It’s complicated: what the public thinks about COVID-19 technologies

Lessons developers and policymakers must learn from the public about COVID-19 technologies.

6 July 2020

Alongside the horror of the first wave of COVID-19 engulfing the UK, we’ve witnessed the complicated interplay between policy and technology, and how the lure of techno-solutionism can obscure the very real challenges of using tech to support the pandemic response. Now, as the effects of easing lockdown are measured and analysed, Government will be considering a more targeted approach to restricting people’s movements based on live assessment of risk at a local, or even individual, level.

Technology can certainly play a central role in getting people back to normal life safely, and a variety of COVID-19 technologies are already on the table – from contact tracing apps to nascent work on ’immunity’ certificates or health status apps.

It is vital in tech development cycles – even in a crisis – to make opportunities to reflect on the purpose of the technology, its impacts and unintended consequences. As the Track and Trace regime gets up to full capacity, it is responsible to recoup some of the effort and resource poured into the delayed app into an effective, proportionate technological approach to a post-lockdown/pre-vaccine society.

As we have seen with centralised contact tracing, underplaying the very real challenges of these technologies will not reduce them. COVID-19 technologies must be built with public legitimacy because – put bluntly – if they are not, they won’t work. Each app will require people to adopt it, to use it and to adhere to it. If it’s not deemed legitimate, proportionate, safe and fair it will fail.

And there’s a greater risk – that of ‘one bad app’. Failure won’t just be dismissed as one poor product. If Governments develop, commission, and put their weight behind tech tools as instruments for public health, failing to live up to the high standard we set for healthcare provision will diminish faith in public health strategy. Badging the contact tracing app as NHS brings blowback on the NHS, and it undermines faith in future tech tools that could prove lifesaving.

Tools of this societal importance need to be shaped by the public. Given the technicality and complexity, that means going beyond surface-level opinions captured through polling and focus groups and creating structures to deliberate with groups of informed citizens. That’s hard to do well, and at the pace needed to keep up with policy and technology, but difficult problems are the ones that most need to be solved.

To help bring much-needed public voices into this debate at pace, we have drawn out emergent themes from three recent in-depth public deliberation projects, that can bring insight to bear on the questions of health apps and public health identity systems.

While there are no green lights, red lines – or indeed silver bullets – there are important nuances and strongly held views about the conditions that COVID-19 technologies would need to meet. The report goes into detailed lessons from the public, and I would like to add to those by drawing out here aspects that are consistently under-addressed in discussions I’ve heard about these tools in technology and policy circles.

- Trust isn’t just about data or privacy. The technology must be effective – and be seen to be effective. Too often, debates about public acceptability lapse into flawed and tired arguments about privacy vs public health; or citizens’ trust in a technology being confused with reassurances about data protection or security frameworks against malicious actors. First and foremost people need to trust the technology works – they need to trust that it can solve a problem, that it won’t fail, and it can be relied on. The public discussion must be about the outcome of the technology – not just its function. This is particularly vital in the context of public health, which affects everyone in society.

- Any application linked to identity is seen as high-stakes. Identity matters and is complex – and there is anxiety about the creation of technological systems that put people in pre-defined boxes or establishes static categories as the primary mechanisms by which they are known, recognised and seen. Proportionality (while not expressed as such) runs deep in public consciousness and any intrusion will require justification, not simply a rallying call for people to do their duty.

- Tools must proactively protect against harm. Mechanisms for challenge or redress need to be built around the app – and indeed be seen as part of the technology. This means that legitimate fears that discrimination or prejudice will arise must be addressed head on, and lower uptake from potentially disadvantaged groups that may legitimately mistrust surveillance systems must be acknowledged and mitigated.

- Apps will be judged as part of the system they are embedded into. The whole system must be trustworthy, not just the app or technology – and that encompasses those who develop and deploy it and those who will use it out in the world. An app – however technically perfect – can still be misused by rogue employers, or mistrusted through fear of government overreach or scope creep.

- Tools are seen by the public as political and social. Technology developers need to understand that they are shifting the social-political fabric of society during a crisis, and potentially beyond. Tech cannot be decoupled or isolated from questions of the nature of the society it will shape – solidaristic or individualistic; divisive or inclusive.

So what should those working on immunity passports, health status apps, contact tracing tools – or other formulations of COVID-19 tech take from this?

I would make a few recommendations, building on these public deliberations, to the tech developers and policymakers:

- Tread carefully and slowly. Acknowledge the anxieties and risks – don’t downplay them, monitor them and work in the open. Anticipate and design in responses to harms rather than dismissing them.

- Build in-depth public deliberation in from the start. Now is a time where the public are deeply engaged in this issue, and following policy and news closely to consider how to manage their lives and their risks. If you give people time to talk to experts on an equal footing, they have nuanced and contextualised opinions.

- Understand that apps must be intertwined with policy decisions. Teams cannot be decoupled or operate purely on the tech without interactions with public health decisions, and with policy strategies. The public will engage with technology through the social, behavioural and governance contexts they are embedded in.

- Develop tools in the open, welcome feedback and set up independent research. It is not failure to acknowledge difficulties and welcome scrutiny. Trust will be greater if a plurality of organisations has engaged in development and support deployment, and wrong moves will be identified swiftly, saving time, money and political capital.

State-sponsored apps that monitor citizens movements and contacts, or that link private health information to a form of public health identity (PHI), would have been unthinkable until a few months ago. They are inherently controversial, raising not just technical and clinical issues, but posing deep societal risks as well.

Contemplating their deployment is justifiable only in the face of the grave threat we all face, but – as we have seen in countless other cases – once tech is out of the box, it’s hard to put back. We must bring in public voices to contemplate impacts on our society now, and consider how COVID-19 apps might reshape society after the crisis, before emergency measures become permanent incursions.

-> Watch the Ada Lovelace Institute video ‘Convening diverse voices: why we use public deliberation in our work’

Related content

The Citizens’ Biometrics Council

Bringing together 50 members of the UK public to deliberate on the use of biometrics technologies like facial recognition.

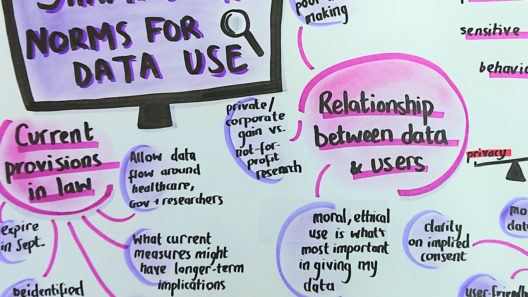

A rapid online deliberation on COVID-19 technologies: building public confidence and trust

Considering the question: ‘What would help build public confidence in the use of COVID-19 exit strategy technologies?’