Algorithmic impact assessment: user guide

This user guide is part of our wider work exploring algorithmic impact assessments (AIAs) in healthcare

8 February 2022

Reading time: 43 minutes

This user guide has been developed by the Ada Lovelace Institute as part of a research

partnership with the NHS AI Lab exploring algorithmic impact assessments (AIAs) in healthcare. See the project page to learn about our wider work exploring AIAs in healthcare, and to access the full report .

This user guide describes the recommended algorithmic impact assessment (AIA) process for teams seeking access to imaging data from the proposed National Medical Imaging Platform (NMIP), for one of three reasons:

- To conduct research that uses NMIP imaging data.

- To train a new medical product that uses NMIP imaging data.

- To test an existing medical product on NMIP imaging data.

It provides step-by-step guidance for project teams on how to conduct an algorithmic impact assessment (AIA) for their project. The completion of this assessment is required by the NHS AI Lab team to grant access to the NMIP dataset.

This user guide is supported by an template for the process.

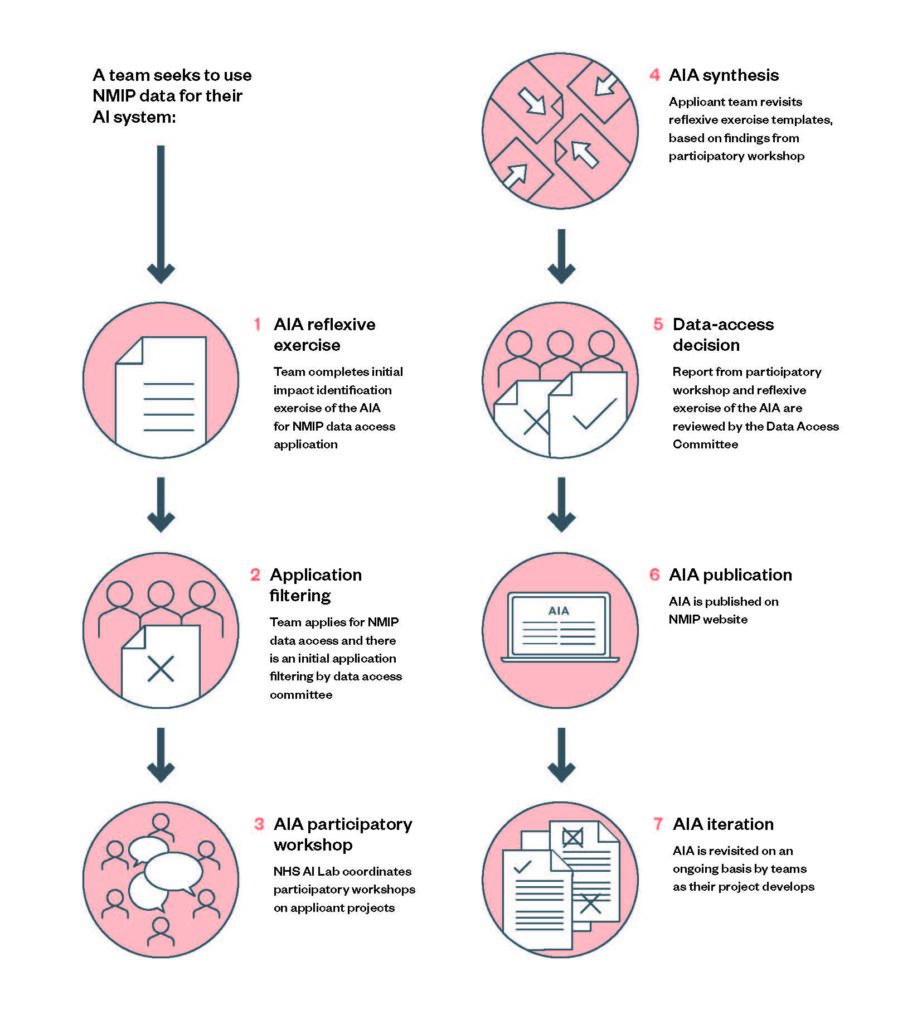

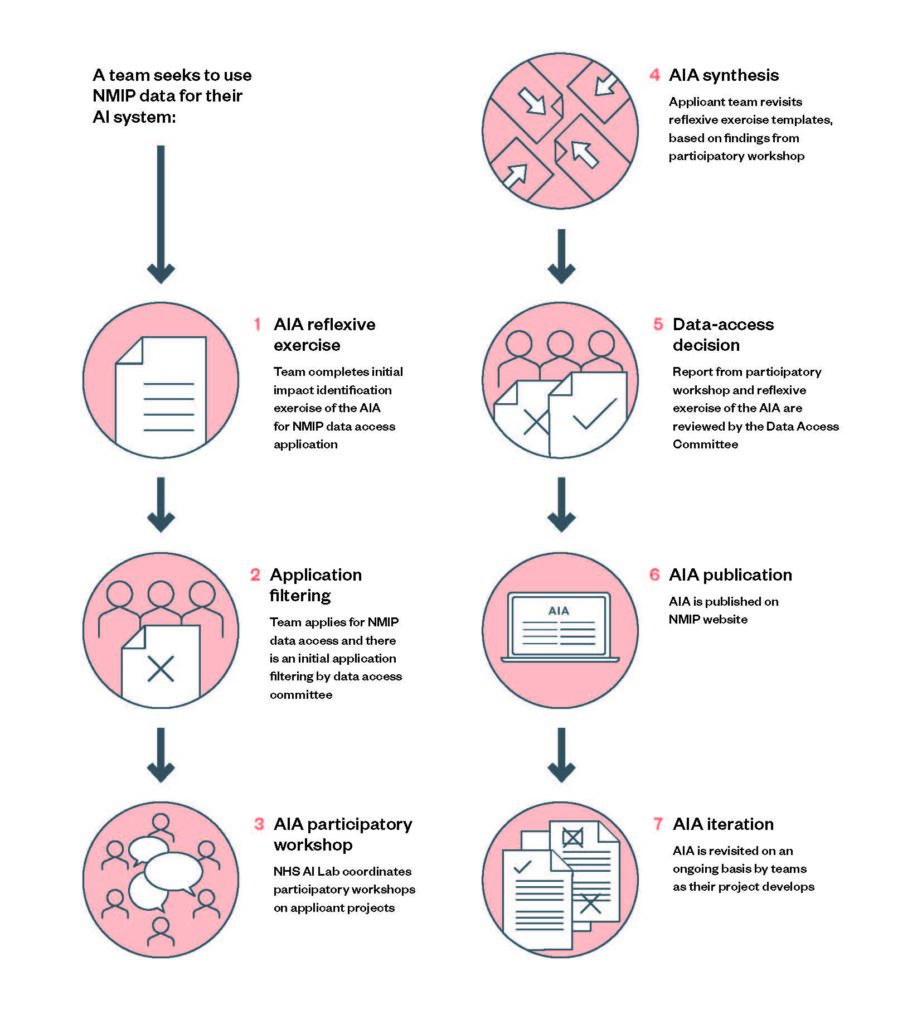

The AIA process at a glance

Purpose of this guide

This guide provides step-by-step guidance for project teams seeking access to imaging data from the National Medical Imaging Platform (NMIP). It outlines how to conduct an algorithmic impact assessment (AIA) for their project. The completion of this assessment is required by the NHS AI Lab team to grant access to the NMIP dataset. This is a sample version of this process guide, which is based on existing research, interviews and feedback with relevant experts and development teams using the NMIP. We expect this guidance to develop over time as teams trial the process and discover its strengths and limitations, and as the public and research community provide feedback on published AIAs completed by NMIP users.

This sample version of the process guide is based on research, interviews with and feedback from relevant experts and development teams who may be interested in NMIP access. For full details of the research, please see the full Ada Lovelace Institute report Algorithmic impact assessment: a case study in healthcare.1

What is an algorithmic impact assessment?

Algorithmic impact assessments (referred to throughout this report as ‘AIAs’) are a tool for assessing possible societal impacts of an algorithmic system before the system is in use (with ongoing monitoring often advised).2 They have been proposed by researchers, policymakers and developers as a way to create greater accountability for the design and deployment of AI systems,3 which can in turn build public trust in the use of these systems, mitigate their potential to cause harm to people and groups,4 and maximise their potential for benefit.5

Who is this guide for?

You are reading this guide because you or members of your team are seeking access to the NMIP dataset. You have probably designed, or are designing, a system, tool, model or product that would benefit from access to the NMIP data. Regardless of whether you are in the early or late stages of your project’s development, the AIA process will help your team consider the individual and societal impacts of your project, direct your thinking towards strengthening benefits and mitigating harms, and enable you to better communicate about anticipated impacts with affected communities.

This process document is aimed at researchers and private firms who are seeking

access to the NMIP for one of three reasons:

- To conduct research that uses NMIP imaging data.

- To train a new medical product that uses NMIP imaging data.

- To test an existing medical product on NMIP imaging data.

This guide will also advise on how to produce the documented evidence that you have undertaken these activities that is required for NMIP access. Some of this documentation will be published on the NMIP website once the AIA is completed, including evidence of reflexive impact identification activities and an understandable account of system details. This guide provides advice on how to implement plain-language summaries and explanations of your system.6

This guide should be read and implemented by both:

- designers, developers, data scientists and product or research managers working on the system/tool/model or product that intends to build on NMIP imaging data

- wider members of the project team not involved in development but involved in key decision-making. These roles will vary depending on organisational context, but could include policy, legal or executive officers, project managers, or those working in public participation in health.

This process has been developed specifically for the context of the NMIP and is tailored to these specific requirements. We anticipate the exercises will be useful, with some amendments, in other contexts, with accompanying changes to the accountability mechanism to operate in a different set of conditions. For further detail on the design and rationale of this process, see the full Ada Lovelace Institute report Algorithmic impact assessment: a case study in healthcare.7

Background

Purpose of the NMIP AIA Process

The NMIP AIA process is designed with the safety and care of patients and affected communities in mind, to help NMIP applicant teams think through reflexively the potential impacts of projects on people, society and the environment. It consists of a team activity and exercises with wider stakeholders to produce an output document for the NMIP Data Access Committee (DAC) to review as part of your application.

This structured exercise can help your team mitigate potential risks and maximise potential benefits from your system or product, while also documenting key decisions, values and choices. It helps you think of impacts beyond, for example, individual data privacy, or quality and safety – covered comprehensively in existing healthcare regulation and governance

– to broader societal impacts, such as whether this technology may disproportionately affect some patients, or how it may be unintentionally or intentionally misused to cause harm.

To support this, the NMIP AIA process includes a dedicated public and patient engagement exercise: a participatory workshop that is designed to broaden the range of voices and perspectives included, to deliberate on harms and benefits of AI and data-driven systems.

At the end of the AIA process, you will have a completed template for the NMIP Data Access Committee to review as part of your application. This AIA template8 may be published on the NMIP website, to enable greater public accountability over the use of patient data to create medical technologies, now and in the future.

The goals of this AIA process are as follows:

- Accountability: creating accountable relationships between developers and individuals affected by their systems. The AIA process equips a forum of clinicians, a Data Access Committee (DAC), and patients with agency to request information needed to pass judgement on the system and its possible benefits and harms.

- Reflection/reflexivity: prompted reflection and critical dialogue on how the design and development of your system might result in particular harms and benefits.

- Standardisation: this AIA uses a clear format and consistent record-keeping to aid viewing and scrutiny, and to produce reflexivity. This also allows for internal consensus and standardisation on the guiding values, institutional expectations, etc.

- Independent scrutiny: providing external stakeholders, including the DAC and panellists in the participatory workshop with the powers to scrutinise, assess and evaluate AIAs.

- Transparency: disclosure of process details for internal and external visibility and further accountability with stakeholders including regulators, civil society, users, etc. provides as an output a stable record of the AIA process, for external and internal viewing now and in the future.

In order to achieve these goals, the AIA process and output make use of several strategies, the main approaches being that of documentation and participation:

- Documentation is the primary mechanism through which we accomplish these goals. Documentation can impact internal behaviours, produce crucial records and enable communication between otherwise alienated stakeholders.9 There are various effects of introducing documentation, including encouraging reflexive practice within teams by necessitating new kinds of thinking, changing internal documentation practice and recordkeeping, and enabling common language between internal stakeholders.

- Participation is another mechanism to introduce external perspectives to scrutinise the system and identify impacts outside the scope of awareness or concern for internal stakeholders. Participation enables external scrutiny and new perspectives not traditionally heard in the development and assessment of AI systems, as well as offering an independent view, outside certain internal priorities, to help build accountability.

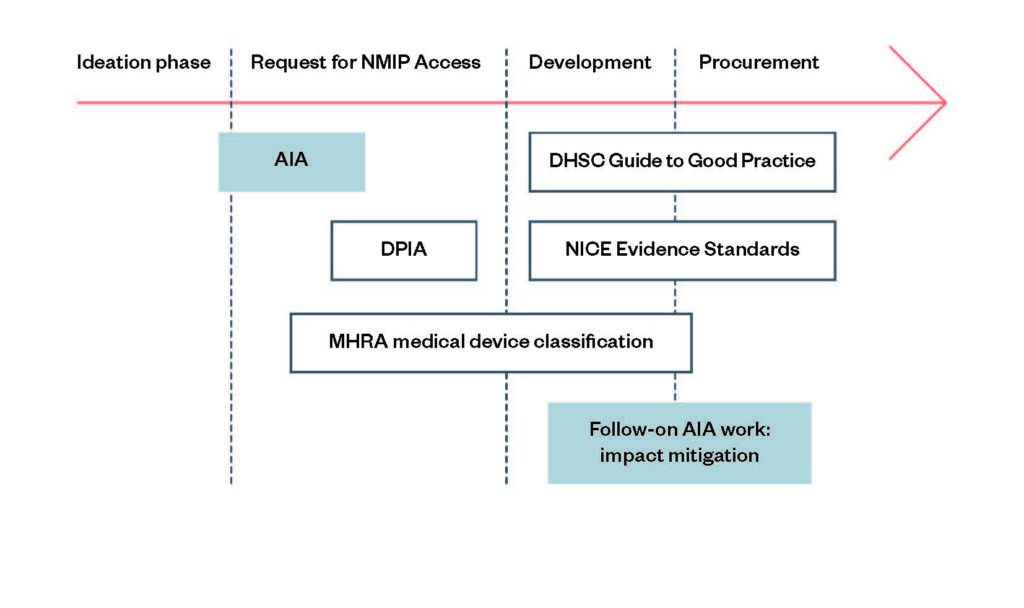

AIAs and existing complementary processes

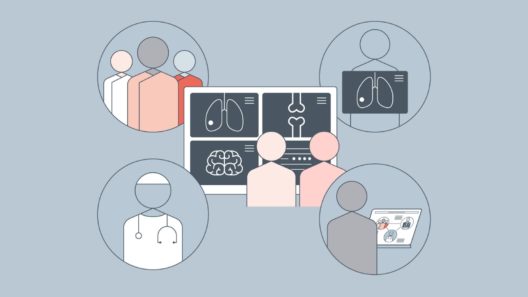

The NMIP AIA is designed specifically for the NMIP use case, to operate alongside existing processes in the health technology development cycle. An example of how an AIA might fit alongside other processes in the research and development pipeline is shown below:

Where does the AIA process fit?

The AIA process supports efforts to hold AI and healthcare systems accountable and build trustworthiness for the public, complementing existing mechanisms in the UK’s ecosystem of medical AI and data regulation.10 The AIA process also draws inspiration from existing algorithm accountability mechanisms in use elsewhere, such as algorithm audits and transparency mechanisms, other forms of impact assessment and public participation in healthcare initiatives.11

The AIA is not a silver bullet mechanism for holding AI systems accountable, nor is it a replacement to other initiatives like the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) medical device risk classification, other risk management frameworks, or Data Protection Impact Assessments (DPIAs), which are also a requirement of access to the NMIP. Rather, the AIA process complements these existing mechanisms, seeking to avoid duplication and being useful to inform other regulatory processes. It therefore focuses on addressing specific gaps identified through research – namely:

- public participation processes in healthcare AI

- narrow matrices of risk and impact that don’t cover, e.g. societal impact

- a lack of standardised methods to documenting AIA process and outputs and communicating this transparently and publicly. Developers and researchers should still follow existing best-practice standards and regulation for quality assurance and safety.

See the full Ada Lovelace Institute report Algorithmic impact assessment: a case

study in healthcare7 for further information on how this AIA complements existing processes in the ecosystem.

How to do an AIA

In this section, we present the process and outputs required to be completed as part of the AIA – what gets done, who does it, the purpose, the timeframe, and resources required, and what needs to be produced at the end.

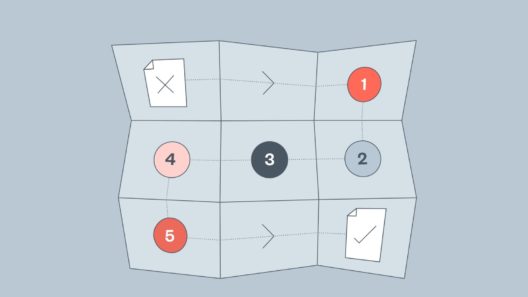

There are seven steps in the AIA process, of which four involve participation of the

applicant team:

- Reflexive exercise: team conducts a reflexive exercise, completing the AIA

template - Participatory workshop: NHS AI Lab coordinates participatory workshops on

applicant projects - Synthesis: applicant team revisits the AIA template completed in the reflexive

exercise, based on findings from the participatory workshop

And later, once the AIA is complete, and the data-access decision has been reached:

- Iteration: AIA is revisited on an ongoing basis by teams as their project develops

Your AIA will be led by:

- Your project team, comprising tech developers, principal investigator/project

manager

Your AIA is deliberated on by:

- The NMIP Data Access Committee (DAC)

- The participants in the participatory workshop

Your AIA is assessed by:

- The NMIP Data Access Committee (DAC)

Step 1: Reflexive exercise

The AIA process begins before applying for access to the NMIP: the reflexive exercise is completed by your team to help you identify possible harms and impacts arising from your project, the affected stakeholders, and some ethical considerations common to AI in healthcare. This thinking is captured in the AIA template, alongside some high-level project information.

Step 2: Application to NMIP

You will submit the AIA template completed in the reflexive exercise to the NMIP Data Access Committee (DAC) as part of the NMIP application initial filtering process. Those who have completed the AIA, and meet the DAC screening criteria will proceed to step 3.

Step 3: Participatory workshop

The NHS AI Lab coordinates participatory workshops on applicant projects (one project per workshop). The workshop gathers patients and the public to discuss your project and its potential impacts. This is an opportunity to widen the range of perspectives informing the AIA, and for members of your team to hear the views of participants.

An NHS-appointed rapporteur is present at the workshop to provide an additional report of the workshop to submit to the DAC as evidence to inform the final access decision.

Step 4: Synthesis

After the participatory workshop, you will return to the AIA template and update it based on what you have heard and learned. You may wish to reconvene team members involved in the initial completion of the reflexive exercise to discuss and review this.

Step 5: Data-access decision

The updated AIA template is then submitted to the NMIP Data Access Committee (DAC), as well as the rapporteur’s summary of the participatory workshop. The DAC will assess the strength and quality of the AIA, as well as reviewing other material required as part of the NMIP application in order to decide whether to grant access to NMIP imaging data.

Step 6: Publication

The completed AIA is published on a central NHS repository, alongside a contact point for your team to field any questions about the AIA. Only successful AIAs will be published, though applicants have the option of publishing the AIA for their project regardless of NMIP access decision, to share what they have learned.

Step 7: Iteration

The AIA is revised regularly to ensure an iterative approach to impact assessment. Trigger points for iteration include a revisitation after a two-year fixed time period, for possible new team members to be introduced to the process and for further reflection. The DAC may also have suggestions for revisitation in certain cases at their discretion. If the proposed system changes course significantly, such as a product function, scope or application change, or a change in user base, the AIA should be revisited.

Exercises

Reflexive exercise

Overview

The aim of this exercise is to help your team identify potential real-world impacts on people and society from this project. This encourages a reflexive assessment on who the affected communities of your AI system are: are there particular subpopulations that might interact differently with your product, and which people or groups might be harmed when the system fails? It also provides space for your team to discuss some common ethical considerations arising from adoption of AI systems in the healthcare space, and decide which will have a bearing on your system, research or model.

By considering the best and worst scenarios of your project’s application, this process will help you identify possible outcomes of your project, the conditions or resources necessary for you to achieve your best-case scenario, and possible hurdles you might meet on the way to this point. Your team will consider which of the scenarios are likely to cause harm, to which stakeholders, and how. You will prioritise harms in relation to the perceived importance, urgency, difficulty and detectability of the harms by your team and consider ways these harms might be mitigated.

The reflexive exercise is an internally run, first attempt at impact identification, which will be submitted as part of the initial application to the NMIP. If your team passes the initial application filtering, the impacts identified and knowledge produced during the reflexive exercise will inform the participatory workshop, which is conducted with a panel of patient and public representatives who will discuss and deliberate on your project.

Your team will document the findings of the reflexive exercise in the AIA template.13

The template consists of a series of question-and-answer prompts to support you through the process. The template also asks for a brief record of high-level project purpose and the intended uses of your system, model or research, providing additional context for the Data Access Committee who will review your template, and the public when the template is published.

Outputs

First attempt at impact identification and analysis, recorded in the AIA template.

When to complete

This exercise should be started once a project team makes the decision to apply for NMIP access.

Step-by-step process

- Project teams should first identify the lead for this exercise (we recommend the project team lead, principal investigator, or product lead) and a notetaker.

- The lead should organise and facilitate a 2–3 hour meeting with all relevant team members to work through the prompts in the AIA template.

- The notetaker will be responsible for writing up the team’s answers in the template document, which may take another 1–2 hours.

We estimate the reflexive exercise will take 3–5 hours in total (including writing up).

How to work through the template

Follow the prompts in chronological order

The prompts are designed to emulate existing AIA methodologies to identify impacts, such as the Canadian AlA online tool, that follow a question-and-answer format. The prompts are set out into four sections: high-level project information; common ethical considerations; impact identification & scenarios; and potential harms analysis.

- High-level project information asks teams to describe the project and its intended use. If your organisation has a mission statement, there is space to list this here, with links to website material if appropriate, before details on your project team/organisation and the inputs and outputs of this system, model or research. This section asks for details on the affected stakeholders that will interact with this system, for which we urge teams to be as specific as possible: nurses, hospital administration staff, patients of a particular kind, etc.

- Common ethical considerations: this section guides you through common

ethical considerations that occur in the context of healthcare and AI, such as:- Data sharing and privacy issues (looking forward to potential uses of the system, as opposed to current data processing).

- Surveillance, nudging and paternalism, consent and autonomy.

- Transformational effects in the ecosystem context, such as profiling,

discrimination and deskilling of workforce. This section also asks for details on how the system might be unintentionally misused, such as failures in staff training and support, scope creep, a failure to comply with healthcare regulation, or possible environmental impacts.

- Impact identification and scenarios ask teams to consider the possible benefits and harms that could occur when this project is being used by different stakeholders in a) the best-case scenario and b) the worst-case scenario, and for this scenario, both when the project is working as designed or as intended, and when it’s not working in some way or has failed. This section requires details of the kind of socio-environmental conditions that are necessary for this system to operate successfully: how stakeholders would optimally interact, what information would be shared, what workflow dependencies need to exist, as well as what infrastructure is required. It also asks what are likely challenges or hurdles to achieving the best-case scenario.

- Potential harm analysis: this final section asks applicant teams to list the potential harms to different stakeholders that arise across all scenarios surfaced previously. It asks teams to make an assessment on the perceived importance, urgency, difficulty and detectability of each harm, and a potential mitigation plan for these harms. This exercise helps teams consider how harms might be distributed, and helps teams put in place design decisions that would mitigate these harms.

You can read the question prompts and tips for the reflexive exercise in the AIA template.14

What happens once the exercise is complete

Once applicant teams have completed the exercise, they should submit their application to the NMIP.

Participatory workshop

Overview

After the internal exercise is completed and NMIP application submitted, the applicant project team takes part in the participatory workshop.

In the participatory workshop a panel comprising of patients and members of the public who – guided by NHS AI Lab facilitators and independent experts – meet and deliberate on the potential impacts arising from this system.

The workshop broadens participation in the impact assessment process and is tailored toward the NMIP applicant’s use case. It follows best practice public engagement methods. It offers a way for impact assessment to be scrutinised by patients and the public, increasing accountability and transparency. It may also identify findings that improve the AI product or model, helping teams better achieve their aims.

Output

Project teams participating in the participatory workshop should make their own notes in the workshops, to feed into the impact identification & analysis sections of the template.

An NHS AI Lab rapporteur will also make independent notes which will be reviewed and checked by the workshop participants, and shared with the NMIP Data Access Committee.

See Appendix B: Participatory workshops for a detailed outline of how the participatory workshops will be conducted by the NHS AI Lab.

Data-access decision

After completing the reflexive exercise and participatory workshop, synthesising the findings, and including the additional AIA process and model detail in the template, you will receive a data-access decision.

After the Data Access Committee (DAC) renders their decision, the project team may choose to incorporate additional answers in the AIA template document that respond to any concerns, challenges, or considerations raised by the DAC. Project teams will have two weeks to complete this exercise before the AIA document is published.

Publication of the AIA

The final part of the AIA process will involve the publication of the completed AIA on the NMIP website. On the DAC’s decision, the AIAs of will be published within a fixed time period on the NMIP website. Only successful applications – those who have undertaken both the reflexive exercise and the participatory workshop, and have been granted access to the dataset – will be required to be published, though the DAC may publish (anonymised) high-level observations about unsuccessful applications periodically as a learning opportunity.

Ongoing AIA process

Depending on the potential impacts identified, the Data Access Committee may choose to require project teams to revisit the AIA at a set future time. Even if the DAC does not mandate this, we encourage project teams to undertake this review exercise to reflect developments in the system. For instance, if there is a significant shift in scope or application or a notable change in the dataset, a team should review the AIA template and may want to update the published AIA as a result. It may also support the embedding of data ethics practice in your team to review the AIA template at a set period, such as annually.

Further resources

This AIA process offers a means to pre-emptively assess possible social impacts of a model prior to its deployment, which results in the creation of the AIA document – a single artefact.

As discussed above, the AIA should not be understood as an end-to-end solution for governing AI systems: it does not include guidance for completing other regulatory initiatives or project management activities, as we consider these out of scope of an AIA.

We supply here resources for pre- and post-work activity that support and complement the AIA process.

Pre-AIA

Alan Turing Institute’s stakeholder impact assessment

The Turing’s stakeholder impact assessment (SIA) focuses on helping public-sector departments identify a wide range of relevant stakeholders, to help unforeseen risks that may impact on individuals and the public good.15

The SIA in this report sets out certain activities to be taken place at the ‘alpha phase’ (problem formulation), which includes ‘identifying affected stakeholders’: applicants may find it helpful to use this as a guide to identify affected individuals and communities very early on in the process, and in order to be clear on how different interests might coalesce in this project – a useful precursor for completing the reflexive exercise in this AIA.

‘Closing the AI Accountability Gap’ end-to-end framework for internal algorithmic auditing

Accompanying their paper on ‘Closing the AI Accountability Gap’,16 researchers have created document templates for teams conducting internal algorithmic auditing – a targeted approach focusing on assessing a system for potential biases.17 The templates for the mapping and scoping phases are transferrable to this context. These exercises provide a means to boost reflexivity and clearly establish values and principles early in the project processes.18 These resources include an example AI principles statement and an example stakeholder map.

You can find these templates on Google Drive.

Post-AIA

Model cards template

Once technical attributes have been ironed out, and you are ready to deploy your model, we recommend your developers consider completing a model card template – a mechanism developed by Google researchers to encourage transparent model reporting.19 External scrutiny, transparency and accountability are strengthened by adopting this approach, as a model card provides a standardised record of technical system attributes, and a publicly available model card also provides regulators and downstream users of your model with insight into how it works.

You can see example model cards from Google.

Appendix A: Glossary of terms

This glossary provides definitions of key terms that appear in this guide, and how we use them (which may differ from other applications of terms elsewhere).

AI / Artificial intelligence

Artificial intelligence (AI) refers to systems that display intelligent behaviour by

analysing their environment and taking actions – with some degree of autonomy –

to achieve specific goals.20

AI system

AI-based systems can be purely software-based, acting in the virtual world (e.g. voice assistants, image-analysis software, search engines, speech and face-recognition systems) or can be embedded in hardware devices (e.g. advanced robots, autonomous cars, drones or Internet of Things applications). Many AI systems are made up of algorithms, which are a series of computational steps that enable certain inputs to be turned into new outputs. A metaphor for an algorithm is a cooking recipe, which provides steps for turning inputs (your ingredients) into an output (the completed dish).

For the purposes of this report, we refer to an AI system as a sociotechnical system, which may be made up of one or several algorithms. AI systems use automated reasoning to aid, replace or augment human decision-making.

Algorithmic impact assessment (AIA)

Algorithmic impact assessments are a mechanism for enabling greater accountability of an algorithm by assessing the possible societal impacts of an algorithmic system before the system is in use (with ongoing monitoring often advised). AIAs draw from a long history of impact assessments in other domains that seek to inform policymakers and executives by predicting and evaluating the potential economic, social and environmental impacts of a proposed policy or product.21

Bias

Bias can take on several different meanings in different contexts. In this guide, we primarily refer to ‘algorithmic bias’ as the ways in which AI and AI systems systematically and unfairly discriminate against certain people or certain groups.22 This bias results in different types of harm: harms of allocation, where a system allocates or withholds from certain groups an opportunity like a job, or a resource like a loan; and harms of representation, where systems discriminate and subordinate along the lines of identity.23 Bias can occur in different parts of the AI lifecycle – sampling bias, for example, can occur when collecting data, whereas automation bias can occur when a system that is deployed exacerbates existing human decision-making biases.24

Harms

Harms are lived experiences of the adverse consequences of a system’s deployment and operation in the real world. Some of these harms can be anticipated and avoided through impact assessments as potential impacts, others cannot be foreseen. Redress procedures must be developed to address any unanticipated harms to secure justice for those affected.

Impact

An ‘impact’ in an impact assessment refers to a measurable effect, outcome or influence arising from a particular intervention, of which may be beneficial, neutral or harmful. Scholarship from Data & Society considers that ‘impact’ in impact assessment for technology is a conceptual construct designed to act as a proxy or stand-in for the potential influence of a technology on the lived experience of different stakeholders – including harms or benefits – in order to make this influence measurable.25

NMIP AIA

In this guide, we refer to the algorithmic impact assessment process presented in this guidebook as ‘the AIA’, which also includes the templated output that the AIA process demands. We emphasise that AIAs are context-specific – there are many different approaches to AIAs and no one single ‘golden’ approach.

The process and outputs laid out here are in reference to the use of AIAs for the purposes of ensuring greater accountability over AI systems that use NMIP data – this will probably need to be amended to be applicable to other use cases.

We distinguish between the AIA process – what gets done in an AIA, who’s involved, the time, the resources required – and the AIA output – documents and artefacts produced from the process. Both process and outputs are integral elements of our AIA.

Model, system, tool or product?

This guide predominately uses ‘system’ to refer to the AI systems intended to be built on imaging data. Recognising the likely breadth and diversity of projects applying to the NMIP, teams may wish to use their own preferred technology for the AIA exercises. For example, ‘system’ may not be appropriate for teams not intending to build a specific system, and those teams may prefer to use ‘research’ when referring to the intended use of NMIP data. but teams can use their own preferred terminology.

Sociotechnical

A sociotechnical system, or sociotechnical approach, refers to the interrelation of social and technical factors, systems and principles that lead to the production and use of a product. Sociotechnical elements could span physical infrastructure, like software and hardware, but also social and cultural factors and motivations.

The example of a car is helpful: a car consists of an engine, computer system, steel frame, interior fittings, but once on the road, the person responsible for the car is required to observe social factors including road laws, road infrastructure and norms of driving.

Reflexivity

Adopting reflexivity – or behaving reflexively – means examining and responding to one’s (or that of a team’s) own practices, motives and beliefs during a research process. Reflexivity is an essential principle for completing a thorough, meaningful and critical AIA.

Risk

We use risk to mean the uncertainty of outcome of a given event, where a risk is generally considered to create negative outcomes. Conducting a risk assessment offers a means to both pre-emptively identify risks, and consider ways to mitigate or monitor these risks. In the data and AI regulatory space, many initiatives categorise risk around individual losses – for example, Data Protection Impact Assessments (DPIAs) are framed around identifying risks to individual data privacy.

User

References to the ‘user’ refers to the person who is intended to using the AI system once deployed in its clinical setting, unless otherwise stated. This may be a radiologist reading the system’s diagnosis suggestion, or the patient themselves for a patient-facing system, or – in many cases – both clinicians and patients. It is important to note here that ‘user’ does not capture every possible stakeholder who may be involved with the development and use of an AI system: for example, a hospital administrator could have a part to play in implementing the system into its clinical setting, but may not a designated ‘user’. The AIA template provides further guidance on how to identify and address the needs of both users and other stakeholders in this AIA process.

Appendix B: Participatory workshops

The NHS AI Lab will facilitate a participatory impact identification workshop in which members of the public will discuss potential impacts of your project.

The workshop will be made up of 8 – 12 people from a panel who reflect the diversity of the population that might be affected by the algorithm across: age, gender, region, ethnic background, socio-economic background, health condition or access to care. The panel may not be statistically representative of the UK public, but instead should reflect the diversity of perspectives and experiences in the populations/communities likely to be affected by the algorithms. Panel members will be remunerated for their involvement on the panel, and will go through an induction process to give them background on the NMIP, AI in healthcare and AIAs.

The applicant team will be involved in three ways:

- Presenting at the workshop to explain your project.

- Attending the workshop to be on hand to take questions and listen to participants.

- Updating your AIA as a result of what you have learnt in the workshop and impact mitigations you may consider.

Outline of the participatory workshop (run by NHS AI Lab)

Participants:

- 8 – 12 panel members to participate in the workshop and share their perspectives on the algorithm’s potential impacts.

- 1 or 2 facilitators to guide discussions, ensure participants views are listened to. Facilitators might be an NHS AI Lab staff member, user researcher from the applicant organisation or a consultant. They will have facilitation experience and be impartial.

- 1 or 2 technology developer representatives to represent the development team from the applicant organisation, who can explain the algorithm, take questions and, crucially, listen to the participants and take notes.

- 1 ‘critical friend’: a tech and society (T&S) professional to help answer participants’ questions and support participants to fully explore potential impacts. They are not intended to be deeply critical of the algorithm, but impartially support the participants in their enquiry.

- Ideally, there would also be a clinical ‘critical friend’, playing a similar role to the T&S professional.

Structure:

- 3 hour workshop, virtual or in person (for either format, ensure participants have support and access to engage fully).

Example agenda:

- Introduction to each other and the session, with a reminder of the purpose and agenda. (10 minutes)

- Presentation (20 minutes) from the tech developers about their algorithm in plain English, covering:

- Who their organisation is, its aims, values and whether it is for- or non-profit,

if it already works with the NHS and how. - What their proposed algorithm is: what it aims to do (and what prompted the need for the algorithm), how it works (not in technical detail), what data will be inputted (both how the algorithm uses NMIP data and the other datasets used to train, if applicable), what outputs the algorithm will generate, how the algorithm will be deployed and used (e.g. in hospitals, via a direct-to-patient app, etc.), who it will affect, what benefits it will bring, what impact considerations the team have already considered.

- Who their organisation is, its aims, values and whether it is for- or non-profit,

- Q&A led by the lead facilitator. (20 minutes)

- A session to identify potential impacts (45–60 minutes, with a break part way

through):- As one group or in two breakout groups, participants consider the algorithm and generate ideas for how it could create impacts. With reference to the best, worst and most likely scenarios that might arise from deployment that applicant teams completed for the reflexive exercise, participants will discuss these answers and provide their thoughts. Technology developer observes but does not participate unless the facilitator brings them in to address a technical or factual point. Critical friend observes and supports as required (guided by facilitator).

- This task should be guided by the facilitator, asking questions to prompt discussion on the scenarions, such as:

- What groups or individuals would be affected by this project?

- What potential risks, biases or harms do you foresee occurring for

use/deployment of this algorithm? - Who will benefit most from this project and how?

- Who could be harmed if this system fails?

- What benefits will this project have for patients and the NHS?

- What solutions or measures would they like to see adopted to

reduce the risks of harm?

Feeding results of participatory workshop back into the AIA (NMIP applicant

project teams)

After the participatory workshop is completed, NMIP applicant project teams should spend time revisiting the template completed in the reflexive exercise to update any answers in the AIA document based on the feedback from the workshop participants.

NHS AI Lab rapporteur prepares report on workshop

Separately, the NHS AI Lab rapporteur in the workshops will prepare a report on the findings from the panel to share independently with the Data Access Committee (DAC). The DAC may use this report to ask questions of project leads during data-access decisions.

Approximate time

Approximate total: 15 hours, most of which will be run by NHS AI Lab. Total time for NMIP applicant project teams will be around 6 hours.

- 1 x 2 hour induction session (to inform the panel)

- 1 x 3 hour impact identification workshop

- 2 hours for rapporteur to collate findings

- 1–3 hours for teams to update the impact identification template after the exercise

- 4 hours for NHS to build addendum with additional evidence from the exercise, to give to DAC once the updated AIA has been submitted

- 4 hours of asynchronous panel review of updates

- Additional hours to recruit, organise workshop resources

For fuller detail on panel recruitment, and workshop organisation, please see the full Ada Lovelace Institute report Algorithmic impact assessment: a case study in healthcare, Appendix 4.1

Appendix C: Research partnership with NHS AI Lab

This process document stems from a research project the Ada Lovelace Institute has conducted with the National Health Service thanks to a £66,000 grant from the Department of Health and Social Care. Building on Ada’s existing work on assessing algorithmic systems, the core objective of this project is to evaluate the literature on AIA methods and create a bespoke AIA process for the NHS AI Lab to implement for their specific use case – where technology developers seeking access to a database of national medical images must complete an AIA in order to be granted access to the dataset.

Existing implementation has tended to focus on either public-sector procurers of systems (such as the Canadian AIA),27 or the developers of new technology themselves (such as use of human rights impact assessments in industry.28

The National Medical Imaging Platform provides a novel case study for AIA methodologies as it sits at the intersection of two subjects of impact assessment: private-sector developers and the public sector. This exploratory study therefore offers a new lens through which to examine and develop algorithmic impact assessment.

In this project, the Ada Lovelace Institute followed three research questions:

- As an emerging methodology, what does an AIA process involve, and what can

it achieve? - What is the current state of thinking around AIAs and their potential to produce accountability, minimise harmful impacts, and serve as a tool for the more equitable design of AI systems?

- How could algorithmic impact assessments be conducted in a way that is effective, inclusive and trustworthy?

- Ada Lovelace Institute. (2022). Algorithmic impact assessment: a case study in healthcare. Available at: https://www. adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/algorithmic-impact-assessment-case-study-healthcare

- Ada Lovelace Institute (2020)

- Knowles, B. and Richards, J. (2021) The sanction of authority: promoting public trust in AI. arXiv [online] Available at: https://arxiv.org/abs/2102.04221

- Raji, D., Smart, A. et al. (2020). Closing the AI accountability gap: defining an end-to-end framework for internal algorithmic auditing. Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, p.33–44. [online] Barcelona: ACM. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1145/3351095.3372873

- Leslie, D. (2019). Understanding artificial intelligence ethics and safety: A guide for the responsible design and implementation of AI systems in the public sector. The Alan Turing Institute. Available at: https://www.turing.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2019-06/ understanding_artificial_intelligence_ethics_and_safety.pdf

- METADAC. (2017) Plain language summaries: guidance for METADAC applications. [online]. Available at: https://cpb-eu-w2.wpmucdn.com/blogs.bristol.ac.uk/dist/7/314/files/2017/06/v1.0-Plain-language-guidance-for-METADAC-applications.pdf

- Ada Lovelace Institute. (2022). Algorithmic impact assessment: a case study in healthcare. Available at: https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/algorithmic-impact-assessment-case-study-healthcare

- Ada Lovelace Institute. (2022). NMIP algorithmic impact assessment (AIA) template, Available at: https://www.adalovelaceinstitute. org/resource/aia-template/

- Raji, I.D. and Yang, J. (2019) ABOUT ML: Annotation and Benchmarking on Understanding and Transparency of Machine Learning. In: Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2019). [online] https://arxiv.org/abs/1912.06166

- REFORM (n.d) Data-driven healthcare: regulation & regulators. [online]. Available at: https://reform.uk/research/data-drivenhealthcare-regulation-regulators

- For more details on how the AIA builds on and complements existing AI governance processes in health and other algorithm accountability mechanisms, see Ada Lovelace Institute. (2022). Algorithmic impact assessment: a case study in healthcare. Available at: https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/algorithmic-impact-assessment-case-study-healthcare

- Ada Lovelace Institute. (2022). Algorithmic impact assessment: a case study in healthcare. Available at: https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/algorithmic-impact-assessment-case-study-healthcare

- Ada Lovelace Institute. (2022). NMIP algorithmic impact assessment (AIA) template. Available at: https://www.adalovelaceinstitute. org/resource/aia-template/

- Ada Lovelace Institute. (2022). NMIP algorithmic impact assessment (AIA) template, at: https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/ resource/aia-template/

- D. Leslie (2019)

- Raji, D., Smart, A. et al. (2020). ‘Closing the AI Accountability Gap: Defining an End-to-End Framework for Internal Algorithmic Auditing’ https://arxiv.org/abs/2001.00973

- Ada Lovelace (2020)

- Raji et al (2020)

- Raji, I.D, Mitchell, M. et al (2018) Model cards for model reporting. In: Proceedings of the Conference on Fairness, Accountability and Transparency, p.220-229. [online]. Available at: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3287560.3287596

- European Commission. (2020). White paper on artificial intelligence: a European approach to excellence and trust. Ec.europa. eu.Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications/white-paper-artificial-intelligence-european-approach-excellenceand- trust_en

- Ada Lovelace Institute. (2020). Examining the black box: tools for assessing algorithmic systems. Available at: https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/examining-the-black-box-tools-for-assessing-algorithmic-systems/

- Friedman, B. and Nissenbaum, H. (1996) Bias in computer systems. In: ACM Transactions on Information Systems, 14, p.330-347. [online]. Available at: https://nissenbaum.tech.cornell.edu/papers/Bias%20in%20Computer%20Systems.pdf

- Machines Gone Wrong (n.d) Understanding bias part I. Available at: https://machinesgonewrong.com/bias_i/

- Data Smart Schools (2021) Deb Raji on what ‘algorithmic bias‘ is (…and what it is not . Available at: https://data-smart-schools. net/2021/04/02/deb-raji-on-what-algorithmic-bias-is-and-what-it-is-not/

- Metcalf, J., Elish, M.C., Singh, R., Watkins, E.A. and Moss. E. (2021)

- Ada Lovelace Institute. (2022). Algorithmic impact assessment: a case study in healthcare. Available at: https://www. adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/algorithmic-impact-assessment-case-study-healthcare

- Government of Canada. (2019). Directive on automated decision-making. Gc.ca. Available at: https://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/pol/doc-eng. aspx?id=32592

- BSR. (2019). Google celebrity recognition API human rights assessment. Available at: https://www.bsr.org/reports/BSR-Google- CRAPI-HRIA-Executive-Summary.pdf

Related content

Algorithmic impact assessment: a case study in healthcare

This report sets out the first-known detailed proposal for the use of an algorithmic impact assessment for data access in a healthcare context

Algorithmic impact assessment: AIA template

This template is part of our wider work exploring algorithmic impact assessments (AIAs) in healthcare