Exploring legal mechanisms for data stewardship

A joint publication with the AI Council, which explores three legal mechanisms that could help facilitate responsible data stewardship

4 March 2021

Reading time: 161 minutes

The three legal mechanisms discussed in the report are data trusts, data cooperatives and corporate and contractual models, which can all be powerful mechanisms in the data-governance toolbox.

The report is a joint publication with the AI Council and endorsed by the ODI, the City of London Law Society and the Data Trusts Initiative.

Executive summary

Organisations, governments and citizen-driven initiatives around the world aspire to use data to tackle major societal and economic problems, such as combating the

COVID-19 pandemic. Realising the potential of data for social good is not an easy task, and from the outset efforts must be made to develop methods for the responsible

management of data on behalf of individuals and groups.

Widespread misuse of personal data, exemplified by repeated high-profile data breaches and sharing scandals, has resulted in ‘tenuous’ public trust1 in public and private-sector data sharing. Concentration of power and market dominance, based on extractive data practices from a few technological players, both entrench public concern about data use and impede data sharing and access in the public interest. The lack of transparency and scrutiny around public-private partnerships add additional layers of concerns when it comes to how data is used.2 Part of these concerns comes from the fact that what individuals might consider to be ‘good’ is different to how those who process data may define it, especially if individuals have no say in that definition.

The challenges of the twenty-first century demand new data governance models for collectives, governments and organisations that allow data to be shared for individual and public benefit in a responsible way, while managing the harms that may emerge.

This work explores the legal mechanisms that could help to facilitate responsible data stewardship. It offers opportunities for shifting power imbalances through breaking data silos and allowing different levels of participatory data governance,3 and for enabling the responsible management of data in data-sharing initiatives by individuals, organisations and governments wanting to achieve societal, economic and environmental goals.

This report focuses on personal data management, as the most common type of data stewarded today in alternative data governance models.4 It points out where mechanisms are suited for non-personal data management and sees this area as requiring future exploration. The jurisdictional focus is mainly on UK law, however this report also introduces a section on EU legislative developments on data sharing and, where appropriate, indicates similarities with civil law systems (for example, fiduciary obligations resembling trust law mechanisms).

Produced by a working group of legal, technical and policy experts, this report describes three legal mechanisms which could help collectives, organisations and governments create flexible governance responses to different elements of today’s data governance challenges.

These may, for example, empower data subjects to more easily control decisions made about their data by setting clear boundaries on data use, assist in promoting desirable uses, increase confidence among organisations to share data or inject a new democratic element into data policy.

Data trusts,5 data cooperatives and corporate and contractual mechanisms can all be powerful mechanisms in the data-governance toolbox. There’s no one-size-fits-all

solution and choosing the type of governance mechanism will depend on a number of factors.

Some of the most important factors are purpose and benefits. Coming together around an agreed purpose is the critical starting point, and one which will subsequently determine the benefits and drive the nature of the relationship between the actors involved in a data-sharing initiative. These actors may include individuals, organisations and governments although

data-sharing structures do not necessarily need to include all actors mentioned.

The legal mechanisms presented in this report aim to facilitate this relationship, however the broader range of collective action and coordination mechanisms to address data challenges also need to be assessed on a case-by-case basis. The three mechanisms described here are meant to provide an indication as to the types of approaches, conditions and legal tools that can be employed to solve questions around responsible data sharing and governance.

To demonstrate briefly how purpose can be linked to the choice of legal tools:

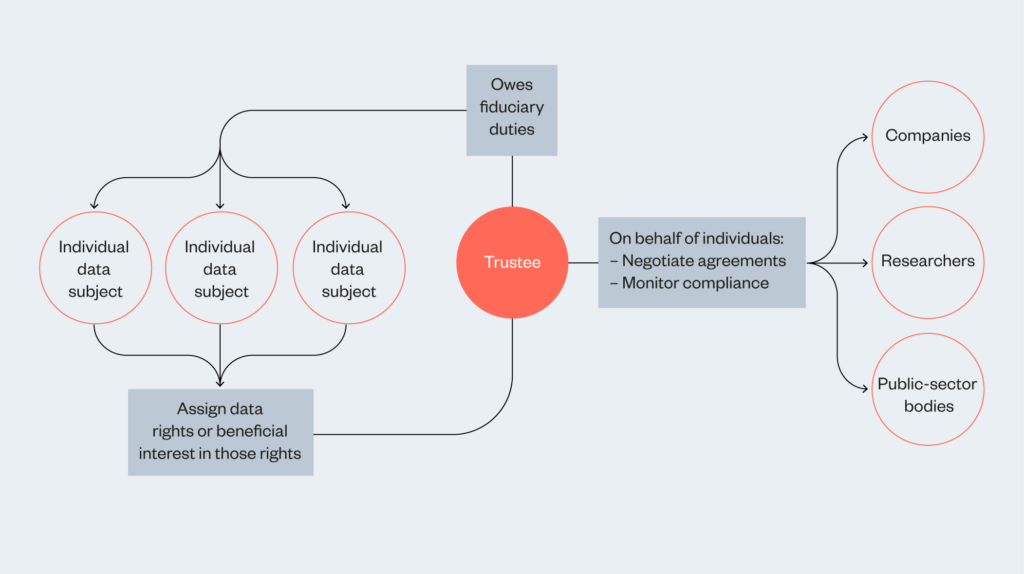

Data trusts create a vehicle for individuals to state their aspirations for data use and mandate a trustee to pursue these aspirations.6 Data trusts can be built with a highly participatory structure in mind, requiring systematic input from the individuals that set up the data trust. It’s also possible to build data trusts with the intention to delegate to the data trustee the responsibility to determine what type of data processing is to the beneficiaries’ interest.

The distinctive elements of this model are the role of the trustee, who bears a fiduciary duty in exercising data rights (or the beneficial interest in those rights) on behalf of the beneficiaries, and the role of the overseeing court in providing additional safeguards. Therefore, data trusts might work better in contexts where individuals and groups wish to define the terms of data use by creating a new institution (a trust) to steward data on their behalf, by representing them in negotiations about data use.

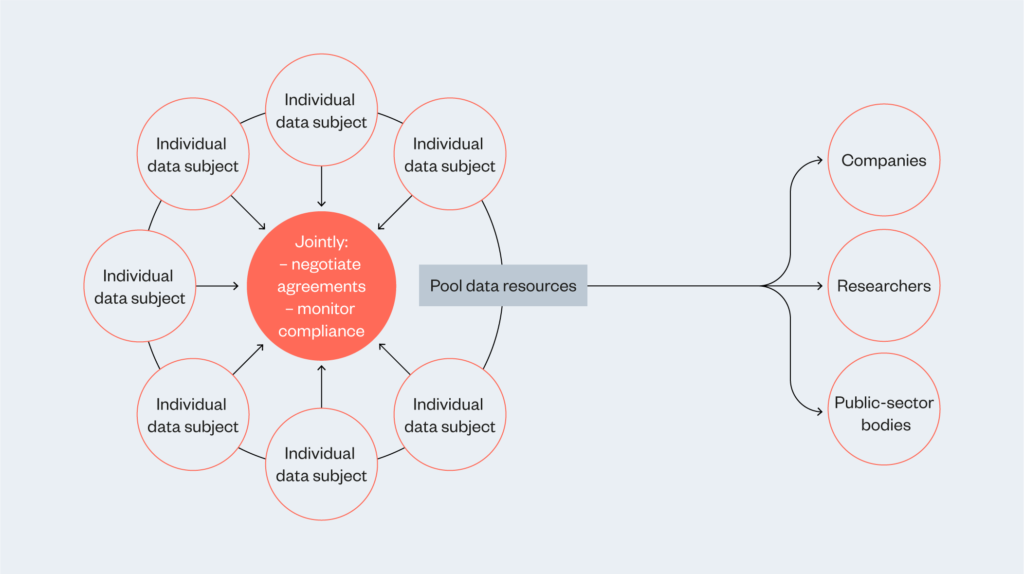

Data cooperatives can be considered when individuals want to voluntarily pool data resources and repurpose the data in the interests of those it represents. Therefore, data cooperatives could be the go-to governance mechanism when relationships are formed between peers or like-minded people who join forces to collectively steward their data and create one voice

in relation to a company or institution.

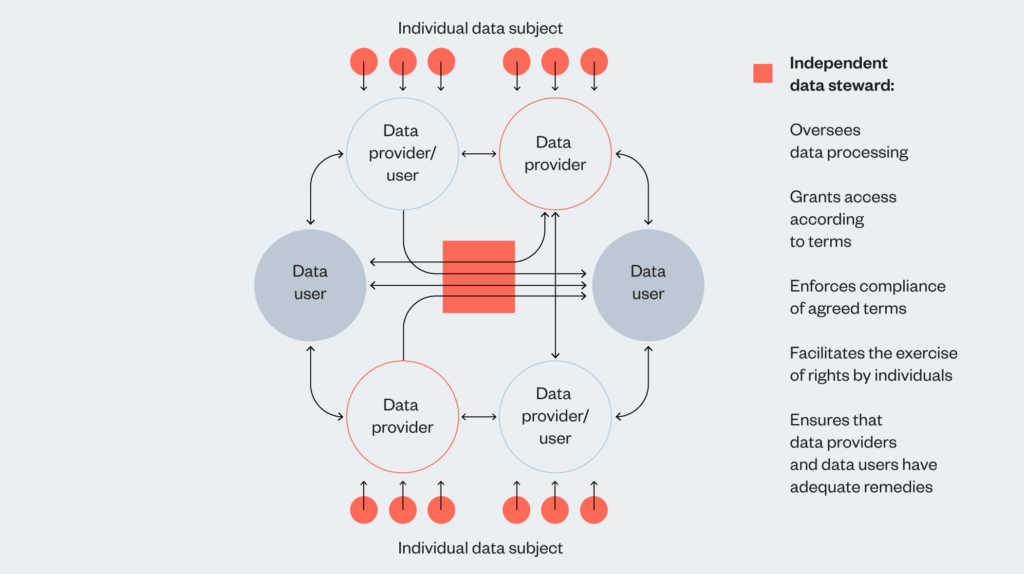

Corporate and contractual mechanisms can be used to design an ecosystem of trust in situations where a group of organisations see benefits in sharing data under mutually agreed terms and in a controlled way. This means these mechanisms might be better suited for creating data-sharing relationships between organisations. The involvement of an independent data steward is envisaged as a means of creating a trusted environment for stakeholders to feel comfortable sharing data with other parties, who they may not know or have had an opportunity to develop a relationship of trust.

This report captures the leading thinking on an emerging and timely issue of research and inquiry: how we can give tangible effect to the ideal of data stewardship: the trustworthy and responsible use and management of data.

Promoting and realising the responsible use of data is the primary objective of the Legal Mechanisms for Data Stewardship working group and the Ada Lovelace Institute, who produced this report, and who view this approach as critical to protecting the data rights of individuals and communities, and unlocking the benefits of data in a way that’s fair, equitable and focused on social benefit.

Chapter 1: Data trusts

Equity as a tool for establishing rights and remedies

Trust law has ancient roots, with the fiduciary responsibilities that sit at its core being traceable to practices established in Roman law. In the UK, the idea of a ‘trust’ as an entity has its origins in medieval England: with many landowners leaving England to fight in the Crusades, systems were needed to manage their estates in their absence.

Arrangements emerged through which Crusaders would transfer ownership of their estate to another individual, who would be responsible for managing their land and fulfilling any feudal responsibilities until their return. However, returning Crusaders often found themselves in disputes with their ‘caretaker’ landowners about land ownership. These disputes were referred to the Courts of Chancery to decide on an appropriate – equitable – remedy. These courts consistently recognised the claims of the returning Crusaders, creating the concepts of a ‘beneficiary’, ‘trustee’ and ‘trust’ to define a relationship in which one party would manage certain assets for the benefit of another – the establishment of a trust.

While the practices associated with trust law have changed over time, their core components have remained consistent: a trust is a legal relationship between at least two parties, in which one party (the trustee) manages the rights associated with an asset for the benefit of another (the beneficiary).7 Almost any right can be held in trust, so long as the trust meets three conditions:

- there is a clear intention to establish a trust

- the subject matter or property of the trust is defined

- the beneficiaries of the trust are specified (including as a conceptual

category rather than nominally).

In the centuries that followed their emergence, the Courts of Chancery have played an important role in settling claims over rights and creating remedies where these rights have been infringed. Core to the operation of these courts is the concept of equity – that disputes should be settled in a way that is fair and just. In centring this concept in their jurisprudence, they have found or clarified new rights or responsibilities that might not be directly codified in Common Law, but which can be adjudicated according to legal principles of fairness. This has enabled the courts to develop flexible and innovative responses in situations where there may be gaps in Common Law, or where the strict definitions of the Common Law are ill-equipped to manage new social practices.

It is this ability to flex and adapt over time that has ensured the longevity of trusts and trust law as a governance tool, and it is these characteristics that have attracted interest in current debates about data governance.

Why data trusts?

Today’s data environment is characterised by structural power imbalances. Those with access to large pools of data – often data about individuals – can leverage the value of aggregated data to create products and services that are foundational to many daily activities.

While offering many benefits, these patterns of data use can create new forms of vulnerability for individuals or groups. Recent years have brought examples of how new uses of data can, for example, create sensitive data about individuals by combining datasets that individually seemed innocuous, or use data to target individuals online in ways that might lead to discrimination or social division.

Today, these rights are typically managed through service agreements or other consent-based models of interaction between individuals and organisations. However, as patterns of data collection and use evolve, the weaknesses associated with these processes are becoming clearer. This has prompted re-examination of consent as a foundation for data exchange and the long-term risks associated with complex patterns of data use.

The limitations of consent as a model for data governance have already been well-characterised. Many terms and conditions are lengthy and difficult to understand, and individuals might not have the ability, knowledge or time to adequately review data access agreements; for many, interest in consent and control is sparked only after they have become aware of data misuse; and the processes for an individual to enact their data rights – or receive redress for data misuse – can be lengthy and inaccessible.8

Moreover, as interactions in the workplace, at home or with public services are increasingly shaped by digital technologies, there is pressure on individuals to ‘opt in’ to data exchanges, if they are to be able to participate in society. This reliance on digital interactions exacerbates power imbalances in the governance system.

Approaches to data governance that concentrate on single instances of data exchange also struggle to account for the pervasiveness of data use, much of this data being created as a result of a digital environment in which individuals ‘leak’ data during their daily activities. In many cases, vulnerabilities arising from data use come not from a single act of data processing, but from an accumulation of data uses that may have been innocuous individually, but that together form systems that shape the choices individuals make in their daily lives – from the news they read to the jobs adverts they see. Even if each single data exchange is underpinned by a consent-based interaction, this cumulative effect – and the long-term risks it can create – is something that existing policy frameworks are not well-placed to manage.9

Nevertheless, it needs to be pointed out that the foundational elements of the GDPR that govern data processing are principles such as data protection by design and by default, and mechanisms such as data protection impact assessments (DPIAs), which are designed to help preempt potential risks as early as possible. These are legal obligations and a prerequisite step before individuals are asked for consent.10 Therefore, it is important to highlight the broader compliance failures as well as the limitations of the consent mechanism which play a significant role in creating imbalances of power and potential harm.

The imbalances of power or ability of individuals and groups to act in ways that define their own future create a data environment that is in some ways akin to the feudal system which fostered the development of trust law. Powerful actors are able to make decisions that affect individuals, and – even if those actors are expected to act with a duty of care for individual rights and interests – individuals have limited ability to challenge these structures.

There are also limited mechanisms allowing individuals who want to share data for public benefit to do so via a structure that warrants trust. In areas where significant public benefit is at stake, individuals and communities may wish to take a view on how data is used, or press for action to use data to tackle major societal challenges. At present, the vehicles for the public to have such a voice are limited.

For the purposes of this report, trust law is explored as a new form of governance that can achieve goals such as:

- increase an individual’s ability to exercise the rights they currently have in law

- redistribute power in the digital environment in ways that support individuals and groups to proactively define terms of data use

- support data use in ways that reflect shifting understandings of social value and changing technological capabilities.

The opportunities for commercial or not-for-profit organisations focused on product or research development, or which are seriously concerned about implementing a high degree of ethical obligations when it comes to data pertaining to their customers (and empower these customers not only to make active choices about data management, but also benefit from insights from this data) are briefly discussed in the section on ‘Opportunities for organisations to engage with data trusts’.

What is a data trust?

A data trust is a proposed mechanism for individuals to take the data rights that are set out in law (or the beneficial interest in those rights) and pool these into an organisation – a trust – in which trustees would exercise the data rights conferred by the law on behalf of the trust’s

beneficiaries.

Public debates about data use often centre around key questions such as who has access to data about us and how is it used. Data trusts would provide a vehicle for individuals and groups to more effectively influence the answers to these questions, by creating a vehicle for individuals to state their aspirations for data use and mandate a trustee to pursue these aspirations. By connecting the aspiration to share data to structures that protect individual rights, data trusts could provide alternative forms of ‘weak’ democracy, or new mechanisms for holding those in power to account.

The purposes for which data should be used, or data rights exercised, would be specified in the trust’s founding documents, and these purposes would be the foundation for any decision about how the trust would manage its assets. Mechanisms for deliberation or consultation with beneficiaries could also be built into a trust’s founding charter, with the form and function of those mechanisms depending on the objectives and intentions of the parties creating the trust.

Trustees and their fiduciary duties

Trustees play a crucial role in the success of such a trust. Data trustees will be tasked with stewarding the assets managed in a trust on behalf of its beneficiaries. In a ‘bottom-up’ data trust,11 the beneficiaries will be the data subjects (whose interests may include research facilitation, etc.). Data trustees will have a fiduciary responsibility to exercise (or leverage the beneficial interest inherent in) their data rights. Data trustees may seek to further the interests of the data subjects by entering into data-sharing agreements on their behalf, monitoring compliance with those agreements or negotiating better terms with service providers.

By leveraging the negotiating power inherent in pooled data rights, the data trustee would become a more powerful voice in contract negotiations, and be better placed to achieve favourable terms of data use than any single individual. In so doing, the role of the data trustee would be to empower the beneficiaries, widening their choices about data use beyond the ‘accept or walk away’ dichotomy presented by current governance structures. This role would require a high level of skill and knowledge, and support for a cohort of data trustees would

be needed to ensure they can fulfil their responsibilities.

Core to the rationale for using trust law as a vehicle for data governance is the fiduciary duty it creates. Trustees are required to act with undivided loyalty and dedication to the interests and aspirations of the beneficiaries.12 The strong safeguards this provides can create a foundation for data governance that gives data subjects confidence that their data rights are being managed with care.

Adding to these fiduciary duties, the law of equity provides a framework for accountability. If not adhering to the constitutional terms of a trust, trustees can be held to account for their actions by the trust’s beneficiaries (or the overseeing Court acting on their behalf) or an

independent regulator. Not only is a Court’s equitable jurisdiction to supervise, and intervene if necessary, not easily replicable within a contractual or corporate framework, the importance of the fact that equity relies on ex-post moral standards and emphasises good faith cannot be overestimated.

The flexibility offered by trusts also offers benefits in creating a governance system that is able to adapt to shifting patterns of data use. A range of subject matters or application areas could form the basis of a trust, allowing trusts to be established according to need: trusts would therefore allow co-evolution of patterns of data use and regulation.

In conditions of change or uncertainty around data use, this flexibility offers the ability to act now to promote some types of data use, while creating space to change practices in the future.

A further advantage of trust law is its ability to enable collective action while providing institutional safeguards that are commensurate to the vulnerabilities at stake. It is possible to imagine situations in which individuals might group together on the basis of shared values or

attitudes to risk, and seek to use this shared understanding to promote data use. In coming together to define the terms of a trust, individuals would be able to express their agency and influence data use by defining their vision. The beneficiaries’ interest can be expressed in more restrictive or prudential terms, or may include a broader purpose such as the furthering of research or influencing patterns of data use. Current legal frameworks offer few opportunities to enable group action in this way.

The relationship between data rights and trusts

Almost any right or asset can be placed in trust. Trusts have already been established for rights relating to intellectual property and contracts, alongside a range of different types of property, including digital assets, and have proven themselves to be flexible in adapting to different types of asset across the centuries.13

Understanding what data rights can be placed in trust, when those rights arise and how a trust can manage those rights will be crucial in creating a data trust. Further work will be required to analyse the sorts of powers that a trustee tasked with stewarding those rights might be able to wield, and the advantages that might accrue to the trust’s beneficiaries as a result.

In the case of data about individuals, the GDPR confers individual rights in respect of data use, which could in principle be held in trust. These include ‘positive’ rights such as portability, access and erasure that would appear to be well-suited to being managed via a trust.

The development of data trusts will require further clarity on how these rights can be exercised. There is already active work on the extent to which (and conditions according to which) those positive rights may be mandatable to another party to act on behalf of an individual, such as a trustee. Opinions on the issue differ among GDPR experts and publication of the European Commission’s draft Data Governance Act raises new questions about how and whether data rights might be delegated to a trust. The feasibility of data trusts however does not hinge on a positive answer to this delegability question, since trust law offers a potential workaround that does not require any right transfer.14

As trusts develop, they will also encounter new questions about the limitations of existing rights and what happens when different rights interact.15 For example, organisations can analyse aggregated datasets and create profiles of individuals, generating inferences about their likely preferences or behaviours. These profiles – created as a result of data analysis and modelling – would typically be considered the intellectual property of the entity that conducted the analysis or modelling. While input data might relate to individuals, once aggregated and anonymised to a certain extent, it would no longer be considered as personal data under the GDPR. However, if inferences are classified as personal data within the scope of the GDPR, individual data-protection rights should apply. Nevertheless, as some authors have explained, exercising data rights on inferences classified as personal data remains limited, and particularly in the case of data portability could give rise to different tensions with trade secrets and intellectual property.16

An example helps illustrate the challenges at stake: in the context of education technologies, data provided by a student – from homework to online test responses – would be portable under the rights set out in the GDPR, but model-generated inferences about what learning methods would be most effective for that student could be considered as the intellectual property of the training provider. The establishment of a trust to govern the use of pupil data (just like any other ‘bottom-up’ data trust) could help shed light on those necessarily contested borders between intellectual property (IP) rights – that arise from creative input in developing the models that produce individual profiles – and personal data rights.

There will never be a one-size-fits-all answer on where to draw these boundaries between IP and personal data.17 Instead, what is needed is a mechanism for negotiating these borders between parties involved in data use. In such cases, data trustees could have a crucial public advocacy function in negotiations about the extent to which such inferences fall within the scope of portability provisions.

Examining the data rights that might be placed in trust points to important differences between the use of trusts as a data governance tool and their traditional application.

Typically, assets placed in trust have value at the time the trust is created. In contrast, modern data practices mean that data acquires value in aggregate – it is the bringing together of data rights in a trust that gives trustees power to influence negotiations about data use that would elude any individual. Whereas property is typically placed in trust to manage its value, data (or data rights) would be placed in trust in part to create value.

Another difference can be found in the ease with which assets can typically be removed from a trust. Central to the trusts proposition is that individuals would be able to move their data rights between trusts, within an ecosystem of trust entities that provide a choice in different types of data use.

The ecosystem of data trusts that would enable individuals to make choices between different approaches to data use and management presupposes the ability to switch from one trust to another relatively easily, probably more easily than in traditional trusts.

These differences need not present a barrier to the development of data trusts. The history of trusts demonstrates the flexibility of this branch of law, and trusts can have a range of properties or ways of working that are designed to match the intent of their creators.

Alternatives to trust law

The fiduciary duties owed by trustees to beneficiaries can be achieved by other legal models. For example, contractual frameworks or principal-agent relationships, can create duties between parties, with strong consequences if those duties are not fulfilled. Regulators can also perform a function similar to fiduciary responsibilities, for example in cases where imbalances of market power might have detrimental impacts on consumers. However, each has its limitations. For example:

- Contracts allow use of data for a purpose. Coupled with an audit function, these can ensure that data is used in line with individual wishes, and – at least for simple data transactions – contracts would require less energy to establish than a trust. However, effective auditing relies on the ability to draw a line from the intention of those entering a contract to the wording of the contract then to its implementation. Given the complexity of patterns of data use – and the fact that many instances of undesirable data use arise from multiple inconsequential transactions – this function may be difficult to achieve. Due to their obligation of undivided loyalty, a trustee may be better placed and motivated to map intent to use and understand potential pitfalls arising

from the interactions between data transactions. - Agents can be tasked with acting on behalf of an individual, taking a fiduciary responsibility in doing so. However, the interaction between an individual and their agent does not accommodate as easily the collective dimension enabled by the establishment of a trust, and it is in this collective dimension that the ability to disrupt digital power relationships lies. Another issue associated with the use of agents is accountability. Structures would be needed to ensure that agents could be held accountable by individuals, if they failed in their responsibilities. In comparison, under trust law, the Courts of Chancery (and the associated institutional safeguards) present a much stronger accountability regime.

Many jurisdictions do not have an equivalent to trust law. However, they may have mechanisms that could fulfil similar functions. For example, while Germany does not operate a trust law framework, some institutions have fiduciary responsibilities built into their very structure, with institutions such as Sparkassen, banks that operate on a cooperative and not-for-profit basis, taking on a fiduciary responsibility for their customers. Studying such mechanisms might uncover ways of delivering the key functions of trust law – stewarding the rights associated with data and delivering benefits for individuals, communities and society with strong safeguards against abuse.

Developing data trusts

Recent decades have brought radical changes in patterns of data collection and use, and the coming years will likely see further changes, many of which would be difficult to predict today. In this context, society will need a range of governance tools to anticipate and respond to emerging digital opportunities and challenges. In conditions of uncertainty, trusts offer a way of responding to emerging governance challenges, without requiring legislative intervention that can take time to produce (and is more difficult to adapt once in place).

Trusts occupy a special place in the UK’s legal system, and the skills and experience of the UK’s legal community in their development and use means it is well-placed to lead the development of data trusts. The next wave in the development of these governance mechanisms will require further efforts to analyse the assets that will be held by a data trust, investigate the powers that trustees may hold as a result, and consider the different forms of benefit that may arise as a result. Those seeking to capture this opportunity will need to:

- clarify the limits of existing data rights

- identify lessons from other jurisdictions in the use of fiduciary responsibilities to underpin data governance

- support pilot projects that assess the feasibility of creating data trusts as a framework for data governance in areas of real-world need.

Problems and opportunities addressed by data trusts

Data trusts have the potential to address some of the digital challenges we face and could help individuals better position themselves in relationship to different organisations, offering new mechanisms for chanelling choices related to how their data is being used.

While organisations could also form data trusts, this section will deal only with data trusts where the beneficiaries are individuals (data subjects). Also, while trusts could manage rights over non-personal data, this section takes as starting point the opportunities coming from individuals delegating their rights (or beneficial interest therein) over personal data. In contexts where non-personal data is managed, the practical challenges in distinguishing personal and non-personal data need to be acknowledged, and it needs to be seen how managing mixed data sets influence the structure and running of a data trust.

There are a number of issues that might arise from setting up a data trust, which aims to balance the asymmetries between those who have less power and are more vulnerable (individuals or data subjects) and those who are in a more favoured position (organisations or data controllers). This section aims at briefly presenting a number of caveats in relation to data trusts and the ecosystem they create, however it should be noted that information asymmetries could also exist between individuals and trusts, not only between individuals and organisations.18

1. Purpose of the trust and consent

Trusts are usually established for defined purposes set out in a constitutional document. The data subjects will either come together to define their vision about the purposes of data use or will need to adhere to an established data trust and be well-informed about the purposes of the trust and how data or data rights are handled. In either case, it is of the utmost importance that those joining a data trust can do so in full awareness of the trust’s terms and aims.

This raises important ‘enhanced consent’ questions: what mechanisms, if any, are available to data trustees to ensure informed and meaningful consent is achieved? Will the lack of mechanisms for deliberation or consultation with beneficiaries involve liability for the trustees? What would the trustee role be in a participatory structure (active or purely managerial)? Might data trustees for instance draw upon the significant body of work in medical ethics to delineate best practice in this respect?

This set of questions is related to the issues raised in the next section, regarding the status, oversight and required qualifications of data trustees. Important questions arise around how expertise is attracted to this position when, as we will see below, the challenges for remunerating this role and the responsibilities and liabilities of trustees are significant.

2. The role of the trustee

The trustee will be in charge of managing the relationship between the trust’s beneficiaries and the organisations the trust interacts with. Trustees will have a duty of undivided loyalty to the beneficiaries (understood here as the data subjects whose data rights they manage) and they would be responsible for skilfully negotiating the terms of use or access to the beneficiaries’ data. They could also be held responsible if terms are less than satisfactory or if beneficiaries find fault with their actions (in which case the burden of proof is reversed, and it is for the data trustee to demonstrate that they have acted with undivided loyalty).

There are open questions as to if and how beneficiaries will be able to monitor the trustees’ judgement and behaviour and how beneficiaries will be able to identify fault when complex data transactions are involved. More complexity is added also if an ecosystem of data trusts is developed, where one person’s data is spread across several trusts.

At the same time, in the context of increased concerns coming from combining different datasets, in a scenario where one data trust manages a particular dataset about its beneficiaries and another trust manages a different dataset, where the combination of these two datasets could result in harm, should there be mechanisms for trusts to cooperate in preventing such harms? Or would trustees just inform beneficiaries of potential dangers and ask them to sign a liability waiver?

If and when a data trust relies on a centralised model (rather than a decentralised one, whereby the data remains wherever it is, and the data trustee merely leverages the data rights to negotiate access, etc.), one of the central attributions of the trustees will be to ensure the privacy and security of the beneficiaries’ data. Such a task would involve a high degree of risk and complexity (hence the likely preference for decentralised models).

It is unclear what type of technical tools or interfaces will be needed in order for trustees to access credentials in a secure way, for example, and who will make these significant investments in the technical layer. Potential inspiration could come from the new Open Banking ecosystem, where data sharing is enabled by secure Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) which rely on the banks’ authentication methodologies, so that third-party providers do not have to access users’ credentials.

Managing such demanding attributions raises questions related to what will be the triggers, incentives and training required for trustees to take up such a complex role. Should there be formal training and entry requirements? Could data trustees eventually constitute a new type of profession, which could give rise to a ‘local’ and potentially more nimble layer of professional regulation (on top of court oversight and potential legislative interventions), not unlike the multilayered regulatory structure that governs medical practice today?

3. Incentives and sustainability of data trusts

The data trust ecosystem model suggests the importance of competition between trusts for members, yet at this stage it is not clear how enough competition between trusts will emerge. At the same time, it is presumed that a data trust would work best when it operates on behalf of a large number of people. This gives the data trust a bargaining power position in relation to different organisations such as companies and public institutions. Will this create a dependence on network effects, and how can the negative implications be addressed?

Moreover, there are questions related to the funding model and incentives structure underlying the sustainability of data trusts. What will attract individuals to a data trust? For example, if the concern of the beneficiaries is to restrict and to protect data, will the trust be able to generate an income stream or will the trust rely on funding from other sources (e.g. from beneficiaries, philanthropists, etc.)? At the same time, if potential income streams are maximised depending on the use of the data, what are the implications for privacy and data protection?

In addition, what happens when individuals are simply unaware or uninterested in joining a data trust? Might they be allocated to a publicly funded data trust, on the basis of arguments similar to those that were relied on when making pension contributions compulsory? If so, what would constitute adequate oversight mechanisms?

When individuals are interested in joining a data trust, will they be lured by the promise of streamlining their daily interaction with data-reliant service providers, effectively relying on data trusts as a lifestyle, paid-for intermediary service providing peace of mind when it comes to safeguarding personal data? Will individuals be motivated to join a data trust in order to contribute to the common good in a way that does not entail long-term data risks? Will there be monetary incentives for people joining a data trust (whereby individuals would obtain monetary compensation in exchange for providing data)? Should some incentives structures – such as monetary rewards – be controlled and regulated, or in some cases altogether banned?

There are a number of possible funding models for data trusts:

- privately funded

- publicly funded

- charging a fee or subscription from data trust beneficiaries (the individuals or data subjects) in return for streamlining and/or safeguarding their data interactions

- charging a fee or subscription from those who use the data (organisations)

- charging individuals for related services

- a combination of the above.

The different funding options will have both sustainability, and larger data ecosystem implications. If the trust needs to generate revenue by charging for access to the data it stewards or for related services, the focus might start to levitate towards the viability and performance of the trust. The trusts’ performance will correlate with the demand side (organisations using the trust’s beneficiaries’ data), how many people join a data trust (potentially reinforcing network effects) and which data trust can compete better. Will these interdependencies diminish the data trusts’ role as a rebalancing tool for adjusting asymmetries of power and consolidating the position of the disadvantaged?

At the same time, if the data trust operates on a model where the beneficiaries are charged for the service, much depends on how that service is understood. If the focus is on monetary rewards, and the latter are not regulated, the expectations of return from the data trust will increase, hence affecting the dynamics of the relationships. For example, if the data trusts’ funding model implies companies pay back profit on the data used, they will have to make a number of decisions regarding their profitability and viability on the market. Will this reinforce some of the business models that are considerably criticised today, such as the dominant advertising based model?

In the case of publicly funded data trusts, public oversight mechanisms and institutions will need to be developed. At the moment, it is unclear who will be responsible for ensuring funds are transparently allocated based on input from individuals, communities and data-sharing needs. The currently low levels of data awareness also raise concerns about ways of building genuine and adequate engagement mechanisms. Further, the impact, benefit, results or added value created by the data trust will need to be demonstrated. This calls for building transparency and accountability means that are specific to publicly funded data trusts, grafting themselves on top of existing fiduciary duties (and Court oversight mechanisms).

4. Opportunities for organisations to engage with data trusts

Data trusts could offer opportunities for commercial or not-for-profit organisations in a variety of ways. Some of the benefits have been briefly mentioned in the introductory section, pointing to reputational benefits, legal compliance and future-proofing data governance practices. In this respect, one may imagine a scenario whereby large corporate entities (such as banks for instance) are keen to go beyond mere regulatory compliance by sponsoring a data trust in a bid to show how seriously they take their ethical responsibilities when it comes to personal data.

Such a ‘sponsored data trust’ would be strictly separate from the bank itself (absence of conflict of interest would have to be very clear). It could be flagged as enabling the bank’s clients to ‘take the reins’ of their data and benefit from insights derived from this data. All the data that would normally be collected directly by the bank would only be so collected on the basis of terms and conditions negotiated by the data trustee on behalf of the trust’s beneficiaries. The trustee could also negotiate similar terms (or negotiate to revise terms of existing individual agreements) with other corporate entities (supermarkets for instance).

Other potential benefits for corporate and research bodies are around the trusts’ ability to enable access to potentially better quality data that fits organisations’ needs and enables a more agile use of data. This reduces overhead and provides more ease of mind, based on the trustees’ fiduciary responsibility to the data subjects. A trustee would be able to spot and prevent potential harms, therefore reducing liability issues for organisations that could have otherwise arisen from engaging with individual data subjects directly. At the same time, trusts offer a way of responding to emerging governance challenges, without requiring legislative intervention that can take time to produce (and is more difficult to adapt once in place). A broader discussion about opportunities for commercial or not-for-profit organisations could be

considered for a future report.

Mock case study: Greenfields High School

Greenfields High School is using an educational platform to deliver teaching materials, with homework being assigned by online tools that track student learning progress, for example recording test scores. The data collected is used to tailor learning plans, with the aim of improving student performance.

Students, parents, teachers and school leadership have a range of interests

and concerns when it comes to these tools:

- Students wish to understand what data is collected about them, how it is used and for how long it is kept. Parents want assurances about how their children’s data is used, stored, and processed.

- Parents, teachers, and school leadership wish to compare their performance against that of other schools, by sharing some types of data.

- The school wants to keep records of educational data for all pupils for a number of years to track progress. It also wants to be able to compare the effectiveness of different learning platforms.

- The company providing the learning platform requires access to the data to improve its products and services.

How would a data trust work?

A data trust is set up, pulling together the rights pupils and parents have over the personal data they share with the education platform provider. It tasks a data trustee with the exercise of those rights with the aim of negotiating the terms of service to the benefit and limits established by the school, parents and pupils. It also aims at maximising the school’s ability to evaluate different types of tools (and possibly pool this data with other schools), within an agreed scope of data use that maintains the pupils’ and parents’ confidence that they are minimising the risks associated with data sharing.

The trust will be able to leverage its members’ rights to data portability and/or access (under the GDPR) when the school discusses onwards terms of data usewith the educational platform service provider.

The data trust includes several schools who have joined a group of common interest in a certain educational approach. This group is overseen by a board. One of the persons sitting on that board is appointed as data trustee.

Chapter 2: Data cooperatives

Why data cooperatives?

The cooperative approach is attractive in situations where there is a desire to give members an equal stake in the organisation they establish and an equal say in its management, as for example with traditional mutuals – businesses owned by and run for the benefits of their members – which are common in financial services, such as building societies. As the business is owned and run by its members, the cooperative approach can be seen as a solution to a growing sense of powerlessness people feel over businesses and the economy.19

The cooperative approach in the context of data stewardship can be explored in examples where groups have voluntarily pooled data resources in a commonly owned enterprise, and where the stewardship of that data is a joint responsibility of the common owners. The aim of such enterprises is often to give members of the cooperative more control over their data and repurpose the data in the interests of those represented in it, as opposed to the erection of defensive restrictions around the use of data to prevent activities that conflict with the interests of data subjects (especially but not exclusively with respect to activities that threaten to breach their privacy). In other words, cooperatives tend to have a positive rather than a negative agenda, to achieve some goal held commonly by members, rather than to avoid some outcome resisted by them.

This chapter looks at some examples of data cooperatives, the problems and opportunities they address and patterns of data stewardship. It explores the structure and characteristics of cooperatives and provides a summary of the challenges presented by the cooperative model, together with descriptions of alternative approaches.

What is a cooperative?

A cooperative typically forms around a group that perceives itself as having collective interests, which it would be better to pursue jointly than individually. This may be because they have more bargaining power as a collective, because some kind of network effect means the value for all increases if resources are pooled, or simply because the members of the cooperative do not want to cede control of the assets to those outside the group. Cooperatives are typically formed to create benefits for members or to supply a need that was not being catered for by the market.

The International Cooperative Alliance or ICA20 is the global steward of the Statement on the Cooperative Identity, which defines a cooperative as an ‘autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social, and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly-owned and democratically controlled enterprise.’

According to the ICA there are an estimated three million cooperatives operating around the world,21 established to realise a vast array of economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations. Examples include:

- Consumer cooperatives, which provide goods and services to their members/owners, and so serve the community of users. They value service and low price above profit, as well as being close to their customers. They might produce goods such as utilities, insurance or food, or services such as childcare.22 They might be ‘buyers’ clubs’, intended to enable the amalgamation of buyers’ power in order to reduce prices. Credit unions are also examples of consumer cooperatives, which mutualise loans based on social knowledge of local conditions and members’ needs, and are owned by the members and therefore able to devote more capital to members’ services rather than profits for external owners.23

- Housing cooperatives take on a range of forms, from shared ownership of the entire asset to management of the leasehold or managing tenants’ participation in decision-making.

- Worker cooperatives, where the entity is owned and controlled by employees.

- Agricultural cooperatives, which might be concerned with marketing, supply of goods or sharing of machinery on behalf of members. Many agricultural cooperatives in the US are of significant size: the largest, for example, had revenues of $32 billion in 2019.24 These cooperatives are formed to address a market power imbalance created by small producers and large distributors or buyers – power asymmetries that are also experienced by individuals in the data ecosystem.

The estimated three million cooperatives subscribe to a series of cooperative values and principles.25 Values typically include self-help,self-responsibility, democracy, equality, equity, solidarity, honesty and transparency, social responsibility and an ethics of care.26 Fundamental cooperative characteristics include: voluntary and open membership, democratic member control (one member, one vote), member benefit and economic participation (with surpluses shared on an equitable basis), and autonomy and independence.27

Cooperatives in the UK: characteristics and legal structures

According to Co-operatives UK28 there are more than 7,000 independent cooperatives in the UK, operating in all parts of the economy and collectively contributing £38.2 billion to the British economy.29

UK law does not provide a precise definition of a cooperative, nor is there a prescribed legal form that a cooperative must take. According to Co-operatives UK, a cooperative in the UK can generally be taken to be any organisation that meets the ICA’s definition of a cooperative and espouses the cooperative values and principles set out in the Statement on the Cooperative Identity.30 This status can be implemented via many different unincorporated and incorporated legal forms. Deciding which one is best will depend on a number of case-specific factors, including the level of liability members are willing to expose themselves to, and the way members want the cooperative to be governed.

A possible, and seemingly obvious, choice of legal form is registering as a cooperative society under the Co-operative and Community Benefit Societies Act 2014.31 This Act consolidated a range of prior legislation and helped to clarify the legal form for cooperative societies in the UK (different rules apply for registration of a credit union under the Credit Unions Act 1979). Subsequent guidance from the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) on registration, and the Charity Commission on share capital withdrawal allowances, have further clarified and codified the regulatory regime for cooperative societies. In particular, to register as a cooperative society under the Act, it must be a ‘bona fide co-operative society’. The Act however does not precisely define what is included as a bona fide co-operative society. In its guidance, the FCA adopted the definition in the ICA’s Statement on the Cooperative Identity and says it considers it an indicator that the condition for registration is met where the society puts the values from the ICA’s Statement into practice through the principles set out in the Statement.32

The cooperative society form is widely used by all types of cooperatives. Registration under the 2014 Act imposes a level of governance through a society’s rules and a level of transparency through certain reporting requirements that has some common ground with Companies Acts requirements for other types of organisations.

However, as noted above, this is not the only legal form available for a cooperative, and alternative legal forms that can be used include a private company limited by shares and a private company limited by guarantee. For a more detailed exploration of the options Co-operatives UK has published guidance,30 and has a ‘Select-a-Structure’ tool on its website.34

Cooperatives and data stewardship

For the purposes of this report we see data cooperatives as cooperative organisations (whatever their legal form) that have as their main purpose the stewardship of data for the benefit of their members, who are seen as individuals (or data subjects).35 This is in contrast to stewardship of data primarily or exclusively for the benefit of the community at large.

Under the Co-operative and Community Benefit Societies Act 2014,if the emphasis is to benefit a wider community then the appropriate legal form would be a community benefit society.

As for cooperative societies, other legal forms could also be used to achieve the same aims and deciding which is best will depend on a number of case-specific factors. However, that is not to say that a cooperative whose aim is to benefit its members might not also benefit wider society – we will see examples later (e.g. Salus Coop) where members’ benefits are also intended to benefit wider society. Indeed, where members see the wider benefits as their own priorities (as with philanthropic giving), the distinction between members’ benefits and social benefits may be hard to discern.

In a data cooperative, those responsible for stewarding the data act in the context of the collective interests of the members and – depending on how the cooperative is governed – may have to advance the interests of all members at once, and/or achieve consensus over whether an action is allowed.

The stewardship of data may be (and with increasing tech adoption is increasingly likely to be) a secondary function to the main purpose of a cooperative. For example, if the cooperative is enabled by technology, such as through the use of a social media platform, then it will routinely produce data that it may be able to capture. If so, this data might be of use to the cooperative’s own operations in future. Some of these groups have been described as social machines.36

Examples of areas where valuable data may be produced are medical applications, interest groups, such as religious or political groups, fitness, wellbeing and self-help groups, particularly including the quantified self movement, and gaming groups. While questions around the management and use of data produced by cooperatives through their ordinary business will become increasingly important (as with other types of organisations that produce data as part of their business) this is not our focus here.

Data cooperatives versus data commons

In their collaborative, consensual form, data cooperatives are similar to data commons. A commons is a collective set of resources that may be: owned by no one; jointly owned but indivisible; or owned by an individual with others nevertheless having rights to usage (as with some types of common land). Management of a commons is typically informal, via agreed institutions and social norms.37

The distinction between commons and cooperatives is blurred; one possible marker is that a commons is an arrangement where the common resource is undivided, and the stakeholders all have equal rights, whereas in a cooperative, the resources may have been owned by the members and brought into the cooperative. The cooperative therefore grows or shrinks as resources are brought in or out as members join or leave, whereas the commons changes organically, and its stakeholders use but do not contribute directly to the resources.

In the case of data, the cooperative model would imply that data was brought to and withdrawn from the cooperative as members joined and left. A data commons implies a body of data whose growth or decline would be independent of the identity and number of stakeholders.

The governance of commons can provide sustainable support for public goods,38 and data commons are often written and theorised about.39 However, as this report is focused on existing examples of practice, in this respect it is difficult to identify actual paradigms of data commons (either intended as such, or merely as institutions whose governance happens to meet Ostrom’s principles).40 Hence, while data commons may possibly be an exciting way forward, and while there are indeed some domains where a commons approach might be appropriate (such as OpenStreetMap and Wikidata), the prospects of their emergence from the complex legal position surrounding data at the time of writing are not strong, so will not be discussed further in this report.

Examples of cooperatives as stewards of data

For the purpose of this report, data cooperatives are seen as cooperative organisations (irrespective of their legal form) that have as their main purpose the stewardship of data for the benefit of its members. This section focuses on examples from the data cooperative space, sharing remarks on governance, approach to data rights and sustainability. Although they take different legal forms (particularly as they are not all UK-based projects) all are working along broadly cooperative principles.

1. Salus Coop

Salus Coop is a non-profit data cooperative for health research (referring not only to health data, but also lifestyle-related data more broadly, such as data that captures the number of steps a person takes in a day), founded in Barcelona by members of the public in September 2017. It set out to create a citizen-driven model of collaborative governance and management of health data ‘to legitimize citizens’ rights to control their own health records while facilitating data sharing to accelerate research innovation in healthcare’.41

Governance: Salus have developed a ‘common good data license for health research’ together with citizens through a crowd-design mechanism,42 which it describes as the first health data-sharing license. The Salus CG license applies to data that members donate and specifies the conditions that any research projects seeking to use the member data must adhere to.43 The conditions are:

- health only: the data will only be used for biomedical research activities and health and/or social studies

- non-commercial: research projects will be promoted by entities of general interest, such as public institutions, universities and foundations

- shared results: all research results will be accessible at no cost maximum privacy: all data will be anonymised and unidentified before any use

- total control: members can cancel or change the conditions of access to their data at any time.

Data rights: Individual members will have access to the data they’ve donated, but Salus will only permit third-party access to anonymised data. Salus describes itself as committed to ensuring, and requires researchers interacting with the data to ensure, that: individuals have the right to know under what conditions the data they’ve contributed will be used, for what uses, by which institutions, for how long and with what levels of anonymisation; individuals have the right to obtain the results of studies carried out with the use of data they’ve contributed openly and at no cost; and any technological architecture used allows individuals to know about and manage any data they contribute.

Note therefore that Salus meets the definition of a data cooperative, as it provides clear and specified benefits for its members – specifically a set of powers, rights and constraints over the use of their personal health data – in such a way as to also benefit the wider community by providing data for health research. Some of these powers and rights would be provided by GDPR, but Salus is committed to providing them to its members in a transparent and usable way.

Sustainability of the cooperative: Salus has run small-scale studies since 2016, and promotes itself as being about to generate ‘better’ data for research (in relation, for example, to surveys), creating ‘new’ datasets (such as heartbeat data generated through consumer wearables) and ‘more’ data than other approaches. However, the cooperative’s approach to sustainability is unclear. In June 2021, it aims to publicly launch CO3 (Cooperative COVID Cohort), a project stream to help COVID-19 research,44 and it aims to capture a fraction of the value generated by providing data for researchers to sustain itself.

2. Driver’s Seat

Driver’s Seat Cooperative LCA (‘Driver’s Seat’)45 is a driver-owned cooperative incorporated in the USA in 2019,95 with ambitions to help unionise or collectivise the gig economy. It helps gig-economy workers gain access to work-related smartphone data and get insight from it:

it is ‘committed to data democracy … [and] empowering gig workers and local governments

to make informed decisions with insights from their rideshare data.’

The Driver’s Seat app, available only in the US, allows on-demand drivers to track the data they generate, and share it with the cooperative, which can then aggregate and analyse it to produce wider insights. These are fed back to members, enabling them to optimise their incomes. Driver’s Seat Cooperative also collects and sells mobility insights to city agencies to enable them to make better transportation-planning decisions. According to the website, when ‘the Driver’s Seat Cooperative profits from insight sales, driver-owners receive dividends and share the wealth’.

One issue here, unexplored on the website, is that in the ride-hailing market, in geographically limited areas, drivers may indeed have common interests, but they are also in competition with each other for rides. Access to data could also open up job allocation to scrutiny, something that is concerning drivers in the UK, where a recent complaint against Uber has been brought by drivers who want to see how algorithms are used to determine their work, on the basis that this could be allowing discriminatory or unfair practices to go unchecked.46

Governance: Driver’s Seat Cooperative is an LCA or Limited Cooperative Association in the US, so will be governed by the legislation and rules associated with this type of entity. It is not obvious from the website what the terms and conditions are for becoming a member of the cooperative and how it is democratically controlled.

Data rights: Driver’s Seat is headquartered outside the jurisdiction of the GDPR. A detailed privacy notice sets out how Driver’s Seat collects and processes personal data from its platform, which includes its website and the Driver’s Seat app.47 By accessing or using the platform the user consents to the collection and processing of personal data according to this notice.

Sustainability of the cooperative: Driver’s Seat is a very new cooperative and a graduate of the 2019 cohort of the start.coop accelerator programme in the US.48 PitchBook reports that it secured $300k angel investment in August 2020.49 According to its website, Driver’s Seat sells mobility insights to city agencies, which is doubtless at least part of its plan for long-term sustainability. It is not obvious from the website if there is any further investment requirement from the driver-owners of the cooperative above and beyond sharing their data. The app itself is free.

3. The Good Data (now dissolved)

The Good Data Cooperative Limited (‘The Good Data’)50 was a cooperative registered in the UK that developed technology

to collect, pool, anonymise (where possible) and sell members’ internet browsing data on their own terms, to correct the power imbalance between individuals and platforms (selling ‘on fair terms’).51 Members participated in The Good Data by donating their browsing data through this technology, so that the cooperative could trade with it anonymously enabling the cooperative to raise funds to cover costs and fund charities.52

As with Salus Coop, The Good Data provided benefits for members while simultaneously promising potential benefits for the wider community (and indeed many of those wider benefits would also be reasons for members to join).

Governance: The Good Data was registered as a cooperative society under the Co-operative and Community Benefit Societies Act 2014, and accordingly was subject to the requirements of that Act and had to be governed according to its rules filed with the FCA. The Good Data determined which consumers should receive the data, and made decisions about what to sell and how far to anonymise on a case-by-case basis. It declined to collect data from ‘sensitive’ browsing behaviour, which included looking at ‘explicit’ websites, as well as health-related and political sites.53 According to The Good Data’s last annual return filed at the FCA,54 The Good Data had three directors. Members had online access to all relevant information and based on that could present ideas or comments in the online collaboration platform at any time. Members could also participate in improving existing services and an Annual General Meeting was held once a year.

Data rights: It is hard to say what rights were invoked here. If the data has been anonymised, it is no longer personal data under the GDPR. If the data is likely to be re-identifiable or to be attributed to an individual, then the data is pseudonymised (and thus still personal data).

Sustainability of the cooperative: Revenue was generated from the sale of anonymised data to data brokers and other advertising platforms, and the profits redistributed, to maintain the system, and for social lending in developing countries. Decisions about the latter were determined by cooperative members. However, the model proved not to be sustainable, as its website announces the dissolution of the cooperative: ‘we thought that the best way to achieve our vision was by setting up a collaborative and not for profit initiative. But we failed to pass through the message and to attract enough members.’ The Request to Cancel filed at the FCA55

also indicated that this was due to Google rejecting The Good Data’s technology, which was intended to allow members to gain ownership of their browsing data from its Chrome Webstore, and being unable to build a new platform to pursue this objective given the required technical complexity and lack of sufficient human and financial resources.

Created with similar intentions, Streamr56 advocates for the concept of ‘data unions’ and seeks to create financial value for individuals by creating aggregate collections of data in a similar way, including focusing on web browser data – it’s unclear whether this effort will prove more sustainable than The Good Data.

Problems and opportunities addressed by data cooperatives

From the examples surveyed above, data cooperatives appear mostly concerned with personal data (as opposed to non-personal data) and, in general, are directed towards giving members more control over data they generate, which in turn can be used to address existing problems (including social problems) or open up new opportunities. This is very much in line with the purpose of the cooperative model generally. For example, Salus Coop allows members to control the use of their health data, while opening up new opportunities for health research. The Good Data was aimed at giving data subjects more control and bargaining power with respect to data platforms, to get a better division of the economic benefits. Unionising initiatives, such as Driver’s Seat, have focused largely but not exclusively on the gig economy, and using data to empower workers and enable them to optimise their incomes and working practices.

Many data cooperatives seek to repurpose existing data at the discretion of groups of people, to create new cooperatively governed data assets. In this respect, they tend to pursue a positive agenda that uses data as a resource. For example, Driver’s Seat brings in data from sources such as rideshare platforms and sells mobility insights based on this data, sharing profits among members. The Good Data’s business model was to trade anonymised internet browsing data. Some data cooperatives do also seek to refactor the relationship between organisations that hold data and individuals who have an interest in it. The Good Data’s technology to collect internet browsing data was also designed to give members using it more privacy by blocking data trackers.

See also RadicalxChange’s proposal in Annex 3, which contains elements of all three legal mechanisms presented in this report. Described as a conceptual model, it would shake up the status quo even more by making corporate access to data subject’s data the cooperative decision of a Data Coalition.

Although privacy is usually a feature they respect, it is hard to find data cooperatives intending to preserve privacy as a first priority, through limiting the data that is collected and processed. Indeed, this is rather a negative aim, constraining the use of data, rather than pursuing a positive agenda and opening up a new purpose for the data.

More often data anonymisation techniques and privacy-preserving technologies are referred to, however these areas require research and investment,57 especially given the legal uncertainty as to what it takes for companies to anonymise data in the light of the GDPR, and the complexity of the task of anonymisation itself, which requires a thorough understanding of the environment in which the data is held.58

Examples that we have surveyed could be said to recognise the balance between 1) complete privacy and 2) the potential benefits to the individual from collecting and processing personal data and communicating the insights to the individual, and 3) in those individuals then being able to better influence the market and receive a better division of the economic benefits (e.g. through selling the data and/or insights).

Challenges

The cooperative approach appeals to a sense of data democracy, participation and fair dealing that may inform and shape the structuring of any data-sharing platform but, in themselves, cooperatives face a number of challenges:

1. Uptake

While the examples we’ve analysed represent experimentation around data cooperatives, there doesn’t appear to be significant uptake and use of them, and little evidence that they will scale to steward significant amounts of data within a particular geography or domain. This is perhaps unsurprising, given a number of challenges to uptake, as cooperatives require motivated individuals to come together and actively participate by:

- recognising the significance of the problem a cooperative is trying to solve (resonance challenge)

- being interested enough to find or engage with a data cooperative as a means to solve the problem (mobilisation challenge)

- trusting a particular cooperative and its governance as the best place to steward data (trust challenge)

- being data literate enough to understand the implications of different access permissions, and/or willing to devote time and effort to managing the process. Because cooperatives presume a role for voluntary members and rely on positive action to function, this is more likely to work in circumstances where all participants

are suitably motivated and willing to consent to the terms of participation (capacity challenge).

The examples surveyed offer some insights into how these elements of the uptake challenge could be met. A strong common incentive could be enough to meet the mobilisation challenge by employing bottom-up attempts to create data cooperatives. For example, Driver’s Seat could use the interest and perceived injustice among gig-economy workers in their working conditions and pay to build an important worker-owned and controlled data asset. If endorsed or even delivered by trusted institutions such as labour unions this could further enhance uptake.

Other examples, such as The Good Data, were aiming to mobilise people around the concept of correcting a power imbalance between individuals and platforms. In a similar vein, the aim of the RadicalxChange model (discussed further in Annex 3) works at the level of power imbalance, with an added requirement for legislative change to make their data coalitions possible and reduce the market failure of data.59

Such a top-down approach could create challenges not too far removed from the issues that many data cooperatives seek to address, such as around the selected default sharing and processing options that the data would be subject to, and the abilities of people to opt-out or switch. Relying on individual buy-in for success may never move the needle, without more of a purpose or affiliation to coalesce around. Changing the world for the better is more abstract and often less motivating than changing one’s particular corner of it for one’s (and others’) benefit.

These uptake challenges are not unique to cooperatives and are experienced by many other data-stewardship approaches that focus on empowering individuals in relation to their personal data. However, potentially, the features of a cooperative approach to data stewardship could themselves hinder the uptake and scalability of a data cooperative

initiative. These are discussed next.

2. Scale

There are additional features of cooperatives that may make this approach unsuitable for large-scale data-stewardship initiatives:

a. Democratic control and shared ownership

The cooperative model presumes shared ownership. The implied level of commitment may be an asset to the organisation, but may similarly make it hard for the model to scale if everyone wants their say.

The cooperative model also favours democratic control. Depending on how the cooperative is established and governed, the democratic control of cooperatives could be too high a burden for all but the most motivated individuals, limiting its ability to scale. Alternatively, where a cooperative has managed to scale, this approach could become too unwieldy for a cooperative to effectively carry out its business in a nimble and timely fashion.

Democracy and ownership also need to be balanced by a constitution. It may aim for equal say for members (one member, one vote), or alternatively it may skew democratic powers toward those members with more of a commitment (e.g. based on the amount of data donated).

Questions need to be resolved about what members vote for – particular policies, or simply for an executive board. Can the latter restriction, which will lead to more efficient decision-making, still enable individual members to feel the commitment to the cause that is needed to meet

the mobilisation challenge? If, on the other hand, members’ votes feed directly into policy, can the cooperative sustain sufficient policy coherence to meet the trust challenge?

b. Rights, accountability and governance

To establish and enforce rights and obligations, a cooperative needs to be able to use additional contractual or corporate mechanisms, and this requires members to engage and understand their rights and obligations. This is particularly important where data is concerned, given legal duties under legislation such as the Data Protection Act 2018, which implements the GDPR in the UK.

Cooperatives can create a large audience of members who can demand accountability and these members may be exposed themselves to personal liability, with associated challenges to manage potential proliferation of claims and fear of unjust proceedings.

Cooperatives may establish high levels of fiduciary responsibility but do not inherently determine particular governance standards or establish clear management delegation and discretion. Registration under the Co-operative and Community Benefit Societies Act 2014

imposes a level of governance that partially echoes the greater body of legislation applicable to registered companies under the Companies Acts. Registration as a company under the Companies Acts will import a broader array of governance provisions.

With respect to data, governance is a particularly sensitive requirement, especially as a cooperative scales. If a cooperative ended up holding a large quantity of data, this may become extremely valuable as network effects kick in. The cooperative would certainly need a level of professionalism in its administration to prosper, especially if its mission required it to negotiate with large data consumers, such as social networks. Moreover, the overarching governance of the administrators of the cooperative would need to be addressed. For example, there could be a data cooperative board with each individual having ownership shares in the cooperative based on the data contributed (which in turn would need a quasi-contractual model to define the role of the board and its governance role regarding data use).

Failure of governance may also leave troves of data vulnerable, if the proper steps have not been taken. In one recent incident, a retail cooperative venture in Canada called Mountain Equipment Co-Op was sold to an American private-equity company from underneath its five million members, after years of poor financial performance (losing CAD$11 million in 2019), with the COVID-19 pandemic as the last straw. The board felt that the sale was the only alternative to liquidation, although the decision was likely to be challenged in court.60 This case throws up data issues specifically – does the buyer get access to data

about the members, for example? But the main point is that a data cooperative managing a large datastore effectively and securely might well have to endure significant costs (e.g. for security), and will need a commensurate income.