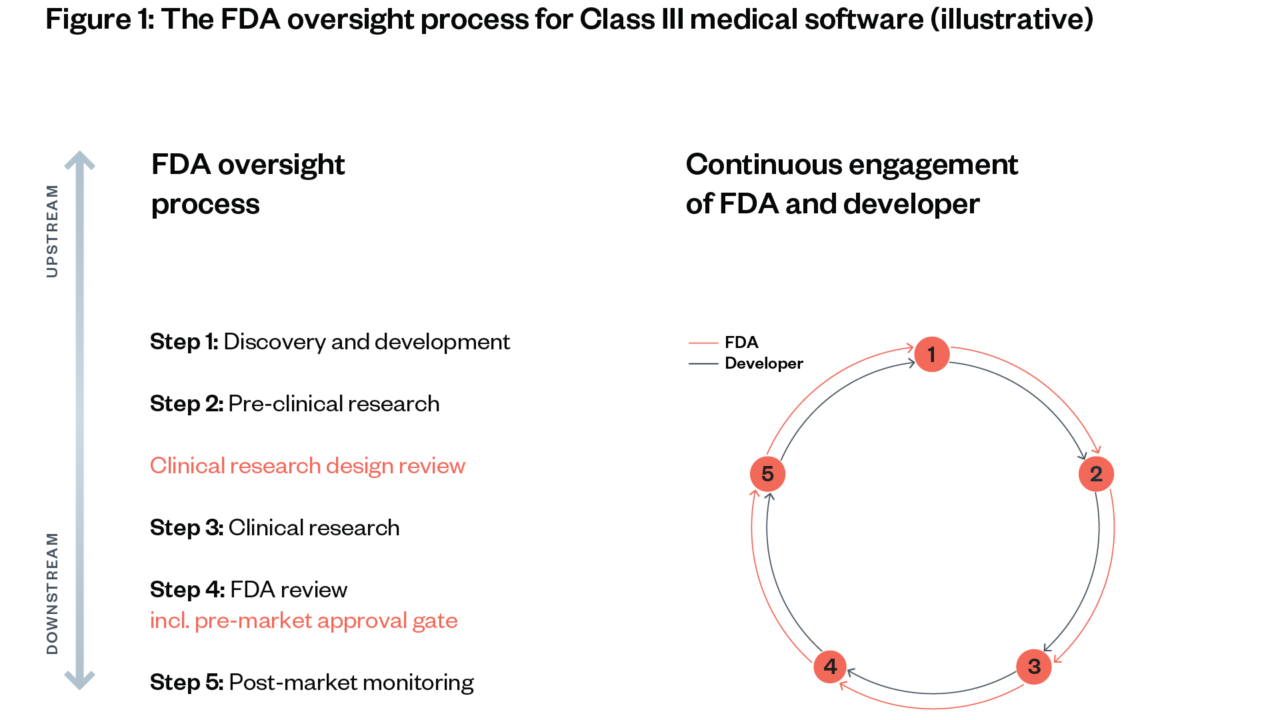

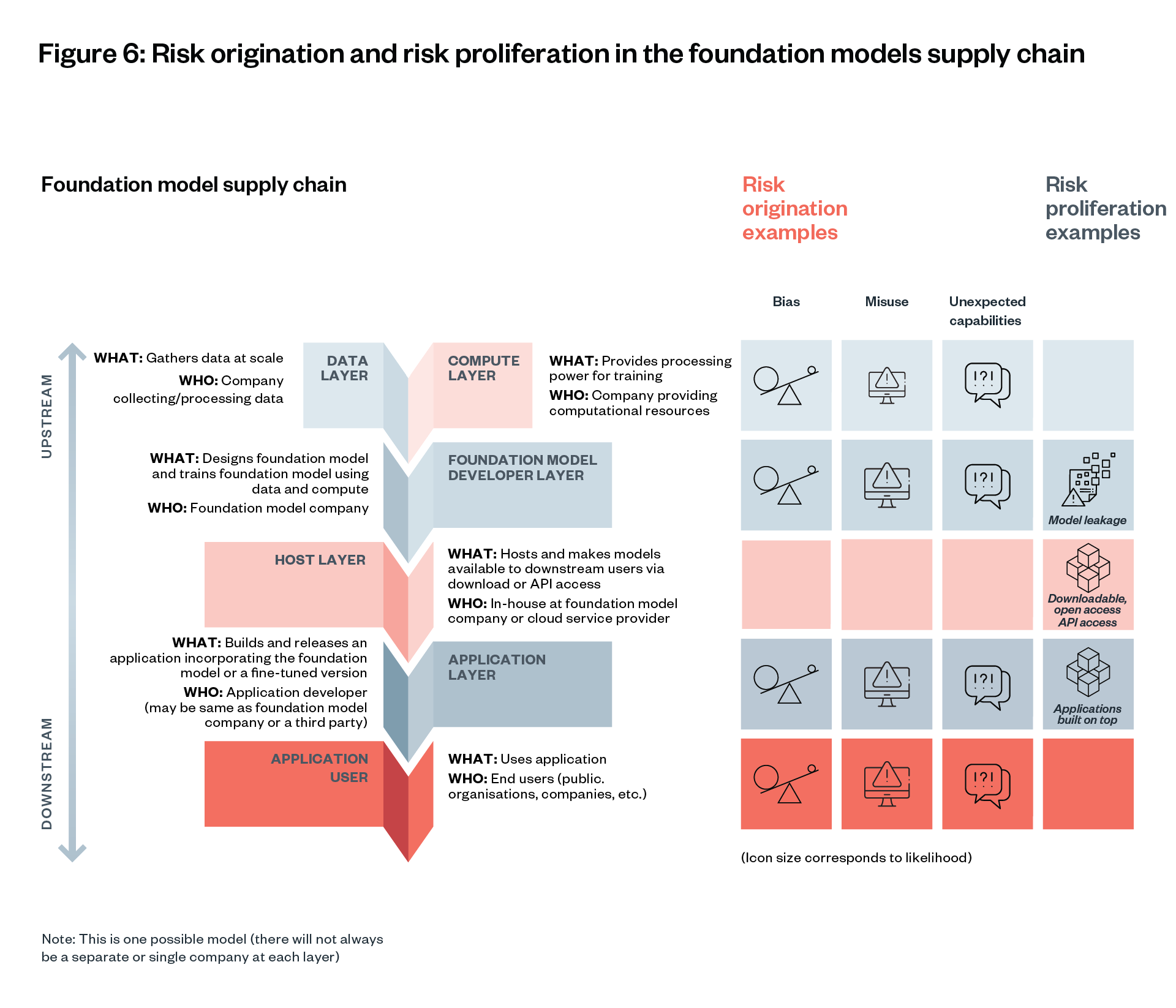

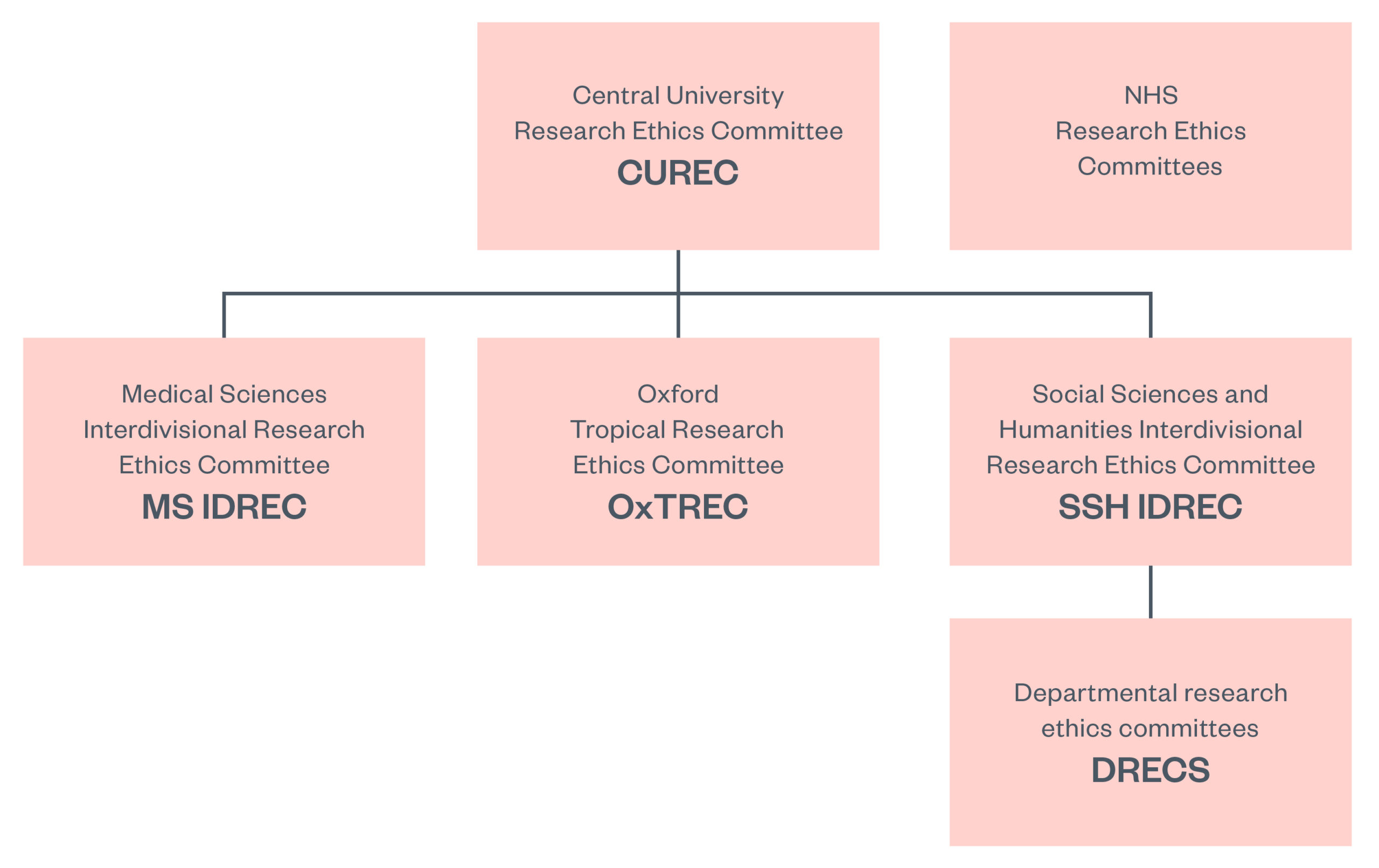

Figure 1: Number of AI publications in the world 2010-21[1]

Globally, the volume of AI research is increasing year-on-year and currently accounts for more than 4% of all published research.

Since products and services built with AI and data science research can have substantial effects on people’s lives, it is essential that this research is conducted safely and responsibly, and with due consideration for the broader societal impacts it may have. However, the traditional research governance mechanisms that are responsible for identifying and mitigating ethical and societal risks often do not address the challenges presented by AI and data science research.

As several prominent researchers have highlighted,[2] inadequately reviewed AI and data science research can create risks that are carried downstream into subsequent products,[3] services and research.[4] Studies have shown these risks can disproportionately impact people from marginalised and minoritised communities, exacerbating racial and societal inequalities.[5] If left unaddressed, unexamined assumptions and unintended consequences (paid forward into deployment as ‘ethical debt’[6]) can lead to significant harms to individuals and society. These harms can be challenging to address or mitigate after the fact.

Ethical debt also poses a risk to the longevity of the field of AI: if researchers fail to demonstrate due consideration for the broader societal implications of their work, it may reduce public trust in the field. This could lead to it becoming a domain that future researchers find undesirable to work in – a challenge that has plagued research into nuclear power and the health effects of tobacco.[7]

To address these problems, there have been increasing calls from within the AI and data science research communities for more mechanisms, processes and incentives for researchers to consider the broader societal impacts of their research.[8]

In many corporate and academic research institutions, one of the primary mechanisms for assessing and mitigating ethical risks is the use of Research Ethics Committees (RECs), also known in some regions as Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) or Ethics Review Committees (ERCs). Since the 1960s, these committees have been empowered to review research before it is undertaken and can reject proposals unless changes are made in the proposed research design.

RECs generally consist of members of a specific academic department or corporate institution, who are tasked with evaluating research proposals before the research begins. Their evaluations are based on a combination of normative and legal principles that have developed over time, originally in relation to biomedical human subjects research. A REC’s role is to help ensure that researchers justify their decisions for how research is conducted, thereby mitigating the potential harms they may pose.

However, the current role, scope and function of most academic and corporate RECs are insufficient for the myriad of ethical challenges that AI and data science research can pose. For example, the scope of REC reviews is traditionally only on research involving human subjects. This means that the many AI and data science projects that are not considered a form of direct intervention in the body or life of an individual human subject are exempt from many research ethics review processes.[9] In addition, a significant amount of AI and data science research involves the use of publicly available and repurposed datasets, which are considered exempt from ethics review under many current research ethics guidelines.[10]

If AI and data science research is to be done safely and responsibly, RECs must be equipped to examine the full spectrum of risks, harms and impacts that can arise in these fields.

In this report, we explore the role that academic and corporate RECs play in evaluating AI and data science research for ethical issues, and also investigate the kinds of common challenges these bodies face.

The report draws on two main sources of evidence: a review of existing literature on RECs and research ethics challenges, and a series of workshops and interviews with members of RECs and researchers who work on AI and data science ethics.

Challenges faced by RECs

Our evaluation of this evidence uncovered six challenges that RECs face when addressing AI and data science research:

Challenge 1: Many RECs lack the resources, expertise and training to appropriately address the risks that AI and data science pose.

Many RECs in academic and corporate environments struggle with inadequate resources and training on the variety of issues that AI and data science can raise. The work of RECs is often voluntary and unpaid, meaning that members of RECs may not have the requisite time or training to appropriately review an application in its entirety. Studies suggest that RECs are often viewed by researchers as compliance bodies rather than mechanisms for improving the safety and impact of their research.

Challenge 2: Traditional research ethics principles are not well suited for AI research.

RECs review research using a set of normative and legal principles that are rooted in biomedical, human-subject research practices, which operate under a researcher-subject relationship rather than a researcher-data subject relationship. This distinction has challenged traditional principles of consent, privacy and autonomy in AI research, and created confusion and challenges for RECs trying to apply these principles to novel forms of research.

Challenge 3: Specific principles for AI and data science research are still emerging and are not consistently adopted by RECs.

The last few years have seen an emerging series of AI ethics principles aimed at the development and deployment of AI systems. However, these principles have not been well adapted for AI and data science research practices, signalling a need for institutions to translate these principles into actionable questions and processes for ethics reviews.

Challenge 4: Multi-site or public-private partnerships can exacerbate existing challenges of governance and consistency of decision-making.

An increasing amount of AI research involves multi-site studies and public-private partnerships. This can lead to multiple REC reviews of the same research, which can highlight different standards in ethical review of different institutions and present a barrier to completing timely research.

Challenge 5: RECs struggle to review potential harms and impacts that arise throughout AI and data science research.

REC reviews of AI and data science research are ex ante assessments, done before research takes place. However, many of the harms and risks in AI research may only become evident at later stages of the research. Furthermore, many of the types of harms that can arise – such as issues of bias, or wider misuses of AI or data – are challenging for a single committee to predict. This is particularly true with the broader societal impacts of AI research, which require a kind of evaluation and review that RECs currently do not undertake.

Challenge 6: Corporate RECs lack transparency in relation to their processes.

Motivated by a concern to protect their intellectual property and trade secrets, many private-sector RECs for AI research do not make their processes or decisions publicly accessible and use strict non-disclosure agreements to control the involvement of external experts in their decision-making. In some extreme cases, this lack of transparency has raised suspicion of corporate REC processes from external research partners, which can pose a risk to the efficacy of public-private research partnerships.

Recommendations

To address these challenges, we make the following recommendations:

For academic and corporate RECs

Recommendation 1: Incorporate broader societal impact statements from researchers.

A key issue this report identifies is the need for RECs to incentivise researchers to engage more reflexively with the broader societal impacts of their research, such as the potential environmental impacts of their research, or how their research could be used to exacerbate racial or societal inequalities.

There have been growing calls within the AI and data science research communities for researchers to incorporate these considerations in various stages of their research. Some researchers have called for changes to the peer review process to require statements of potential broader societal impacts,[11] and some AI/machine learning (ML) conferences have experimented with similar requirements in their conference submission process.[12]

RECs can support these efforts by incentivising researchers to engage in reflexive exercises to consider and document the broader societal impacts of their research. Other actors in the research ecosystem (funders, conference organisers, etc.) can also incentivise researchers to engage in these kinds of reflexive exercises.

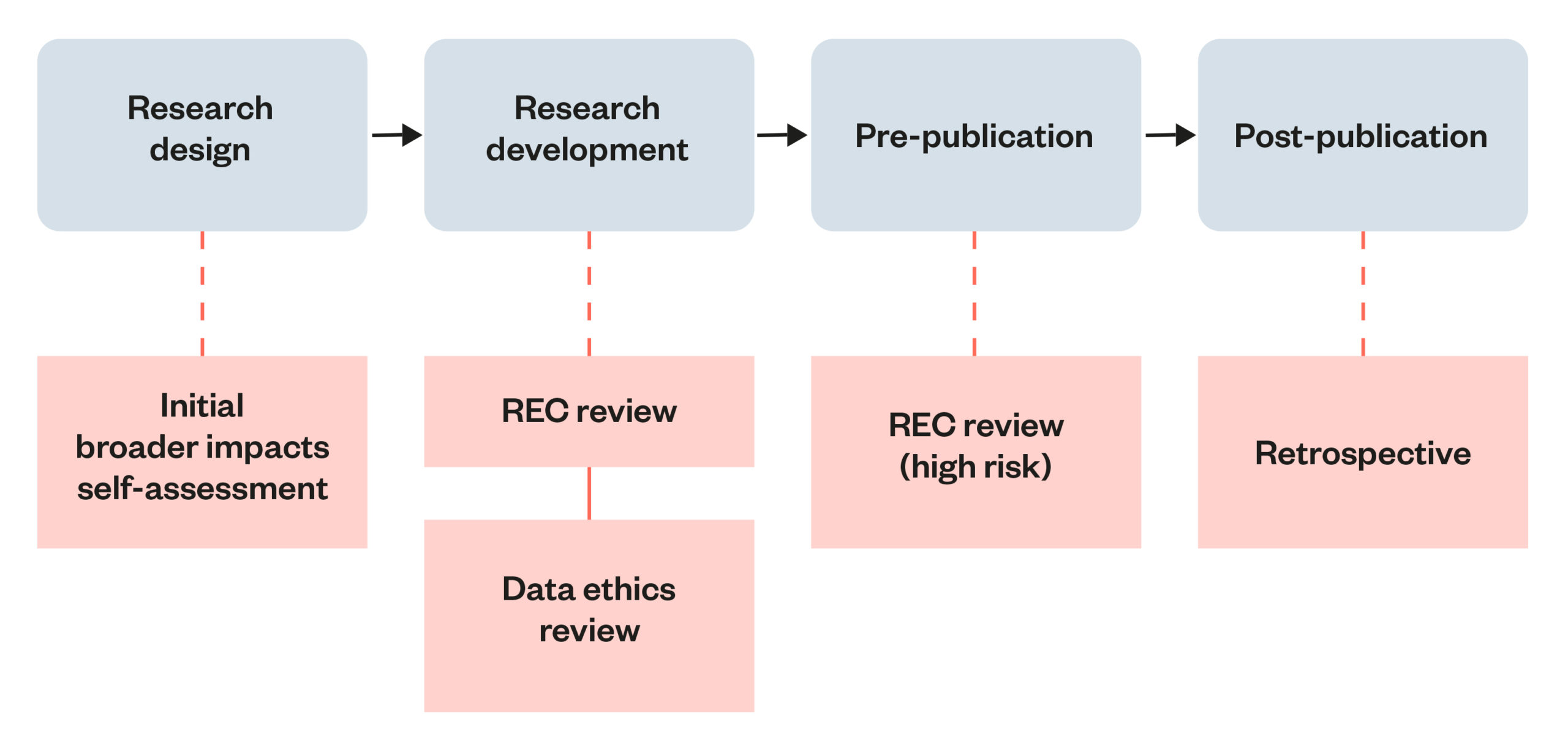

Recommendation 2: RECs should adopt multi-stage ethics review processes of high-risk AI and data science research.

Many of the challenges that AI and data science raise will arise in different stages of research. RECs should experiment with requiring multiple stages of evaluations of research that raises particular ethical concern, such as evaluations at the point of data collection and a separate evaluation at the point of publication.

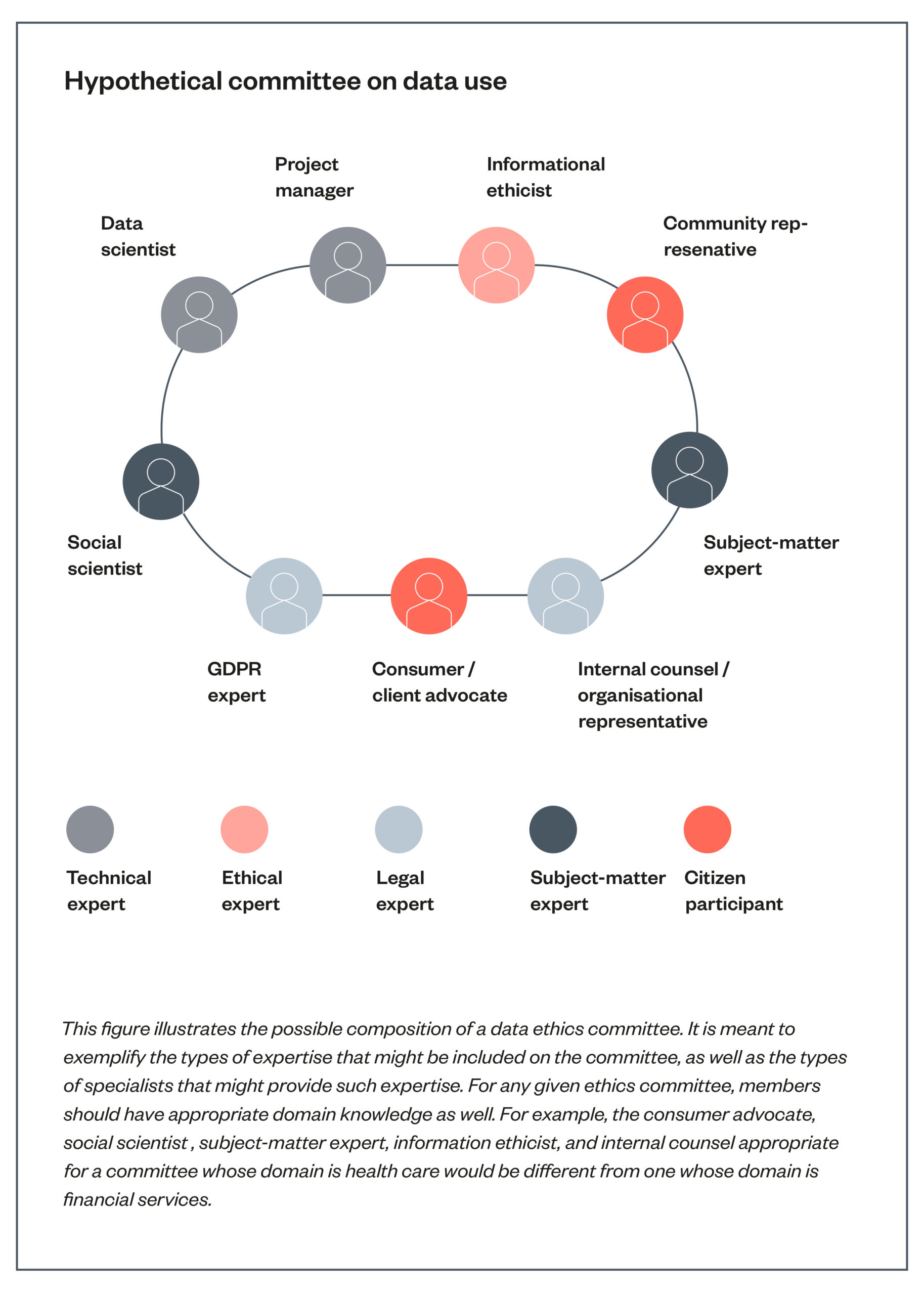

Recommendation 3: Include interdisciplinary and experiential expertise in REC membership.

Many of the risks that AI and data science research pose cannot be understood without engagement with different forms of experiential and subject-matter expertise. RECs must be interdisciplinary bodies if they are to address the myriad of issues that AI and data science can pose in different domains, and should incorporate the perspectives of individuals who will ultimately be impacted by the research.

For academic/corporate research institutions

Recommendation 4: Create internal training and knowledge-sharing hubs for researchers and REC members, and enable more cross-institutional knowledge sharing.

These hubs can provide opportunities for cross-institutional knowledge-sharing and ensure institutions do not develop standards of practice in silos. They should collect and share information on the kinds of ethical issues and challenges AI and data science research might raise, including case studies of research that raises challenging ethical issues. In addition to our report, we have developed a resource consisting of six case studies that we believe highlight some of the common ethical challenges that RECs might face.[13]

Recommendation 5: Corporate labs must be more transparent about their decision-making and do more to engage with external partners.

Corporate labs face specific challenges when it comes to AI and data science reviews. While many are better resourced and have experimented with broader societal impact thinking, some of these labs have faced criticism for being opaque about their decision-making processes. Many of these labs make consequential decisions about their research without engaging with local, technical or experiential expertise that resides outside their organisation.

For funders, conference organisers and other actors in the research ecosystem

Recommendation 6: Develop standardised principles and guidance for AI and data science research principles.

RECs currently lack standardised principles for evaluating AI and data science research. National research governance bodies like UKRI should work to create a new set of ‘Belmont 2.0’ principles[14] that offer some standardised approaches, guidance and methods for evaluating AI and data science research. Developing these principles should draw on a wide set of perspectives from different disciplines and communities who are impacted by AI and data science research, including multinational perspectives – particularly from regions that have been historically underrepresented in the development of past research ethics principles.

Recommendation 7: Incentivise a responsible research culture.

AI and data science researchers lack incentives to reflect on and document the societal impacts their research. Different actors in the research ecosystem can encourage ethical behaviour – funders, for example, can create requirements that researchers conduct a broader societal impact statement of their research in order to receive a grant, and conference organisers and journal editors can encourage researchers to include a broader societal impact statement when submitting research. By creating incentives throughout the research ecosystem, ethical reflection can become more desirable and rewarded.

Recommendation 8: Increase funding and resources for ethical reviews of AI and data science research.

There is an urgent need for institutions and funders to support RECs, including paying for the time of staff and funding external experts to engage in questions of research ethics.

Introduction

The academic fields of AI and data science research have witnessed an explosive growth in the last two decades. According to the Stanford AI Index, between 2015 and 2020, the number of AI publications on open-access publication database arXiv grew from 5,487 to over 34,376 (see also Figure 1). As of 2019, AI publications represented 3.8% of all peer-reviewed scientific publications, an increase from 1.3% in 2011.[15] The vast majority of research appearing in major AI conferences comes from academic and industry institutions based in the European Union, China and the United States of America.[16] AI and data science techniques are also being applied across a range of other academic disciplines such as history,[17] economics,[18] genomics[19] and biology.[20]

Compared to many other disciplines, AI and data science have a relatively fast research-to-product pipeline and relatively low barriers for use, making these techniques easily adaptable (though not necessarily well suited) to a range of different applications.[21] While these qualities have led AI and data science to be described as ‘more important than fire and electricity’ by some industry leaders,[22] there have been increased calls from members of the AI research community to require researchers to consider and address ‘failures of imagination’[23] of the potential broader societal impacts and risks of their research.

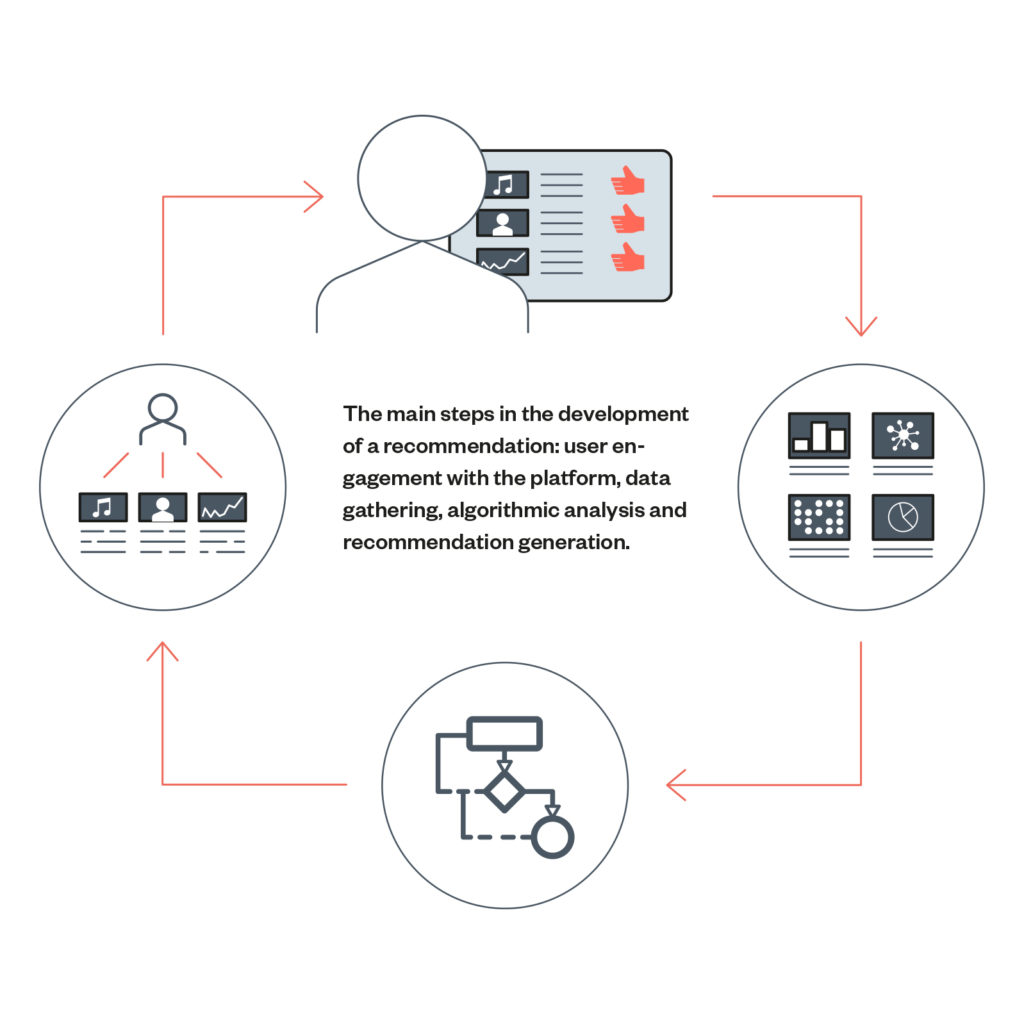

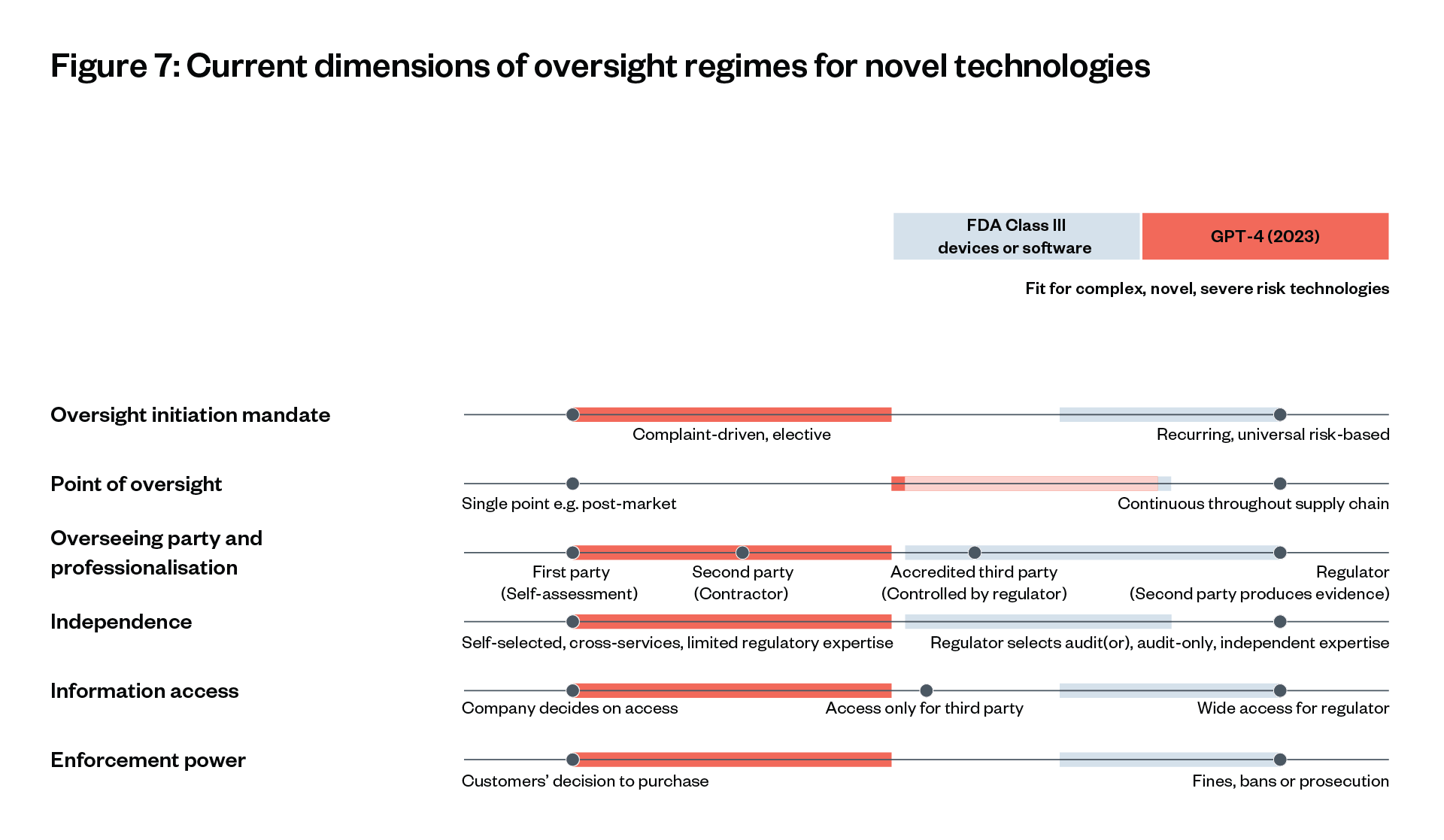

Figure 2: The research-to-product timeline

This timeline shows how short the research-to-product pipeline for AI can be. It took less than a year from the release of initial research in 2020 and 2021, exploring how to generate images from text inputs, to the first commercial products selling these services.

The sudden growth of AI and data science research has exacerbated challenges for traditional research ethics review processes, and highlighted that they are poorly set up to address questions of broader societal impact of research. Several high-profile instances of controversial AI research passing institutional ethics review include image recognition applications that claim to identify homosexuality,[24] criminality,[25] physiognomy[26] and phrenology.[27] Corporate labs have also experienced high-profile examples of unethical research being approved, including a Microsoft chatbot capable of spreading disinformation,[28] and a Google research paper that contributed to the surveillance of China’s Uighur population.[29]

In research institutions, the role of assessing for research ethics issues tends to fall on Research Ethics Committees (RECs), also known in some regions as Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) or Ethics Review Committees (ERCs). Since the 1960s, these committees have been empowered to reject research from being undertaken unless changes are made in the proposed research design.

These committees generally consist of members of a specific academic department or corporate institution, who are responsible for evaluating research proposals before the research begins. Their evaluations combine normative and legal principles, originally linked to biomedical human subjects research, that have developed over time.

Traditionally, RECs only consider research involving human subjects and only consider questions concerning how the research will be conducted. While they are not the only ‘line of defence’ against unethical practices in research, they are the primary actor responsible for mitigating potential harms to research subjects in many forms of research.

The increasing prominence of AI and data science research poses an important question: are RECs well placed and adequately set up to address the challenges that AI and data science research pose? This report explores these challenges that public and private-sector RECs face in evaluations of research ethics and broader societal impact issues in AI and data science research.[30] In doing so, it aims to help institutions that are developing AI research review processes take a holistic and robust approach for identifying and mitigating these risks. It also seeks to provide research institutions and other actors in the research ecosystem – funders, journal editors and conference organisers – with specific recommendations for how they can address these challenges.

This report seeks to address four research questions:

- How are RECs in academia and industry currently structured? What role do they play in the wider research ecosystem?

- What resources (e.g. moral principles, legal guidance, etc.) are RECs using to guide their reviews of research ethics? What is the scope of these reviews?

- What are the most pressing or common challenges and concerns that RECs are facing in evaluations of AI and data science research?

- What changes can be made so that RECs and the wider AI and data science research community can better address these challenges?

To address these questions, this report relied on a review of the literature on RECs, research ethics and broader societal impact questions in AI. The report also draws on a series of workshops with 42 members of public and private AI and data science research institutions in May 2021, along with eight interviews with experts in research ethics and AI issues. More information on our methodology can be found in ‘Methodology and limitations’.

This report begins with an introduction to the history of RECs, how they are commonly structured, and how they commonly operate in corporate and academic environments for AI and data science research. The report then discusses six challenges that RECs face – some of which are longstanding issues, others of which are exacerbated by the rise of AI and data science research. We conclude the paper with a discussion of these findings and eight recommendations for actions that RECs and other actors in the research ecosystem can take to better address the ethical risks of AI and data science research.

Context for Research Ethics Committees and AI research

This section provides a brief history of modern research ethics and Research Ethics Committees (RECs), discusses their scope and function, and highlights some differences between how they operate in corporate and academic environments. It places RECs in the context of other actors in the ‘AI research ecosystem’, such as organisers of AI and data science conferences, or editors of AI journal publications who set norms of behaviour and incentives within the research community. Three key points to take away from this chapter are:

- Modern research ethics questions are mostly focused on ethical challenges that arise in research methodology, and exclude consideration of the broader societal impacts of research.

- Current RECs and research ethics principles stem from biomedical research, which analyses questions of research ethics through a lens of patient-clinician relationships and is not well suited for the more distanced relationship in AI and data science between a researcher and data subject.

- Academic and corporate RECs in AI research share common aims, but with some important differences. Corporate AI labs tend to have more resources, but may also be less transparent about their processes.

What is a REC, and what is its scope and function?

Every day, RECs review applications to undertake research for potential ethical issues that may arise. Broadly defined, RECs are institutional bodies made up of members of an institution (and, in some instances, independent members outside that institution) who are charged with evaluating applications to undertake research before it begins. They make judgements about the suitability of research, and have the power to approve researchers to go ahead with a project or request that changes are made before research is undertaken. Many academic journals and conferences will not publish or accept research that fails to meet a review by a Research Ethics Committee (though as we will discuss below, not all research requires review).

RECs operate with two purposes in mind:

- To protect the welfare and interests of prospective and current research participants and minimise risk of harm to them.

- To promote ethical and societally valuable research.

In meeting these aims, RECs traditionally conduct an ex ante evaluation only once, before a research project begins. In understanding what kinds of ethical questions RECs evaluate for, it is also helpful to disentangle three distinct categories of ethical risks in research: [31]

- Mitigating research process harms (often confusingly called ‘research ethics’).

- Research integrity.

- Broader societal impacts of research (also referred to as Responsible Research and Innovation, or RRI).

The scope of REC evaluations is entirely on questions of mitigating the ethical risks from research methodology, such as how the researcher intends to protect the privacy of a participant, anonymise their data or ensure they have received informed consent.[32] In their evaluations, RECs may look at whether the research poses a serious risk to interests and safety of research subjects, or if the researchers are operating in accordance with local laws governing data protection and intellectual property ownership of any research findings.

REC evaluations may also probe on whether the researchers have assessed and minimised potential harm to research participants, and seek to balance this against the benefits of the research for society at large.[33] However, there are limitations to the aim of promoting ethical and societally valuable research. There are few frameworks for how RECs can consider the benefit of research for society at large. Additionally, this concept of mitigating methodological risks does not extend to considerations of whether the research poses risks to society at large, or to individuals beyond the subjects of that research.

| Three different kinds of ethical risks in research

1. Mitigating research process (also known as ‘research ethics’): The term research ethics refers to the principles and processes governing how to mitigate the risks to research subjects. Research ethics principles are mostly concerned with the protection, safety and welfare of individual research participants, such as gaining their informed consent to participate in research or anonymising their data to protect their privacy.

2. Research integrity: These are principles governing the credibility and integrity of the research, including which whether it is intellectually honest, transparent, robust, and replicable.[34] In most fields, research integrity is evaluated via the peer review process after research is completed.

3. Broader societal impacts of research: This refers to the potential positive and negative societal and environmental implications of research, including unintended uses (such as misuse) of research. A similar concept is Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI) which refers to steps that researchers can undertake to anticipate and address the potential downstream risks and implications of their research.[35] |

RECs, however, often do not evaluate for questions of research integrity, which is concerned with whether research is intellectually honest, transparent, robust and replicable.[36] These can include questions relating to whether data has been fabricated or misrepresented, whether research is reproducible, stating the limitations and assumptions of the research, and disclosing conflicts of interests.[37] The intellectual integrity of researchers is important for ensuring public trust in science, which can be eroded in cases of misconduct.[38]

Some RECs may consider complaints about research integrity issues that arise after research has been published, but these issues are often not considered as part of their ethics reviews. RECs may, however, assess a research applicant’s bona fides to determine if they are someone who appears to have integrity (such as if they have any conflicts of interest with the subject of their study). Usually, questions of research integrity are left to other actors in the research ecosystem, such as peer reviewers and whistleblowers who may notify a research institution or the REC of questionable research findings or dishonest behaviour. Other governance mechanisms for addressing research integrity issues include publishing the code or data of the research so that others may attempt to reproduce findings.

Another area of ethical risks that contemporary RECs do not evaluate for (but which we argue they should) is the responsibility of researchers to consider the broader societal effects of their research on society.[39] This is referred to as Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI), which moves beyond concerns of research integrity and is: ‘an approach that anticipates and assesses potential implications and societal expectations with regard to research and innovation, with the aim to foster the design of inclusive and sustainable research and innovation’.[40]

RRI is concerned with the integration of mechanisms of reflection, anticipation and inclusive deliberation around research and innovation, and relies on individual researchers to incorporate these practices in their research. This includes analysing potential economic, societal or environmental impacts that arise from research and innovation. RRI is a more recent development that emerged separately to RECs, stemming in part from the Ethical Legal and Societal Implications Research (ELSI) programme in the 1990s, which was established to research the broader societal implications of genomics research.[41]

Traditionally, RECs are usually not well equipped to deal with assessing subsequent uses of research, or their impacts on society. RECs often lack the capacity or remit to monitor the downstream uses of research, or to act as an ‘observatory’ for identifying trends in the use or misuse of research they reviewed at inception. This is compounded by the decentralised and fragmentary nature of RECs, which operate independently of each other and often do not evaluate each other’s work.

What principles do RECs rely on to make judgements about research ethics?

In their evaluations, RECs rely on a variety of tools, including laws like the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which cover data protection issues and some discipline-specific norms. At the core of all Research Ethics Committee evaluations, there are a series of moral principles that have evolved over time. These principles largely stem from the biomedical sciences, and have been codified, debated and edited by international bodies like the World Medical Association and World Health Organisation. The biomedical model of research ethics is the foundation for how concepts like autonomy and consent were encoded in law,[42] which often motivate modern discussions about privacy.

Some early modern research ethics codes, like the Nuremberg Principles and the Belmont Report, were developed in response to specific atrocities and scandals involving biomedical research on human subjects. Other codes, like the Declaration of Helsinki, developed out of a field-wide concern to self-regulate before governments stepped in to regulate.[43]

Each code and declaration seeks to address specific ethical issues from a particular regional and historical context. Nonetheless, they are united by two aspects. Firstly, they frame research ethics questions in a way that assumes a clear researcher-subject relationship. Secondly, they all seek to standardise norms of evaluating and mitigating the potential risks caused by research processes, to support REC decisions becoming more consistent between different institutions.

Historical principles governing research ethics

Nuremberg Code: The Nuremberg trials occurred in 1947 and revealed horrific and inhumane medical experimentation by Nazi scientists on human subjects, primarily concentration camp prisoners. Out of concern that these atrocities might further damage public trust in medical professionals and research,[44] the judges in this trial included a set of universal principles for ‘permissible medical experiments’ in their verdict, which would later become known as the Nuremberg Code.[45] The Code lists ten principles that seek to ensure individual participant rights are protected and outweigh any societal benefit of the research.

Declaration of Helsinki: Established by World Medical Association (WMA), the Helsinki Declaration seeks to articulate universal principles for human subjects research and clinical research practice. The WMA is an international organisation representing physicians from across the globe. The Helsinki Declaration has been updated repeatedly since its first iteration in 1964, with major updates occurring in 1975, 2000 and 2008. It specifies five basic principles for all human subjects research, as well as further principles specific to clinical research.

Belmont Report: This report was written in response to several troubling incidents in the USA, in which patients participating in clinical trials were not adequately informed about the risks involved. These include a 40-year-long experiment by the US Public Health Service and the Tuskegee Institute that sought to study untreated syphilis in Black men. Despite having over 600 participants (399 with syphilis, 201 without), the participants were deceived about the risks and nature of experiment and were not provided with a cure for the disease after it had been developed in the 1940s.[46] These developments led to the United States’ National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research to publish the Belmont Report in 1979, which listed several principles for research to follow: justice, beneficence and respect for persons.[47]

Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences Guidelines (CIOMS): CIOMS was formed in 1949 by the World Health Organisations and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO), and is made up of a range of biomedical member organisations from across the world. In 2016, it published the International Ethical Guidelines for Health-Related Research Involving Humans,[48] which includes specific requirements for research involving vulnerable persons and groups, compensation for research participants, and requirements for researchers and health authorities to engage potential participants and communities in a ‘meaningful participatory process’ in various stages of research.[49] |

Biomedical research ethics principles touch on a wide variety of issues, including autonomy and consent. The Nuremberg Code specified that, for research to proceed, a researcher must have consent given (i) voluntarily by a (ii) competent and (iii) informed subject (iv) with adequate comprehension. At the time, consent was understood as only applicable to healthy, non-patient participants, and thus excluded patients in clinical trials, access to patient information like medical registers and participants (like children or people with a cognitive impairment) who are unable to give consent.

Subsequent research ethics principles have adapted to these scenarios with methods such as legal guardianship, group or community consent, and broad or blanket consent.[50] Under the Helsinki Declaration, consent must be given in writing and states that research subjects can give consent only if they have been fully informed of the study’s purpose, the methods, risks and benefits involved, and their right to withdraw.[51] In all these conceptions of consent, there is a clearly identifiable research subject, who is in some kind of direct relationship with a researcher.

Another area that biomedical research principles touch on is the risk and benefit of research for research subjects. While the Nuremberg Code was unambiguous about the protection of research subjects, the Helsinki Declaration introduced the concept of benefit from research in proportion to risk.[52] The 1975 document and other subsequent revisions reaffirmed that, ‘while the primary purpose of medical research is to generate new knowledge, this goal can never take precedence over the rights and interests of individual research subjects.’[53]

However, Article 21 recommends that research can be conducted if the importance of its objective outweighs the risks to participants, and Article 18 states that a careful assessment of predictable risks to participants must be undertaken in comparison to potential benefits for individuals and communities.[54] The Helsinki Declaration lacks clarity on what constitutes an acceptable, or indeed ‘predictable’ risk and how the benefits would be assessed, and therefore leaves the challenge of resolving these questions to individual institutions.[55] The CIOMS guidance also suggests RECs should consider the ‘social value’ of health research in considering a cost/benefit analysis.

The Belmont Report also addressed the trade-off between societal benefit and individual risk, offering specific ethics principles to guide scientific research that include ‘respects for persons’, ‘beneficence’ and ‘justice’.[56] The principle of ‘respect for persons’ is broken down into respect for the autonomy of human research subjects and requirements for informed consent. The principle of ‘beneficence’ requires the use of the best possible research design to maximise benefits and minimise harms, and prohibits any research that is not backed by a favourable risk-benefit ratio (to be determined by a REC). Finally, the principle of ‘justice’ stipulates that the risks and benefits of research are distributed fairly, research subjects are selected through fair procedures, and to avoid any exploitation of vulnerable populations.

The Nuremberg Code created standardised requirements to identify who bears responsibility for identifying and addressing potential ethical risks of research. For example, the Code stipulates that the research participants have the right to withdraw (Article 9), but places responsibility on the researchers to evaluate and justify any risks in relation to human participation (Article 6), to minimise harm (Articles 4 and 7) and to stop the research if it is likely to cause injury or death to participants (Articles 5 and 10).[57] Similar requirements exist in other biomedical ethical principles like the Helsinki Declaration, which extends responsibility for assessing and mitigating ethical risks to both researchers and RECs.

A brief history of RECs in the USA and the UKRECs are a relatively modern phenomenon in the history of academic research, and their origins stem from early biomedical research initiatives of the 1970s. The 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, an initiative by the World Medical Association (WMA) to articulate universal principles for human subjects research and clinical research practice, declared the ultimate arbiter for making assessments of ethical risk and benefit were specifically appointed, independent research ethics committees who are given the responsibility to assess the risk of harm to research subjects and the management of those risks.

In the USA, the National Research Act of 1974 requires Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval for all human subjects research projects funded by the US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (DHEW).[58] This was extended in 1991 under the ‘Common Rule’ so that any research involving human subjects that is funded by the federal government must undergo an ethics review by an IRB. There are certain exceptions for what kinds of research will go before an IRB, including research that involves the analysis of data that is publicly available, privately funded research, and research that involves secondary analysis of existing data (such as the use of existing ‘benchmark’ datasets that are commonly used in AI research).[59]

In the UK, the first RECs began operating informally around 1966, in the context of clinical research in the National Health Service (NHS), but it was not until 1991 that RECs were formally codified. In the 1980s, the UK expanded the requirement for REC review beyond clinical health research into other disciplines. Academic RECs in the UK began to spring up around this same time, with the majority coming into force after the year 2000.

UK RECs in the healthcare and clinical context are coordinated and regulated by the Health Research Authority, which has passed guidance for how medical healthcare RECs should be structured and operate, including the procedure of submitting an ethics application and the process of ethics review.[60] This guidance allows for greater harmony across different health RECs and better governance for multi-site research projects, but this guidance does not extend to RECs in other academic fields. Some funders such as the UK’s Economic and Social Research Council have also released research ethics guidelines for non-health projects to undergo certain ethics review requirements if the project involves human subjects research (though the definition of human subjects research is contested).[61] |

RECs in academia

While RECs broadly seek to protect the welfare and interests of research participants and promote ethical and societally valuable research, there are some important distinctions to draw between the function and role of a REC in academic institutions compared to private-sector AI labs.

Where are RECs located in universities and research institutes?

Academic RECs bear a significant amount of the responsibility for assessing research involving human participants, including the scrutiny of ethics applications from staff and students. Broadly, there are two models of RECs used in academic research institutions:

- Centralised: A single, central REC is responsible for all research ethics applications, including the development of ethics policies and guidance.

- Decentralised: Schools, faculties or departments have their own RECs for reviewing applications, while a central REC maintains and develops ethics policies and guidance.[62]

RECs can be based at the institutional level (such as at universities), or at the regional and federal level. Some RECs may also be run by non-academic institutions, who are charged with reviewing academic research proposals. For example, academic health research in the UK may undergo review by RECs run by the National Health Service (NHS), sometimes in addition to review by the academic body’s own REC. In practice, this means that publicly funded health research proposals may seek ethics approval from one of the 85 RECs run by the NHS, in addition to non-NHS RECs run by various academic departments.[63]

A single, large academic institution, such as the University of Cambridge, may have multiple committees running within it, each with a different composition and potentially assessing different kinds of fields of research. Depending on the level of risk and required expertise, a research project may be reviewed by a local REC, school-level REC or may also be reviewed by a REC at the university level.[64]

For example, Exeter University has a central REC and 11 devolved RECs at college or discipline level. The devolved RECS report to the central REC, which is accountable to the University Council (governing body). Exeter University also implements a ‘dual assurance’ scheme, with an independent member of the university’s governing body providing oversight of the implementation of their ethics policy. The University of Oxford also relies on a cascading system of RECs, which can escalate concerns up the chain if needed, and which may include department and domain-specific guidance for certain research ethics issues.

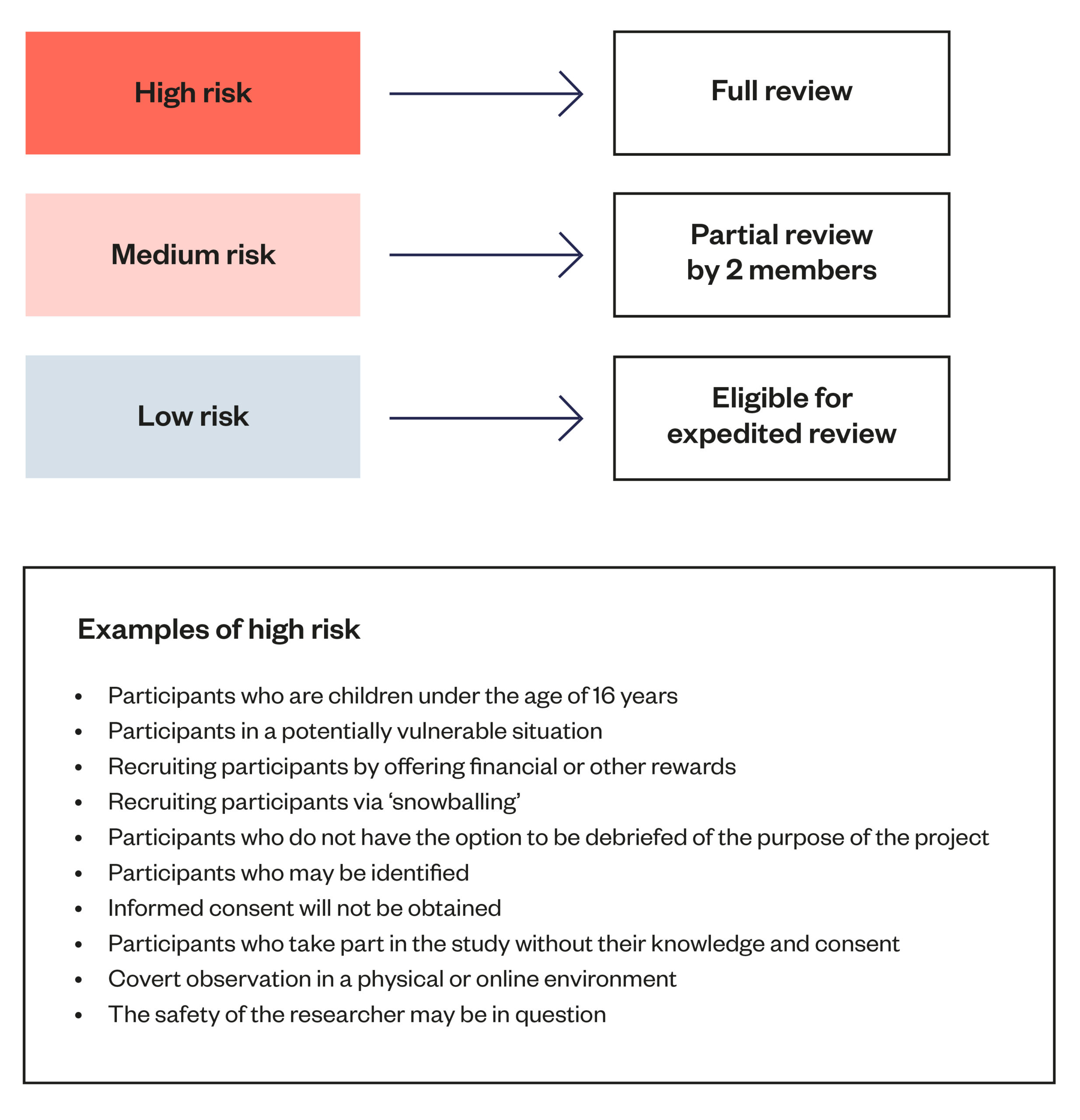

Figure 3: The cascade of RECs at the University of Oxford[65]

This figure shows how one academic institution’s RECs are structured, with a central REC and more specialised committees.

What is the scope and role of academic RECs?

According to a 2004 survey of UK academic REC members, they play four principal roles:[66]

- Responsibility for ethical issues relating to research involving human participants, including maintaining standards and provision of advice to researchers.

- Responsibility for ensuring production and maintenance of codes of practice and guidance for how research should be conducted.

- Ethical scrutiny of research applications from staff and, in most cases, students.

- Reporting and monitoring of instances of unethical behaviour to other institutions or academic departments.

Academic RECs often include a function for intaking and assessing reports of unethical research behaviour, which may lead to disciplinary action against staff or students.

When do ethics reviews take place?

RECs form a gateway through which researchers apply to obtain ethics approval as a prerequisite for further research. At most institutions, researchers will submit their work for ethics approval before conducting the study – typically at the early stages in the research lifecycle, such as at the planning stage or when applying for research grants. This means RECs only consider an anticipatory assessment of ethical risks that the proposed method may raise.

This assessment relies on both ‘testimony’ from research applicants who document what they believe are the material risks, and a review by REC members themselves who assess the validity of that ‘testimony’, provide an opinion of what they envision the material risks of the research method might be, and how those risks can be mitigated. There is limited opportunity for revising these assessments once the research is underway, and that usually only occurs if a REC review identifies a risk or threat and asks for additional information. One example of an organisation that takes a different approach is the Alan Turing Institute, which developed a continuous integration approach with reviews taking place at various stages throughout the research life cycle.[67]

The extent of a REC’s review will vary depending on whether the project has any clearly identifiable risks to participants, and many RECs apply a triaging process to identify research that may pose particularly significant risks. RECs may use a checklist that asks a researcher whether their project involves particularly sensitive forms of data collection or risk, such as research with vulnerable population groups like children, or research that may involve deceiving research participants (such as creating a fake account to study online right-wing communities). If an application raises one of these issues, it must undergo a full research ethics review. In cases where a research application does not involve any of these initial risks, it may undergo an expedited process that involves a review of only some factors of the application such as its data governance practices.[68]

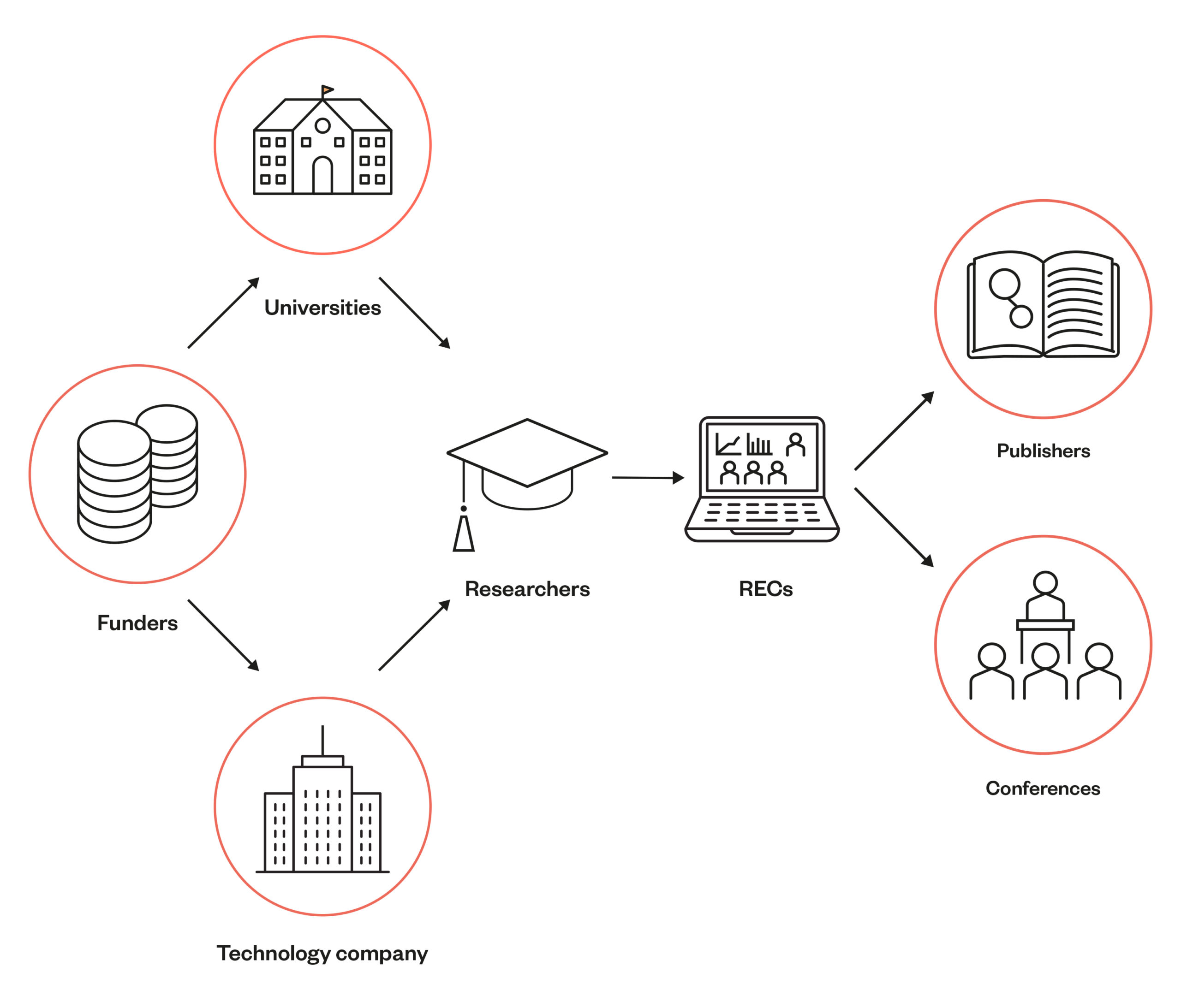

Figure 4: Example of the triaging application intake process for a UK University REC

If projects meet certain risk criteria, they may be subject to a more extensive review by the full committee. Lower-risk projects may be approved by only one or two members of the committee.

During the review, RECs may offer researchers advice to mitigate potential ethical risks. Once approval is granted, no further checks by RECs are required. This means that there is no mechanism for ongoing assessment of emerging risks to participants, communities or society as the research progresses. As the focus is on protecting individual research participants, there is no assessment of potential long-term downstream harms of research.

Composition of academic RECs

The composition of RECs varies between and even within various institutions. In the USA, RECs are required under the ‘common rule’ to have a minimum of five members with a variety of professional backgrounds, to be made up of people from different ethnic and cultural backgrounds, and to have at least one member who is independent from the institution. In the UK, the Health Research Authority recommends RECs have 18 members, while the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) recommends at least seven.[69] RECs operate on a voluntary basis, and there is currently no financial compensation for REC members, nor any other rewards or recognition.

Some RECs are comprised of an interdisciplinary board of people who bring different kinds of expertise to ethical reviews. In theory, this is to provide a more holistic review of research that ensures perspectives from different disciplines and life experiences are factored into a decision. RECs in the clinical context in the UK, for example, must involve both expert members with expertise in the subject area and ‘lay members’, which refers to people ‘who are not registered healthcare professionals and whose primary professional interest is not in clinical research’.[70] Additional expertise can be sourced on an ad hoc basis.[71] The ESRC also further emphasises that RECs should be multi-disciplinary and include ethnic and gender diversity.[72] According to our expert workshop participants, however, many RECs that are located within a specific department of faculty are often not multi-disciplinary and do not include lay members, although specific expertise might be requested when needed.

The Secure Anonymised Information Linkage databank (SAIL)[73] offers one example of a body that does integrate lay members in their ethics review process. Their review criteria include data governance issues and risks of disclosure, but also whether the project contributes to new knowledge, and whether it serves the public good by improving health, wellbeing and public services.

RECs within the technology industry

In the technology industry, several companies with AI and data science research divisions have launched internal ethics review processes and accompanying RECs, with notable examples being Microsoft Research, Meta Research and Google Brain. In our workshop and interviews with participants, members of corporate RECs we spoke with noted some key facets of their research review processes. It is important, however, to acknowledge that little publicly available information exists on corporate REC practices, including their processes and criteria for research ethics review. This section reflects statements made by workshop and interview participants, and some public reports of research ethics practices in private-sector labs.

Scope

According to our participants, corporate AI research RECs tend to take a broader scope of review than traditional academic RECs. Their reviews may extend beyond research ethics issues and into questions of broader societal impact. Interviews with developers of AI ethics review practices in industry suggested a view that traditional REC models can be too cumbersome and slow for the quick pace of the product development life cycle.

At the same time, ex ante review does not provide good oversight on risks that emerge during or after a project. To address this issue, some industry RECs have sought to develop processes that focus beyond protecting individual research subjects and include considerations for the broader downstream effects for population groups or society, as well as recurring review throughout the research/product lifecycle.[74]

Several companies we spoke with have specific RECs that review research involving human subjects. However, as one participant from a corporate REC noted, ‘a lot of AI research does not involve human subjects’ or their data, and may focus instead on environmental data or other types of non-personal information. This company relied on separate ethics review process for such cases that considers (i) the potential broader impact of the research and (ii) whether the research aligns with public commitments or ethical principles the company has made.

According to a law review article on their research ethics review process, Meta (previously known as Facebook) claims to consider the public contribution of knowledge of research and whether it may generate positive externalities and implications for society.[75] A workshop participant from another corporate REC noted that ‘the purpose of [their] research is to have societal impact, so ethical implications of their research are fundamental to them.’ These companies also tend to have more resources to undertake ethical reviews than academic labs, and can dedicate more full-time staff positions to training, broader impact mapping and research into the ethical implications of AI.

The use of AI-specific ethics principles and red lines

Many corporate companies like Meta, Google and Microsoft have published AI ethics principles that articulate particular considerations for their AI and data science research to consider, as well as ‘red line’ research areas they will not undertake. For example, in response to employee protests against a US Department of Defense contract, Google stated it will not pursue AI ‘weapons or other technologies whose principal purpose or implementation is to cause or directly facilitate injury to people’.[76] Similarly, DeepMind and Element AI have signed a pledge against AI research for lethal autonomous weapons alongside over 50 other companies; a pledge that only a handful of academic institutions have made.[77]

According to some participants, articulating these principles can make more salient the specific ethical concerns that researchers at corporate labs should consider with AI and data science research. However, other participants we spoke with noted that, in practice, there is a lack of internal and external transparency around how these principles are applied.

Many participants from academic institutions we spoke with noted they do not use ‘red line’ areas of research out of concern that these red lines may infringe on existing principles of academic openness.

Extent of reviews

Traditional REC reviews tend to focus on a single one-off assessment of research risk at the early stages of a project. In contrast, one corporate REC we spoke with described their review as being a continuous process in which a team may engage with the REC at different stages, such as when a team is collecting data prior to publication, and post-publication reviews into whether the outcomes and impacts they were concerned with came to fruition. This kind of continuous review enables a REC to capture risks as they emerge.

We note that it was unclear whether this practice was common among industry labs or reflected one lab’s particular practices. We also note that some academic labs, like the Alan Turing Institute, are implementing similar initiatives to engage researchers at various stages of the research lifecycle.

A related point flagged by some workshop participants was that industry ethics review boards may vary in terms of their power to affect product design or launch decisions. Some may make non-binding recommendations, and others can green light or halt projects, or return a project to a previous development stage with specific recommendations.[78]

Composition of board and external engagement

The corporate REC members we spoke with all described the composition of their boards as being interdisciplinary and reflecting a broad range of teams at the company. One REC, for example, noted that members of engineering, research, legal and operations teams sit on their ethical review committee to provide advice not only on specific projects, but also for entire research programmes. Another researcher we spoke with described how their organisation’s ethics review process provides resources for researchers, including a list of ‘banned’ publicly accessible datasets that have questionable consent and privacy issues but are commonly used by researchers in academia and other parts of industry.

However, none of the corporate RECs we spoke with had lay members or external experts on their boards. This raises a serious concern that perspectives of people impacted by these technologies are not reflected in ethical reviews of their research, and that what constitutes a risk or is considered a high-priority risk is left solely to the discretion of employees of the company. The lack of engagement with external experts or people affected by this research may mean that critical or non-obvious information about what constitutes a risk to some members of society may be missed. Some participants we spoke with also mentioned that corporate labs experience challenges engaging with external stakeholders and experts to consult on critical issues. Many large companies seek to hire this expertise in-house, bringing in interdisciplinary researchers with social science, economics and other backgrounds. However, engaging external experts can be challenging, given concerns around trade secrets, sharing sensitive data and tipping off rival companies about their work.

Many companies resort to asking participants to sign non-disclosure agreements (NDAs), which are legally binding contracts with severe financial sanctions and legal risks if confidential information is disclosed. These can last in perpetuity, and for many external stakeholders (particularly those from civil society or marginalised groups), signing these agreements can be a daunting risk. However, we did hear from other corporate REC members that they had successfully engaged with external experts in some instances to understand the holistic set of concerns around a research project. In one biomedical-based research project, a corporate REC claimed to have engaged over 25 experts in a range of backgrounds to determine potential risks their work might raise and what mitigations were at their disposal.

Ongoing training

Many corporate RECs we spoke with also place an emphasis on continued skills and training, including providing basic ‘ethical training’ for staff of all levels. One corporate REC member we spoke with noted several lessons learned from their experience running ethical reviews of AI and data science research:

- Executive buy-in and sponsorship: It is essential to have senior leaders in the organisation backing and supporting this work. Having a senior spokesperson also helped in communicating the importance of ethical consideration throughout the organisation.

- Culture: It can be challenging to create a culture where researchers feel incentivised to talk and think about the ethical implications of their work, particularly in the earliest stages. Having a collaborative company culture in which research is shared openly within the company, and a transparent process where researchers understand what an ethics review will involve, who is reviewing their work, and what will be expected of them can help address this concern. Training programmes for new and existing staff on the importance of ethical reviews and how to think reflexively helped staff level-set with what is expected of them.

- Diverse perspectives: Engaging diverse perspectives can result in more robust decision-making. This means engaging with external experts who represent interdisciplinary backgrounds, and may include hiring that expertise internally. This can also include experiential diversity, which incorporates perspectives of different lived experiences. It also involves considering one’s own positionality and biases, and being reflexive as to how one’s own biases and lived experiences can influence consideration for ethical issues.

- Early and regular engagement leads to more successful outcomes: Ethical issues can emerge at different stages of a research project’s lifecycle, particularly given quick-paced and shifting political and social dynamics outside the lab. Engaging in ethical reviews at the point of publication can be too late, and the earlier this work is engaged with the better. Regular engagement throughout the project lifecycle is the goal, along with post-mortem reviews of the impacts of research.

- Continuous learning: REC processes need to be continuously updated and improved, and it is essential to seek feedback on what is and isn’t working.

Other actors in the research ethics ecosystem

While academic and corporate RECs and researchers share the primary burden for assessing research ethics issues, there are other actors who share this responsibility to varying degrees, including funders, publishers and conference organisers.[79] Along with RECs, these other actors help establish research culture, which refers to ‘the behaviours, values, expectations, attitudes and norms of research communities’.[80] Research culture influences how research is done, who conducts research and who is rewarded for it.

Creating a healthy research culture is a responsibility shared by research institutions, conference organisers, journal editors, professional associations and other actors in the research ecosystem. This can include creating rewards and incentives for researchers to conduct their work according to a high ethical standard, and to reflect carefully on the broader societal impacts of their work. In this section, we examine in detail only three actors in this complex ecosystem.

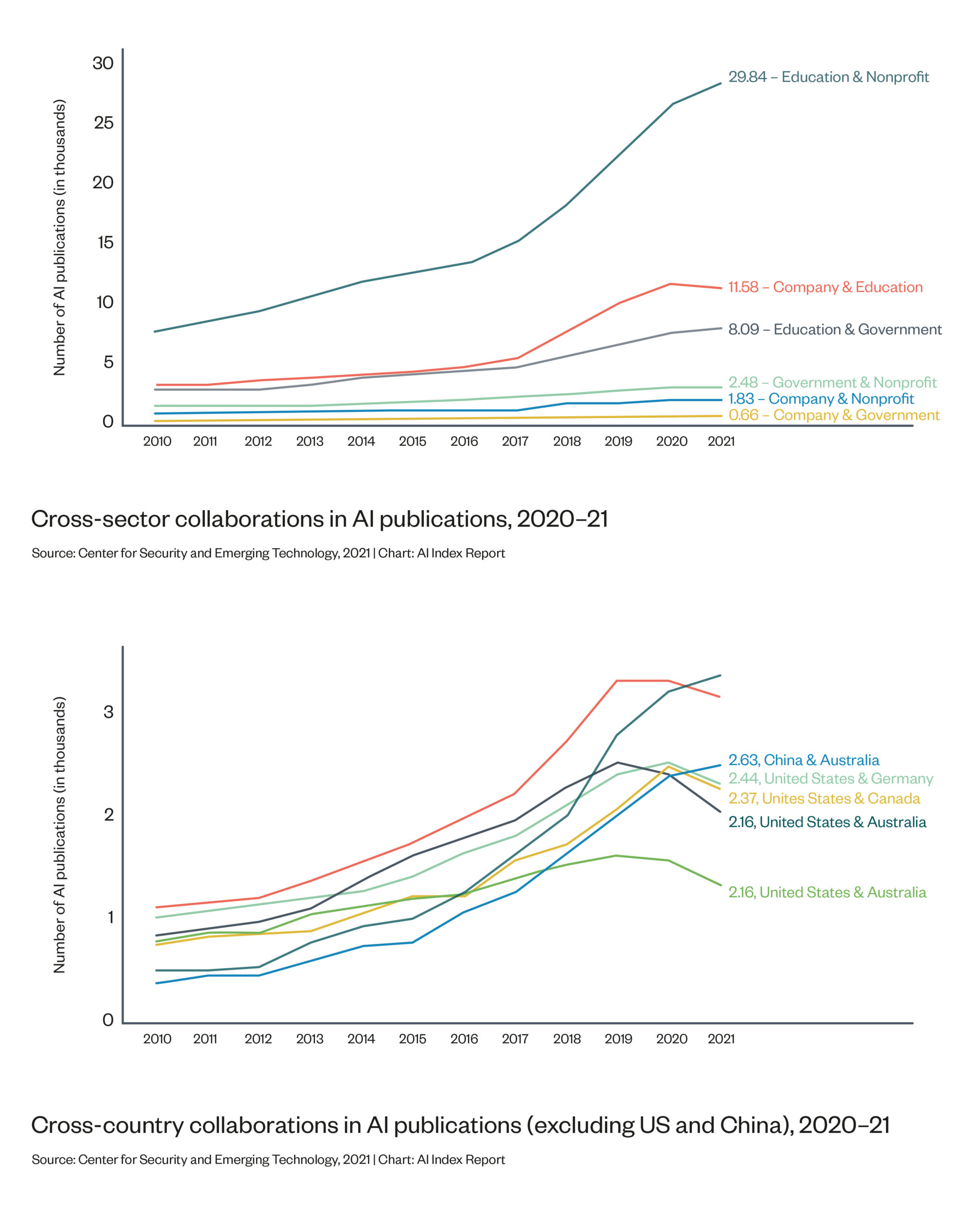

Figure 5: Different actors in the research ecosystem

This figure shows some of the different actors that comprise the AI and data science research ecosystem. These actors interact and set incentives for each other. For example, funders can set incentives for institutions and researchers to follow (such as meeting certain criteria as part of a research application). Similarly, publishers and conferences can set incentives for researchers to follow in order to be published.

Organisers of research conferences can set particular incentives for a healthy research culture. Research conferences are venues where research is rewarded and celebrated, enabling career advancement and growth opportunities. They are also forums where junior and senior researchers from the public and private sectors create professional networks and discuss field-wide benchmarks, milestones and norms of behaviour. As Ada’s recent paper with CIFAR on AI and machine learning (ML) conference organisers explores, there are a wide variety of steps that conferences can take to incentivise consideration for research ethics and broader societal impacts.[81]

For example, in 2020, the Conference on Neural Information Processing (NeurIPS) introduced a requirement that submitted papers include a broader societal impact statement of the benefits, limitations and risks of the research.[82] These impact statements were designed to encourage researchers submitting work to the conference to consider the risks their research might raise, and to conduct more interdisciplinary consultation with experts from other domains and engagement with people who may be affected by their research.[83] The introduction of this requirement was hotly contested by some researchers, who were concerned it was an overly burdensome ‘tick box’ exercise that would become pro-forma over time.[84] In 2021, NeurIPs shifted to adding ethical considerations into a checklist of requirements for submitted papers, rather than requiring a standalone statement for all papers to complete.

Editors of academic journals can set incentives for researchers to assess for and mitigate the ethical implications of their work. Having work published in an academic journal is primary goal for most academics, and a pathway for career advancement. Journals often put in place certain requirements for submissions to be accepted. For example, the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) has released guidelines on research integrity practices in scholarly publishing, which stipulate that journals should include policies on data sharing, reproducibility and ethical oversight.[85] This includes requirements that studies involving human subjects research must provide self-disclosure that a REC has approved the study.

Some organisations have suggested journal editors could go further towards encouraging researchers to consider questions of broader societal impacts. The Partnership on AI (PAI) published a range of recommendations for responsible publication practice in AI and ML research, which include calls for a change in research culture that normalises the discussion of downstream consequences of AI and ML research.[86]

Specifically for conferences and journals, PAI recommends expanding peer review criteria to include potential downstream consequences by asking submitting researchers to include a broader societal impact statement. Furthermore, PAI recommends establishing a separate review process to evaluate papers based on risk and downstream consequences, a process that may require a unique set of multidisciplinary experts to go beyond the scope of current journal review practices.[87]

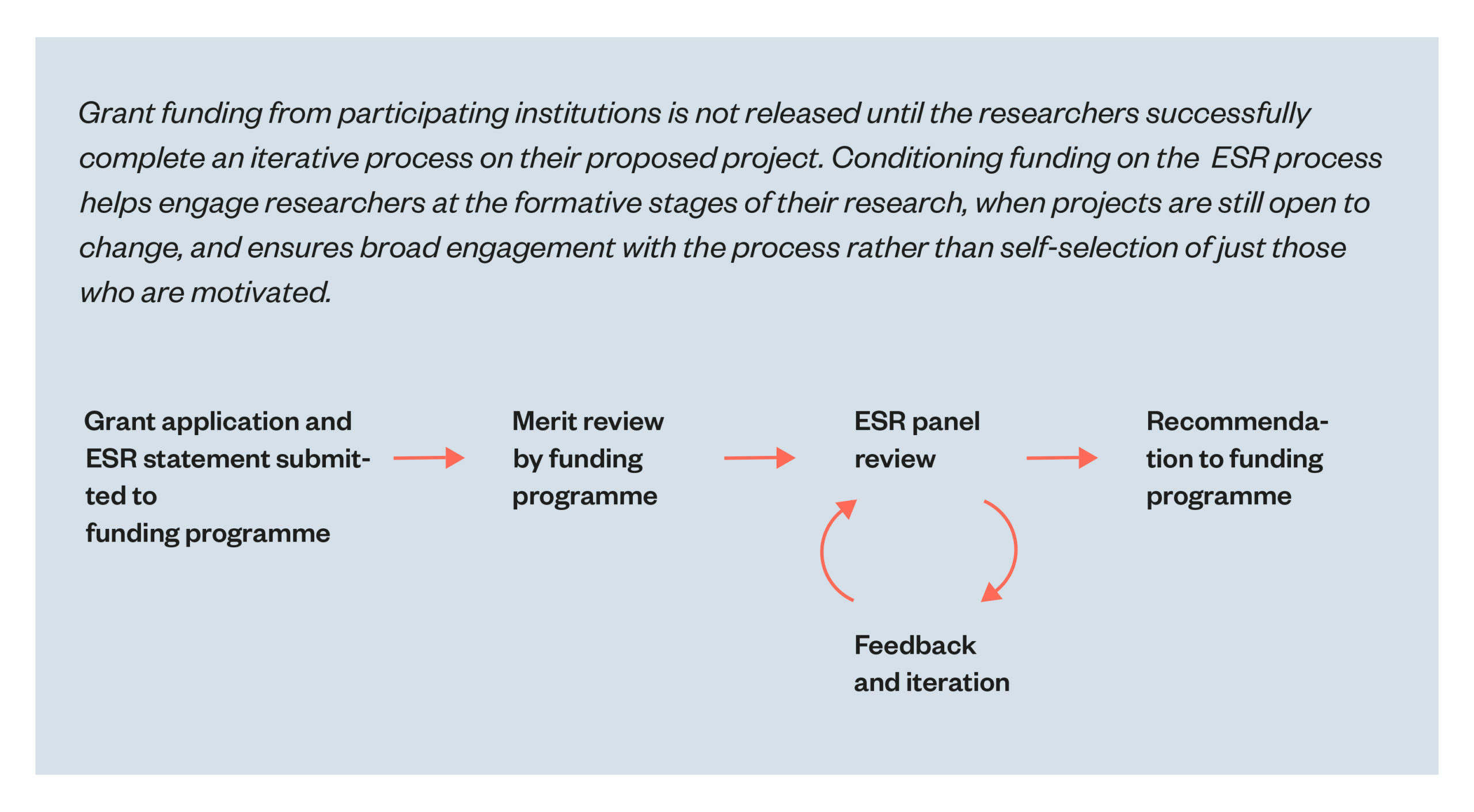

Public and private funders (such as research councils) can establish incentives for researchers to engage with questions of research ethics, integrity and broader societal impacts. Funders play a critical role in determining which research proposals will move forward, and what areas of research will be prioritised over others. This presents an opportunity for funders to encourage certain practices, such as requiring that any research that receives funding meets expectations around research integrity, Responsible Research and Innovation and research ethics. For example, Gardner recommends that grant funding and public tendering of AI systems should require a ‘Trustworthy AI Statement’ from researchers that includes an ex ante assessment of how the research will comply with the European HLEG’s Trustworthy AI standards.[88]

Challenges in AI research

In this chapter, we highlight six major challenges that Research Ethics Committees (RECs) face when evaluating AI and data science research, as uncovered during workshops conducted with members of RECs and researchers in May 2021.

Challenge 1: Many RECs lack the resources, expertise and training to appropriately address the risks that AI and data science pose

Inadequate review requirements

Some workshop participants highlighted that many projects that raise severe privacy and consent issues are not required to undergo research ethics review. For example, some RECs encourage researchers to adopt data minimisation and anonymisation practices and do not require a project to undergo ethics reviews if the data is anonymised after collection. However, research has shown that anonymised data can still be triangulated with other datasets to enable reidentification,[89] raising a privacy risk to data subjects and implications for the consideration of broader impacts.[90] Expert participants noted that it is hard to determine if data collected for a project is anonymous, and that RECs must have the right expertise to fully interrogate whether a research project has adequately addressed these challenges.

As Metcalf and Crawford have noted, data science is usually not considered a form of direct intervention in the body or life of individual human subjects and is, therefore, exempt from many research ethics review processes.[91] Similar challenges arise with AI research projects that rely on data collected from public sources, such as surveillance cameras or scraped from the public web, which are assumed to pose minimal risk to human subjects. Under most current research ethics guidelines, research projects using publicly available or pre-existing datasets collected and shared by other researchers are also not required to undergo research ethics review.[92]

Some of our workshop participants noted that researchers can view RECs as risk averse and overly concerned with procedural questions and reputation management. This reflects some findings from the literature. Samuel et al found that, while researchers perceive research ethics as procedural and centred on operational governance frameworks, societal ethics are perceived as less formal and more ‘fuzzy’, noting the absence of standards and regulations governing AI in relation to societal impact.[93]

Expertise and training

Another institutional challenge our workshop participants identified related to the training, composition and expertise of RECs. These concerns are not unique to reviews of AI and data science and reflect long-running concerns with how effectively RECs operate. In the USA, a 2011 study found that university research ethics review processes are perceived by researchers as inefficient, with review outcomes being viewed as inconsistent and often resulting in delays in the research process, particularly for multi-site trials.[94]

Other studies have found that researchers view RECs as overly bureaucratic and risk-averse bodies, and that REC practices and decisions can vary substantially across institutions.[95] These studies have found that that RECs have differing approaches to determining which projects require a full rather than expedited review, and often do not provide a justification or explanation for their assessments of the risk of certain research practices.[96] In some documented cases, researchers have gone so far as to abandon projects due to delays and inefficiencies of research ethics review processes.[97]

There is some evidence these issues are exacerbated in reviews of AI and data science research. Dove et al found systemic inefficiencies and substantive weaknesses in research ethics review processes, including:

- a lack of expertise in understanding the novel challenges emerging from data-intensive research

- a lack of consistency and reasoned decision-making of RECs

- a focus on ‘tick-box exercises’

- duplication of ethics reviews

- a lack of communication between RECs in multiple jurisdictions.[98]

One reason for variation in ethics review process outcomes is disagreement among REC members. This can be the case even when working with shared guidelines. For example, in the context of data acquired through social media for research purposes, REC members differ substantially in their assessment of whether consent is required, as well as the risks to research participants. In part, this difference of opinion can be linked to their level of experience in dealing with these issues.[99] Some researchers suggest that reviewers may benefit from more training and support resources on emerging research ethics issues, to ensure a more consistent approach to decision-making.[100]

A significant challenge arises from the lack of training – and, therefore, lack of expertise – of REC members.[101] While this has already been identified as a persistent issue with RECs generally,[102] AI and data science research can be applied to many disciplines. This means that REC members evaluating AI and data science research must have expertise across many fields. However, many RECs in this space frequently lack expertise across both (i) technical methods of AI and data science, and (ii) domain expertise from other relevant disciplines.[103]

Samuel et al found that some RECs that review AI and data science research are concerned with data governance issues, such as data privacy, which is perceived as not requiring AI-specific technical skills.[104] While RECs regularly draw on specialist advice through cross-departmental collaboration, workshop participants questioned whether resources to support examination of ethical issues relating to AI and data science research are made available for RECs.[105] RECs may need to consider which appropriate expertise is required for these reviews and how it will be sourced, for instance, via specialist ad-hoc advice, or the institution of sub-committees.[106]

The need for reviewers with expertise across disciplines, ethical expertise and cross-departmental collaboration is clear. Participants in our workshops questioned whether interdisciplinary expertise is sufficient to review AI and data science research projects, and whether experiential expertise (expertise on the subject matter gained through first-person involvement) is also necessary to provide a more holistic assessment of potential research risks. This could take the form of changing a REC’s composition to involve a broader range of stakeholders, such as community representatives or external organisations.

Resources

A final challenge that RECs face relates to their resourcing and the value given to their work. According to our workshop participants, RECs are generally under-resourced in terms of budget, staffing and rewarding of members. Many RECs rely on voluntary ‘pro bono’ labour of professors and other staff, with members managing competing commitments and an expanding volume of applications for ethics review.[107] Inadequate resources can result in further delays and have a negative impact on the quality of the reviews. Chadwick shows that RECs rely on the dedication of their members, who prioritise the research subjects, researchers, REC members and the institution ahead of personal gain.[108]

Several of our workshop participants noted reviewers do not have enough time to do a proper ethics review that evaluates the full range of potential ethical issues, or the right range of skills. According to several participants, sitting on a REC is often a ‘thankless’ task, which can make finding people willing to serve difficult. Those who are willing and have the required expertise risk being overloaded. Reviewing is ‘free labour’ with little or no recognition, and the question arises how to incentivise REC members. It was discussed that research ethics review should be budgeted appropriately to engage with stakeholders throughout the project lifecycle.

Challenge 2: Traditional research ethics principles are not well suited for AI research

In their evaluations of AI and data science research, RECs have traditionally relied on a set of legally mandated and self-regulatory ethics principles that largely stem from the biomedical sciences. These principles have shaped the way that modern research ethics is understood at research institutions, how RECs are constructed and the traditional scope of their remit.

Contemporary RECs draw on a long list of additional resources for AI and data science research in their reviews, including data science-specific guidelines like the Association of Internet Researchers ethical guidelines,[109] provisions of the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) to govern data protection issues, and increasingly the emerging field of ‘AI ethics’ principles. However, the application of these principles raises significant challenges for RECs.

Several of our expert participants noted these guidelines and principles are often not implemented consistently across different countries, scientific disciplines, or across different departments or teams within the same institution.[110] As prominent research guidelines were originally developed in the context of biomedical research, questions have been raised about their applicability to other disciplines, such as the social sciences, data science and computer science.[111] For example, some in the research community have questioned the extension of the Belmont principles to research in non-experimental settings due to differences in methodologies, the relationships between researchers and research subjects, different models and expectations of consent and different considerations for what constitutes potential harm and to whom.[112]

We draw attention to four main challenges in the application of traditional bioethics principles to ethics reviews of AI and data science research:

Autonomy, privacy and consent

One example of how biomedical principles can be poorly applied to AI and data science research relates to how they address questions of autonomy and consent. Many of these principles emphasise that ‘voluntary consent of the human subject is absolutely essential’ and should outweigh considerations for the potential societal benefit of the research.

Workshop participants highlighted consent and privacy issues as one of the most significant challenges RECs are currently facing in reviews of AI and data science research. This included questions about how to implement ‘ongoing consent’, whereby consent is given at various stages of the research process; whether informed consent may be considered forced consent when research subjects do not really understand the implications of the future use of their data; and whether it is practical to require consent be given more than once when working with large-scale data repositories. A primary concern flagged by workshop participants was whether RECs put too much weight on questions of consent and autonomy at the expense of wider ethical concerns.

Issues of consent largely stem from the ways these fields collect and use personal data,[113] which differs substantially from the traditional clinical experiment format. Part of the issue is the relatively distanced relationship between data scientist and research subject. Here, researchers can rely on data scraped from the web – such as social media posts; or collected via consumer devices – such as fitness trackers or smart speakers.[114] Once collected, many of these datasets can be made publicly accessible as ‘benchmark datasets’ for other researchers to test and train their models. The Flickr Faces HQ dataset, for example, contains 70,000 images of faces collected from a photo-sharing website and made publicly accessible with a Creative Commons license for other researchers to use.[115]

These collection and sharing practices pose novel risks to the privacy and identifiability of research subjects, and challenge traditional notions of informed consent from participants.[116] Once collected and shared, datasets may be re-used or re-shared for different purposes than those understood during the original consent process. It is often not feasible for researchers re-using the data to obtain informed consent in relation to the original research. In many cases, informed consent may not have been given in the first place.[117]

Not being able to obtain informed consent does not give the researcher a blank slate, and datasets that are continuously used as a benchmark for technology development risk normalising the avoidance of consent-seeking practices. Some benchmark datasets, such as the longitudinal Pima Indian Diabetes Dataset (PIDD), are tied to a colonial past of oppression and exploitation of indigenous peoples, and its use as a benchmark dataset perpetuates these politics in new forms.[118] The challenges to informed consent can cause significant damage to public trust in institutions and science. One notable example involved a Facebook (now Meta) study in 2014, in which researchers were able to monitor users’ emotional states and manipulated their news feed without their consent, showing more negative content to some users.[119] The study led to significant public concern, and raised questions about how Facebook users could give informed consent in instances where they lack control, let alone awareness of the study.

In some instances, AI and data science research may also pose novel privacy risks relating to the kinds of inferences that can be drawn from data. To take one example, researchers at Facebook (now Meta) developed an AI system to identify suicidal intent in user-generated content, which could be shared with law enforcement agencies to conduct wellness checks on identified users.[120] This kind of ‘emergent’ health data produced through interactions with software platforms or products is not subject to the same requirements or regulatory oversight as data from a mental health professional.[121] This highlights how an AI system can infer sensitive health information about an individual based on non-health related data in the public domain, which could pose severe risks for the privacy of vulnerable and marginalised communities.