A rapid online deliberation on COVID-19 technologies: building public confidence and trust

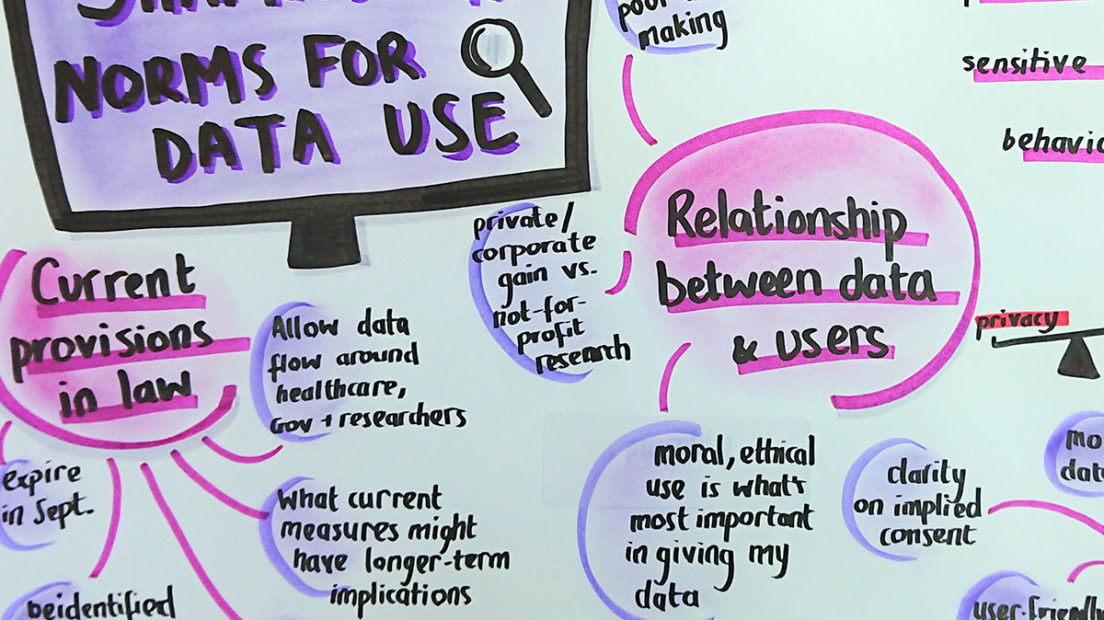

Considering the question: ‘What would help build public confidence in the use of COVID-19 exit strategy technologies?’

12 June 2020

Reading time: 7 minutes

For the last month of lockdown, we’ve been running a ‘rapid online deliberation’ on COVID-19 technologies, using the principles of deliberative democracy to examine the social and ethical implications emerging from the uses of symptom tracking, digital contact tracing and immunity certification to slow the spread of the virus and enable economic recovery.

Working with Traverse, Involve and Bang the Table, we undertook just over nine hours of deliberation through seven virtual workshops over a period of three weeks. We already have a broad public engagement programme at the Ada Lovelace Institute – you can see more on our health data citizen juries, as well as our Citizens’ Biometrics Council – supporting our belief that inclusive public deliberation can bring societal legitimacy to emerging technologies.

This project was unique in several ways, and presented distinct opportunities as well as challenges. Ordinarily public deliberation involves workshops (usually face to face) and takes place over weeks or months. It brings people together across different backgrounds, and creates time for reflection. But within the constraints of a faster–paced policy cycle, as we’ve experienced in lockdown – and with the additional challenges of social isolation – the tried-and-tested methods for doing public deliberation weren’t going to work.

The design challenge

We understood from the outset of the project that we had a design challenge – how best can we (and to what extent is it realistic to) stay true to deliberative principles in a virtual setting? Combining our expertise in convening, public deliberation and technology tools, we settled on convening seven workshops over a period of three weeks on a Zoom platform, replacing live presentations with five virtual experts and online Q&A, and live workshops with online chat. Talking to a demographically diverse group of 30 citizens (who, in line with best practice, were paid for their participation), we were able to create time for expert input with reflection and journaling in between, enabling effective exploration of questions at pace.

The three biggest challenges were:

- The paradox of public engagement: First, lockdown poses new challenges for those seeking to understand informed public perspectives. I call this ‘the paradox of public engagement’; uncertain times demand collective intelligence and a range of diverse perspectives of input but can also throw up new barriers and challenges for doing deliberation well . Against a backdrop of organisations calling for deliberative public engagement, we decided to pilot, prototype and learn from a practical question that responded to the pressures of the moment: ‘What would help build public confidence in the use of COVID-19 exit strategy technologies?’. Our experience – more on this later – was that people brought their own valuable and diverse experiences of lockdown with them into the ‘virtual’ room.

- A shortened, faster-paced policy and news cycle: Second, the fast-paced news and policy cycle undoubtedly shifted the pace at which the deliberation happened – interjected into our short deliberation were moments in the media and public consciousness that shaped and informed people’s reflections on the evidence base, on questions of social solidarity and personal responsibility, equity, justice and fairness – the beginning of the Isle of Wight trial, the Dominic Cummings revelations and the death of George Floyd. Insights from the deliberation reflect a wider, pronounced debate about power and privilege underway in society: calls that the use of COVID–19 technologies should not become, in the words of one citizen, a ‘gateway to privilege’.

- Examining values at a time of uncertainty: As is good practice in deliberation, we explored the values that should shape and inform policymaking processes. Notable in this COVID-19 deliberation is how sharp the contrasts are – there have always been tensions, for instance, between personal freedoms and safety/security, but the experience of lockdown has brought that into focus. As a deliberative process it was fascinating to hear people think through and grapple with some of these tensions – while they felt strongly that the use of a contact tracing app should not be mandatory, many people were still clear that people had a duty or responsibility to act with solidarity – with the sense that ‘we are all in this together’. And events in wider society changed opinions: while the citizens began with a strong sense of social solidarity, that shifted as coverage of Dominic Cummings’ journey to Durham substantially undermined the citizens’ sense of trust and confidence in public institutions’ ability to use technologies in an equitable and fair way.

Limitations to this approach

The rapid online deliberation approach is not without its limitations. There are very practical constraints on plenary dialogue across groups – often the standout feature of face–to–face public deliberation. Where there is substantive difference of opinion or a need to build trust across the group going into a deliberative process on a particular issue – where coming to a consensus or a meaningful resolution requires a process of several weeks and months, not days – the methodologies would need to be adjusted. (Such as issues where people are likely to have entrenched and/or very oppositional views – for instance, on polarising issues such as abortion or Brexit.) There are also intersectional inequality considerations (the underrepresentation of marginalised groups who are disadvantaged in multiple contexts) raised by social and digital exclusion. None of these limitations should be overlooked, and as with any approach to public engagement, whether online deliberation is the right method will be determined by the specific context and purpose of the process.

Trust in technologies, or trust in people, organisations’ and systems’ use of technologies?

The frame ‘trust in technologies’ (a term often bandied around uncritically) is a conflation of many different aspects of technology’s relationship with society, and this was unpacked by a number of conversations in the group.

A key theme from the deliberations was that it is the trust and confidence in the systems, of which technologies can only be one useful aspect, that shapes effective deployment, uptake and support for technologies. Towards the end of the process, citizens articulated a genuine concern that voluntary uptake of any technology solution or NHSX app would be undermined by a lack of public confidence – and posed the question: ‘How do we create a sense of solidarity and unity in the nation again, rebuilding trust for people to use and deploy technologies effectively?’

The citizens recognised the extent to which technologies and data deployed to ameliorate societal problems require whole-systems thinking. And that being able to interrogate the evidence base for technologies is critical to understanding their usefulness and effectiveness both as a digital tool, and in terms of how they might function in the context of a broader public health strategy.

They also signalled the importance of recognising the limitations of a technology solution, signposting to the importance of ensuring humans were ‘in the loop’ on the use of technology. They identified the need for adequate mental health and other support to those told to self-isolate, for instance, and recognised that app notifications would not impact everyone equally, highlighting the importance of economic protections to ensure effective use.

Many people stressed the importance of state provision of support, so that those told to isolate are not placed into a position where they have to choose between their need to earn money and their own or others’ safety. Observations also highlighted the importance of provisions and a wider communications strategy to protect against misuse of the process, scamming and malicious use.

Deliberating online reminded everyone involved that life is complex, non-linear and messy (especially at this unprecedented time, when we are adjusting to iterative ‘new normals’), and that the life experiences people bring to the table deliver important perspectives to policy decisions that affect all our lives – particularly those involving technology.

We will be sharing our emerging findings through forthcoming webinars, virtual workshops and a report.

Register for Deliberating rapidly and online about COVID-19 technologies – a webinar sharing the findings of this work on Thursday 25 June, 2020, 12:30-2pm.

Image credit: @sketch_skye

Related content

Why we cannot afford to leave technology to the experts – the case for public engagement at times of crisis

Discussing the profound societal challenges raised by developing technologies as central to government strategies in responding to COVID-19.

Deliberating rapidly and online about COVID-19 technologies

The second of two events sharing what we learned from a rapid online deliberation project to explore public attitudes to COVID-19 exit strategies.