Checkpoints for vaccine passports

Requirements that governments and developers will need to deliver in order for any vaccine passport system to deliver societal benefit

10 May 2021

Reading time: 220 minutes

The rapid development and roll-out of vaccines to protect people from COVID-19 has prompted debate about digital ‘vaccine passports’.

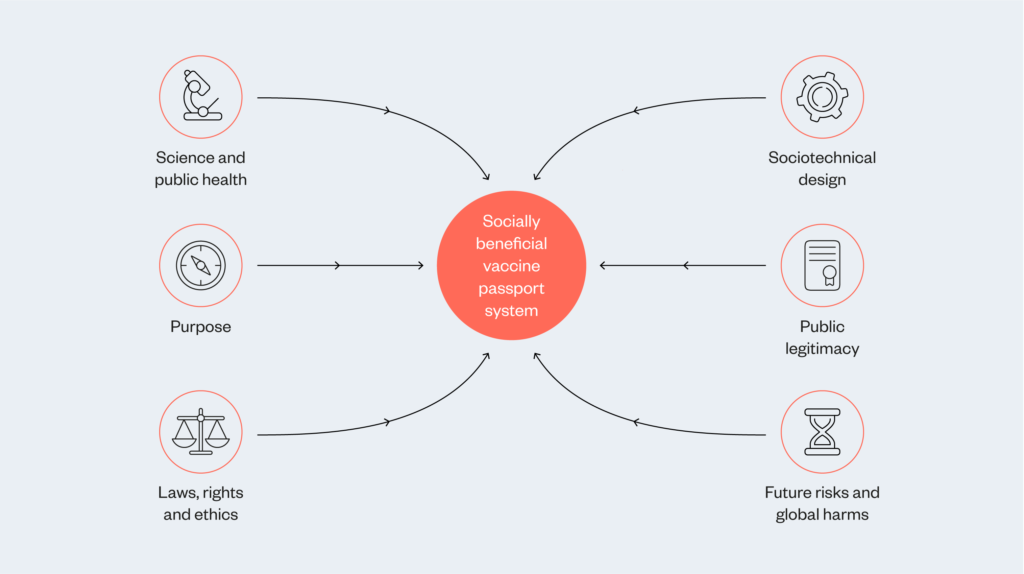

This report presents the key debates, evidence and common questions under six subject headings. These are further distilled in this summary into six requirements that governments and developers will need to deliver, to ensure any vaccine passport scheme builds from a secure scientific foundation, understands the full context of its specific sociotechnical system, and mitigates some of the biggest risks and harms through law and policy. In other words, a roadmap for a vaccine passport system that delivers societal benefit.

Checkpoints for vaccine passports

Requirements that governments and developers will need to deliver in order for any vaccine passport system to deliver societal benefit

Executive Summary

The rapid development and roll-out of vaccines to protect people from COVID-19 has prompted debate about digital ‘vaccine passports’. There is a confusion of different terms to describe these tools, which are also called COVID-19 status certificates. We identify them through the common properties of linking health status (vaccine status and/or test results) with verification of identity, for the purpose of determining permissions, rights or freedoms (such as access to travel, leisure or work). The vaccine passports under debate primarily take a digital form.

Digital vaccine passports are novel technologies, built on uncertain and evolving science. By creating infrastructure for segregation and risk scoring at an individual level, and enabling third-parties to access health information, they bring profound risks to individual rights and concepts of equity in society.

As the pandemic death toll rises globally, some countries are bringing down case numbers through rapid vaccination programmes, while others are facing substantial third or fourth waves of infection, and the mitigating effects of vaccination have brought COVID vaccine passports into consideration for companies, states and countries.

Arguments offered in support of vaccine passports include that they could allow countries to reopen more safely, let those at lower risk of infection and transmission help to restart local economies, and allow people to reengage in social contact with reduced risk and anxiety.

Could a digital vaccine passport provide a progressive return to a normal life, for those who meet the criteria now, while vaccines are distributed in the coming months and years? Or might the local and global inequalities and risks outweigh the benefits and undermine societal notions of solidarity?

The current vaccine passport debate is complex, encompassing a range of different proposed design choices, uses and contexts, as well as posing high-level and generalised trade-offs, which are impossible to quantify given the current evidence base, or false choices that obstruct understanding (e.g. ‘saving lives vs privacy’). Meanwhile, policymakers supporting these strategies, and companies developing and marketing these technological solutions, make a compelling and simplistic pitch that these tools can help societies open up safer and sooner.

This study disentangles those debates to identity the important issues, outstanding questions and tests that any government should consider in weighing whether to permit this type of tool to be used within society. It aims to support governments and developers to work through the necessary steps to examine the evidence available, understand the design choices and the societal impacts, and assess whether a roll-out of vaccine passports could navigate risks to play a socially beneficial role.

This report is the result of an international call for evidence, an expert deliberation, and months of monitoring the debate and development of COVID status certification and vaccine passport systems around the world. We have reviewed evidence and discussion on technical build, risks, concerns and opportunities put forward by governments, supranational bodies, collectives, companies, developers, experts and third-sector organisations. We are indebted to the many experts who brought their knowledge and evidence to this project (see full acknowledgements at the end of this report).

Responding to the policy environment, and the real-world decisions being made at pace, this study has, of necessity, prioritised speed over geographic completeness. In particular, we should caution that the evidence submitted is weighted towards the UK, Europe and North American contexts and will be more useful currently to policymakers in these areas, and in future to policymakers facing similar conditions – increased levels of vaccination and reducing case numbers – while navigating what are likely to be long-term questions of managing outbreaks and variants.

There are some factors for consideration that will be relevant to any conditions, for countries and states considering whether and how to use digital vaccine passports. These include the exploration of the current evidence on infection and transmission of the virus following vaccination, and some aspects of the technical design considerations and choices that any scheme will face.

A number of the issues – such as the standards governing technical development – will need to be considered at an international level, to ensure interoperability and mutual recognition between different countries. There are strong reasons why all countries should consider the potential global impacts of adoption of a vaccine passport scheme. Any national or regional use of vaccine passports that contributes to hoarding or ‘vaccine nationalism’ will produce extreme local manifestations of existing global inequalities – both in terms of health and economics – as the high rate of infection and deaths in India currently evidences. Prioritising national safety over global responsibility also risks prolonging the pandemic for everyone by leaving the door open to mutations that aren’t well controlled by existing vaccines.

Other requirements will be highly contextualised in each jurisdiction. The progress in accessing and administering vaccinations, local levels of uptake and reasons for vaccine hesitancy, legal regimes, and ethical and social considerations will weigh heavily on whether and how such schemes should go ahead. Even countries that seem to have superficially similar conditions may in fact differ on important and relevant aspects that will need local deliberation of what is justifiable and achievable practically, from the extent of existing digital infrastructure to public comfort with the use of technology, and attitudes towards increased visibility to the state or to private companies.

Incentives and overheads will look different as well. The structure of the economy – whether it is highly reliant on tourism for example, as well as the level of access to the internet and smartphones – will be important factors in calculating marginal costs and benefits of digital vaccine passports. And that local calculation will need to be dynamic: countries with minimal public health restrictions in place and low rates of COVID-19 face very different calculations in terms of benefits and costs to those in highly restrictive lockdowns with a high rate of COVID-19 in the community.

This report presents the key debates, evidence and common questions under six subject headings. These are further distilled in this summary into six requirements that governments and developers will need to deliver, to ensure any vaccine passport scheme builds from a secure scientific foundation, understands the full context of its specific sociotechnical system, and mitigates some of the biggest risks and harms through law and policy. In other words, a roadmap for a vaccine passport system that delivers societal benefit. These are:

- Scientific confidence in the impact on public health

- Clear, specific and delimited purpose

- Ethical consideration and clear legal guidance about permitted and restricted uses, and mechanisms to support rights and redress, and to tackle illegal use

- Sociotechnical system design, including operational infrastructure

- Public legitimacy

- Protection against future risks and mitigation strategies for global

harms.

These requirements (with detailed recommendations below) set a series of high thresholds for vaccine passports being developed, deployed and implemented in a societally beneficial way. Building digital infrastructure in which different actors across society control rights or freedoms on the basis of individual health status, and all the myriad of potential benefits and harms that could arise from doing so, should face a high bar.

At this stage in the pandemic, there hasn’t been an opportunity for real-world models to work comprehensively through these challenging but necessary steps, and much of the debate has focused on a smaller subset of these requirements – in particular technical design and public acceptability. Despite the high thresholds, and given what is at stake and how much is still uncertain about the pathway of the pandemic, it is possible that the case can be made for vaccine passports to become a legitimate tool to manage COVID-19 at a domestic, national scale, as well as supporting safer international travel.

As evidence, explanation and clarification of a complex policy area, we hope this report helps all actors navigate the necessary decision-making prior to adoption and use of vaccine passports. By setting out the features to be delivered across the whole system, the benefits and risks to be weighed, and the harms to be mitigated, we hope to support governments to calculate whether they can be justified, or whether investment in vaccine passports might prove to be a technological distraction from the central goal to reopen societies safely and equitably: global vaccination.

Recommendations summary for governments and developers

1. Scientific confidence in the impact on public health

The timeframe of the pandemic means that – despite significant leaps forward in understanding that have led to more effective disease control and vaccine development –scientific knowledge is still developing about the effectiveness of protection offered through tests, vaccines or antibodies that most vaccine passport models rely on.

Most of the vaccines now available offer a high level of protection against serious illness from the currently dominant strains of the virus. It is still too early to know the level of protection offered by individual vaccines in terms of duration, generalisability, efficacy regarding mutations and protection against transmission.

This means that any vaccine passport system would need to be dynamic, taking into account the differing efficacy of each vaccine, known differences in efficacy against circulating variants, and the change in efficacy over time. A vaccine passport should not be seen as a ‘safe’ pass or a proxy for immunity, rather as a lowering of risk that might be comparable to, or work in combination with, other public health measures.

Calculating an individual’s risk based on providing test results within a vaccine passport scheme avoids some of the problems associated with relying solely on vaccination, including access, take-up and coverage. A good negative test indicates that an individual is not currently infectious and therefore not a risk to others. However, this type of hybrid scheme requires widespread access to highly accurate and fast turnaround tests, as well as scientific consensus as to the window in which someone can be deemed low risk (most use 24–72 hours).

Evidence of a negative test offers no ‘future’ protection after that window, making it less desirable for a move to another city or entry to another country. Given that most point-of-care tests (tests that give a result at home) have a lower level of accuracy than tests administered in clinical settings, the practical overheads of reliance on testing may make this highly challenging for any routine or widespread use. If consistently accurate point-of-care tests become available, that might make testing a more viable route for a passport system, but would also reduce the need for a digital record – as people could simply show the test at the point of access.

Almost all models of vaccine passport attempt to manage risk at an individual level rather than using collective and contextual measures: they class an individual as lower risk based on their vaccine or test status, rather than a more contextual risk of local infection numbers and R rate in a given area. Prioritising this narrow calculation above a more contextual one may undermine collective assessments of risk and safety, and reduce the likelihood of observing social distancing or mask wearing.

A further important dimension is how the use of a vaccine passport affects vaccine take-up by hesitant groups – it provides a clear incentive to disengaged or busy people, but could heighten anxiety from those who distrust the vaccine or the state, if it is seen as mandatory vaccination or surveillance by the back door.

Before progressing further with plans for vaccine passports:

Governments and public health experts should:

- Set scientific pre-conditions, including the level of reduced transmission from vaccination that would be acceptable to permit their use; and acceptable testing regimes (accuracy levels and timeline).

- Model and test behavioural impacts of different passport schemes (for

example, in combination or in place of social distancing). This should examine

any ‘side effects’ of certification (such as a false sense of security, or impacts

on vaccine hesitancy), as well as responses to changing conditions (for

example, vaccines’ efficacy against new mutations). This should be modelled

in general and in specific situations (such as the predicted health impact if

used in place of quarantine at borders, or social distancing in restaurants), to

inform their likely real-world impact on risk and transmission. - Compare vaccine passport schemes to other public health measures in

terms of necessity, benefits, risks and costs, or alternatives – for example,

offering different guidance to vaccinated and non-vaccinated populations

without requiring certification; investing in public health measures; or greater

incentives to test and self-isolate. - Develop and test public communications about what certification should be

understood to mean in terms of uncertainty and risk. - Outline the permitted pathways for calculating what constitutes ‘lower risk’ individuals, to build into any ‘passport’ scheme, including: vaccine type; vaccination schedule (gaps between doses); test types (at home or professionally administered); natural immunity/antibody protection; and duration of reduced risk following vaccination, testing and infection.

- Outline public health infrastructure requirements for successful use of a passport scheme, which might include access to vaccine, vaccination rate, access to tests, testing accuracy, or testing turnaround.

Developers must:

- Recognise, understand and use the science underpinning these systems.

- Use evidence-based terminology to avoid incorrect or misleading understanding of their products. For example, many developers conflated the concept of ‘immunity’ with ‘vaccinated’ in materials shared with partners and governments, creating a false sense that these systems can prove if someone is immune.

- Follow government guidelines for permitted pathways to calculation of ‘lower risk’.

- Not release for public use any digital vaccine passport tools for use until there is scientific. agreement about how they represent ‘lower risk’ (as above).

2. Clear, specific and delimited purpose

It will be much easier to weigh the benefits, risks and potential mitigations when considering specific use cases (visiting care homes, starting university, or international travel without quarantine, for example) rather than generalised uses.

Based on the health modelling, there may be greater justification for some use cases of digital vaccine passports than others, such as settings where individuals work face to face with vulnerable groups. Countries are already coming under pressure to create certificates for international travel to selected destinations and this is likely to expand. There may also

be some uses that should be prohibited as discriminatory (examples to consider include accessing essential services, public transport or voting) and exemptions that should be introduced for those unable to have a vaccine or regular testing.

Developing clear purposes and uses should be carried out with consideration to public deliberation, and law and ethics (see below), and mindful of risks that could be caused in different settings, which might include liability for businesses or insurance costs for individuals, barriers to employment, as well as stigma and discrimination.

Before progressing further with plans for vaccine passports:

Governments should:

- Specify the purpose of a vaccine passport and articulate the specific problems it seeks to solve.

- Weigh alternative options and existing infrastructure, policy or practice to consider whether any new system and its overheads are proportionate for specific use cases.

- Clearly define where use of certification will be permitted, and set out the scientific evidence on the impact of these systems.

- Clearly define where the use of certification will not be acceptable, and whether any population groups should be exempted (for example children, pregnant women or those with health conditions).

- Consult with representatives of workers and employers, and issue clear guidance on the use of vaccine passports in the workplace.

- Develop success measures and a model for evaluation.

Developers must:

- Articulate clear intended use cases and purposes for these systems, and anticipate unsupported uses. Some developers consulted for this study said they designed their systems as ‘use agnostic’, meaning they failed to articulate who the specific end users and affected parties would be. Not having clear use cases makes it challenging for developers to utilise best-practice privacy-by-design and ethics-by-design approaches when designing new technologies.

- Utilise design tools and processes that seek to identify the consequences and potential effects of these tools in different contexts. These may include scenario planning of different situations in which users might use these tools for unintended purposes; utilising design practices like consequence scanning to identify and mitigate potential harms; and employing ‘red teams’ to identify vulnerabilities by deliberately attacking the tools’ digital and physical security features. For the sake of their own product’s effectiveness, it is essential that developers work back from the worst-case scenariouses of their tools to make necessary changes to technical design features, partnership and business models, and use this process to inform impact evaluation and monitoring.

3. Ethical consideration and clear legal guidance about permitted and restricted uses, and mechanisms to support rights and redress and tackle illegal use

Interpretation and application of ethics and law will be particularly local to regions’ jurisdictions, and – as described above – this report does not attempt to do justice to a fully international picture. There are of course some global agreements, and in particular the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and its two covenants, that are universally applicable.

Based on the debates around ethical norms and social values we have been following in the UK, USA and Europe in particular, there are a number of areas of focus in terms of ethics and law.

Personal liberty has been a significant concern in the debate – that vaccine passports might represent the least restrictive option for individual liberties while minimising harm to others. There are important legal tests, in particular respecting a range of human rights, particularly

the right to a private life, which must be considered where people are required to disclose personal information.

Wider concerns raised are around impacts on fairness, equality and non-discrimination, social stratification and stigma at both a domestic and an international level. Specific concerns about harms to individuals or groups, through facilitating additional surveillance by governments or

private companies, blocking employment or access to essential services, will need to be addressed.

Legal and ethical issues should be weighed in advance of any roll-out, and adequate guidance, oversight and regulation will be required.

Before progressing any further with vaccine passports:

Governments should:

- Publish, and require the publication of, impact assessments – on issues including data protection, equality and human rights.

- Offer clarity on the current legality of any use, in particular relating to laws regarding employment, equalities, data protection, policing, migration and asylum, and health regulations.

- Create clear and specific laws, and develop guidelines for all potential user groups about the legality of use, mechanisms for enforcement and methods of legal redress for any vaccine passport scheme.

- Support cooperation between relevant regulators that need to work cooperatively and pre-emptively.

- Make any changes via primary legislation, to ensure due process, proper scrutiny and public confidence.

- Develop suitable policy architecture around any vaccine passport scheme, to mitigate harms identified in impact assessments. That might require employment protection and financial support for those facing barriers to work on the basis of health status; mass rapid testing centres that can be flexed by need (for example, before major sports events) and guaranteed turnaround of results that is fast enough to be used in a passport scheme.

Developers must:

- Undertake human rights, equalities and data protection impact assessments of their systems, both prior to use and post-deployment, to measure their impact in different scenarios. These assessments can help clarify potential risks and harms of systems, and offer clear routes to mitigation. They should be made public and subject to scrutiny by an independent assessor.

- Consider the existing norms of social behaviour that these tools may change. Do these tools grant additional power to particular members of society at the cost of others? Do they open new potential for misuse? The misuse of data collected for contact tracing should act as a warning – contact tracing data from pubs being harvested and sold on to third-parties is an example of unforeseen behaviours that these tools may enable. Mitigating these risks should be built into the sociotechnical design (see below).

4. Sociotechnical system design, including operational infrastructure to make a digital tool feasible

Designing a vaccine passport system requires much more than the technical design of an app, and includes consideration of wider societal systems alongside a detailed examination of how any scheme would operate in practice.

When it comes to technical design, there are a number of models being developed that have different attributes and security measures, and bring different risks into focus. There are commonalities, for example QR codes are widely used with varying degrees of security, but the models are too disparate and varied to summarise in detail here. With some models bringing together identity information and biometrics information with health records, any scheme must incorporate the highest-level security.

Some risks can be minimised to some extent, by following best-practice design principles, including data minimisation, openness, privacy by design, ethics by design and giving the user control over their data. Governments also need to be careful not to allow rapid deployment

of COVID vaccine passport systems to lock in future decisions including around the development of wider digital identity systems (see requirement on future risks).

When it comes to the ‘socio’ part of sociotechnical design, governments need to decide what role they ought to play, even if they choose not to design and implement a system themselves (many developers described their role as ‘creating the highway’ and look to governments to decide the ‘rules of the road’).

Governments (alone, or acting through regional or international governmental institutions) are the only actor that can consider the opportunities and risks (identified above) in the round, and will need to offer legal clarity as well as monitor impact and mitigate harms, so should not step back from this question. They will need to ensure that the operational and digital infrastructure is in place across the whole system, from jab or test through to job or border.

Governments will also need to consider costs – including opportunity costs, maintenance costs and burdens on business – and impacts on other aspects of public health, including vaccination programmes, other public health measures, and public trust in health services and

vaccination.

Before progressing any further with vaccine passports:

Governments should:

- Outline their vision for any role vaccine passports should play in their COVID-19 strategy, whether they are developing their own systems or permitting others to develop and use passports.

- Outline a set of best-practice design principles any technical designs should

embody – including data minimisation, openness, ethics by design and privacy

by design – and conduct small-scale pilots before further deployment. - Protect against digital discrimination, by creating a non-digital (paper)

alternative. - Be clear about how vaccine passports link or expand existing data systems

(in particular health records and identity). - Clarify broader societal issues relating to the system, including the duration

of any planned system, practical expectations of other actors in the system

and technological requirements, aims, costs and the possible impacts on other

parts of the public health system or economy, informed by public deliberation

(see below). - Incorporate policy measures to mitigate ethical and social risks or harms

identified (see above).

Developers must:

- Consider how these applications will fit within wider societal systems, and

what externalities their introduction may cause. While governments should

articulate the rules of the road, developers must acknowledge values and

incentives that they bake into their design and security features, and how these

can amplify or mitigate potential harmful uses of their technology. It is essential

that developers work with local communities, regulators, businesses and

civil society organisations to understand risks introduced by their products,

and tests out how these systems are being used in practice, to understand

their externalities. Failing to do so will not only risk causing further harm to

already marginalised members of society, but lead to reputational damage and litigation or legal liability for developers. - Proactively clarify with regulators the need for clear legal guidance

on where these systems are appropriate prior to any roll-out or use of

specific applications. In the event a lack of clear guidance from governments

continues, this may result in firms, developers and their users facing legal

liability for misuse or abuse. - Ensure they develop their technology with privacy-by-design and ethicsby-design approaches. This should include data-minimisation strategies to

reducing the amount of data stored and transferred; consequence scanning

in the design phase; public engagement, in particular with marginalised

communities during design and implementation; and scanning for security

threats across the whole system (from health actors to border control). - Ensure their systems meet international interoperability standards being developed by the WHO.

- Work with governments and members of local communities to develop training materials for these systems.

5. Public legitimacy

Public confidence will be crucial to the success of a COVID vaccine passport system, and will be highly locally contextual. There are sensitivities involved in building technical systems that require personal health data to be linked with identity or biometric data for many countries. These combine with challenges in the wider sociotechnical system, including financial and other burdens on society, businesses and individuals, to produce concerns about potential harms. A system that is seen as trusted and legitimate could bolster hopes that it might encourage vaccination and updake of booster shots, or inspire more confidence in spaces that require vaccination or testing to enter.

Polling suggests public support for vaccine passports varies based on the particular details of proposed systems (including how they will establish status and in which settings), and concerns about discrimination and inequality. Polling to date only scratches the surface

of these new applications of technology, and deeper methods of public engagement will be needed to properly understand opinion, perceived benefits and risks, and the trade-offs the public is willing to make.

Before progressing any further with vaccine passports:

Governments should:

- Undertake rapid and ongoing public deliberation as a complement to, and not a replacement for, existing guidance, legislation and proper consideration of subjects mentioned above and throughout this report.

- Undertake public deliberation with groups who may have particular interests or concerns from such a system, for example those who are unable to have the vaccine, those unable to open businesses due to risk, those who face oversurveillance from policy or authorities, groups who have experienced discrimination or stigma, or those with particularly sensitivities about the use of biometric identification systems, for example. This would be in addition to assessing general public opinion.

- Engage key actors in the successful delivery of these systems (business

owners, border control, public health experts, for example).

Developers must:

- Undertake meaningful consultation with potentially affected stakeholders,

local communities and businesses to understand whether roll-outs of these systems are desired, and identify any risks or concerns. The negative reaction from parts of the hospitality industry in the UK should be a warning to developers who explicitly cite this use case as a primary reason for developing their system.1

6. Protection against future risks and mitigation strategies for global harms

If governments believe they have resolved all the preceding tensions and determined that a new system should be developed, they will also need to consider the longer-term effects of such a system and how it might shape future decisions or be used by future governments.

Risks to mitigate include the concern that emergency measures become a permanent feature of society. The introduction of vaccine passports has the potential to pave the way to normalising individualised health risk scoring, and could be open to scope creep post-pandemic, including more intrusive data collection or a wider sharing of health information.

Governments should consider the risk of infrastructure passing to future governments with different political agendas, and how tools introduced for pandemic containment could be repurposed against marginalised groups or for repressive purposes. More prosaically there

are maintenance and continuous development costs to consider, as well as path dependency for future decisions generated by emergency practices becoming normalised.

Equally pressing is how one national scheme affects the global response to COVID-19. Despite international coordination, there are significant inequalities of access to vaccines resulting in extreme differences in local manifestations of the virus – both in terms of health and economics. A legitimate concern is that wealthier countries rolling out vaccine passports could further contribute to exacerbating global inequalities, by incentivising vaccine hoarding. For example, vaccine passport schemes could encourage well-vaccinated and contextually low-risk countries to prioritise retaining booster shots to allow their citizens to take international holidays, rather than incentivise global vaccination – which is the only definitive route to controlling the pandemic.

Before progressing any further:

Governments should:

- Be up front as to whether any systems are intended to be used long term, and design and consult accordingly.

- Establish clear, published criteria for the success of a system and for ongoing evaluation.

- Ensure legislation includes a time-limited period with sunset clauses or conditions under which use is restricted and any dataset deleted – and structures or guidance to support deletion where data has been integrated into work systems for example.

- Ensure legislation includes purpose limitation, with clear guidance on application and enforcement, and include safeguards outlining uses which would be illegal.

- Work through international bodies like the WHO, GAVI and COVAX to seek international agreement on vaccine passports and mechanisms to counteract inequalities and promote vaccine sharing.

Developers must:

- Engage in scenario-planning exercises that think ahead to how these tools

will be used after the pandemic. This should include consideration of how

these tools will be used in other contexts, whether those uses are societally

beneficial, and whether tools can be time-limited to mitigate potentially

harmful uses.

Introduction

The question of whether and how to implement COVID status certification schemes, or ‘vaccine passports’, has become an important topic across the globe. These schemes would allow differential access to venues and services on the basis of verified health information relating to an individual’s COVID-19 risk, and would be used to control the spread of

COVID-19.

There is a diversity of approaches being pursued across the world, for multiple purposes. Some countries and states are moving ahead unilaterally: Israel, Denmark and New York State are already rolling out COVID vaccine passports, and the United Kingdom is undertaking a

review into whether to implement a passport system.2

For use in international travel and tourism, groups like the Commons Project and the International Air Transport Association are developing applications for vaccine passports; the European Union has set out its plans for a Digital Green Certificate to enable travel within the bloc; and the World Health Organisation is developing a digital version of its International Certificate of Vaccination or Prophylaxis for use with COVID-19.

In this report, the Ada Lovelace Institute aims to clarify the key considerations for any jurisdiction considering whether and how to implement digital vaccine passports to control the spread of COVID-19.

Most of the evidence we received came from or focused on the United Kingdom, Europe and north America, so our requirements for socially beneficial vaccine passport schemes are likely to be particularly relevant to liberal democracies.

We use ‘vaccine passports’ as an imperfect umbrella

term to encompass digital certification schemes that use

one or more of vaccination record, test result or ‘natural immunity’

Defining ‘vaccine passports’

Finding the right phrase to describe these new forms of digital certification is difficult. ‘Passports’ may be more helpful than ‘certificates’ in that they imply that an individual’s status means something in terms of what they can access, rather than simply recognising that an event (a vaccination) has taken place. But they can also be confusing given conversations are happening about both international travel and domestic uses.

When schemes based on an individual having recovered from COVID-19 were first discussed, they were known as ‘immunity passports’ or ‘immunity certificates’. But the term ‘immunity’ was problematic for at least two reasons: proof of recovery from the disease was an imperfect proxy at best for immunity, with evidence still emerging about how protected a recovered patient might be; and the term ‘immunity’ itself has different meanings in individual and collective contexts (whether it protects an individual and to what extent, and whether it protects those they come into contact with).

Many countries and schemes, e.g. Israel’s domestic scheme and the European Union’s proposed scheme for travel, refer to ‘green pass’ or ‘green certificate’. This focuses on the authorisation part of the scheme – like a traffic light – rather than the health information aspect.

Most recently, ‘vaccine passports’ or ‘vaccine certification’ have become common. As described above, a variety of tests are now being used as part of existing and proposed systems, so the term can be misleading as it suggests that only vaccination will provide an individual with access and other benefits. Acknowledging this complexity, we have chosen to

use ‘vaccine passports’ as an imperfect umbrella term to encompass digital certification schemes that use one or more of vaccination record, test result or ‘natural immunity’.

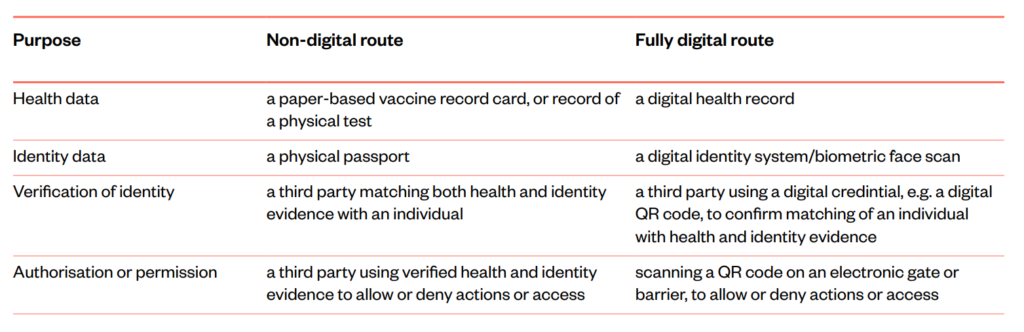

For the purposes of this study, a digital vaccine passport as defined here consists of four component functions and purposes:

- health information (recording and communication of vaccine status or test result through e.g. a certificate)

- identity information (which could be a biometric, a passport, or a health identity number)

- verification (connection of a user identity to health information)

- authorisation or permission (allowing or blocking actions based on the health and identify information).

Modelling individual risk will always require simplification of a messier underlying reality that involves missing or inaccurate information

This definition extends the function and purpose beyond a digital vaccination record, to enable healthcare providers to know which vaccine doses to administer when. Sharing this verified health information through a vaccine passport is intended to provide information about an individual’s COVID-19 risk, both to themselves and to others, and to assess that information to make decisions about access and movement.

Modelling individual risk will always require simplification of a messier underlying reality that involves missing or inaccurate information, and uncertainty in how to interpret the information available. The question is whether those proxies for risk, despite their flaws, can enable individuals and third parties to distinguish between individuals who are more or less at risk of being infected with and spreading COVID-19.

Most models currently focus on displaying binary attributes (yes/no) of some combination of four different types of risk-relevant COVID-19 information:

- A status based on medical process, evidenced through:

- vaccination records, including data, type and doses

- proof of recovery from COVID-19, e.g. receiving a positive PCR

test, completing the requisite period of self-isolation and being

symptom free.

- A status based on direct observation of correlates of risk, evidenced

through:- negative virus test results

- antibody test results.

Other schemes might provide a more granular or ‘live’ assessment of risk by incorporating information such as background infection rates, demographic characteristics of users, or users’ underlying health conditions. These schemes are not covered in this report, although many of the points below can also relate to models that provide a stratified assessment of risk and subsequently more differentiated access.

However we choose to identify them, vaccine passports must be considered as part of a wider sociotechnical system – something that goes beyond the data and software that form the technical application (or ‘app’) itself, and includes: data; software; hardware and infrastructure; people, skills and capabilities; organisations; and formal and informal institutions.3

Identifying these components highlights how any successful system needs to consider not just the technical design questions within the app itself, but how it interacts with wider complex systems. Vaccine passports are part of extensive societal systems, like a public-health system that includes test, trace and isolate services, behavioural guidance on mask wearing and social distancing, or a wider biometrics and digital ID ecosystem.

How any sociotechnical system should be designed, what use cases are appropriate, what legal concerns need to be considered and clarified, what ethical tensions are most relevant, what publics deem acceptable and legitimate, and what future risks any system runs, are all questions that will need to be resolved within the particular context policymakers and developers are operating in.

A brief history of health-based, differential restrictions and vaccine certification

Discussions of vaccine certification are not unique to COVID-19. They have been around for as long as vaccines themselves – such as smallpox in pre-independence India.4 The idea of ‘immunoprivilege’ – that citizens identified as having immunity against certain diseases would enjoy greater rights and privileges – also has a long history, such as the status of survivors of yellow fever in the nineteenth-century United States.5

Yellow fever is the most commonly referenced example of existing vaccine certification for a specific disease. The International Certificate of Vaccination or Prophylaxis (ICVP), also known as the Carte Jaune or Yellow Card, was created by the World Health Organisation as a measure to prevent the cross-border spread of infectious diseases.6

Although it dates back in some form to the 1930s, it has been part of the International Health Regulations since 1969 (and was most recently updated in 2005). The regulations remove barriers to entry for anyone who has been vaccinated against the disease. Even when travelling from a country where yellow fever was endemic, showing a Yellow Card would mean someone could not be prevented from entering a country because of that disease.4

There are some important differences between yellow fever and COVID-19: yellow fever vaccines are highly effective and long lasting, while COVID-19 vaccines are still being developed and there is not yet evidence to show how long they are effective for. Transmission is also different: yellow fever spreads via vectors (infected mosquitoes) rather than directly from person to person, which is why there are no global outbreaks of yellow fever and it is easier to control the disease.8

In May 2021, yellow fever is the only disease that is expressly listed in the International Health Regulations, meaning that countries can require proof of vaccination from travellers as a condition of entry. But there have been others, including smallpox (removed after the disease was eradicated), cholera and typhus, both removed when it was decided vaccination against them was not enough to stop outbreaks around the world. The certificate has, historically, been paper-based, but there had been proposals and advocacy to digitise the system even before

COVID-19.9

A brief history of COVID status certification

At the start of the pandemic, a number of countries demonstrated interest in some form of ‘immunity passport’ based on natural immunity and antibodies after infection with COVID-19 to restore pre-pandemic freedoms (including Germany and the UK, and a pilot in Estonia), but a

lack of evidence about the protection acquired through natural immunity meant few schemes were used in real-world scenarios.10

The WHO has shifted its stance by announcing plans to develop a digitally enhanced International Certification of Vaccination

In April 2020, the World Health Organisation (WHO) put out a statement saying there was ‘not enough evidence about the effectiveness of antibody-mediated immunity to guarantee the accuracy of an ‘immunity passport’ or “risk-free certificate”’, and that ‘the use of such certificates may therefore increase the risks of continued transmission’.11

The approval and roll-out of effective vaccines re-energised the idea of restoring personal freedoms and societal mobility based on COVID vaccinate passports. Israel implemented a domestic ‘Green Pass’ in February 2021,12 the European Commission published plans for a Digital Green Certificate in March 2021,13 and Denmark began using a domestic ‘Coronapas’ in April 2021.14

The WHO has shifted its stance by announcing plans to develop a digitally enhanced International Certificate of Vaccination and has established the Smart Vaccination Certificate consortium with Estonia. However, as of April 2021, it remains of the view that it ‘would not like to see the vaccination passport as a requirement for entry or exit because we are not certain at this stage that the vaccine prevents transmission’.15

IBM has launched Digital Health Pass,16 integrated with Salesforce’s employee management platform Work.com,17 and has worked with New York State to launch Excelsior Pass.18 CommonPass, supported by the World Economic Forum, and the International Air Transport Association (IATA)’s Travel Pass are both being trialled by airlines.19

The Linux Foundation Public Health’s COVID-19 Credentials Initiative and the Vaccination Credential Initiative, which includes Microsoft and Oracle, are pushing for open interoperable standards.20 A marketplace of smaller, private actors has also emerged offering bespoke solutions and infrastructures.21

In the UK, the Government initially appeared reluctant, saying it had ’no plans’ to introduce a scheme, and that such a scheme would be ’discriminatory’.22 Other ministers left the door open to digital passporting schemes when circumstances changed,23 and and the Government appeared to be keeping its options open by funding a number of startups piloting similar technology, tendering for an electronic system for citizens to show a negative COVID-19 test, and reportedly instructing officials to draw up draft options for vaccine certificates for international travel.24

There are intuitive attractions to the idea of a COVID vaccine passport scheme

As part of its roadmap out of lockdown in February, the Government announced a review into the possible use of certification.25 This was followed by a two-week consultation and an update in April announcing trials of domestic COVID status certification for mass gatherings, theatres, nightclubs and other indoor entertainment venues.26

For a comprehensive overview of international developments, see the Ada Lovelace Institute’s international monitor of vaccine passports and COVID status apps.

The hopes for vaccine passports

There are intuitive attractions to the idea of a COVID vaccine passport scheme, and particularly in the hope that a better balance could be found between economic activity and community safety, by allowing a more fine-grained and targeted set of restrictions than sweeping measures of national lockdowns. Such hopes are particularly located in the prospect of a silver bullet that may help return life to something resembling normal, after more than a year of social anxiety and economic damage.

A number of arguments have been put forward for the usefulness of

COVID vaccine passports, including:

- Public health: Those who are certified as unable to transmit the virus are allowed to take part in activities that would normally present a risk of transmission. Being able to take part in such activities, see family and friends and visit hospitality and entertainment venues will have a positive effect on wellbeing and mental health.

- Vaccine uptake: The use of certification to provide those who have been vaccinated with greater access to society could incentivise vaccination among those who are able to be safely immunised.

- Personal liberty: Enhancing the freedoms of those who have a passport to do things that would otherwise be restricted due to COVID-19 (always noting that granting permissions for some will, in relative terms, increase the loss of liberty experienced by others). This could have a particularly profound benefit for those facing extreme harm and isolation due to the virus, for example those suffering domestic abuse, or in care homes and unable to see relatives.

- Economic benefits: supporting industries struggling in lockdown (and the wider economy) by enabling phased opening, for example in entertainment, leisure and hospitality.

- International travel: a passport scheme will allow people to travel for business and pleasure, with economic benefits (particularly for the tourism industry) and social advantages (reuniting families or holidays).

Science and public health

The first question to ask of a COVID vaccine passport system is whether an individual’s status conveys meaningful information about the risk they pose to others

The foundation of any COVID status certificate or ‘vaccine passport’ is that it allows stratification of people by COVID-19 risk and therefore allows a more fine-grained approach to preserving public health, keeping the community safer with fewer restrictions. Vaccine passports allow only those who pose an acceptably lower risk to others to take part in activities that would normally present a risk of transmission, e.g. working in care homes, travelling abroad, or entering venues and events such as pubs, restaurants, music festivals or sporting fixtures.

Therefore, the first question to ask of a COVID vaccine passport system is whether an individual’s status, for example that they have been vaccinated, conveys meaningful information about the risk they pose to others? Does the scientific evidence base we have on COVID-19 vaccines, antibodies and viral testing, support making that link, and if so, how certain should we be about an individual’s risk based on those proxies?

The development and deployment of a significant number of viable vaccines in just over a year is a remarkable scientific achievement. Tests have also rapidly improved in quality and quantity, and scientific understanding of COVID-19 infection and transmission has improved greatly since the beginning of the pandemic. In spite of these inventions and innovations, unfortunately the novelty of the disease means the answers to significant questions are still uncertain.

Vaccination and immunity

Our knowledge of COVID-19 vaccine efficacy against different its strands and immunity following an infection continues to evolve. Key questions about vaccines include:

- What are the effect of vaccines on those vaccinated?

- What are the effect of vaccines on spreading the disease to others?

- What is the efficacy of vaccines against different emerging variants?

- What is the efficacy of vaccines over time?

Our expert deliberative panel expressed concern about developing any system of COVID vaccine passport based on proof of vaccination while so much is still unknown – as systems could be built on particular assumptions that would then change. Any system that was developed would have to be flexible enough to deal with emerging evidence.

One certainty is that no vaccine is currently entirely effective for all people. Although evidence is encouraging that the current COVID-19 vaccines offer strong protection against serious illness, vaccination status does not offer conclusive proof that someone vaccinated cannot become ill.

The evidence is even more emergent on the effect of vaccines on the transmission of COVID-19 from one person to another. Any public health argument in favour of introducing vaccine passports relies on evidence that someone being vaccinated would protect others, but this remains unclear.27

A vaccine can provide different types of immunity:

- Non-sterilising immunity, where an infected individual is protected from the effects of the disease but can still transmit it (and may instead have an asymptomatic case where previously they would have displayed symptoms).28

- Sterilising immunity, where a vaccinated person does not get ill themselves and cannot transmit the disease.

Experts in our deliberation identified a ‘false dilemma’ in discussions about the efficacy of these different types of immunity: even a population vaccinated with ‘non-sterilising’ immunity should still prevent the disease spreading, as infected individuals will have weaker forms of it and fewer ‘virions’ (infectious virus particles) to spread. Emerging evidence suggests that ‘viral load’ is lower in vaccinated individuals, which may have some effect on transmission, and one study (in Scotland) found the risk of infection was reduced by 30% for household members living with a vaccinated individual, but much remains unknown.29

An issue raised in the deliberation was that focusing on individual proof of vaccination might underemphasise the collective nature of the challenge. Vaccination programmes aim at (and work through) a population effect: that when enough people have some level of protection, whether through vaccination or recovery from infection, the whole population is protected through reaching herd immunity. Even following vaccination, the UK Government’s Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies offers caution: ‘Even when a significant proportion of the population has been vaccinated lifting NPIs [non-pharmaceutical interventions, like social distancing] will increase infections and there is a likelihood of epidemic resurgence (third wave) if restrictions are relaxed such that R is allowed to increase to above 1 (high confidence)’. This pattern of vaccination and infection may be occurring in Chile, where high vaccination rates have been followed by a surge in cases.30

Different vaccines have different levels of efficacy when it comes to protecting both the person receiving the vaccination and anyone they come into contact with. This is partly due to vaccines having different levels of effectiveness, based on differently underlying technologies.

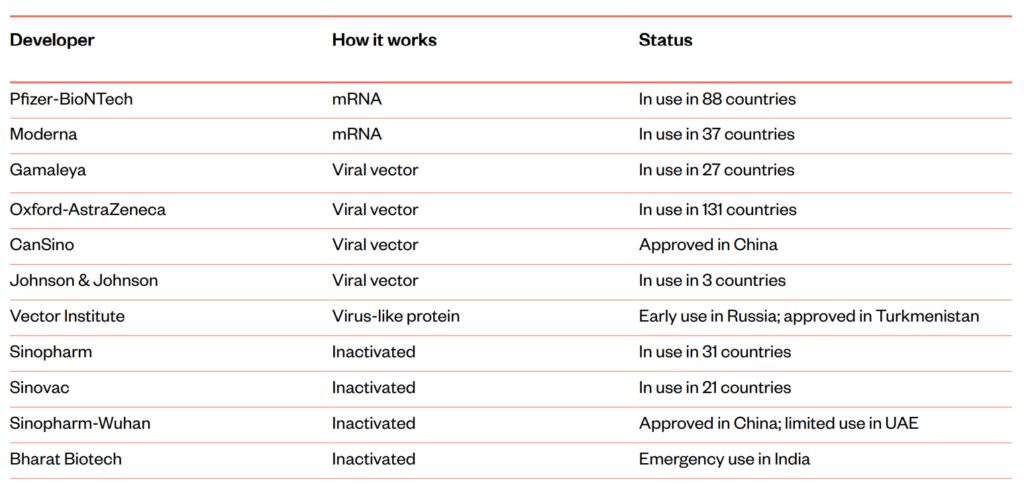

As of May 2021, 12 different vaccines are approved or in use around the world, utilising messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA), viral vectors, inactive coronavirus, and virus-like proteins:31

Vaccines approved for use, May 2021

Different levels of efficacy will also be partly due to different individuals responding differently to the same vaccine – the same vaccine may be effective in protecting one recipient and less so in protecting another.

The efficacy of the vaccines may change with different variants of the disease. There are concerns that some vaccines, for example the current Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine, may be less effective against the so-called South African variant.32 There will continue to be mutations in COVID-19, such as the E484K mutation which has been found in the Brazilian, South African and Kent strains of the disease (this is an ‘escape mutation’ which can make it easier for a virus to slip through the body’s defences) and the E484Q and L425R mutations present in many cases in India.33 Such mutations make understanding of vaccination effects on individual transmission a moving target, as vaccines must be assessed against a changing background of dominant strains within the population.

Booster vaccinations against variants may help manage the issue of strains. It is possible these may be necessary, as the efficacy of vaccines against any strain may change over time; the WHO has said, it is ‘too early to know the duration of protection of COVID-19 vaccines’.34 With the disease only just over a year old and the vaccines having deployed only in the last few months, it will be some time before conclusive evidence is available on this.

Any vaccine passport system would need to be dynamic – taking into account the differing efficacy of different vaccines, known differences in efficacy against certain variants and the change in efficacy over time – as well as representing the effect of the vaccine on the individual carrying a vaccine passport.

There are also questions about any lasting immunity acquired by those recovering from COVID-19. The WHO has noted that while ‘most people’ who recover from COVID-19 develop some ‘period of protection’, ‘we’re still learning how strong this protection is, and how long it lasts’.35

Inclusion of testing

A number of COVID vaccine passport schemes in development (and the UK Government’s review into what it calls COVID status certification) may allow a combination of three characteristics to be recorded and used in addition to vaccination: recovery from COVID-19, testing negative for COVID-19, or testing positive for protective antibodies against

COVID-19.

We can group these characteristics into statuses based on medical process, and those based on medical observation.

Status based on medical process includes vaccination status and proof of recovery from COVID-19. In both cases, a particular event – recovering from an infection or having a vaccination – that might have some impact on an individual’s immunity is taken as a proxy for them posing less risk. As described above, the potential efficacy of this must be understood in the context of what remains unknown about an individual’s ability to spread the disease, their own immunity and the change in their immunity over time.

Status based on medical observation – or direct observation of results correlating to risk – includes two forms of testing: a negative test result for the virus, or a positive test result for antibodies that can offer protection against COVID-19.36 Incorporating robust tests might provide a better, though very time-limited, measure of risk (the biggest challenges to this would be practical and operational). Status based on test results would also avoid the need for building a larger technical infrastructure, particularly one involving digital identity records. But current testing mechanisms do have drawbacks.

There are two main kinds of diagnostic tests that could be used for negative virus test certification:

- Molecular testing, which includes the widely used polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests, detect the virus’s genetic material. They are generally highly accurate at detecting negative results (usually higher than 90%), but their exact predictive value depends on the background rate of COVID-19 infection,37 and depends on the point in the infection that the test is taken.38 These tests often detect the presence of coronavirus for more than a week after an individual stops being infectious. They also need to be processed in a lab – during which time an individual may have become infected and infectious.

- Antigen testing, which includes the rapid lateral flow tests used in the UK Government’s mass-testing programmes, detect specific proteins from the virus. If someone tests positive, the result is generally accurate – but as these types of test only detect high viral loads, positive cases can be missed (a ‘false negative’) particularly when self-administered. Certificates based on antigen tests are likely to have a high degree of inaccuracy – tests might be useful in screening and denying (a ‘red light’), rather than allowing (a ‘green light’ test), entry to individuals at a specific point in time. They are unlikely to be useful for any kind of durable negative certification.

Antibody tests, meanwhile, confirm that an individual has previously had the virus. There are two sources of variability from these tests. First, people may have variable antibody response when they are infected with COVID-19 – while most people infected with SARS-CoV-2 display an antibody response between 10 and 21 days after being infected, detection in mild cases can take longer, and in a small number of cases antibodies are not detected at all.39 Second, the tests themselves are not completely accurate, and the accuracy of different tests varies.40

It also remains unclear how an individual antibody test result should be interpreted. The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control advises that it is currently unknown, as of February 2021, whether an antibody response in a given infected person confers protective immunity, what level of antibodies is needed for this to occur, how this might vary from person to person or the impact of new variants on the protection existing antibodies confer.41 The longevity of the antibody response is also still uncertain, but it is known that antibodies to other coronaviruses wane over time.42

Questions remain as to how viable rapid and highly accurate testing is, particularly those that can be completed outside a lab setting. Although a testing regime allowing entry to venues could avoid a number of the challenges associated with using vaccination status (extensive technical infrastructure and access to health data, possible discrimination against certain groups) it also provides practical and logistical challenges – from administering such tests for access to a sporting event or hospitality venue, to the feasibility of regularly testing children – as well as there being uncertainty around the accuracy of tests.

Risk and uncertainty

At a time when uncertainty – about vaccine efficacy, when life will return to ‘normal’ and much else besides – is endemic, it is natural that politicians, policymakers and the public alike are grasping for certainty. There may be a danger in seeing COVID vaccine passports as a silver bullet returning us quickly to normality, with passports suggesting false binaries (yes/no, safe/unsafe, can access/cannot access) and false certainty, at a time when governments need to be communicating uncertainty with humility and encouraging the public to consider evidence-based risk. Our expert panel raised concerns that the UK Government saying it was ‘led by the science’ brought disadvantages, encouraging a simplistic view of it being infallible and squeezing out space for nuance and debate.

Conveying a proper sense of uncertainty and risk will be important as individuals make decisions about their own health that may also have an impact on collective public health. For example, if I have been vaccinated, but know there is a chance it may not be fully effective, how does that change how I assess the risk to me in engaging in certain behaviours?

What information will I need to also assess my risk of spreading the disease to others? Is it useful for a venue that admits me to understand that a passport may provide a false sense of certainty that I do not have or cannot easily spread the disease?

Any reliance on proof that the process of vaccination has been completed will also require careful consideration about the actual change in risk as a result of that system: experts raised the risk that use of passports could increase the spread of the disease, as individuals who believe themselves to be completely protected engage in riskier behaviour. A review of the limited evidence so far suggests vaccine passports could reduce other protective behaviours.43

While vaccine passports could make people more confident in some areas, for example by providing reassurance to vulnerable people who have been isolating, it could also slow down the return to normality by suggesting to some that their fellow citizens are a permanent threat.

Creating categories of ‘safe’ and ‘unsafe’ that could continue to keep risk salient in people’s minds even once the risk is reduced (for example a risk closer to that of flu: dangerous but not overwhelmingly so) could be counterproductive to reopening and restarting society and the economy.

Recommendations and key concerns

If a government wants to roll out its own COVID vaccine passport system, or permit others to do so, there are some significant risks it needs to consider and mitigate from the perspective of public health.

The first is that vaccine passport schemes could undermine public health by treating a collective problem as an individual one. Vaccine passport apps could potentially undermine other public health interventions and suggest a binary certainty (passport holders are

safe; those without are risky) that does not adequately reflect a more nuanced and collective understanding of risk posed and faced during the pandemic. It may be counterproductive or harmful to encourage risk scoring at an individual level when risk is more contextual and collective – it will be national and international herd immunity that will offer ultimate

protection. Passporting might foster a false sense of security in either the passported person or others, and increase rather than decrease risky behaviours.35

The second is the opportunity cost of focusing on COVID vaccine passport schemes at the expense of other interventions. Particularly for those countries with rapid vaccination regimes, there may be a comparatively narrow window where there is scientific confidence about the impact of vaccines on transmission and enough of a vaccinated population that it is worth segregating rights and freedoms. Once there is population-level herd immunity or COVID-19 becomes endemic with comparable risks to flu, it will not make sense to differentiate and a vaccine passport scheme would be unnecessary.

COVID vaccine passport schemes bring political, financial and human capital costs that must be weighed against any benefits. They might crowd out more important policies to reopen society more quickly for everyone, such as vaccine roll-out, test, trace and isolate schemes, and other public health measures. Focusing on vaccine passports may give the public a false sense of certainty that other measures are not required, and lead governments to ignore other interventions that may be crucial.

If a government does want to move forward, it should:

Set scientific preconditions. To move forward, governments should have a better understanding of vaccine efficacy and transmission, durability and generalisability, and evidence that use of vaccine passports would lead to:

- reduced transmission risk by vaccinated people – this is likely to involve

issues of risk appetite, as the risk of transmission may be reduced but will

probably not be nil. - low ‘side effects’ – that passporting won’t foster a false sense of security in either the passported person or others, which might lead to an increase of risky behaviours (not following required public health measures), with a net harmful effect. This should be tested, where possible, against the benefits of other public health measures.

Communicate clearly what certification means. Whether governments choose to issue some kind of COVID status certification, sanction private companies to do so or ban discrimination on the basis of certification altogether, individuals will make judgements based on the health information underlying potential schemes in informal settings such as gathering with friends or dating.

Governments must clearly communicate the differences between different types of certification, the probabilistic rather than binary implications of each, and the relative risks individuals face as a result.

To support effective communication, governments, regardless of whether they themselves intend to roll-out any certification scheme, should undertake further quantitative and qualitative research of different framings and phrasing on public understanding of risk, to determine how best to communicate efficacy of each kind of certification.

Purpose

It is important that governments state

the purpose and intended effect of any COVID vaccine

passport scheme

It is important that governments state the purpose and intended effect of any COVID vaccine passport scheme, to give clarity both to members of the public as to why the scheme is being introduced and to businesses and others who will need to implement any scheme and meet legal requirements in frameworks like data protection.

It is hard to model, assess or evaluate vaccine passports at a general level so governments will need to state the purpose of any system, what it will be used for and, crucially, what will not be included in any such system, i.e. if particular groups will be exempt, or if particular settings will

be off-limits.

Use cases

In debates, particular use cases have focused on international travel, indoor entertainment venues and employment.

International travel

Some organisations, like the Tony Blair Institute, have argued that the way to navigate allowing people to travel internationally again will be for travellers to show their current COVID-19 status – either a proof of vaccination or testing status.45 Already, many countries require proof

of vaccination, proof of recovery or negative COVID-19 test results as a requirement for entry. Much of the industry focus for vaccine passports has been on airports and international travel.

International travel already has existing norms around restricting entry to places at specific checkpoints, based on information contained in passports, and the infrastructure to support such a system. Further, passports are already linked to biometrics and sometimes to digital

databases, as with the USA’s ESTA visa.

In these circumstances, countries will have an obligation to provide their citizens with proof of vaccination in order to allow them to travel to countries that require it. Once a system is in place to allow proof of vaccination for travel to some countries, the marginal cost for further

countries to require proof lowers, and there is a normalised precedent set by other travellers. It is easy to see international COVID vaccine passport schemes come into place even if initially only a small number of countries strongly support them.

The WHO maintains that they do not recommend proof of COVID-19 vaccination as a condition of departure or entry for international travel.46 However, the WHO is consulting on ‘Interim guidance for developing a Smart Vaccination Certificate’.47 The question of COVID vaccine passport systems for international travel seems now to be resolving around standard-setting, ensuring equity and establishing the duration of the scheme, rather than whether such schemes should exist at all.

Indoor entertainment venues

Indoor entertainment venues such as theatres, cinemas, concert venues and indoor sports arenas all have similar characteristics. with large groups of people coming together and remaining seated or standing in close proximity for hours. This means they are both higher risk and discretionary activities, which many countries have focused on as an opportunity to allow opening, or to reassure customers in attending.

Examining the use case of opening theatres only to those with some form of COVID status certification highlights how many of the logistical issues might play out in a particular context. First, there will be other activities related to the theatre trip – particularly using public transport

to reach the venue, or meeting in a pub beforehand. One of the UK Government’s scientific advisory bodies considered these may pose a higher transmission risk than the activity itself.48

Second, there will be practical and logistical challenges at the theatre. Because tickets are sold through secondary sellers as well as by the venue, it is likely that status could only be checked at the theatre on arrival. Any certification system would need to be available to all visitors,

including international ones. If tests at the venue could also be used to permit entry, there would be logistical challenges (for example, where would the tests be administered, and by whom?) that could make the cost prohibitive for theatres.

The increasing role many theatres and arts organisations play in their community could also suffer. Disparities in vaccine uptake, particularly between communities of different ethnicities, could mean COVID vaccine passports are counterproductive to theatre’s goals of inclusivity and acting as a shared public space. According to one producer, ‘the application of vaccine passports for audiences are likely to fundamentally alter a relationship with its local community.’49

Others in the arts,50 sport and hospitality acknowledge these challenges but believe they can be overcome. In the UK, a number of leading sports venues and events – including Wimbledon (tennis), Silverstone (motor racing), the England and Wales Cricket Board and the main football and rugby leagues – have welcomed the Government’s review and would welcome early guidelines to support planning.51

Employment (and health and safety)

Employment-related use cases discussed in the media include proposals that frontline workers, particularly in health and social care, would have to be vaccinated to work in certain settings (especially in care homes). Other employers – such as plumbing firm Pimlico Plumbers in the UK – have suggested they may only take on new staff who have been vaccinated.52 Staff may feel more comfortable returning to work, knowing that colleagues have been vaccinated. Therefore it’s an important use case for governments to address (and may have to grapple with themselves, given they are also employers).

The situation will vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. In the UK, the Health and Safety at Work Act (1974) requires employers to take care of their employees and ensure they are safe at work. Given that, employers might think it prudent to ask themselves whether vaccination could play a role in that process.

The ‘hierarchy of controls’ applies in workplace settings in the UK, and may also be a helpful guide for other jurisdictions.53 Controls at the top of the hierarchy are most effective in protecting against a risk and should be prioritised:

- Elimination: Can the employer eliminate the risk by removing a work activity or hazard altogether? This is not currently possible in the case of COVID-19. Vaccination and even testing could not guarantee this, given the still-emerging scientific evidence on vaccine impact on transmission, and possible false negatives in testing.

- Substitution: Can the hazard be replaced with something less hazardous? Working from home rather than at the place of work would count as a substitution.

- Engineering controls: This refers to using equipment to help control the hazards, such as ventilation and screens.

- Administrative controls: This involves implementing procedures to control the hazards – with COVID-19, these might include lines on the floor, one-way systems around the workplace and social distancing.

- Personal protective equipment (PPE): This is the last line of defence, to be tried only if measures at all other levels have been tried and found ineffective. Even if one argued that a vaccine counted as PPE, it would only be a last line of defence, and no substitute for employers taking other actions first.

In most settings, it is likely to be difficult for an employer to argue that vaccination could be a primary control in ensuring the safety of most workplaces. Other measures, such as social distancing, better ventilation and allowing employees to work from home, are higher up the hierarchy and likely to deliver some benefits.

There may be some workplace settings where different considerations might apply – for example, in healthcare. The UK Government has suggested that care home staff might be required by law to have a COVID-19 vaccination, and is consulting on the issue.54 Many have

cited hepatitis B vaccination as a precedent. However, this is not legally required in the way many people have understood – it is a recommendation of the Green Book on immunisation that many health providers have considered proportionate and therefore require their staff

to have as part of their health and safety guidance.55 This will vary across workplaces: if an employer carried out a risk assessment that found that employees had to have a vaccination, proportionality would depend on the quality of the risk assessment.56 There may be other examples of measures being considered proportional in some work settings but not in others – for example, regularly testing staff working on a film or television production might be sensible, given that any outbreak would shut the production down at huge cost, but not in an office, where other measures can be taken.

What would happen if an employer tried to implement a ‘no jab, no job’ policy, where someone could not work without a vaccine? The UK’s workplace expert body, ACAS (the Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service), recommends that employers should:

- not impose any such decision, but discuss it with staff and unions (where applicable)

- support staff to get the vaccine, rather than attempting to force them to do so

- put any policy in writing and ensure it is in line with existing organisation policies (for example, disciplinary and grievance policies), and probably do so after receiving legal advice.57

Discussions with employees should also surface any other concerns. These may include scope creep – employees might be concerned that employers will want further information – including why an employee might not be able to receive a vaccine – which might require disclosing personal information (pregnancy for example) or perhaps other personal data (such as venues an employee had checked into). Once an employer has invested in a system, there may be concerns as to what else they might want to use it for – there are concerns about growing workplace surveillance in general,58 especially given the changes made to working patterns by the pandemic. There may also be concerns that if an employer tried to require vaccination, they could also require (for example) that employees return physically to the office rather than being able to work from home.