Listening to the public

Views from the Citizens’ Biometrics Council on the Information Commissioner’s Office’s proposed approach to biometrics

18 August 2023

Reading time: 56 minutes

The Citizens’ Biometrics Council views on biometrics governance below relate to the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO)’s proposed guidance on the use of biometric data, which is open for consultation until 20 October 2023.

Foreword

This report represents the views of the Citizens’ Biometrics Council, reconvened in November 2022 to consider the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO)’s proposals for guidance on biometrics. Its publication alongside the publication of the draft guidance,[1] makes a direct connection between people’s views on the use of this emerging and potentially impactful technology, and the opportunity for public voice to inform and shape policy and practice.

Citizens’ councils are used by policymakers to understand public perspectives on issues that affect people and society. The original Citizens’ Biometrics Council in 2020[2] provided insights and context to inform policy decisions on the governance of biometrics, and was published alongside the Ryder Review,[3] an independent legal review of the existing regulatory framework. Government and regulatory interest in these participatory methods is to be commended and should also be accompanied by scrutiny of the extent to which insights and recommendations meaningfully inform policymaking.

The ICO has acknowledged the contribution of the Citizens’ Biometric Council: ‘In developing our guidance, we have sought the views of many stakeholders. The Citizens’ Biometrics Council represent a diverse and engaged group of members of the UK public, who have considered the use of biometrics in great detail. This valuable opportunity to discuss our approach to biometrics, and to see first-hand the views and responses of the public to it, have helped us in framing what the law expects organisations to do when planning to use biometric recognition technologies.’

The reconvened Council provided the ICO with something unique: an expert public panel that already had considerable knowledge and awareness of the potential contexts, benefits and risks of biometric technologies. Participants reflections on the guidance provide detailed recommendations around practicalities of consent, transparency and accessibility, as well as purpose, data collection and storage, and opt-out processes.

They also had high-level concerns: they demonstrated an appetite for new legislation around biometrics, and posed questions as to whether the ICO’s proposed guidance, enforcement powers and capacity would be effective in preventing all unlawful and publicly unacceptable uses of biometric technologies and data. They also articulated clearly the responsibility of ICO to communicate with the public to increase their understanding of data subjects’ rights and organisations’ obligations, as well as raising public awareness of where it has taken enforcement action.

The ICO’s consultation on the draft guidance is the first of a two-part consultation, the first covering data protection and biometric recognition, and the second biometric classification and uses including emotion recognition.

The use of participatory and deliberative methodologies to amplify the voices of people affected by data and AI is key to Ada’s mission to build evidence, convene diverse voices and influence practice and policy. By providing opportunities to amplify and represent the perspectives of excluded, marginalised and underrepresented people, Ada continues to be mindful of our responsibility not just to hear and represent the views of the public, but also to find ways to hold policymakers accountable to them.

Octavia Reeve

Associate Director, Ada Lovelace Institute

Executive summary

In November 2022 the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO), the Ada Lovelace Institute and Hopkins Van Mil worked together to ask members of the Citizens’ Biometrics Council (the Council) for their views on the ICO’s proposed approach to advising on and regulating the use of biometric data.

The Council was established by the Ada Lovelace Institute in 2020, with the support of public dialogue specialists Hopkins Van Mil. It comprises a demographically diverse group of 50 members of the UK public who took part in a deliberative dialogue about biometric technologies and data. To conclude their deliberations, the Council made a series of recommendations in response to the question: ‘What is or isn’t OK when it comes to the use of biometrics?’, which were published in 2021.[4]

As part of the ICO’s work on regulating biometric data, including the drafting of proposed new guidance on biometric technologies and data, they considered the Council’s earlier recommendations. When drafting new guidance on biometric data and biometric technologies, the ICO assessed whether and how it could consider the Council’s recommendations.

In autumn 2022, in partnership with the Ada Lovelace Institute and Hopkins Van Mil, the ICO presented its proposed approach to regulating biometrics to 30 members of the Council for their feedback. During three online workshops and use of an online reflection space, the Council engaged with staff at the ICO, received presentations and information and considered the ICO’s proposals through facilitated, collaborative discussion.

The findings from the Council’s discussions include:

- Overall response to the ICO’s proposals: Council members felt that the ICO had taken strong steps towards addressing the concerns and recommendations they raised in 2020/21, and welcomed the opportunity to engage with their current proposals.

- ‘Teeth’ and effective enforcement: Council members asked questions about whether the ICO’s proposed guidance, enforcement powers and capacity would be effective in preventing all unlawful and publicly unacceptable uses of biometric technologies and data.

- Government and legislation: despite the actions of the ICO and the existing legal framework, many Council members still believed that new legislation around biometrics is necessary to address ethical and societal concerns, and to prevent harm to people and society.

- Public awareness and engagement: Council members noted how there is relatively little awareness among the general public of biometric technologies and data uses, or of the ICO’s actions and powers.

- Consent: consent remained a significant issue for Council members. They worried that the increasing pervasiveness of biometrics in everyday life would diminish opportunities for people to give informed or meaningful consent to the processing of their biometric data. While some reacted positively to the way the ICO intends to include information about consent in its forthcoming guidance, others remained concerned.

- Accessibility and inclusion: Council members raised various concerns about accessibility and inclusion. While several members recognised the potential for biometrics to make services more accessible, others feared that an over-reliance on poorly designed biometric technologies would create more barriers for people who are disabled or digitally excluded.

- Technological change and future uses: the ways biometric technologies might be developed and used in future created unease among some Council members. The ICO’s foresight and horizon-scanning work provided reassurance for some, but others questioned what the ICO could do if it identified a forthcoming use that might be lawful but nevertheless would raise ethical or societal issues.

From these findings, the Ada Lovelace Institute put forward five considerations for the ICO, drawing closely on views expressed by the Council members:

- Guidance as a first step: Broadly, the Council members welcomed the ICO’s proposed guidance for organisations that collect and process biometric data, and saw it as a positive first step towards addressing their concerns. The Council members’ feedback – detailed in the findings in this report – should therefore be used to refine this guidance, and to point towards future action by the ICO or other bodies, such as developing codes of conduct or legal changes. This would ensure biometrics regulation addresses the views expressed during both the November 2022 workshops and the original workshops in 2020.

- Biometric legislation and policy: While directly changing the legislative framework is outside the ICO’s remit and authority, the Council members expressed a desire that the ICO continues to convene and consult with government, industry, academia and civil society as the laws around biometrics and data protection are debated. In doing this, the ICO should advocate for the wants and interests of the public, as evidenced through public participation activities such as these workshops.

- Public engagement and awareness of the ICO: Council members’ comments demonstrate that more ICO-led public engagement and communications would be beneficial. This could include raising public awareness of where the ICO has taken enforcement action, as well as producing a version of the guidance that is accessible to the general public and details data subjects’ rights and organisations’ obligations. It could also include further public dialogue and participation, on biometrics as well as other issues related to the ICO’s work.

- Accessibility and inclusion: through the forthcoming guidance, the ICO could encourage biometrics developers and deployers to ensure their technologies are as widely accessible as possible and that there are alternative mechanisms in place when the use of biometrics poses a barrier, or for those who do not consent.

- Ethical and social concerns: the ICO could further consider how it can address ethical and societal issues related to biometric data use – such as consent, accessibility, categorisation and so on – through its guidance and other activities. For transparency in particular, the ICO could ensure that their forthcoming guidance encourages and supports those developing and deploying biometric technologies to provide clear, plain-English explanations of purpose, data collection and storage, and opt-out processes for data subjects.

In this report, authored by the Ada Lovelace Institute with input from the ICO and Hopkins Van Mil, we detail the background and methodology of the workshops with Council members, and describe and analyse findings from their discussions.

‘I’m feeling positive about how our recommendations have been taken on board but still somewhat apprehensive about how biometric data will be used.’

Council member, November 2022

Introduction

Background: biometrics in 2022

From facial recognition cameras at borders and in job interviews, to voice recognition in smart speakers and keeping bank accounts secure, biometric technologies – and the data they process – are used in an increasing range of settings across society.

Biometric data is information about a person’s unique biological traits such as their face, voice, fingerprint, gait and more. This data can be used to identify an individual, and to attempt to infer other information about them, such as their gender, or their racial or ethnic origin. Proponents of biometrics see benefits in their ability to keep information and people safe and secure and in improving the ways people access services.

However, biometrics also raise several concerns for individuals and society. This includes the increased use of technologies that may permit disproportionate or unjustified surveillance of citizens, and the risk of inaccurate or biased technologies amplifying discrimination against certain groups in society. There are also questions about whether biometrics that aim to categorise a person’s gender or emotions have any empirical validity.[5] [6] [7]

In recent years, as more biometric technologies have been developed and deployed across societies, public debate has grown around the political, legal, ethical and societal questions raised by their use. In the UK, the Data Protection and Digital Information Bill currently in development will ‘make provision about oversight of biometric data’.[8] In the European Union, the forthcoming Artificial Intelligence Act (AI Act) includes articles that will limit and prohibit certain uses of biometrics.[9] In the USA, there is a fragmented regulatory picture, with different states and cities taking different approaches towards biometrics, from prohibitive bans and moratoria through to more permissive legal approaches.[10]

Building evidence about the legal and societal questions raised by biometrics

Against this backdrop, the Ada Lovelace Institute has conducted a three-year programme of research around biometric data and technologies. This included a survey of 4,000 UK adults’ attitudes towards facial recognition, a deliberative dialogue with 50 members of the UK public, and a commissioned independent legal review from Matthew Ryder KC. The conclusions of this programme are detailed in our report Countermeasures, which was published at a launch event at the Royal Society, London, in summer 2022. [11]

Through this research programme, the Ada Lovelace Institute contributed to the evidence base surrounding the legal, ethical and societal questions associated with biometric technologies. Key findings include:

- Our 2019 survey found that there was no widespread public support for the adoption and use of facial recognition, as public acceptability of this technology is highly dependent on context and purpose. In particular, a small majority (55%) wanted the UK Government to limit police use of the technology, and around three quarters of the public were uncomfortable with the use of facial recognition in commercial settings such as supermarkets or hiring processes.[12]

- In the independent legal review of the governance of biometric data in the public sector, Matthew Ryder KC and his team found that ‘the current legal framework is not fit for purpose, has not kept pace with technological advances and does not make clear when and how biometrics can be used, or the processes that should be followed.’[13]

- The members of our 2020/21 Citizens’ Biometrics Council (the Council) developed 30 recommendations in response to the question ‘What is or isn’t ok when it comes to the use of biometrics?’. These recommendations related to developing more comprehensive legislation and regulation for biometric technologies; establishing an independent, authoritative body to provide robust oversight; and ensuring minimum standards for the design and deployment of biometric technologies.[14]

Bringing the ICO and the Citizens’ Biometrics Council together

In response to the active technology and policy landscape around biometrics, the ICO is developing draft guidance for how it, as the UK’s independent regulator for information rights, will approach new and emerging biometric technologies and data uses. An important aspect of the ICO’s approach is engagement with public perspectives, meaning its work on biometrics has closely considered the recommendations made by the Council.

In summer 2022, the ICO partnered with the Ada Lovelace Institute to reconvene the Council – to gather the Council members’ views and feedback on whether their draft proposals adequately addressed the Council’s previous recommendations.

In this report we describe the method of the deliberative workshops conducted with the Council and ICO, the findings from these workshops and considerations for the ICO.

A note on quotes

Throughout this report, any text in quotation marks represents quotes from Council members’ deliberations, drawn from the transcripts of the workshops.

Some quotes have been edited to improve readability, for example by removing repetition or filler words used as Council members articulated their thoughts. There have been no additions, word replacements or other edits that would change their meaning or sentiment.

The quotes have been included to amplify the voices of the Council members and demonstrate the richness of their perspectives.

The value of public participation for technology policy and regulation

New and emerging digital technologies such as social media, virtual reality, biometrics and artificial intelligence raise a dizzying array of legal, ethical and societal questions. Answering those questions is a challenging academic and practical puzzle, as well as a complex political debate laden with contradicting values and ideologies. There are several organisations who face the daunting task of taking action in response to the questions raised by new technologies, and prominent among these are regulators such as the ICO.

One important tool in addressing these questions is public participation, engagement and attitudes research. This can take various forms, from large-scale quantitative surveys to qualitative ethnographic research. The deliberative dialogue approach used in the Citizens’ Biometrics Council draws on established methodologies, which bring informed yet diverse public perspectives to bear on complex policy and societal issues.

These methodologies build understanding of public perspectives, and empower people affected by technology to participate in shaping policy and regulation. Alongside legal analysis, academic research and technological expertise, these approaches are a necessary component in ensuring that new digital technologies work for people and society. This is because, in the view of the Ada Lovelace Institute, public participation and research offers (at least) three things.

- Legitimacy: what gives any organisation the ability to claim that their actions are in the best interests of the public or wider society, if it does not engage with people’s perspectives or values?

- Accountability: public participation provides a mechanism through which an organisation can be accountable to members of the public, by gathering their feedback directly and demonstrating – publicly – how it will address that feedback.

- Evidence: most significantly, public participation helps to address legal, ethical and societal questions of technology, by drawing on lived experience, on crowd wisdom, on deliberative reasoning and on public attitudes. All these provide valuable evidence to understand problems, identify solutions and signal what ‘good’ looks like in the context of data and AI.

How to read this report

…if you’re a policymaker, researcher or regulator concerned with biometric technologies:

- The findings offer insight into the Council members’ thoughts about regulatory action relating to biometrics. These can help to refine activities and strategies relating to the regulation of biometrics data and technologies, in a way that aligns with public perspectives.

- The conclusion outlines five considerations that are relevant for those developing biometrics policy or regulation.

- The boxout below articulates the value of public participation for the development of technology and data policy, and why these findings matter.

- The methods section describes what we did in detail and why, which underpins how we generated robust findings. This may provide helpful insights for those interested in running similar public dialogues or research.

…if you’re a developer or designer building biometric technologies, or an organisation using them:

- The findings summarise the themes that emerged during the Council members’ deliberations about the ICO’s guidance. These are informative for understanding what responsible practices and technology design should look like, and can guide how to build better biometric technologies in line with public perspectives.

- The boxout below articulates the value of public participation for the development of technology and data policy, and why these findings matter.

… if you’re a researcher or public engagement practitioner interested in technology and society:

- The methods section describes what we did in detail and why, which underpins how we generated robust findings. This may be helpful for those interested in running similar public dialogues or research.

- The findings provide insight into public perspectives on biometric technologies and associated regulatory approaches, which contributes to the wider body of evidence around public attitudes towards new technologies.

Methodology

About the Citizens’ Biometrics Council

The Ada Lovelace Institute established the Citizens’ Biometrics Council (the Council) in 2020 with support from public dialogue specialists Hopkins Van Mil, who were commissioned to co-design and deliver the Council.

Taking the form of a ‘deliberative mini public’, the Council comprised 50 members of the UK public, recruited to reflect the diversity of the UK population, with overrepresentation of certain marginalised groups that might be disproportionately harmed by biometric technologies, including people from ethnic groups, disabled people and people who identify as LGBTQ+.

Through a series of in-person and online workshops, Council members reviewed information about biometric technologies and data: what they are, how they work, ways they are used, and the ethical and societal concerns they raise. This was delivered with support from a range of experts from academia, industry, government and policing. They also took part in facilitated conversations, responding to questions and prompts to help them weigh and consider the potential impacts of biometrics – both positive and negative – as well as the ethical and societal implications. Throughout, the Council members collaboratively considered a key question they devised themselves: ‘What is or isn’t ok when it comes to the use of biometrics?’

As the final output, the Council shared a set of 30 recommendations in response to this question. The full method, findings and recommendations can be read in our 2021 report.[15]

Sharing the ICO’s proposals with the Council

Working with Hopkins Van Mil, the Ada Lovelace Institute and the ICO reconvened 30 members of the Council in a series of three online workshops in November 2022, totalling over five hours of facilitated discussion and deliberation.

The aim of these workshops was to gather the views of informed members of the public on the steps the ICO should take to regulate biometric technologies. To help us achieve this aim, Ada and the ICO jointly developed four research questions:

- What are the Council members’ perceptions of biometric technologies, and how have these developed since the last workshops they attended?

- What do members of the Citizens’ Biometrics Council think about the ICO’s proposals and how they respond to issues relating to the governance and regulation of biometrics?

- Do Council members feel that the ICO’s proposals will adequately address their recommendations? If not, are the changes that Council members advocate for within the ICO’s remit?

- What are Council members’ views on issues relating to biometrics that are outside the ICO’s scope and remit?

Re-recruiting Council members

To address the research questions, we brought together 30 members of the original Council. We did not recruit the full 50 members, for several reasons:

- At the time of the workshops in November 2022, it had been almost two years since the Council members had taken part in the process. As a consequence, there would be inevitable ‘attrition’ to the number of available participants.

- Based on the number of participants often included in a widely established deliberative method known as a ‘citizens’ jury’,[16] and enabling representation of a diverse cross-section of the original Council, we aimed to include at least 24 Council members.

- Council members were renumerated £130 for participating in the process. Paying participants for their time is crucial to both enabling people to participate who might not otherwise have the financial means to spend time away from work, as well as to demonstrate the value of their time and expertise. We calculated that 30 participants would be the maximum number possible within the available budget.

HVM sent communications to all of the original Council members, giving them information about the ICO’s interest in gathering their views. Thirty-two people responded positively and we selected 30 Council members who together reflected as diverse a range of demographic backgrounds as possible, based on age, gender, ethnicity, disability, socio-economic background and region.

It is important to note that with such relatively small numbers of people, deliberative mini publics can never be statistically representative of the wider population. However, they can still deliver robust and valid findings. Deliberative mini publics can also be used for a range of purposes. Where the aim is to elicit a broad range of views or perspectives, some methodological experts consider that the best approach is to seek a diversity of demographic backgrounds within the participants, with each person bringing an intersectional breadth of lived experience to the deliberations.[17]

Deliberative workshops

We used a deliberative dialogue methodology for the workshops, similar to the approach taken with the Council in 2020. Deliberative methods ‘allow participants to consider relevant information from multiple points of view’ and enable them to ‘discuss the issues and options and to develop their thinking together’.[18]

Through this approach, the ICO presented information about their proposals to the Council members and answered questions. Council members then discussed the information they’d heard with one another in groups of five or six, in response to prompts given by an impartial facilitator from the Hopkins Van Mil team. These facilitators are a fundamental component of deliberative methodologies; in addition to prompting topics of discussion, they also moderate the conversation, ensuring everyone’s views are heard and that the process remains on topic and constructive.

This process took place across three online workshops, which followed this structure:

| Workshop 1

1 November 2022, 6–7.30pm |

Workshop 2

10 November 2022, 6–8pm |

Workshop 3

17 November 2022, 6–8 pm |

| · Welcome the Council members

· Introduce the purpose of these workshops · A presentation from ICO staff to describe their regulatory and advisory powers in relation to biometrics · A presentation from Ada Lovelace Institute staff to recap the topic of biometrics and what the Council discussed in 2020 |

· Focus on research questions 1 and 2

· Two presentations from ICO staff to describe their draft guidance for biometrics and their foresight work · Facilitated small group discussions among the Council members |

· Focus on research questions 3 and 4

· A presentation from Ada Lovelace Institute staff to recap the purpose of these workshops and topics discussed so far · Facilitated small group discussions among the Council members · Bring together final considerations across the groups’ discussions |

The workshops were carried out online, via Zoom. Traditionally, public deliberation and dialogue has been conducted in person, however the COVID-19 pandemic facilitated a shift towards the use of online and videoconferencing-based approaches. Both in-person and virtual workshops have strengths and limitations. For example, where in-person workshops are generally considered to enable richer discussion, online workshops can be more accessible and convenient for participants, as well as reducing other barriers to participation.

The Council members had already experienced working together in online workshops during the COVID-19 lockdown. They had developed a good rapport and felt at ease with the facilitators in an online environment.

Online engagement space

In addition to the workshops, the Council members had access to an online platform called Recollective, which was tailored for the Council deliberations.

This platform was used to share information and materials with the Council, such as the presentation slides from the workshops, a handbook of information about biometrics, case studies of specific biometric technologies and further materials about the ICO’s proposed guidance.

On this platform, Council members were given ‘homework tasks’ between workshops, such as reviewing and commenting on materials, or answering specific questions designed to gather more detailed information about their views.

Reflections from Hopkins Van Mil on reconvening the Citizens’ Biometrics Council

Why reconvene?

The Citizens’ Biometrics Council was originally intended to run for three months in 2020. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic the Council’s deliberations included both in-person weekends and online evening sessions, for nine months. This led to a very committed and engaged group of people, who had reflected deeply on biometric technologies and their use and misuse.

When the ICO and Ada jointly came to Hopkins Van Mil with the idea of reconvening members of the Council to consider their proposed guidance, their rationale for doing so made sense to us immediately. It was clear that the ICO’s team took seriously the recommendations the Council had made in 2020 and was now seeking meaningful input from its members at a key stage in the development of future policy.

Frequently in our deliberative work we wonder, ‘what would the group say about this development, or this policy?’ and we have no way of finding out. It is often also a regret that people who have committed hours of their time to deep reflection on an issue are not able to continue to share their views with policy- and decision-makers. The ICO decision to involve the Council in these deliberations felt inspired.

The commitment of the Citizens’ Biometrics Council

Within 48 hours of contacting the original Council, 32 of the members had responded to say they would like to join the ICO-focused deliberations. It was clear from their responses that they were keen to find out how their recommendations had been taken on board by the ICO. This eagerness to rejoin the Council was a powerful reflection of the interest in this complex and fascinating subject and a desire to see the Council’s recommendations taken forward.

The value of reconvening

Reconvening the Council has been a highly valuable experience. We believe there are three main reasons for this, which could inform other deliberative processes:

- Diving straight in: a group of people already familiar with the issues and who have explored their own hopes, aspirations, concerns and challenges are immediately able to respond to key policy questions on the topic. We embedded ‘getting re-acquainted with the topic’ discussions in the first of the three deliberative workshops, but these were not needed. The Council dived straight in to complex and nuanced conversations.

- Trusted relationships: the Council, as a group of people who already understand the deliberative process and who have already seen their carefully honed recommendations having an impact, could trust that the ICO and Ada would take their words seriously. They know that what they have said in these workshops will have an influence on the ICO’s biometric guidance.

- Deep insights: enabling people to continue to engage with a tricky societal challenge over time brings depth and richness to the research and engagement process. It provides an opportunity to revisit topics with the power of reflection time, building on robust evidence, to create insights which genuinely inform policy and practice.

As one member of the Council put it,

‘Thank you all for a wonderful and insightful conversation on biometric technologies. This round of workshops felt particularly great as we were also working alongside the ICO. As they are the independent body regulating the use of biometric technologies, we knew our points of view were very much appreciated.’

We hope others who engage with diverse publics on complex issues can draw from this experience to create meaningful opportunities to understand people’s views on the issues that challenge and matter most to society.

Findings

Council members came to the deliberative workshops in November 2022 with nuanced views, a product of their previous deliberations in 2020/21 as the Citizens’ Biometrics Council. They left the workshops with similarly balanced perspectives on biometrics, with many describing themselves as being ‘on the fence’, having ‘mixed feelings’, or ‘seeing both sides’. This reflects how Council members continued to see the value of biometric technologies in some circumstances while also keeping in sight the many concerns that are yet to be addressed.

Most of the benefits Council members identified around biometrics related to personal and public security, for example keeping personal information safe and secure from ‘hacking’ or fraud, or supporting police forces to tackle crime. Other benefits related to ease and convenience, such as making it quicker and more accessible to log into a device or online account.

However, these perceived benefits were counterbalanced by a range of issues and concerns that formed the basis for Council members’ deliberations in response to the ICO’s proposals. We detail these concerns and the Council members’ feedback for the ICO below.

Overall responses to the ICO’s proposals

Overall, Council members felt that the ICO had taken strong steps towards addressing the concerns and recommendations they raised in 2020/21. Many found the existence of the ICO and the work it’s doing around biometrics ‘reassuring’ and they largely welcomed the ICO’s proposed guidance for organisations that process biometric data and use biometric technologies.

They were pleased that the ICO had taken the Council’s initial recommendations into account when developing the guidance. Many said they were reassured that the guidance addressed issues like accuracy, efficacy, data privacy, bias, discrimination, consent, proportionality and transparency through the lens of the data protection principles.

‘I really liked the information around fairness and recognising bias. I know that not a lot of people can always access biometric data or use biometric data in the way it’s intended to be used so I really liked that the ICO provided guidance on that.’

‘I’d say it’s encouraging because we’re being listened to and guidance [will be] set in place.’

‘Yes, I actually do feel more confident because for me, three of the main things were to do with fairness, consent and transparency, and all of those seem to be addressed by the proposals that the ICO outlined. So it is reassuring.’

‘I think the guidelines are a necessity. I mean, you’ve got to start somewhere.’

Some of the Council members shared how the ICO’s existing regulatory and enforcement powers did go some way towards addressing their initial recommendation that an independent regulatory body should exist to oversee the use of biometric technologies and their associated data processing.

However, there were frequent and lengthy discussions among the participants about where they felt the ICO’s powers were limited. For example, Council members often questioned whether the powers of the ICO would be effective and have sufficient ‘teeth’ to prevent misuse.

‘Whether they really have the teeth is questionable.’

‘They seem pretty toothless to me. Their ability really is just to say, “Oh, we’re going to give you a jolly good telling off.” And that’s going to make people change their ways. I mean, how effective is that really going to be?’

This concern around effective regulation was related largely to two things. Firstly, Council members questioned whether the ICO’s enforcement powers were sufficient to discourage all wrongdoing. For example, some questioned whether a multimillion-pound fine was anything more than a ‘cost of doing business’ to a multibillion-pound company. Others wondered whether more powerful sanctions, such as even greater fines or custodial sentences for the executives responsible, would be required to prevent misuse. Secondly, Council members were concerned about the ICO’s available resources and how practically effective it could be at inspecting biometric data uses, given their increasing proliferation.

‘I’m not saying that what the ICO is doing is wrong or anything, it isn’t. Just the more you look at it, I feel quite despondent that actually, it’s a hell of a task to try and control this, isn’t it?’

‘The thing is, they can issue a penalty, some kind of notice, some kind of fine. But the large companies will have better lawyers than public service companies have. It’s as simple as that. They’ll get around it. Whoever’s got the best lawyer usually wins.’

‘But what are the penalties? […] If it’s a couple of million here or there, someone like Elon Musk can just take it out of the bankroll, and say, “Here you go, keep the change”. So it has to be something really tough.’

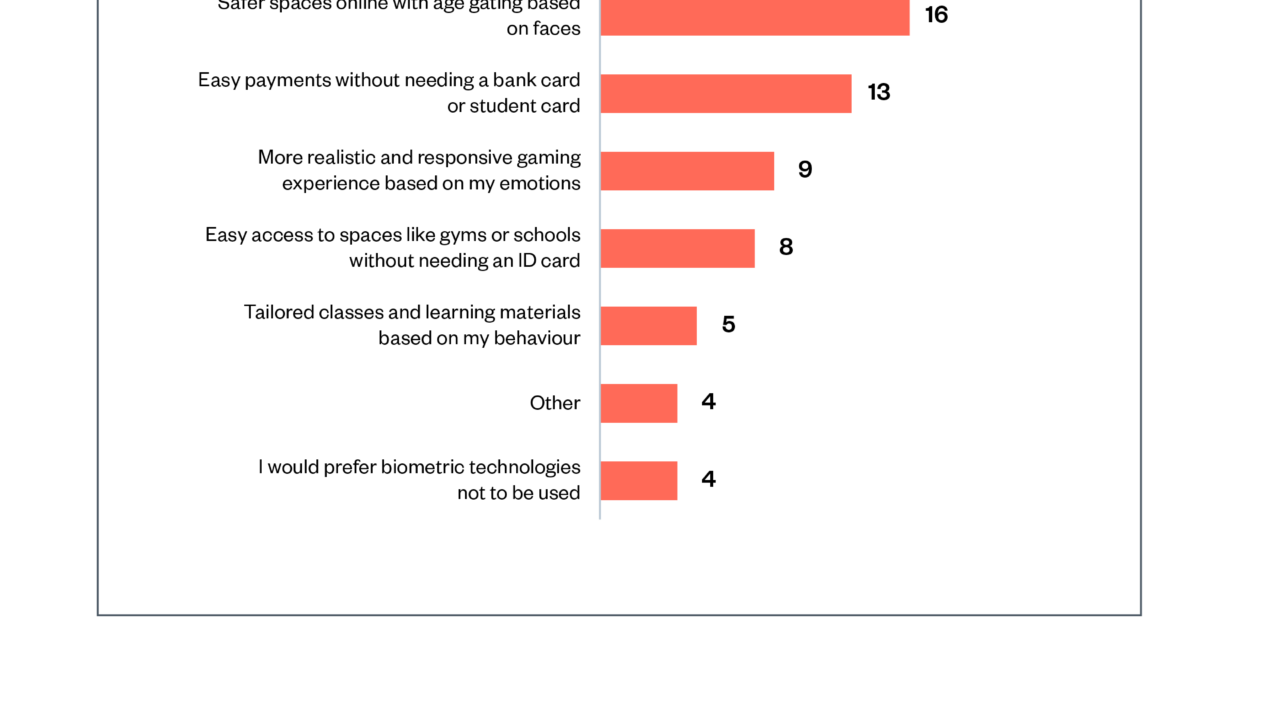

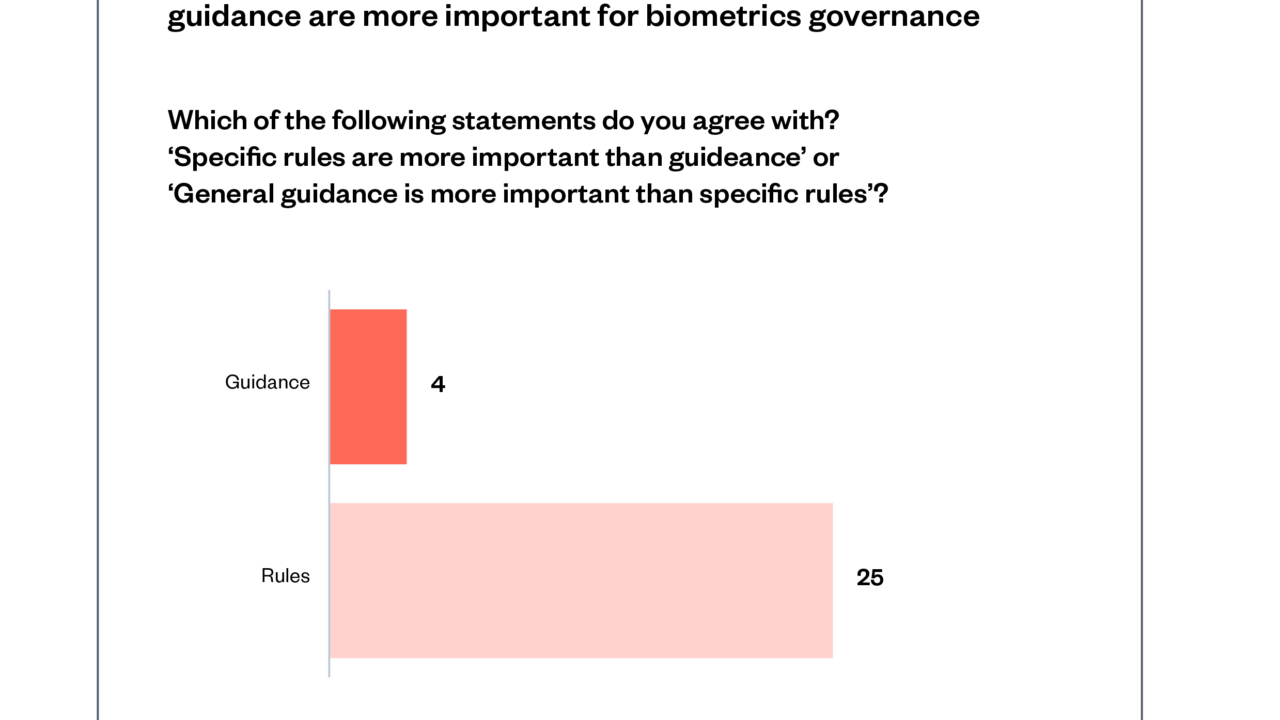

The strength of this concern is demonstrated through the Council members’ response when asked whether guidance or rules are more important when thinking about biometric governance. Here, ‘rules’ were considered by Council members as binding codes that must be followed (such as a law or an industry standard) where ‘guidance’ was advisory. 25 out of 29 Council members said rules are more important than guidance.

As part of their discussions, Council members commented that the ICO’s powers appeared to them to be largely retroactive and might only take effect after the law has been broken. For many, this caused concern, particularly as the harms related to biometric data misuse are often hard to undo. Some Council members shared ideas around more proactive ways to govern biometrics, such as developing a transparent and open register of where biometric technologies are in use in the UK, or developing ‘licensing’ or ‘approval’ mechanisms for organisations seeking to process biometric data.

‘I think it’s good to see that anti-discrimination and anti-bias is being looked at and thought about, because that was something we reflected on strongly.’

‘I’m a bit surprised that the guidance seems to be a bit retroactive. It’s essentially saying that people can deploy technology that’s biased and then work it out as they go. I don’t think that’s the right approach.’[19]

‘The ICO can’t possibly know every single company that is using biometric technologies. Do they have to sign up to tell people that they are using them? […] How do they find out about these companies because anyone, willy-nilly, could easily make a new app and collect lots of this data, but then the ICO might not know anything about them. And if they are going against the rules and aren’t following the guidance, then how do the ICO find these companies unless someone grasses them up?’

For one Council member, the ICO’s regulatory sandbox initiative – which supports organisations to develop their data technologies in line with the legislative framework – offered aspects of a more proactive approach:

‘I think [the sandbox idea has] made me feel more confident. Just the fact that if companies are going to be using biometric technologies, they can then sit down with the ICO and go through everything in detail, rather than struggling on the sidelines thinking, “We want to come in and use this but we’re not really sure what we should do.”’

Government and legislation

There were several occasions during the Council members’ deliberations where they discussed the wider legislative and governance context of biometrics. During these discussions, several Council members expressed concern that guidance, while useful in influencing better practices, won’t stop publicly unacceptable behaviour outright, especially if that behaviour is legal despite being undesirable. Here, questions relating to the legislative framework for biometrics resurfaced, echoing those discussed at length in the Council’s original deliberations in 2020.

‘It’s great having all these guidelines and stuff, but in terms of power, the legislation and the laws aren’t really effective I don’t think.’

‘What’s the difference between law and guidance? […] If they’re guiding me to do something, I’m not going to be prosecuted as long as I’m working within the law. It just seems quite messy to me, and I think it needs to be tightened up.’

Many Council members acknowledged that ultimately this is a question for Government, as the ICO does not have the authority to directly shape the legislative framework around biometrics (though some expressed a desire that it did). Nevertheless, many felt that unless legislative frameworks relating to biometrics are strengthened, their concerns will remain unaddressed.[20]

‘My concern is that the ICO doesn’t have the power to create or change the law. Who does? Except for Government.’

‘The ICO can warn, fine, etc. But they can’t change legislation, so they’re working on the basis of legislation that’s currently in place. Do they have any powers to make recommendations for new legislation?’

There was a positive response from Council members when they heard about the ICO’s policy work, including consulting with civil society groups, government departments and other regulators.

Public awareness, engagement and participation

Several Council members reflected on how there is relatively little awareness of biometric technologies and data use, or of the ICO’s actions, among the general public. This was emphasised by some Council members who pointed out that if they hadn’t been part of the Council, they wouldn’t know much, if anything, about biometrics.

‘With all these different types of biometrics, when do the general public get a say? I talked to my mum about this and she says “I’ve never heard of it.” She wouldn’t have known anything about this unless I’d been talking to her about it.’

Council members also reflected that publicly available information about the use of biometric technologies and data is scant, even when it is in use. Council members felt that companies and organisations who deploy biometrics should do more to be transparent about where they use biometrics, what data is collected, how it’s used and why.

‘Organisations that are collecting biometric data need to go on a register to say, “Hey, yes, we’re taking photographs of everybody that comes in,” or whatever information, “We’re storing it, and we’ve got that information.” So that you as an individual can then say, “Wait a minute, right. I need to find out about that. What information have they got? Is it accurate? What’s going on?”’

‘[An app I use] says ”next time, log in using biometrics.” Well, you’re not actually giving me any details with regard to what you’re going to do with my data, where it’s going to be stored or anything at all.’

Council members also commented how there is little public awareness of the ICO’s work in relation to biometrics, and that greater awareness would be useful in supporting public confidence and reassurance around biometrics.

The points around awareness of the ICO’s work generally related to two topics. Firstly, Council members felt that the ICO had a responsibility to provide information about responsible and lawful biometric use not only to businesses and organisations, but to the general public too. This would create more public confidence that there is an institution ensuring biometrics are used lawfully, and for helping people to understand their rights in relation to inappropriate or unlawful biometric data use.

‘There needs to be a lot of public discussion [about biometrics] and maybe the ICO can lead that.’

‘I don’t think many people know a great deal about what’s happening and how much [biometric] data is being collected. So, I do think it would be good to have some sort of campaign to make the public more aware.’

Secondly, some Council members suggested that more public awareness about where the ICO has taken enforcement action in relation to biometrics would be positive in boosting public confidence. One Council member described this as the ICO ‘exposing’ misuse of biometrics.

‘I’d like to see what they will do in the event of the consequences of biometric technology being abused.’

‘Although they talked about [how] they fined someone 16 million pounds, almost all the enforcement came down to advice and guidance. It was a little bit vague about how many actual prosecutions there have been. It sounded like there were a few very high-profile prosecutions but the rest of it was, to be honest, just talk. And talk, and guidance, and advice is very often the appropriate response, but I wasn’t convinced that there was really a whole lot of real enforcement and prosecution going on.’

Some Council members felt it was important that the ICO continues to engage with the public and advocate for their concerns in their policy-related work. Many Council members welcomed the opportunity to engage with the ICO through these workshops and felt that continued public engagement would be important if the ICO is to earn the public’s trust.

‘I think for society to be confident in the ICO making sure these biometric technologies are being used properly, we’ve got to understand exactly how they’re going to do it and what resources they actually have to do it.’

Consent

The issue of consent remained a significant concern for many Council members. Some observed that biometric technologies have the potential to become increasingly pervasive in everyday society, present in supermarkets, in schools, hospitals, on our personal devices and online. The nature of such ubiquitous use of biometrics led some Council members to recognise the practical challenges around actively giving consent, and others worried that there might not be adequate choices for data subjects about whether or not to consent to biometric data processing.

Some were worried that this increasing use of biometrics across society would result in either assuming people’s consent passively or rendering any active consent given meaningless, as it wouldn’t be fully informed or made freely.

‘Consent is also difficult as well, I have no idea how many times I’ve been photographed today walking down the street. I haven’t given consent of any of that because I don’t actually know what it’s used for. So consent is also quite a complicated beast. This is not criticism. This is a recognition of the fact that it is a complicated beast and it’s going to be damn hard to manage.’

‘If everyone is forced to give consent, it’s not consent.’

‘I don’t think we have any consent at all. Any website, any shop, any app on your phone, there is no choice, you have to agree for everything they do or else you can’t move. Even simple things like phoning the bank. If you don’t do the voice recognition, you’re in a queue. If you conform to the voice recognition, you’re answered faster. Well that’s not reasonable and fair but that’s the reality of today.’

‘What concerned me slightly was, […] if we go back to the [example given by another Council member] who went on a cruise, there was no other alternative but to have the facial recognition. They didn’t offer any alternative at all. They said about having an alternative there, there wasn’t one from what they said. That worries me a little bit.’

Several Council members responded positively to the practical examples of meaningful and fair consent mechanisms that will be included in the ICO’s planned guidance. However, the prominence of consent in the Council members’ discussions throughout the workshops suggests that it remains an issue for them.

‘I liked the examples about […] if you have to go up a flight of several stairs to get access to a building without giving any biometrical data away, that is completely unfair.’

‘I actually found the consent part quite clear, and I thought that was right, what was being described.’

Accessibility and inclusion

Another prominent topic for Council members was how the use of biometric technologies and data has the potential to exclude people. This might be because a particular biometric technology is not designed inclusively, for example reliance on fingerprint recognition technology might present a physical barrier to people with disabilities or health conditions related to their hands or fingers.

‘I am worried about the way biometrics are going. […] What is it doing for disabled people? We’ve just seen videos of using hands and I’ve got no chance because my fingers aren’t straight. So what’s going to happen with people like us, are we going to be left behind?’

‘How are they going to deal with disabled people? Because they’re on about fairness, but how are they going to help people that have got medical problems such as mine?’

Digital exclusion could also be exacerbated where the use of biometric technology presents a barrier to people who are not confident in the use of digital technologies, or who do not have access to a smartphone or other devices that might be required.

‘I just taught my mum how to use the ATM with her debit card. And now it seems we’ve already moved 2 or 3 steps forward in a completely different direction, and I think not everyone’s going to be able to keep up.’

Council members’ concerns around the potential lack of accessibility and inclusion were amplified by the perceived lack of choice or alternatives where biometrics are used:

‘I wouldn’t have been able to access something like that, so anybody that has some form of mobility impairment or something like that would find those things kind of difficult, and there should also be some kind of alternative option for those people too.’

These concerns ultimately reflect that, while several Council members recognise the potential for biometrics to make the world more accessible, there is concern that an over-reliance on poorly designed biometric technologies will create more barriers for people who are disabled and/or digitally excluded.

Technological change

Throughout discussions, Council members expressed concern about the way in which biometric technologies and data uses are constantly developing, and that the future may hold unknown and undesirable biometric technologies.

The ICO’s future horizon-scanning exercises provided some comfort for Council members who raised this concern, though some questioned what the ICO could (or should) do if it identifies a forthcoming use that might raise legal, ethical or societal questions that are outside the scope of existing legal frameworks and ICO powers.

‘In reality, do we really know what’s happening in the next 12, 18 months, 2 years? Especially up to 5 years down the line. You know, things are moving at such a pace that what we think is possible now will be more than possible.’

‘I think future-proofing the guidance and the laws [is important] because it’s starting to build momentum. I remember when we first talked about what was possible back during COVID in 2020 or whatever, and things have moved on so fast now, it’s just a case of these laws and guidance keeping up with technology because [biometrics are] becoming more intrusive.’

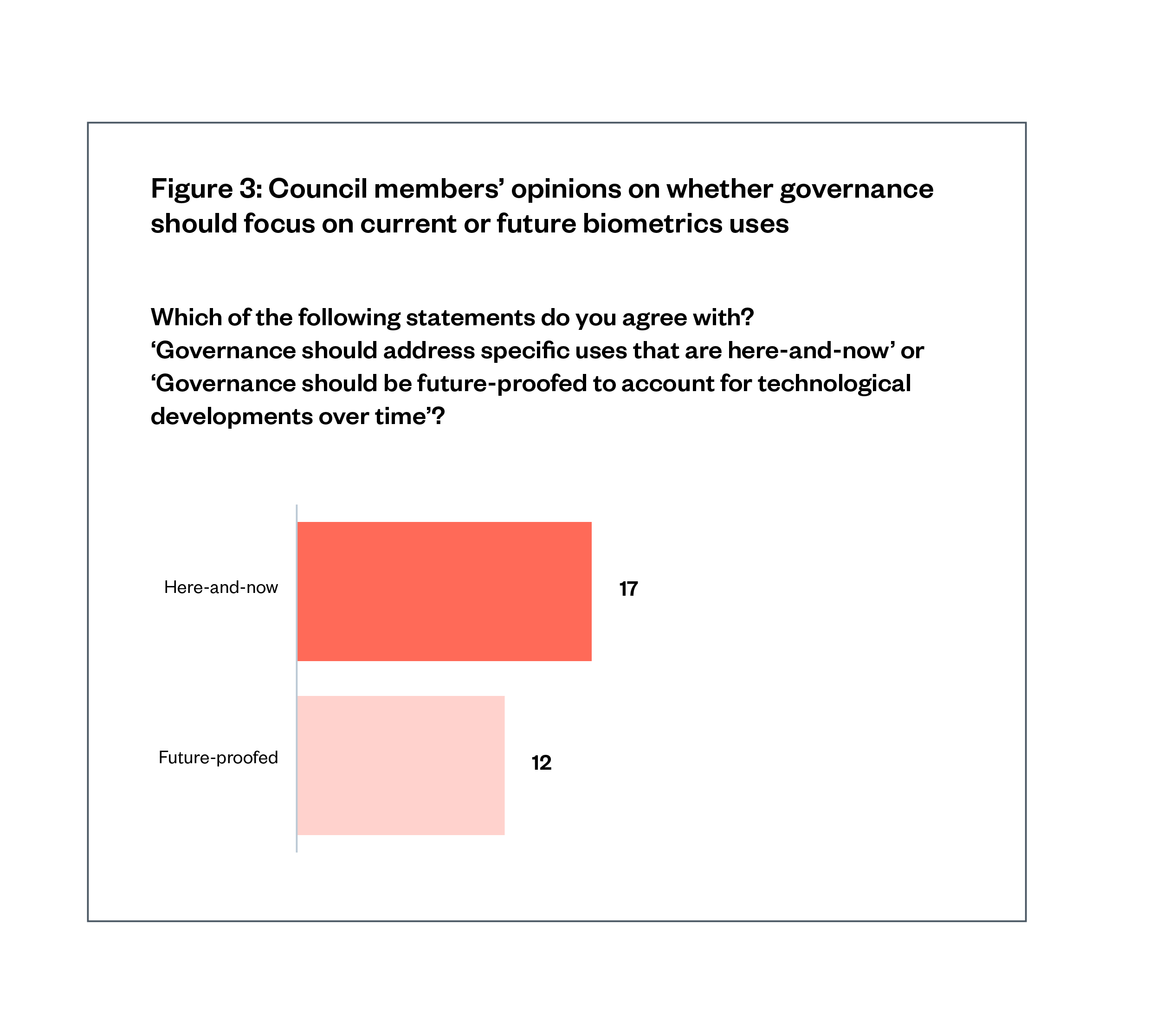

When asked whether focusing on current or future issues was more important, Council members leaned slightly towards future issues. This suggests both are concerns for them, but there is still a great deal of uncertainty around the future of biometrics, at least among this informed group.

International contexts

Some Council members raised concerns around the international contexts, recognising that many biometric technologies are developed or deployed by companies overseas. The ICO’s jurisdiction covers any use of data about UK citizens, but Council members still had concerns about how realistic it is that data collected by companies based overseas can be effectively regulated by a UK regulator. Some felt that the ICO engaging with regulators in other countries and regions would be a positive step.

‘I think it would be good for the ICO to talk with similar organisations in European countries, or maybe North America or Australia. […] It would be good if [they] could think jointly about how they can deal with these issues and deal with companies that are obviously global companies.’

Types of biometric data

Council members raised the point that not all biometrics are the same. Fingerprints, DNA, faces, voices etc., all have different properties and while they are often used for similar purposes, they each raise unique considerations. The accessibility and bias issues related to voice recognition, for example, are not equivalent to the issues around faces or fingerprints. Similarly the information that can be inferred from voices is different from the information that can be inferred from DNA.

‘The actual definition of what you mean by biometrics in terms of what are you talking about, are you talking about my thumbprint, are you talking about my DNA? We’re not, we’re just talking about them as general terms. And that, for me, is a big worry and therefore, I don’t have confidence at the moment.’

In practice, some of these data types do fall under additional protections. For example, DNA is genetic data, which falls under special category data regardless of how it is used.

The Council members’ concerns around the different types of biometric data – and the various ways they may be used – suggest some action may be needed to explain these details in both the guidance and to the wider public.

Children and schools

Several Council members raised concerns about the idea of biometric technologies being used in relation to children and in schools. These concerns related to whether children would be able to give informed consent, and to the idea of ‘normalising’ biometric technologies to children in potentially harmful ways.

‘Children can’t give informed consent because they’re not aware.’

‘But when it gets down to stuff like monitoring children, I just don’t think there’s any need for that technology. I think it’s just discriminatory and, honestly, it’s not even an advancement, if anything it’s stepping back.’

Some Council members also disliked the idea of biometric technologies being used in educational settings, such as monitoring student performance or attendance. They feared this would be discriminatory, would impact children’s wellbeing or would diminish the quality of education children receive.

‘You certainly don’t need biometrics to test children in school. Children in school have got enough problems, they don’t need biometrics to stress them out further or to collect data that the police can use when they’re 16 or 17.’

‘I wasn’t happy with the video of the children being monitored in school, if they’re paying attention or not, and then reporting back to the parents. I think that’s just control. That should not be allowed to happen to children.’

‘Children are children, and I’m worried that biometrics is going to go so far that we’re going to have robots instead of children.’

Final comments from the Council members

At the end of the workshops, Council members were asked to share final thoughts, comments or advice with the ICO. Below we report their responses in full, in their own words:

| ‘Strive to be unbiased and transparent.’ | ‘Do more discussions like this in various public forums, like newspapers, TV debates, university courses, etc. The better informed the public are, the better we can all be guided.’ |

| ‘Make sure security is much more secure.’ | ‘Be specific, be clear, say how not just what. Increase penalties, don’t rush it out; properly is better than quickly.’ |

| ‘Public confidence and corporate engagement need to go hand in hand. The public need to understand what you’re doing.’ | ‘Stick to your guns over the valid points and concerns about future and current guidance and law.’ |

| ‘Please have stronger guidance to protect the public and more specific guidelines.’ | ‘Keep going and stick to the task.’ |

| ‘Always consider the ethics.’ | ‘Develop core rules that all organisations must abide by as a minimum. Make these vague enough that they can be applied to future applications but specific enough to plug loopholes. You can then add tailored rules as technology evolves.’ |

| ‘Make sure biometrics is always 100% before using it.’ | ‘Be transparent.’ |

| ‘Listen to the people, don’t make things too complicated for companies to understand.’ | ‘ICO could implement a department to develop trainers to be able to do workshops at schools.’ |

| ‘Consider how you can educate the public’s understanding of biometrics, and how the ICO is involved in supported and governing the industry.’ | ‘It’s important to show the world that you can be trusted. Make sure your policies are followed and build a history of being trustworthy by doing a good job.’ |

| ‘It is really important that as technology is moving so quickly the policy needs to be looked at on a regular basis.’ | ‘Details! The use of concepts like “biometrics”, “consent” and “ethical use of data” need to be broken down to a more granular nature. The use of facial images may not be as important as using DNA data. What about data that has already been collected?’ |

| ‘Be as clear and concise as you can be – where you can’t, then be honest!’ | ‘Do a documentary about biometrics.’ |

| ‘Be ever-changing and diligent.’ | ‘Give guidance on age limits for biometrics.’ |

Conclusion: considerations for the ICO

The Council members’ discussions covered a broad range of topics, from direct responses to the ICO’s proposals to in-depth reflections on issues such as consent and accessibility. Drawing on these findings, the Ada Lovelace Institute has identified several considerations for the ICO as they develop their guidance on biometrics and continue other work in this area.

Considerations for the ICO:

- Guidance as a first step: Broadly, Council members welcomed the ICO’s proposed guidance for organisations that collect and process biometric data, and saw it as a positive first step towards addressing their concerns. The Council members’ feedback should be used to refine this guidance, and to point towards future action by the ICO or other bodies, such as developing codes of conduct or legal changes, to ensure biometrics regulation addresses the views expressed during both the November 2022 workshops and those in 2020 and 2021.

- Biometric legislation and policy: While directly changing the legislative framework is outside the ICO’s remit and authority, the Council members’ comments express a desire that the ICO continues to convene and consult with government, industry, academia and civil society as the laws around biometrics and data protection are debated. In doing this, the ICO should advocate for the wants and interests of the public, as evidenced through public participation activities such as these workshops.

- Public engagement and awareness of the ICO: Council members’ comments demonstrate that more ICO-led public engagement and communications would be beneficial. This could include raising public awareness of where the ICO has taken enforcement action, as well as producing a version of the guidance that is more accessible to the general public, and details data subjects’ rights and organisations’ obligations. It could also include further public dialogue and participation on biometrics, as well as other issues related to the ICO’s work.

- Accessibility and inclusion: through the forthcoming guidance, the ICO could encourage biometrics developers and deployers to ensure their technologies are accessible to different people. This includes ensuring that there are alternative mechanisms in place when the use of biometrics poses a barrier or for those who do not consent.

- Ethical and social concerns: the ICO could further consider how it can address ethical and societal issues of biometric data use – such as consent, accessibility, categorisation and so on – through its guidance and other activities, while remaining within its remit. For transparency in particular, the ICO could ensure that their forthcoming guidance encourages and supports those developing and deploying biometrics to provide clear, plain-English explanations of purpose, data collection and storage, and optout processes for data subjects.

The findings from the Council members’ deliberations suggest that, for informed members of the public, issues of consent, transparency, effective legislation and oversight, accessibility and inclusion remain central. These findings may therefore have relevance for other regulators considering biometric technologies and data, as well as organisations that develop and use biometrics and governments considering how to approach the regulatory landscape of biometrics – in the UK and beyond.

Moreover, these findings are a reminder that members of the public do not see the issue of biometrics as clear cut or straightforward. Instead, they recognise the complex nuances of the technology, both in the benefits it could bring and in the multiple concerns it raises. This reaffirms how the rise of biometric technologies and data use must be met with careful, considered approaches to governance and oversight in line with public expectations and values.

A final, but important note, is that the ICO’s engagement with the public was welcomed positively by all Council members. They felt that the ICO were taking the public’s concerns seriously and are dedicated to advocating for and acting on the behalf of the public, even though anxiety remains about the future of biometrics:

‘I’m feeling positive about how our recommendations have been taken on board but still somewhat apprehensive about how biometric data will be used.’

Acknowledgements

This paper was lead authored by Aidan Peppin. The Ada Lovelace Institute is grateful to a number of colleagues for their time, expertise and supportive contributions to the Citizens’ Biometrics Council.

Hopkins Van Mil: Henrietta Hopkins

Hopkins Van Mil is an independent social research agency. We create safe, impartial and productive spaces to gain an understanding of people’s views on what matters to society. We work flexibly to build trust. HVM has extensive experience in preparing for, designing and facilitating effective deliberative processes. We hold a lens up to issues which are contentious, emotionally engaging and on which a broad range of viewpoints need to be heard.

Citizens’ Biometrics Council members

The Citizens’ Biometrics Council would not have taken place or been successful without the time, dedication and thoughtfulness of the Council members. We are incredibly grateful to all of them for taking part:

Allison B

Arron C

Colin M

Elaine R

Emma W

Hung Kai L

Jim H

Jonathan O

Krishna P

Liam S

Lionel J

Mark H

Natalia R

Modichaba M

Rachel E

Susan C

Tina D

And those who preferred not to be named.

Footnotes

[1] ‘Guidance on Biometric Data’ (ICO.org.uk) <https://ico.org.uk/for-organisations/uk-gdpr-guidance-and-resources/guidance-on-biometric-data/> accessed 18 August 2023

[2] Ada Lovelace Institute, The Citizen’s Biometrics Council (2021) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/citizens-biometrics-council/>

[3] Matthew Ryder, The Ryder Review (Ada Lovelace Institute 2022) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/ryder-review-biometrics/> accessed 3 January 2023

[4] Ada Lovelace Institute (n 2)

[5] Luke Stark and Jesse Hoey, ‘The Ethics of Emotion in Artificial Intelligence Systems’ (2021) Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, FAccT ’21 Association for Computing Machinery, pp. 782–793 <https://doi.org/10.1145/3442188.3445939>

[6] Lisa Feldman Barrett and others, ‘Emotional Expressions Reconsidered: Challenges to Inferring Emotion From Human Facial Movements’ (2019) Psychological Science in the Public Interest <https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100619832930>

[7] Os Keyes, ‘The Misgendering Machines: Trans/HCI Implications of Automatic Gender Recognition’ (2018) 2(CSCW) Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, pp. 1–22 <https://doi.org/10.1145/3274357>

[8] ‘Data Protection and Digital Information Bill – Parliamentary Bills – UK Parliament’ <https://bills.parliament.uk/bills/3322> accessed 19 December 2022

[9] Luca Bertuzzi, ‘AI Act: EU Parliament’s discussions heat up over facial recognition, scope’, Euractiv (6 October 2022) <https://www.euractiv.com/section/digital/news/ai-act-eu-parliaments-discussions-heat-up-over-facial-recognition-scope/> accessed 19 December 2022

[10] Hayley Tsukayama, ‘Trends in biometric information regulation in the USA’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 5 July 2022) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/blog/biometrics-regulation-usa/> accessed 19 December 2022

[11] Ada Lovelace Institute, Countermeasures: the need for new legislation to govern biometric technologies in the UK (2022) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/countermeasures-biometric-technologies/> accessed 3 January 2023

[12] Ada Lovelace Institute, Beyond face value: public attitudes to facial recognition technology (2019) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/beyond-face-value-public-attitudes-to-facial-recognition-technology/> accessed 3 January 2023

[13] Matthew Ryder, (n 3)

[14] Ada Lovelace Institute (n 2)

[15] Ibid.

[16] Jackie Street and others, ‘The use of citizens’ juries in health policy decision-making: A systematic review’ (2014) 109, Social Science & Medicine, pp. 1–9 <doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.03.005>

[17] Daniel Steel and others, ‘Rethinking Representation and Diversity in Deliberative Minipublics’ (2020) 16(1) Journal of Deliberative Democracy, pp. 46–57 <doi.org/10.16997/jdd.398>

‘Deliberative Public Engagement’ (involve.org.uk, 1 June 2018) <https://involve.org.uk/resources/knowledge-base/what/deliberative-public-engagement> accessed 3 January 2023

[19] It is important to note that this particular point made by a Council member partly reflects a misunderstanding. In practice, organisations cannot knowingly deploy biased (or otherwise unlawful) technology and ‘figure it out’ later. However, we have kept this quote in both our analysis and our report because it contributes to the strength of feeling around an important point relating to retroactive versus proactive regulation.

[20] Matthew Ryder (n 3)

Image credit: Jiraroj Praditcharoenkul

Related content

The Citizens’ Biometrics Council

Report with recommendations and findings of a public deliberation on biometrics technology, policy and governance

How to make a Citizens’ Biometrics Council

Answers to some of the most frequently asked questions about how we ran the Citizens’ Biometrics Council

Countermeasures

The need for new legislation to govern biometric technologies in the UK

Independent legal review of the governance of biometric data in England and Wales

An independent legal review of the governance of biometric data, commissioned by the Ada Lovelace Institute and led by Matthew Ryder KC.