Rapid, online deliberation on COVID-19 technologies

Rapid, online deliberation with 28 members of the public on COVID-19 exit strategies.

Project overview

Throughout May 2020, while the UK was in lockdown as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, together with Traverse, Involve and Bang the Table, we conducted rapid, online deliberation with 28 members of the public on COVID-19 exit strategies.

Based on the principles of good deliberative practice, the aim was to test a new engagement methodology that we hope will prove beneficial when traditional methods for public deliberation are not possible.

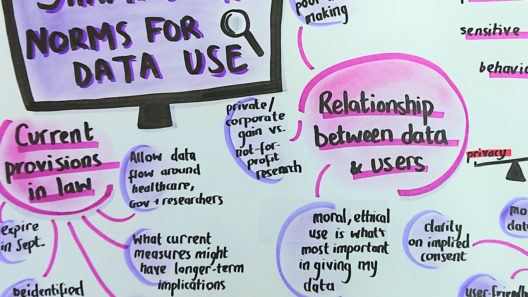

For this deliberative trial, we looked at the most topical subject matter at the time: how COVID-19 exit strategies are shaping or changing the way the public thinks and feels about areas such as privacy, trust, solidarity and human rights.

The focus was on citizens’ changing relationship with these norms as a result of the deployment of data and digital technologies in the pandemic response.

To emerge from the process, this mini public provided four strong steers on how to build COVID-19 technologies with legitimacy, remain pertinent to current concerns:

- Provide the public with a transparent evidence base. A lack of transparency,

particularly the limited information about the first Isle of Wight trial, generated

suspicion and distrust. The public would like to see clear and accessible

evidence on whether technologies are effective, and under what conditions. People want to have confidence that lives would be saved and expect

easily accessible information about aspects like the evolving health context

or relationships with commercial providers - Offer independent assessment and review of the technology. The

question of who is making judgements is important to the public, and trust

in decision-makers can be fragile. Trust can be strengthened with the inclusion

of independent reviewers, assessors and evaluators to shape the development

of the technology. - Clarify boundaries on data use, rights and responsibilities. Wanting

independent oversight doesn’t negate the desire for clarity on users’ data rights.

It must be easy to know and clearly justify what data would be held, by whom,

for what purpose, and for how long. - Proactively address the needs of, and risks relating to, vulnerable groups.

Support must be built in for people who may have additional vulnerabilities

or be rendered vulnerable as a result of the pandemic. A public health

technology must enable equal access and equal distribution of benefits;

protect against the surveillance, or profiling of, different demographic groups;

and ensure that new tools like immunity certificates do not become a gateway

to privileges.

The report, Confidence in a crisis? published on 17 August 2020, at a crucial moment pre-roll out of the second iteration of the NHS contact tracing app, draws from the findings of this deliberation, as well as supporting research. It includes a 10-point checklist for the Government, policymakers and tech developers grappling with this tricky next phase, which will help design and deliver COVID-19 technologies with public legitimacy built in.

The case for public engagement at times of crisis

In times of crisis, when decisions are being taken quickly, and the world is changing rapidly around us, public involvement is more important than ever. While it may feel more challenging to achieve in the circumstances of lockdown, it is possible, and deeply needed.

As the Nuffield Council on Bioethics and Involve have already argued, it is welcome that the government has been guided by scientific advice, but science or technology in isolation cannot determine the choice of strategies, or determine which risks are worth running.

As engagement practitioners and researchers, we believe we cannot afford to leave technology to the experts and we have seen first hand the value of involving the public in decision-making processes.

The process of running rapid, online deliberation

We endeavoured to run this project as openly as possible as we believe, during a time of national crisis, in particular, it’s essential that researchers, policymakers, and the public share lessons and learn from each other.

Each week Traverse published a short piece on the lessons learned:

- Designing a rapid process: lessons from the setup phase

- Running online discussions: lessons from week one

- Creating a buzz online: lessons from week two

And we’ve co-authored the following report outlining our learning about the process of running rapid, online deliberation designed to involve the public in the policy decision-making process as it evolves on a daily basis.

We ran the project independently – it wasn’t commissioned by government or the NHS – but rather funded and supported by the organisations involved who believe in the importance of the work.

Project publications

Confidence in a crisis?

Findings of a public online deliberation project on attitudes to the use of COVID-19 related technologies for transitioning out of lockdown

Related content

What place should COVID-19 vaccine passports have in society?

Findings from a rapid expert deliberation to consider the risks and benefits of the potential roll-out of digital vaccine passports

Checkpoints for vaccine passports

Requirements that governments and developers will need to deliver in order for any vaccine passport system to deliver societal benefit

A rapid online deliberation on COVID-19 technologies: building public confidence and trust

Considering the question: ‘What would help build public confidence in the use of COVID-19 exit strategy technologies?’

Why we cannot afford to leave technology to the experts – the case for public engagement at times of crisis

Discussing the profound societal challenges raised by developing technologies as central to government strategies in responding to COVID-19.