Regulating AI in the UK

Strengthening the UK's proposals for the benefit of people and society

18 July 2023

Reading time: 84 minutes

About this report

This report is aimed at policymakers, regulators, journalists, AI practitioners in industry and academia, civil society organisations, and anyone else who is interested in understanding how AI can be regulated in the UK for the benefit of people and society.

It contextualises and summarises the UK’s current plans for AI regulation, and sets out recommendations for the Government and the Foundation Model Taskforce.

Our recommendations are based on extensive desk research, two expert roundtables, independent legal analysis and the results of a nationally representative survey. They also build on previous Ada Lovelace Institute research, including the 2021 report Regulate to innovate[1] and extensive analysis and commentary on the EU AI Act.[2] For more information on our evidence base, see the sections below on ‘Methodology’ and ‘Further reading’.

If you would like more information on this report, or if you would like to discuss implementing our recommendations, please contact our policy research team at hello@adalovelaceinstitute.org.

Executive summary

It seems as if discussions about artificial intelligence (AI) are everywhere right now – new and emerging uses of AI technologies are appearing across different sectors and are also implicit in every conversation about present and future societies.

The UK Government has laid out its ambition to make the UK an ‘AI superpower’, leveraging the development and proliferation of AI technologies to benefit the UK’s society and economy, and hosting a global summit in autumn 2023.

This ambition will only materialise with effective domestic regulation, which will provide the platform for the UK’s future AI economy

‘Regulating AI’ means addressing issues that could harm public trust in AI and the institutions using them, such as data-driven or algorithmic social scoring, biometric identification and the use of AI systems in law enforcement, education and employment.

Regulation will need to ensure that AI systems are trustworthy, that AI risks are mitigated, and that those developing, deploying and using AI technologies can be held accountable when things go wrong.

The UK’s approach to AI regulation

While the EU is legislating to implement a rules-based approach to AI governance, the UK is proposing a ‘contextual, sector-based regulatory framework’, anchored in its existing, diffuse network of regulators and laws.[3]

The UK approach, set out in the white paper Establishing a pro-innovation approach to AI regulation rests on two main elements: AI principles that existing regulators will be asked to implement, and a set of new ‘central functions’ to support this work. [4]

In addition to these elements, the Data Protection and Digital Information Bill currently under consideration by Parliament is likely to impact significantly on the governance of AI in the UK, as will the £100 million Foundation Model Taskforce and AI Safety Summit convened by the UK Government.[5] [6] [7]

At the Ada Lovelace Institute we have welcomed the allocation of significant Government resource and attention to AI safety, and its commitment to driving AI safety forward at a global level. It will be important that the definition of ‘safety’ adopted by the Government is an expansive one, reflecting the wide variety of harms arising as AI systems become more capable and embedded in society.

It is also unlikely that international agreements will be effective in making AI safer and preventing harm, unless they are underpinned by robust domestic regulatory frameworks that can shape corporate incentives and developer behaviour in particular. The credibility of the UK’s AI leadership aspirations therefore rests on getting the domestic regime right.

Regulating AI in the UK: our recommendations

Our recommendations fall into three categories, reflecting our three tests for effective AI regulation in the UK: coverage, capability and urgency.

Coverage

AI is being deployed and used in every sector but the UK’s diffuse legal and regulatory network for AI currently has significant gaps. Clearer rights and new institutions are needed to ensure that safeguards extend across the economy.

| Challenge | Recommendation |

| Legal rights and protections

New legal analysis shows safeguards for AI-assisted decision-making don’t properly protect people. |

Recommendation 1: Rethink the elements of the Data Protection and Digital Information Bill that are likely to undermine the safe development, deployment and use of AI, such as changes to the accountability framework.

Recommendation 2: Review the rights and protections provided by existing legislation such as the UK General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the Equality Act 2010 and – where necessary – legislate to introduce new rights and protections for people and groups affected by AI to ensure people can achieve adequate redress. Recommendation 3: Publish a consolidated statement of the rights and protections that people can expect when interacting with AI-based products and services, and organisations providing them.

|

| Routes to redress

Even when legal safeguards are in place, accessing redress can be costly and unrealistic for many affected people.

|

Recommendation 4: Explore the value of establishing an ‘AI ombudsman’ to support people affected by AI and increase regulators’ visibility of AI harms as they occur.

|

| Regulatory gaps

The Government hasn’t addressed how its proposed AI principles will apply in many sectors. |

Recommendation 5: Set out how the five AI principles will be implemented in domains where there is no specific regulator and/or ‘diffuse’ regulation and also across the public sector. |

Capability

Regulating AI is resource-intensive and highly technical. Regulators, civil society organisations and other actors need new capabilities to properly carry out their duties.

| Challenge | Recommendation |

| Scope and powers

Regulator mandates and powers vary greatly, and many will be unable to force AI users and developers to comply with all the principles.

|

Recommendation 6: Introduce a statutory duty for legislators to have regard to the principles, including strict transparency and accountability obligations.

Recommendation 7: Explore the introduction of a common set of powers for regulators and ex ante, developer-focused regulatory capability. Recommendation 8: Clarify the law around AI liability, to ensure that legal and financial liability for AI risk is distributed proportionately along AI value chains. |

| Resourcing

AI is increasingly a core part of our digital infrastructure, and regulators need significantly more resourcing to address it. |

Recommendation 9: Significantly increase the amount of funding available to regulators for responding to AI-related harms, in line with other safety-case based regulatory domains.

|

| The regulatory ecosystem

Other actors such as consumer groups, trade unions, charities and assurance providers will need to play a central role in holding AI accountable. |

Recommendation 10: Create formal channels to allow civil society organisations, particularly those representing vulnerable groups, to meaningfully feed into future regulatory processes, the work of the Foundation Model Taskforce and the AI Safety Summit.

Recommendation 11: Establish funds and pooled support to enable civil society organisations like consumer groups, trade unions and advisory organisations to hold those deploying and using AI accountable. Recommendation 12: Support the development of non-regulatory tools such as standards and assurance.

|

Urgency

The widespread availability of foundation models such as GPT-4 is accelerating AI adoption and risks scaling up existing harms. The Government, regulators and the Foundation Model Taskforce need to take urgent action.

| Challenge | Recommendation |

| Legislation and enforcement

New legislation, and more robust enforcement of existing laws, will be necessary to ensure foundation models are safe. |

Recommendation 13: Allocate significant resource and future parliamentary time to enable a robust, legislatively supported approach to foundation model governance as soon as possible.

Recommendation 14: Review opportunities for and barriers to the enforcement of existing laws – particularly the UK GDPR and the intellectual property (IP) regime – in relation to foundation models and applications built on top of them. |

| Transparency and monitoring

Too often, foundation models are opaque ‘black boxes’, with limited information available to the Government and regulators. |

Recommendation 15: Invest in pilot projects to improve Government understanding of trends in AI research, development and deployment.

Recommendation 16: Introduce mandatory reporting requirements for developers of foundation models operating in the UK or selling to UK organisations. |

| Leadership

Priorities for AI development are currently set by a relatively small group of large industry players. |

Recommendation 17: Ensure the AI Safety Summit reflects diverse voices and an expansive definition of ‘AI safety’.

Recommendation 18: Consider public investment in, and development of, AI capabilities to steer applications towards generating long-term public benefit.

|

Introduction

In response to the proliferation of new and emerging artificial intelligence (AI) uses across business sectors, the UK Government has laid out its ambition to make the UK an ‘AI superpower’, leveraging the development and proliferation of AI technologies to benefit the UK’s society and economy.[8]

This can’t happen without effective regulation, which provides the platform on which the UK’s future AI economy can be built. ‘Regulating AI’ means addressing issues that might harm public safety and trust in AI, such as data-driven or algorithmic social scoring, biometric identification and the use of AI systems in law enforcement, education and employment. In other words, making those developing, deploying and using AI systems accountable for the significant impact those systems have on our lives and on society.

Done properly, this accountability should be a prerequisite rather than an impediment to the development of a flourishing UK AI ecosystem. As AI systems become more complex and capable – and as a greater variety of organisations aspire to develop, deploy and make use of them – the existence of clear regulatory rules and a well-resourced regulatory ecosystem can help to provide assurance that these systems are safe and fit for purpose.

Essential to the design of regulatory solutions will be maintaining broad participation and a vision for how AI will benefit society – involving people, particularly those most affected, in the development of these systems. This encompasses access to AI technologies, redress mechanisms if harms occur, and enjoyment of their benefits. Regulation will need to be carefully designed to avoid entrenching the power of existing players – in an already consolidated digital landscape[9] – and to create space for the UK to be competitive.

Box 1: What do the public want from AI regulation?

In June 2023 the Ada Lovelace Institute published the results of a nationally representative survey of UK public attitudes to 17 types of AI-powered technologies.[10]

The survey found that most members of the British public are concerned about risks from a broad range of AI systems, including those that contribute to employment decisions, determine welfare benefits, or even power in-home devices and can infringe on privacy. Concerns cited ranged from the potential for AI to worsen transparency and accountability in decision-making to the risk of personal data being shared inappropriately.

The majority of people in Britain support regulation of AI to mitigate these risks.[11] When asked what would make them more comfortable with AI:[12]

- 62% said they would like to see laws and regulations guiding the use of AI technologies

- 59% said that they would like clear procedures in place for appealing to a human against an AI decision

- 56% want to make sure that ‘personal information is kept safe and secure’

- 54% want ‘clear explanations of how AI works’.

When asked about who should be responsible for ensuring that AI is used safely, people most commonly choose an independent regulator, with 41% in favour. Support for this differs somewhat by age, with 18–24-year-olds most likely to say companies developing AI should be responsible for ensuring it is used safely (43% in favour), while only 17% of people aged over 55 support this.[13]

AI regulation in the UK

There is currently no holistic body of law governing the development, deployment or use of AI in the UK. Instead, developers, deployers and users abide by the existing fragmented network of rules under the UK regulatory ecosystem. This includes ‘horizontal’ cross-cutting frameworks, such as human rights, equalities and data protection law, and ‘vertical’ domain-specific regulation, such as the regime for medical devices.

Numerous examples of non-statutory guidance exist from the Government, regulators, corporate bodies, trade unions and other civil society organisations, covering the relationship between AI and these disparate topics.[14] These initiatives have provided elements of governance, but the landscape for individuals and organisations developing, deploying and using AI in the UK is complex and lacks coherence. This increases both risks and the cost of compliance for businesses, disincentivising AI adoption. It also increases the chance that AI systems might fail, or be misused, in ways that harm individuals or society as a whole.

To address this the Government has signalled its intention to begin the development of a more comprehensive regulatory framework for AI. In 2023 alone it has published a consultation on a policy paper – A pro-innovation approach to AI regulation,[15] begun to assemble a £100m Foundation Model Taskforce,[16] and announced that Britain will host a global summit on AI Safety.[17] Box 2 provides more information on the UK’s journey towards comprehensive AI regulation.

The Ada Lovelace Institute has welcomed these announcements as a sign of the UK’s engagement with the difficult regulatory challenge of governing AI. The Government has adopted several recommendations set out in our report Regulate to innovate, such as the introduction of domain-neutral statutory rules for AI systems for implementation by regulators, and the creation of new central functions to oversee and support this process.[18]

These initiatives will shape the UK’s – and potentially the world’s – approach to AI governance for years to come, and so getting them right matters. We have analysed the Government’s proposals closely to understand whether they will achieve these aims. Drawing on extensive desk research, workshops with experts from across industry, civil society and academia, and independent legal analysis from law firm AWO,[19] the remainder of this report outlines the Government’s plans and puts forward recommendations for how they can be improved.

Box 2: The UK’s journey towards comprehensive AI regulation

The UK Government’s policy paper published in March 2023, and the subsequent announcements of the Foundation Model Taskforce and AI Safety Summit, are only the latest developments in the UK’s journey towards the more comprehensive regulation of AI systems. So far this journey has included:

- the 2017 publication of ‘Growing the artificial intelligence industry in the UK’, an independent review commissioned by government and carried out by Professor Dame Wendy Hall and Jérôme Pesenti[20]

- the establishment in 2018 of the AI Council to advise the Government on AI policy and ethics[21]

- the passage in 2018 of the Data Protection Act, which transposed the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) into UK law

- the publication in 2021 of the National AI Strategy, which outlines the Government’s vision for the development of AI in the UK[22]

- the publication in July 2022 of a policy statement ‘Establishing a pro-innovation approach to regulating AI’ which outlined the broad contours of the UK Government’s proposed approach[23]

- the publication in March 2023 of a policy paper A pro-innovation approach to AI regulation, which laid out the Government’s approach in greater detail[24]

- the announcement in April 2023 of a £100 million Foundation Model Taskforce to be chaired by technology investor Ian Hogarth, with a mandate to ‘lead vital AI safety research’ and replace the AI Council’s advisory functions following the latter’s disbandment at the end of its five-year term[25]

- the announcement in June 2023 that the UK will host a global summit on AI safety in autumn 2023.[26]

The UK Government’s proposals for AI regulation

While the EU takes a primarily rules-based approach to AI governance, the UK is proposing a ‘contextual, sector-based regulatory framework’, anchored in institutions and this diffuse network of existing regulatory regimes.[27] [28]

The UK approach rests on two main elements: AI principles that existing regulators will be asked to implement, and a set of new ‘central functions’ to support them to do so.

In addition to these elements, the Data Protection and Digital Information Bill currently under consideration by Parliament is likely to significantly impact on the governance of AI in the UK, as will the Foundation Model Taskforce and AI Safety Summit convened by the Government.

The Government also expects non-regulatory tools such as standards and assurance to play a role alongside regulation in improving AI outcomes. It has committed to collaboration with partners such as the UK AI Standards Hub to develop these tools and support responsible innovation.[29]

The AI principles

The Government’s March 2023 policy paper A pro-innovation approach to AI regulation sets out five principles, modelled loosely on those published by the OECD:[30]

- Safety, security and robustness

- Appropriate transparency and explainability

- Fairness

- Accountability and governance

- Contestability and redress

The Government intends for these principles to be interpreted and acted on by existing regulators – such as the Financial Conduct Authority in the finance sector, and the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency in the pharmaceutical sector – to ‘guide and inform the responsible development and use of AI in all sectors of the economy’.

They are effectively instructions to regulators about what outcomes they should be aiming for when AI is deployed in the areas for which they are responsible. The principles will not – initially – be placed on a statutory footing, and so regulators will have no legal obligation to take them into account, although the Government has said it will consider introducing a ‘duty to have regard’ to the principles.

The central functions

The Government has also signalled its intention to establish central, cross-cutting functions within government to support regulators in enacting the principles. These are intended to provide cross-cutting support to regulators by creating a common understanding of AI risks, foresight of future developments, better coordination and other mechanisms for improving regulatory capacity.

The central functions will include:

- monitoring and evaluation of the overall regulatory framework’s effectiveness and the implementation of the principles

- assessing and monitoring risks across the economy arising from AI

- conducting horizon scanning and gap analysis, including by convening industry, to inform a coherent regulatory response to emerging AI technology trends

- supporting testbeds and sandbox initiatives to help AI innovators bring new technologies to market

- providing education and awareness to businesses and citizens

- promoting interoperability with international regulatory frameworks including horizon scanning and risk assessment, coordination, and monitoring and evaluation of the overall regime.

The intention is that these ‘central support functions’ will initially be provided from within Government, but they will make use of activities and expertise from regulators and other organisations. The new functions will not replace the work undertaken by regulators and will not amount to the creation of a new AI regulator.

Box 3: How is AI being regulated in other parts of the world?

Outside the United Kingdom, other jurisdictions are developing regulation for the development and use of AI.

The European Union has proposed the Artificial Intelligence Act (AI Act), which is likely to become law in 2024.[31] The Act is a comprehensive piece of legislation aimed at ensuring AI is safe and beneficial. This law employs a risk-based approach and sets different regulatory requirements according to how dangerous a particular AI technology can be. There are three categories of risk:

- Unacceptable risk: These are AI applications that could cause harm or encourage destructive behaviour. These applications are banned outright.

- High risk: These are AI applications in sensitive sectors like healthcare or transportation. They must adhere to strict requirements on transparency, oversight and accountability.

- Low-to-minimal risk: For other AI applications, the rules are less stringent, but there are still requirements around safety and user protection.

For more information on the European AI Act, you can read the Ada Lovelace Institute’s extensive research in this area.[32]

Canada, through its proposed Artificial Intelligence and Data Act, takes a similar approach to the European Union.[33] Canada will not ban any AI applications outright and will instead require AI developers to establish mechanisms that minimise risks and improve transparency, ensuring AI applications respect anti-discrimination laws and that their decision-making processes are clear.

Brazil’s Senate has put forward a draft AI regulation that also has clear parallels to the approach of the EU AI Act.[34]

The United States has yet to propose a nationwide AI regulation. However, the government has issued a ‘Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights’ – a set of non-binding guidelines to promote safe and ethical AI use.[35] These guidelines include better data privacy and protections against unfair decisions by AI systems. At the same time, individual states and city authorities are developing their own AI regulatory measures.

China has enacted many AI relevant regulations since 2021, including a law for personal data protection, an ethical code for AI and most recently guidelines on the use of generative AI.[36] Chinese laws grant users transparency rights to ensure they know when they interact with AI-generated content and the option to switch off AI recommendation services. Measures against ‘deepfakes’ – AI-generated content that is realistic but false – are also in place. However, many of the existing laws only apply to private companies that use AI and not to the Chinese state.

Other major economies, like Japan, India and Australia have issued guidelines on AI but have yet to pass any AI-specific legislation.[37] [38] [39]

The UK GDPR and the Data Protection and Digital Information Bill

The UK GDPR – the legal framework for data protection currently in force in the UK – provides protections that are vital to protecting individuals and communities from potential AI harms.[40] The Data Protection and Digital Information Bill (No. 2), tabled in its current form in March 2023, significantly amends these protections.[41]

The Data Protection and Digital Information Bill is a deregulatory proposal that is intended to reduce the burden on businesses of complying with data protection law. It expands the legal bases for data collection and processing, removes requirements such as the obligation to carry out data protection impact assessments when high- risk processing is being carried out, and weakens protections currently enjoyed by individuals.

A particularly important safeguard in the context of AI is Article 22 of the UK GDPR, which currently prohibits organisations from making decisions about individuals with ‘legal or similarly significant’ effects based solely on automated processing, with a handful of exceptions.

The Bill removes the prohibition on many types of automated decision, instead requiring data controllers to have safeguards in place, such as measures to enable an individual to contest the decision – which is, in practice, a lower level of protection.

The reliance of the Government’s proposed framework on existing legislation and regulators makes it even more important that underlying regulation like data protection governs AI appropriately. Legal advice commissioned by the Ada Lovelace Institute (see below) suggests that existing automated processing safeguards may not in practice provide sufficient protection to people interacting with everyday services, like applying for a loan.

Taken collectively, the Bill’s changes risk further undermining the Government’s regulatory proposals for AI. We discuss this at greater length in the section below on Coverage.

The Foundation Model Taskforce and AI Safety Summit

Two further, recent Government initiatives are set to impact the way AI is governed in the UK.

The first of these is the announcement, first made in April 2023, of a Foundation Model Taskforce, modelled on the Covid-19 Vaccine Taskforce and supported by £100 million of public funding.[42] Led by tech investor Ian Hogarth, the remit of the Taskforce is to lead research into ‘AI safety’.

The second is the announcement, made in June, of a global AI Safety Summit to be held in the autumn and hosted by the UK. [43] The Government intends for this Summit to bring together ‘key countries, leading tech companies and researchers’ to agree on approaches for evaluating, monitoring and mitigating AI risks.

At the Ada Lovelace Institute we have welcomed the commitment of significant Government resource and attention to these important issues. We consider the focus on AI safety is positive, although it will be important to define this term broadly, as discussed in Box 4.

It will also be vital to ensure that the significant investment represented by the Taskforce and AI Safety Summit complements and builds on existing work on AI governance in the UK. The Government’s commitment to driving AI safety forward at a global level is an admirable one, but international agreements will only be effective if underpinned by robust domestic regulatory frameworks that can effectively shape corporate incentives and developer behaviour.

The credibility of the UK’s AI leadership aspirations therefore rests on getting the domestic regime right, and this should be a core element of the Taskforce’s work programme.

Box 4: Defining ‘AI safety’

The Foundation Model Taskforce has been given a mandate to look at ‘AI safety’, which is also the focus of the AI Safety Summit announced by the UK Government. What does it mean for an AI system to be ‘safe’?

AI safety is not an established term and can be interpreted in many different ways. When we talk about safety in other regulatory contexts, we can be referring to anything from food and product safety, road safety, to civil nuclear safety, cybersecurity or online safety.

We think that AI safety should mean keeping people and society safe from the range of risks and harms that AI systems cause today – helping to mitigate those harms, and providing appropriate redress and contestability when they do occur. Broadly, AI harms can be grouped into four broad categories:

- accidental harms arising from AI systems failing, or acting in unanticipated ways, such as self-driving car crashes, or discrimination when sifting job applications

- harms arising from the misuse of AI systems, such as the practice of bad actors generating misinformation using ‘generative’ AI applications such as ChatGPT and Midjourney

- structural harms arising from AI systems altering the dynamics of social, political and economic systems, such as the potential for jobs to change or be significantly altered as a result of AI automation or augmentation, or the aggregate effect of misinformation on democratic institutions

- upstream harms arising further up the AI value chain, such as poor labour practices, negative environmental impacts, and the inappropriate collection or use of personal data or protected intellectual property.

In some cases these harms are common and well-documented[44] – such as the well-known tendency of certain AI systems to reproduce harmful biases – but in others they may be unusual and speculative in nature. Some commentators have argued that powerful AI systems may pose extreme or ‘existential’ risks to human society, while others have condemned such claims as lacking a basis in evidence.

At the Ada Lovelace Institute, we contend that this current polarisation masks a more reassuring conclusion – that the set of solutions for both will stem from the same institutional capabilities, particularly the ability for regulators to look ‘upstream’ at AI developers. It will be important for the definition of ‘AI safety’ used by the Government, the Foundation Model Taskforce and the AI Safety Summit to be an expansive one, reflecting the wide variety of harms that are arising as AI systems become more capable and embedded in society.

Meeting the challenge of regulating AI

The success or otherwise of the UK’s approach to AI regulation will be judged on how effective it is at addressing AI harms, and – in the event that they occur – ensuring that those affected can seek appropriate redress or contestability. The Government’s chosen mechanism for this is the AI principles, which – if implemented effectively – will help to deliver these outcomes.

Our research has identified three ‘tests’ that will determine their success:

- The first is coverage – whether or not the principles are implemented properly across the entire economy. The diffuse legal and regulatory network that the AI principles rely on currently has significant gaps, which would leave AI only partially regulated in certain contexts.

- The second is capability – whether or not the regulatory ecosystem has the appropriate powers and resources needed to give effect to the principles. Regulators, civil society organisations and other actors are not fully equipped at present to tackle the unique social and technical challenges thrown up by AI.

- The third is urgency – whether or not the principles will be embedded rapidly enough to deal with existing and rapidly emerging risks. By the time the UK has set up the first version of its framework for AI regulation in mid-2024, new and risky AI models will be well-integrated into everyday products and services, and entrenched bad practices will be more difficult to fix.

The remainder of this report provides further detail on these tests and sets out 18 recommendations for how the UK Government, regulators and the Foundation Model Taskforce can meet them.

Coverage – protections that extend across the economy

AI harms can occur across the economy, and the mitigations afforded by the AI principles should extend across the whole economy too. We are concerned, however, that the coverage of the regulatory system as proposed by the Government will be uneven.

The Government’s proposed framework devolves implementation of the AI principles to existing regulators, with the support of ‘central functions’. However, there are many contexts in which AI is being deployed that are not comprehensively covered by regulators at present.

In these cases, it is unclear who – if anyone – would be responsible for implementing the principles. These gaps exist because there is limited overlap between the domains where the UK has historically developed regulatory oversight, and those where AI use presents significant risks.

Some sectors – such as financial services, or pharmaceuticals – are already comprehensively regulated, with well-resourced regulatory bodies that are able to shape organisational practices through effective enforcement and the setting of incentives.

In these sectors it is plausible that regulators will integrate the AI principles into existing ex ante regulatory mechanisms, helping to mitigate AI harms. There are also likely to be free-to-use ombudsman schemes in these sectors – such as the Financial Ombudsman Service[45] – that provide an effective and accessible mechanism for applicants to seek ex post remedies when necessary.

Gaps in coverage

Large swathes of the UK economy are currently unregulated or only partially regulated. It is unclear who would be responsible for implementing AI principles in these contexts, which include:

- sensitive practices such as recruitment and employment, which are not comprehensively monitored by regulators, even within regulated sectors

- public-sector services such as education and policing, which are monitored and enforced by an uneven network of regulators

- activities carried out by central government departments, which are often not directly regulated, such as benefits administration or tax fraud detection

- unregulated parts of the private sector, such as retail.

In these contexts, there will be no existing, domain-specific regulator with clear overall oversight to ensure that the new AI principles are embedded in the practice of organisations deploying or using AI systems.

Independent legal analysis commissioned by the Ada Lovelace Institute [46] has found that in these contexts, relevant ex ante regulation applicable to AI is limited to cross-cutting areas of law such as the UK GDPR and the Equality Act.[47] Relevant ex post regulation would be provided by the UK GDPR, which offers potential routes to challenge the processing of personal data.

Box 5: Independent legal analysis of the Government’s proposals

Following the publication of the Government’s policy paper on AI regulation and the revised version of the Data Protection and Digital Information Bill, the Ada Lovelace Institute commissioned law firm AWO to carry out independent analysis of the Government’s plans.

We asked AWO to consider three scenarios in which the use of AI could result in unintended harms. These were:

- the use of an AI system to manage shifts in a workplace

- the use of an AI system to analyse biometric data as part of a mortgage application

- the deployment of an AI chatbot, based on a foundation model, by the Department of Work and Pensions to provide advice to benefits applicants.

For each of these scenarios, we asked AWO to provide an overview of the safeguards that would be in place to protect individuals from harm, or ensure they could access appropriate redress and contestability, assuming that the Government’s proposals were implemented and that the Data Protection and Digital Information Bill was passed in its current form.

The table below indicates the level of legal protection that AWO identified in each sector.[48]

Table 1: Summary of legal protections against AI harms in three sectors (Employment, Financial Services, and Benefits Provision). Reproduced from forthcoming legal analysis commissioned by Ada

| Are there legal requirements that the decision-maker must consider in advance? | Is it likely that a regulator would prevent the AI harm through enforcement of those requirements? | Would the individual be able to find out about and evidence the harm? | Is there a legal right to redress for the harm? | Is it practical for individuals to enforce any legal rights to redress? |

| Scenario 1: Employment | ||||

| Limited: The UK GDPR and Equality Act impose some requirements, but these do not address all the harms in the scenario or fundamentally prevent the tool from being used. | Unlikely: relies on enforcement by the ICO and the EHRC, both of which are limited in the information available to them, their powers and enforcement approach, and their resources. | Low/medium:

Some additional protections from ERA in relation to statements of pay. |

Medium: GDPR and Equality Act give rise to causes of action for some harms in the Scenario (but not those relating to general working conditions).

Additionally, some harms covered by the Employment Rights Act where an employee is dismissed. |

Impractical: requirement to bring a civil claim for GDPR breaches.

Employment Tribunal for ERA and Equality Act breaches. But this relies on having a protected characteristic and/or employment status, and does not protect against diminished working conditions. |

| Scenario 2: Biometric mortgage assessment | ||||

| Medium: both cross-cutting (GDPR and Equality Act) and sector-specific FCA Rules are relevant to the tool, suggesting it may not be permissible to implement it in the way described. | Medium: reason to believe FCA is a more effective ex ante regulator, as it is focused on one sector and has strong enforcement powers

Super-complaints may also bring issues to the FCA’s attention |

Poor: it would be especially difficult for an individual to identify the harm in this scenario given the opacity of the algorithmic logic, even taking into account GDPR transparency rights. | Good: as well as GDPR and Equality Act causes of action, able to seek redress under FCA rules. | Practical: Financial Services Ombudsman provides free-of-charge resolution with need for legal representation |

| Scenario 3: Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) chatbot | ||||

| Low: the UK GDPR likely does not rule out the use of the tool. Further, any additional guidance for public bodies on the use of AI is non-binding and compliance with the guidance is not monitored. | Very unlikely: relies solely on enforcement by the ICO, which takes a light-touch approach to regulating public bodies, which arguably reduces incentives for compliance. | Poor: relies on non-binding guidance on the part of the DWP and GDPR transparency, which does not require explanations of automated decisions in situ. | Medium: beyond GDPR rights, voluntary DWP maladministration scheme and rights to appeal benefit decisions

But the DWP scheme may not fully compensate consequential losses. |

Practical: appeal from DWP scheme plus option to appeal to Parliamentary Ombudsman. |

Moreover, when the appropriate protections are in place, proactive enforcement has tended to be rare due to – among other factors – the scale of the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO)’s mandate relative to its resources, and the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC)’s lack of enforcement powers. AWO’s analysis found that:

‘It is not realistic to expect the ICO and EHRC as cross-cutting regulators to enforce the UK GDPR and EA with a completeness that will reliably protect against AI harms. They do not have sufficient powers, resources, or sources of information. They have not always made full use of the powers they have.’[49]

This enforcement gap frequently leaves individuals dependent on court action to enforce their rights, which is costly and time consuming, and often not an option for the most vulnerable. At a recent workshop hosted by the Ada Lovelace Institute, expert voices from civil society highlighted that because of the under-resourcing of courts and tribunals – and the resultant backlogs – tools for redress are often beyond the reach of the public. This makes the task set for regulators by the White Paper of ensuring the provision of routes to contestability or redress for AI-related harms significantly harder.

Box 6: Regulating biometrics

Biometric data is uniquely personal. It captures our faces, fingerprints, walking style (gait), tone of voice, expressions and all other data derived from measures of the human body. It underpins many cutting-edge AI technologies such as facial recognition, ‘emotion detection’ and video manipulation such as ‘deep fakes’.

The Ada Lovelace Institute has conducted extensive research on the governance of biometrics in the UK, including:

- an independent legal review of the governance of biometrics in England and Wales led by Matthew Ryder QC.[50]

- the Citizens’ Biometrics Council, a demographically diverse group of 50 members of the UK public convened to understand public expectations around biometrics.[51]

The evidence demonstrates that there is no widespread public acceptance of, or support for, the use of biometrics without conditions, limitations and safeguards – and that the existing legal framework does not effectively provide these. Our report Countermeasures recommended the features needed for an effective biometrics governance system.[52]

Biometrics is one of several areas in which new rights and protections may need to be introduced in order to ensure effective governance of AI in the UK, as suggested in Recommendation 2.

Recommendations to improve coverage

Recommendation 1: Rethink the elements of the Data Protection and Digital Information Bill that are likely to undermine the safe development, deployment and use of AI, such as changes to the accountability framework.

We are concerned to see the Government proceed with plans to deregulate the use of data in the UK through the Data Protection and Digital Information Bill. Against an already-poor landscape of redress and accountability in cases of AI harms, the Bill’s changes will further erode the safeguards provided by underlying regulation.

Among other changes, most elements of the existing accountability framework for personal data use will be required only for ‘high-risk processing’, the approach to automated decision-making will be more permissive, and the ability of the ICO to issue guidance independently of Government will be curtailed.

At a time when cross-economy access to powerful commoditised AI systems is growing, altering these legal protections is a serious misstep that risks undermining the Government’s vision for AI safety and therefore the UK’s credibility as an AI leader. The Government should reconsider the elements of the Data Protection and Digital Information Bill that will make AI less safe for affected people in light of increased AI adoption by businesses and individuals, and the outcomes of the review in Recommendation 2.

Recommendation 2: Review the rights and protections provided by existing legislation and where necessary, legislate to introduce new rights and protections

Legal analysis commissioned by the Ada Lovelace Institute finds people affected by AI-informed decisions lack sufficient protection from harm or ability to get redress when things go wrong under existing legislation.

To support appropriate coverage of the AI principles across all sectors in which AI is likely to be deployed, we urge the Government to review the protections afforded by the UK GDPR and the Equality Act to people and groups affected by AI.

Where necessary, these existing rights may need to be strengthened to ensure an appropriate baseline of protection is available even in unregulated and partially regulated sectors. We have highlighted areas where this is the case, such as the regulation of biometric technologies.

The Ada Lovelace Institute is continuing to investigate how particular areas of law – such as the automated decision-making provisions contained in the UK GDPR and modified by the Data Protection and Digital Information Bill – could be updated for the era of widespread AI deployment. We expect to publish further information on this work later in the year.

Recommendation 3: Produce a consolidated statement of the rights and protections people can expect when interacting with (organisations using) AI

The Government should take steps to provide a clear and consolidated statement of AI rights and protections, ensuring that members of the public have a clear understanding of the level of transparency and protection they should expect when using or interacting with AI systems.

The Government has said that it envisages regulators issuing joint guidance – albeit with the primary function of providing clarity to businesses, not individuals – and this could also be an appropriate mechanism for communicating with the public.

Another model could be the White House Office of Science and Technology’s ‘AI Bill of Rights’.[53] This document does not in itself have any legal standing but acts as a clear signal of the US Government’s intent to act in certain ways when deploying or using AI, and makes explicit some protections that are provided under the US Constitution and existing laws.

Recommendation 4: Explore the establishment of an ‘AI ombudsman’ to support people affected by AI

There is a need for the to provide some sort of redress or dispute resolution mechanism for individuals affected by AI in sectors where no formal mechanisms currently exist.

Adopting an ombudsman-style model could act as a complement to other central functions the Government has set out, supporting individuals in resolving their complaints, directing them to appropriate regulators where this is not possible, and providing the Government and regulators with important insights into the sorts of AI harms people are experiencing, and whether they are effectively securing redress.

Box 7: How would an ‘AI ombudsman’ work’?

Ombudsmen have worked well in other areas such as financial services and maladministration. Their advantage in the context of AI would be providing a single point of contact, with a mandate to represent the individual in their capacity as citizen, consumer or worker, and covering a range of legal angles.

This is in contrast with regulators who are mandated to balance different interests and often take a particular view on questions of law or policy. To operate effectively, an AI ombudsman would require access to sector-specific expertise, and would therefore need to work closely with sector-specific regulators and ombudsmen.

Where businesses trying to embed AI principles in their products and services will have access to the ICO/ Digital Regulation Cooperation Forum (DRCF) Multi-Agency Advisory Service pilot[54] and the proposed AI Sandbox,[55] there is at present no proposed equivalent for citizens trying to understand how to seek redress when they have suffered harm.

We propose an ombudsman pilot, which would represent a relatively modest investment from the Government, but – if successful – could dramatically improve redress for AI harms and the functionality of the framework as a whole.

Recommendation 5: Set out how the five AI principles will be implemented in domains where there is no specific regulator, where there is ‘diffuse’ regulation and across the public sector.

If implemented, Recommendations 1–3 should help to improve the legal safeguards available to people affected by AI, even in unregulated sectors. An AI ombudsman, as set out in Recommendation 4, would also ensure that there are meaningful routes to redress and contestability available to people affected by AI in these sectors. Taken together, Recommendations 1–4 offer a route to achieving the minimum viable standard of protection in instances of AI harm.

However, the vision articulated by the Government’s AI principles sets a higher bar than this. There will also be a need for the Government to clearly articulate how the principles will apply and be implemented, in scenarios where there is no regulator with obvious current responsibility for doing so. This will need to include unregulated sectors, ‘diffusely regulated’ sectors and the public sector.

There are a number of ways that the Government could do this. It could for example expand the remit and functionalities of existing regulators, to ensure that sectors are adequately covered. It could also consider introducing a ‘backstop regulator’ linked to the AI ombudsman, to implement and enforce the AI principles in contexts and sectors that are not comprehensively regulated at present.

Box 8: Regulation in the public sector

The public sector provides essential services that would otherwise be unavailable or unaffordable to many people, and is also responsible for public safety and security. Accordingly, public services are expected to be held to higher standards, for example through the Public Sector Equality Duty and specific provisions within human rights and administrative law.

The wider public sector is typically regulated horizontally via these frameworks, and services like health and social care are subject to specific regulators like the Care Quality Commission. However, there are many aspects of the public sector that do not have specific regulators – for example, benefits and tax administration by central government departments. These services can have significant impacts on people’s lives, and in many of them AI is already being extensively used (e.g. the use of AI in fraud prevention).

It is unclear who will be responsible for implementing the AI principles in these services, and in other areas of the wider public sector such as government procurement. We contend that it will be important for the Government to clarify this, as set out in Recommendation 5.

Capability – an empowered and well-resourced regulatory ecosystem

Regulating AI effectively is a resource-intensive technical challenge. A second key test for UK AI regulation will be whether regulators and other actors involved in making AI accountable – such as civil society organisations and third-party providers of AI assurance services – have the necessary capabilities to discharge their functions.

At the heart of this regulatory ecosystem is of course regulators themselves. The considerable variation in mandates, powers and resourcing of UK regulators will affect their ability to implement the AI principles.

There is a strong possibility that, without new legislation, regulators may be obliged to deprioritise or even ignore the AI principles if they are perceived to be in conflict with their statutory duties. The Government itself has acknowledged this, saying that some regulators have warned they may ‘lack the statutory basis to consider the application of the principles’.

Even when regulators do apply the principles in their sectors, they may not have the powers to do so effectively. Available powers vary significantly across regulators, and without new statutory powers some may be unable to give effect to some principles. For example, as discussed at greater length in our Regulate to innovate report, in order to conduct technical audits of an AI system, regulators will need the ability to access, monitor and audit specific technical infrastructures, code and data underlying a platform or algorithmic system. Yet not all regulators possess the legal power to compel organisations in their domain to publish particular data or provide it to users of their services: education regulators, for instance, notably lack this power.

Beyond statutory powers and responsibilities, regulators will also need significant expertise – notably in technical domains – and new funding to discharge their new AI responsibilities. The Government intends to provide pooled expertise through the central functions. We welcome this commitment – which was a key recommendation of Regulate to innovate[56] – but are doubtful that it will be sufficient unless the cross-cutting and sectoral regulators with responsibility for regulating AI also receive significant new resources.

Many of these organisations are under-resourced and need additional capacity. The ICO and EHRC, in particular, already have disproportionately broad domains compared to their resourcing, and it would be unrealistic to expect them to engage with all the affected sectors as ‘backstop’ regulators without significant new resources being made available.

Outside of central Government and regulators, we contend that it will be important that a range of institutions and organisations across the public, private and third sectors are appropriately supported to develop and use AI responsibly. This will include organisations developing or stewarding standards, providing assurance activities, or otherwise contributing to the ‘ecosystem of inspection’ around AI – which we discuss at greater length in Box 10 below.

It will also include affected persons themselves. We welcome the Government’s commitment to reflect ‘the full spectrum of views and including seldom heard voices from the general public’ and to ‘bring together a wide range of views including industry, civil society groups and academia’ as part of its ongoing monitoring and evaluation of the regulatory framework. To build trustworthy systems, people affected by technologies must be meaningfully involved in the design and delivery of those systems, and in determining and evaluating means of governance and redress.[57]

Civil society organisations (CSOs) – including consumer groups, trade unions, advice-giving bodies such as Citizens Advice, and charities representing vulnerable people and those with protected characteristics – have a crucial role to play in this process. By representing and advocating on behalf of individuals and communities that are not otherwise well represented in policy and regulatory circles, these organisations can support the Government and regulators to identify AI risks and mitigations, and articulate measures needed to support people affected by AI.

The concept of ‘co-governance’ was absent from the White Paper, but in practice effective regulation depends on collaboration between the Government, regulators, and a wide variety of organisations representing users and affected persons.

This is a reality at a national level, where CSOs can speak with a unified voice, and at a localised level, where these organisations can help to hold organisations deploying or using AI to account, support individuals to navigate redress mechanisms, and report incidences of harm. For this reason, we were disappointed to see that initial Government communications on the Foundation Model Taskforce and AI Safety Summit omitted any reference to civil society expertise or participation, and would welcome a commitment to meaningful involvement of these groups.

Recommendations to improve capability

Recommendation 6: Introduce a statutory duty for regulators to have regard to the principles, including strict transparency and accountability obligations

It will be important for a statutory duty to be introduced, mandating regulators to implement the AI principles. However, a statutory duty to merely ‘have regard’ to the principles could be discharged by regulators by simply stating to the Government, or providing minimal evidence, of their consideration in strategy setting.

To be effective in providing regulator engagement with the principles and accountability for their progress in implementing them, a statutory duty would also need to be supported with robust transparency and accountability obligations. These would include a requirement to report progress to Parliament against specified KPIs, and to publish open data that supports monitoring and evaluation of the entire framework in its effectiveness at mitigating AI risks identified by the central risk function.

Where regulators or the central functions identify AI risks that are poorly mitigated or unmanaged by existing regulation, a policy response will be required from Government. The process for the reporting of these risks, and the Government’s consideration and response to them, should be formalised in a notification and reporting process, ideally with some level of public transparency to ensure accountability for responding.

Recommendation 7: Explore the introduction of a common set of powers for regulators, including an ex ante, developer-focused regulatory capability

The Government should consider the case for legislation that would equip regulators with a common set of AI powers that would put them on an even footing in addressing AI. We are aware of ongoing research at The Alan Turing Institute which seeks to map existing regulator powers and identify gaps. This could complement additional work by Government or the Foundation Model Taskforce to identify gaps in relation to foundation models specifically, as set out in Recommendation 14.

One area that should be considered in this regard is the introduction of greater powers to request information of companies developing, deploying or using AI systems, and to compel those organisations to make that information available more widely when appropriate. Box 9 discusses this, and Recommendation 17 on mandatory reporting requirements is also relevant.

Another major gap in the regulatory toolkit is the lack of powers to ensure that organisations developing or selling AI tools adhere to safety requirements. Regulators could in theory bring in ex ante product safety requirements but it is doubtful whether this is currently feasible in practice. Many existing regulators focus on outcomes, meaning – in practice – that they are only equipped to look at technology at the point of use or commercialisation.

AI, and foundation models (like GPT-4) in particular, confound this model of regulation: they are often the building blocks behind specific technological products that are available to the public (like Bing) and sit upstream of complex value chains.[58] This means that regulators may struggle to reach the companies or other actors most able to address AI-related harms, with the potential consequence that responsibility for addressing risks and liability will accrue to the organisation using an AI tool.

Box 9: Transparency powers and obligations

Public attitudes research by the Ada Lovelace Institute and the Alan Turing Institute,[59] as well as by the Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation[60] shows the public have clear expectations around the transparency of AI systems, and that these will be crucial to the perceived trustworthiness of these technologies. A fuller set of transparency obligations (which would need to be supported by additional powers for many regulators, or other legislative incentivisation) would include:

- Stronger transparency powers for (all) regulators that enable them to clearly access, monitor and audit specific technical infrastructures, code and data underlying a platform or algorithmic system, and could include proactive notification to regulators of the development of higher-risk systems.

- Transparency rights that grant individuals access to more meaningful information about decisions and underlying systems (e.g. logic about the specific decision made about an individual) that would strengthen individual’s ability to seek redress in practice, and apply these to both automated and partially automated decision-making.

- Reconsideration of changes to the UK GDPR accountability framework that reduce and de-standardise recording of information relevant for data subjects exercising their transparency rights or seeking redress.

- Further rollout of the Algorithmic Transparency Recording Standard[61] across the public sector.

- Transparency labelling for AI-generated content, including chat/voice-based products or artificially generated content that could deceive content consumers in relation to real-world people and events.

Recommendation 8: Clarify the law around AI liability

A further area where statutory interventions would be useful concerns the potential value for the law governing legal and financial liability. This could ensure that actors within the AI lifecycle who are in the best position to mitigate given AI risks are appropriately incentivised to address them.

While theoretically it may be possible to address this through contract, market dynamics may result in legal and financial risk being passed towards smaller actors who tend to sit at the end of AI value chains (‘AI users’, which can include organisations and members of the public).

From a UK perspective, this dynamic could be a particularly undesirable one: the UK’s comparative strengths in AI tend towards products and services further down the AI value chain (such as in services associated with the deployment and implementation of AI), rather than in upstream activities. There may therefore be an important role for legislation in is clarifying the law around AI liability and potentially redistributing it.

Recommendation 9: Dramatically increase the amount of funding available to regulators for responding to AI-related harms

To ensure that the UK’s regulatory ecosystem has the necessary capabilities to implement the AI principles, the Government should introduce funding for cross-cutting regulators such as the EHRC and ICO to scale up monitoring and enforcement.

AI is a general-purpose technology with significant safety implications, which will increasingly form part of the UK’s digital infrastructure. In other domains where safety and public trust are paramount and where underlying technologies form important parts of national infrastructure – such as civil nuclear, civil aviation, medicines, road and rail – annual regulatory funding is in the region of tens of millions of pounds, if not higher.

Regardless of whether AI regulation is delivered on a centralised or distributed basis, or of the funding model, we contend that the challenge of governing a general-purpose technology like AI effectively will be on a similar scale, and the Government should consider models for providing resourcing accordingly – both for regulators, but also for central Government policy capacity.

We anticipate the needs of digital regulators (such as those that are members of the DRCF) will be different to less-digitally mature regulators, which will have smaller, less-specialist teams of AI-focused experts (if any) and which would benefit more from centralised capacity in the absence of increased ring-fenced AI funding.

Digital regulators could play a significant role in upskilling and sharing learning across the wider regulatory ecosystem through the central functions, as well as building on existing coordination mechanisms such as the DRCF and Regulators’ AI Working Group.

Recommendation 10: Create formal, funded channels to involve civil society organisations, particularly those representing vulnerable groups, meaningfully in the regulatory process, the work of the Foundation Model Taskforce and the AI Safety Summit

One activity that the Government could consider is the provision of formal channels to involve civil society organisations – such as consumer groups, trade unions, and groups representing underrepresented and vulnerable people – in the work of regulators and the central functions. This should include opportunities to meaningfully participate in the work of the Taskforce and the AI Safety Summit. Strategic partnership arrangements between Government and civil society organisations, which have led to significant policy improvements (e.g. in health),[62] could serve as a useful model to follow.

This work would need to be appropriately funded: many civil society organisations are under-resourced, particularly those that provide front-line services or that work with vulnerable communities, and failing to fund participation would risk excluding these perspectives.

Conversely, some civil society organisations are wholly or mostly funded by large private-sector organisations, and in these cases their research or policy positions may not be independent. Providing an even playing field for a diverse array of civil society voices will be crucial to ensuring that civil society participation in the AI governance system is of genuine value rather than becoming an opportunity for regulatory capture.

The Government could seek to draw lessons from the experience of previous initiatives such as Open Banking, which has been praised for having civil society appointees on expert groups but criticised for failing to fund participation.[63]

Recommendation 11: Establish funds and pooled support for civil society participation in all levels of the regulatory process

In addition to formal input at a national level from civil society organisations, the Government should also explore how civil society organisations at a local level can be supported to engage with the regulatory system.

Trade union branches, consumer groups, local community organisations and organisations representing people with protected characteristics are in close contact with those who are likely to be the most affected by AI technologies. As such these organisations will need to play an important role in the regulatory ecosystem: holding organisations deploying or using AI to account, and supporting individuals to navigate redress mechanisms and report incidences of harm to regulators and the AI ombudsman.

As AI systems continue to be integrated into our everyday lives – from schools and workplaces to shops and public spaces – these organisations will require funding and expertise to ensure they can continue to effectively serve their communities.

As such, we contend that the Government should consider introducing ringfenced funding and pooled support to help upskill a diverse range of civil society organisations in AI and resource their meaningful engagement with regulators, the central functions, and the AI ombudsman.

Recommendation 12: Support the development of non-regulatory tools for trustworthy AI

The Government also expects non-regulatory tools such as standards and assurance to play a role alongside regulation in improving AI outcomes. It has committed to collaboration with partners such as the UK AI Standards Hub[64] to develop these tools and support responsible innovation. Box 10 explains these practices at further length.

We believe that supporting the flourishing of an ‘ecosystem of assessment, assurance and audit’ can help to mitigate AI harms. However, we are concerned that this could become a point of failure within the regulatory system if policymakers overestimate the capability of a still-nascent AI assurance market to catch certain risks and drive up standards.

The Government is already supporting the development and adoption of assessment, assurance and audit mechanisms through vehicles like case studies and its support for the AI Standards Hub. We think there are a number of other ways that the Government could support the creation of an effective assessment ecosystem:

- Create incentives for companies, drawing on external expertise and certification where appropriate, to assess risks from AI systems, e.g. mandated algorithmic impact assessments in particular sectors, or introducing requirements as part of data-access processes and procurement requirements in the public sector.

- Introduce domain or sector-specific guidance on societal risks (perhaps produced by regulators) that could support the development of AI risk and impact assessment methods tailored to specific sectors.

- Developing the skills base. The technology sector will need teams, roles and staff with the skills to conduct risk and impact assessments. In particular, many methods involve identifying and coordinating diverse stakeholders, and the use of participatory or deliberative methods that are not currently widespread in the technology sector, but are more established in other domains such as participatory research, policy, design, academic sociology and anthropology.

- Resourcing and empowering organisations to assess risks and impact. Many of the most well-known and significant AI risk assessments to date have been conducted by civil society groups, academics and companies that evaluate a system’s impacts without the permission of the company. However, these organisations often lack access or information about emerging AI systems, and may not be well resourced to conduct these kinds of assessments.

Box 10: Methods for assessing AI risks

With the increasing use of AI systems in our everyday lives, it is essential to understand the risks they pose and take necessary steps to mitigate them. There is not a singular, standardised process for assessing the risks or impacts of AI systems, but there are a number of emerging methods, including:

- audit and regulatory inspection

- independent oversight bodies and ethics review committees

- red teaming

- safety checklists

- model and dataset documentation methods

- transparency registers.

While regulators have a big role to play in assessment of AI systems, a variety of organisations can carry out these activities across the lifecycle of an AI system’s development and deployment. Some of these activities are being proposed in or mandated by legislation, while others are being experimented with by industry on a voluntary basis. Many other organisations, including within civil society, academia and commercial services, will be essential for developing and implementing assessment practices at scale.

For more information on these activities, and how Government and regulators can facilitate them, read the Ada Lovelace Institute’s recent research paper.[65]

Urgency – taking action before it’s too late

The third factor is sufficient urgency on current and emerging risks. The Government envisions a timeline of at least a year before the first iteration of the new AI framework is implemented, with further time needed to evaluate its effectiveness and address any emerging limitations.

Under ordinary circumstances, that would be considered a reasonable schedule for establishing a long-term framework for governing an economically and societally cross-cutting technology. But there are significant harms associated with AI use today, many of which are felt disproportionately by the most marginalised members of society. In particular, the pace at which foundation models are being integrated into the economy and our everyday lives means that they risk scaling up and exacerbating these harms.

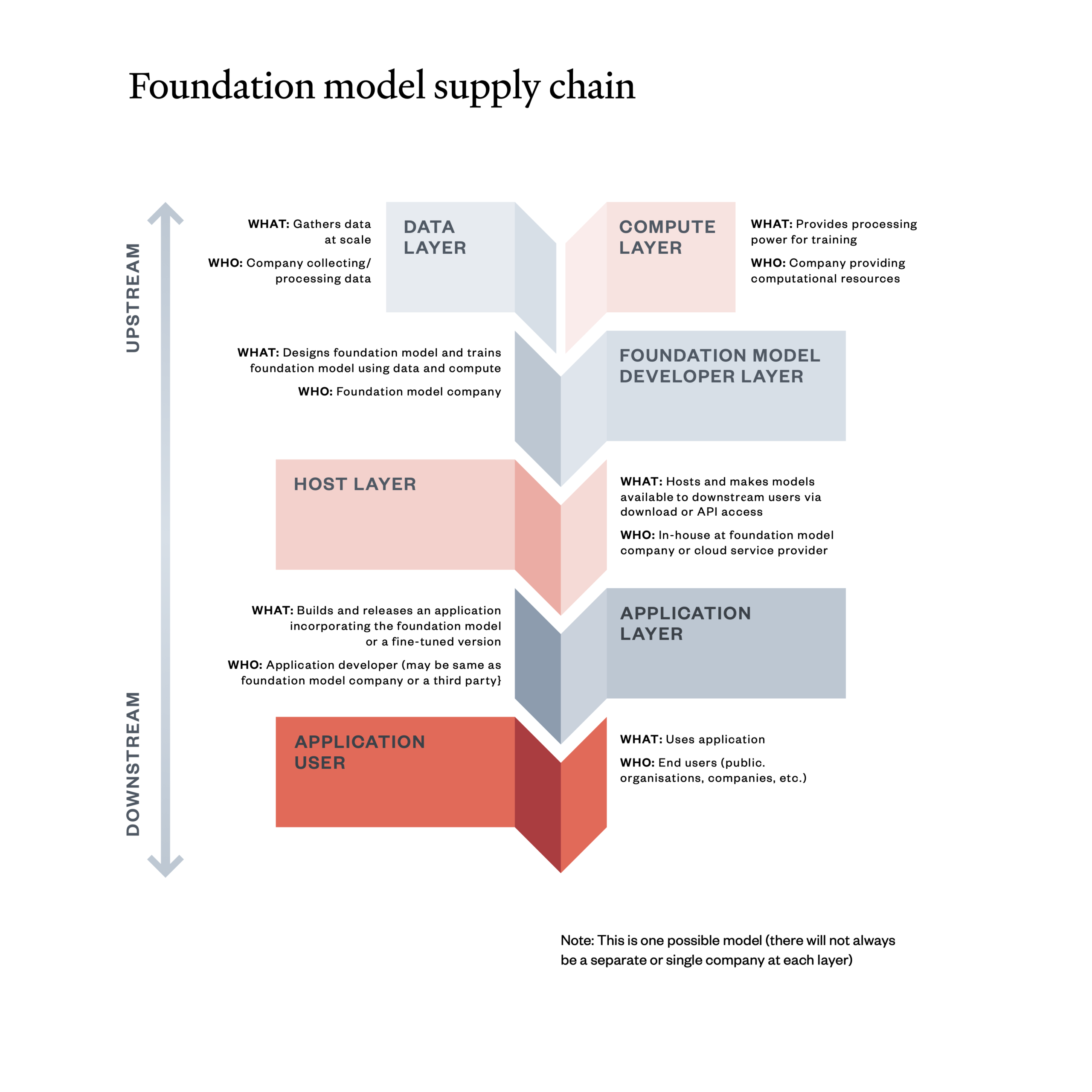

Foundation models, sometimes called ‘general-purpose AI’ or ‘GPAI’, are powerful AI systems that are capable of a range of general tasks (such as text synthesis, image manipulation and audio generation). The most prominent examples are OpenAI’s GPT-3 and GPT-4, foundation models that underpin the conversational chat agent ChatGPT. Our explainer on foundation models[66] provides more in-depth discussion of the various terms used to describe foundation models, and how they can be used.

Because foundation models can be built on to develop different applications for many purposes, this makes them difficult – but necessary – to regulate, as discussed in Box 11 below. When foundation models are used as a base for a range of applications, any errors or issues at the foundation-model level may impact any applications built on top of or ‘fine-tuned’ from that model.

Foundation models are already being used to add novel features to applications ranging from search engines (like Bing) and productivity software (like Office365) to language learning tools (such as Duolingo Max) and video games (such as AI Dungeon). In some cases they are available through widely available application programming interfaces (APIs), which enable businesses to integrate them into their own services. This widespread availability means that they can be integrated into products, services and organisational workflows more easily than many other types of AI.

This unchecked distribution of foundation models risks compounding the challenges of embedding the AI principles in the practices of organisations deploying and using AI. Timely action from the and the Foundation Model Taskforce will be necessary to ensure that, as the usage of foundation models grows, these cutting-edge technologies are considered trustworthy by businesses and the public.

Box 11: Governance challenges for foundation models

Foundation models pose many novel regulatory challenges beyond those of other AI systems.

The first of these relates to where foundation models are located in the AI value chain. As discussed above existing regulators focus on outcomes, meaning – in practice – that they’re only equipped or incentivised to look at technology at the point of use or commercialisation.

Foundation models (like GPT-4) are often the building blocks behind specific technological products that are available to the public (like Bing), and themselves sit upstream of complex value chains. This means that regulators may struggle to identify whether a harm from a product is best remedied by the deployer of the tool, or if responsibility should live with the upstream foundation model developer.

Determining which organisations in a value chain are most able to address AI-related harms is a challenge and can create uncertainty around legal liability for negative outcomes. We contend that granting regulators ex ante powers (Recommendation 7) and clarifying liability rules (Recommendation 8) will help to address this.

A second, related challenge concerns market concentration. The capital intensity of frontier AI development, and the reliance of dominant AI approaches on access to huge amounts of data, mean that development of AI systems is predominantly happening in the companies that already hold the majority of power in the digital economy.

Over time, most AI expertise is being acquired by industry: in 2004, only 21% of AI PhDs went to work in industry, by 2020, almost 70% were employed there. It is therefore no coincidence that those at the frontier of developing foundation models and their applications are the same tech platforms who have been dominating the digital ecosystem for the past decade: Google, Microsoft and Meta.

The rise of foundation models may in turn further entrench the existing market power of these global corporations, which could make it difficult for a single, small regulator to challenge – as well as perpetuating wider competition challenges and market harms.

A third challenge is that foundation models tend to be multifunctional, and have the potential to develop greater general capabilities (and thus potential for harm) as they are trained with more data and computing resources. This confounds most approaches to regulation, which centre on particular (sectoral) use cases or products.

Finally, there exists a wide spectrum of different release strategies for foundation models,[67] ranging from fully closed or internal use only to downloadable and fully open source. Models released in a relatively controlled or staged manner may in some respects be easier to govern, whereas open-source models pose challenges in terms of regulatory control and liability.

These challenges are not insurmountable, given sufficient time and resource. We urge the Government to immediately allocate significant resource and future Parliamentary time to enable a robust, legislatively supported approach to foundation model governance as soon as possible (Recommendation 13), as well as taking a number of steps in the immediate term to support better governance of foundation models (Recommendations 14–17).

Recommendations to address urgent risks

Recommendation 13: Immediately allocate significant resource and future parliamentary time to enable a robust, legislatively supported approach to foundation model governance

Foundation models are being integrated into the practices of organisations across the economy. The major factor determining the trustworthiness of foundation models developed or deployed in the UK will be the presence of a strong domestic regulatory framework that can effectively shape incentives and developer behaviour.

We therefore contend that it will be important for the Government to allocate significant resource and future parliamentary time to enable the creation of such a framework. The announcement £100m for the Foundation Model Taskforce chaired by Ian Hogarth is a welcome acknowledgement of this urgency, and Recommendations 14 and 15 make a number of suggestions for how this resource could be fruitfully spent.

It is likely however that certain parts of the solution to foundation model governance will require new primary legislation: for example the introduction of new ex ante powers for regulators (Recommendation 7), clarification to liability rules (Recommendation 8), and mandatory transparency requirements for developers (Recommendation 16). Parliamentary time is a scarce resource, and the Government should act now to ensure that legislation can be passed as swiftly as possible.

Recommendation 14: Review opportunities for and barriers to the enforcement of existing law

We also contend that there is a need to review the opportunities for more proactive enforcement of existing UK law and regulation that addresses the risks of foundation models (notably the UK GDPR, the Equality Act 2010 and the intellectual property regime). At present, the compliance of many widely available foundation models with these legal regimes is questionable.

As discussed in the Capability section above, however, cross-cutting UK regulators are constrained in the powers, resources and the sources of information available to them, as well as cultural barriers to enforcement. There are also particular challenges (as discussed in Box 11 above) associated with enforcing the law in relation to foundation models, chiefly among them the opacity of many widely used models and the datasets used to train them.

The Government – and the Foundation Model Taskforce – could play a constructive role in reviewing these opportunities for, and barriers to, the enforcement of existing law in relation to foundation models. This would strengthen Government understanding of where legislative change might be necessary (Recommendation 13) and what sort of transparency requirements might need to be imposed on developers to facilitate effective regulatory action (Recommendation 16).

Recommendation 15: Invest in pilot projects to improve Government understanding of trends in research, development and deployment