An eye on the future

A legal framework for the governance of biometric technologies in the UK

29 May 2025

Reading time: 110 minutes

This report is supported by a policy briefing which summarises the key findings.

How to read this report

If you are a policymaker:

- This report makes the case for a comprehensive, legislatively-backed biometrics governance framework in the UK. For a brief overview of the report, read the ‘Executive summary’, ‘Key recommendations’ and ‘Introduction’.

- For an analysis of existing police guidance on police use of live facial recognition (LFR) technology, read ‘Biometrics since Bridges: Does the UK governance landscape for biometrics comprise a ‘sufficient legal framework’?’. This section determines whether this guidance meets minimum legal standards, and presents evidence that existing guidance and standards for biometrics governance are not fit for purpose.

- To understand our recommendations for a new legislatively-backed legal framework, read ‘The case for comprehensive biometrics regulation’ and ‘Conclusion’, including our full list of policy recommendations.

If you are a researcher, advocate or journalist:

- For a brief overview of the report, read the ‘Executive summary’ and ‘Introduction’.

- For an understanding of how biometric technologies are being deployed across the UK, read ‘How are biometrics being used in the UK?’.

- For a legal analysis of current governance, read ‘Biometrics since Bridges: Does the UK governance landscape for biometrics comprise a ‘sufficient legal framework’?’. This section analyses two pieces of prominent police guidance on use of live facial recognition (LFR) technology against the legal standards set out in the Bridges vs. South Wales Police judgment, concluding it does not fully meet established legal standards. Read ‘Annex 1’ and ‘Annex 2’ for further information.

- To understand our recommendations for a new legislatively-backed legal framework, read ‘The case for comprehensive biometrics regulation’ and ‘Conclusion’, including our full list of policy recommendations.

If you are new to biometrics governance or interested in learning what it is:

- Read the ‘Introduction’, the ‘What are biometrics?’ section and the ‘How are biometric technologies being governed in the UK?’ section for an understanding of biometric technologies and to know more about the current landscape of biometrics governance in the UK.

Executive summary

Biometric technologies are a powerful set of tools for measuring and inferring characteristics about people. These technologies come with an accordingly consequential set of risks to individuals, deployers and society more broadly. The most prominent application of biometrics has long been facial recognition technology in surveillance contexts. In 2020, the UK courts passed Bridges, the only judgment to date on the conditions for lawfulness of its use, and which can be boiled down to whether we have a ‘sufficient legal framework’ in place. In 2022, the Ada Lovelace Institute (Ada) published Countermeasures, a synthesis of legal analysis and public engagement research which recommended a comprehensive legal framework that would enable the safe, lawful use of biometrics.

In the following years, the deployment of these applications has grown, by police, across public transport networks and in the private sector. A new generation of equally invasive inferential biometrics has hit the market. This new generation of technologies claims to infer a person’s emotions, intentions, attention, truthfulness and other internal human states. The ability to appropriately manage the risks of these technologies has not matured alongside this growing appetite for use.

On the brink of mass rollouts of biometric technologies, this report considers the UK’s current approach to biometrics governance. We specifically consider the governance of police use of live facial recognition (LFR) technology – one of the most prominent and widespread applications of biometrics in the UK – and the sufficiency of its governance, as an indicator of how effectively biometrics are governed overall.

While LFR governance is notionally the most advanced across all biometrics, it is characterised by a ‘diffused approach’ which supplements existing laws with a patchwork of guidance and standards. We provide an overview of how biometrics are being deployed in the UK across law enforcement, private sector surveillance and biometric inferencing; consider existing governance mechanisms including regulatory guidance, policing guidance, local policies and practice standards; and evaluate whether these measures incorporate adequate safeguards for safe deployment.

This report identifies significant gaps and fragmentation across biometrics governance, the depth of which urgently necessitates the introduction of an alternative approach. It recommends adopting a centralised model, consisting of a comprehensive legal framework that provides clarity on the limits, lawfulness and proportionality of biometric systems, including newer inferential biometrics.

The highly fragmented nature of biometrics governance makes it very difficult to know if police use of LFR is lawful; whether there is in fact a ‘sufficient legal framework’ in place remains unclear. This results in some police forces pushing ahead with risky deployments while others are discouraged from making use of new technologies. This legal uncertainty nevertheless represents the high-water mark of biometrics governance in the UK; it is the application with the best – if still deficient – legal framework. Crucially, all other biometric technologies and deployment types, such as retrospective facial recognition (RFR) or ‘emotion detection’, have much less developed regulatory oversight and guidance, and consequently stand on much shakier legal ground, despite their active use.

Policymakers interested in both mitigating the harms of these powerful technologies and ensuring the safe realisation of their benefits are invited to consider the recommendations below.

Key recommendations

The UK government should develop a comprehensive, legislatively backed biometrics governance framework that gives effect to the recommendations below. The framework should:

- Be risk-based and proportionate, with tiered legal obligations depending on the risk level of the biometric system – analogous to the categorisation of different biometric systems in the EU AI Act.

- Specify safeguards in law for biometric technologies that build on those provided in existing regulation such as data protection law. Different measures would only apply to biometric applications posing a relevant level of risk, ensuring proportionality of compliance requirements.

- Adopt the definition of biometrics as ‘data relating to the physical, physiological or behavioural characteristics of a natural person’ to ensure newer applications like inferential biometrics are addressed. It should also allow for new categories of biometric data and system definitions to be added and removed over time, for example, through secondary legislation.

- Establish an independent regulatory body to oversee and enforce this governance framework.

- Grant the independent regulatory body with powers to develop binding codes of practice specific to use cases (e.g. a code of practice on inferential biometrics, or biometric applications of forthcoming 6G sensing technologies).

- Task the independent regulatory body, in collaboration with policing bodies, to co-develop a code of practice that outlines deployment criteria for police use of facial recognition technologies, including live, operator-initiated and retrospective use.

Methodology and evidence base

Where not otherwise cited, the evidence in this report was derived from desk research carried out by the authors, and a legal analysis of the safeguards set out in the R Bridges vs Chief Constable of the South Wales Police judgment, and whether they are addressed by two prominent pieces of police guidance on the use of live facial recognition: The College of Policing Live Facial Recognition Guidance,[1] and the Metropolitan Police Service (MPS) Overt LFR Policy Document.[2]

For the legal analysis, see Annexes 1, 2 and 3 at the end of this report.

Introduction

The deployment of biometric technologies, like facial recognition, is becoming increasingly prevalent across the UK. In the last year, facial recognition systems have been deployed by Network Rail to detect passengers’ emotions;[3] in local schools to facilitate cashless payments;[4] by mass retail chains to identify shoplifters;[5] and across police forces to flag individuals on police watchlists.[6] [7] [8] Significant investment in, and pilots of, biometric applications in publicly accessible spaces also suggest that biometrics will continue to be deployed at scale over the next few years.[9] [10] [11]

Public authorities maintain that these technologies can help to reduce crime, prevent terrorism and protect vulnerable people.[12] However, there is also consensus[13] that these systems pose risks to legal and human rights, including the right to privacy, as set out in the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). Ada Lovelace Institute (Ada) has previously advocated for dedicated biometrics legislation in the UK (see our report Countermeasures[14]) and on the brink of mass rollouts of these systems, there is a need to urgently revisit and review the adequacy of the UK’s biometrics governance landscape to identify if and where additional measures may be needed to ensure the safe and lawful deployment of these technologies.

The current biometrics governance landscape has been shaped by legal precedent. In 2020, for the first time globally, the UK’s Court of Appeal considered the legality of biometric technologies – with specific consideration to police use of live facial recognition (LFR) technology. In this case, R Bridges vs Chief Constable of the South Wales Police, the claimant Edward Bridges challenged South Wales Police’s (SWP) use of LFR technology in public spaces.[15] The SWP had deployed facial recognition technology via a live feed from CCTV cameras to match facial images and biometrics with watchlists compiled from existing custody photographs. However, Bridges argued that the SWP was breaching data protection laws, equality laws and the individual’s fundamental right to privacy.[16] On 11 August 2020, the Court of Appeal ruled that the SWP’s specific use of LFR within this context was unlawful and breached fundamental rights. The court also set out a series of mandatory standards and practices that subsequent police use of LFR must meet in order to be safely and lawfully deployed (see Annex 1 for a summary of these standards).

This was a groundbreaking ruling for the governance of biometric technologies for two reasons. First, it was the first time a court of such stature considered the legality of biometric technologies, setting out unambiguous legal and practical standards for police use of live facial recognition. While the ruling specifically considered the sufficiency of the UK laws for police use of LFR, this has served as a critical benchmark for the legality of other biometric systems that pose equivalent or higher levels of risks and must be held to at least the same legal standards; a ‘sufficient legal framework’. Second, the judgment made clear that the laws governing biometrics in the UK have ‘fundamental deficiencies’ with respect to upholding the public’s rights, including the right to privacy enshrined in the European Convention on Human Rights.[17]

While the Bridges judgment identified mandatory practices needed for LFR to occur under a sufficient legal framework, it was not prescriptive about what structure that should take.

There are broadly two governance models that could theoretically satisfy these requirements:

- Diffused governance model: This is the UK’s current approach to biometrics governance, which supplements existing laws with a patchwork of guidance and standards that aim to incorporate the mandatory practices and legal requirements set out in the Bridges These documents are developed and owned by a diffuse set of actors, including regulators, policing bodies and central government. Policymakers and police forces have criticised this model as both insufficient and inhibitory of legitimate deployment (see Box 1 below).

- Centralised governance model: This alternative model consolidates mandatory practices and legal requirements into dedicated biometrics legislation and designates a centralised regulatory body to act as the single source of oversight, clarity and enforcement.

Box 1: Consensus on centralised model for biometrics governance

Support for a more holistic model for biometrics governance is widespread among policymakers. The former Biometrics and Surveillance Camera Commissioner (BSCC) Fraser Sampson published his annual report in 2022–2023,[18] shortly before leaving the position, which emphasised the need for ‘proper regulation’ of biometric systems in the UK. He warned:

‘There is a risk that legislation and oversight of growing technology will fall further behind. This apparent lack of interest in proper regulation is borne out by the reluctance […] to address the need for further regulation in the Live Facial Recognition space […] Strong, legally enforceable regulations bring clarity and certainty to how rapidly growing technologies could be used in accordance with the law.’

In January 2024, the UK’s Justice and Home Affairs Committee published a letter to the Home Secretary, James Cleverly MP, raising concerns about the use of live facial recognition (LFR) technology by police forces in England and Wales.[19] The letter identifies key issues including the absence of a legal foundation for LFR deployment, lack of clear standards and regulation and inconsistent training across police forces, and recommends developing a comprehensive legal framework:

‘We do not consider the current methods of oversight sufficient […] We believe that, as well as a clear, and clearly understood, legal foundation, there should be a legislative framework, authorised by Parliament for the regulation of the deployment of LFR technology.’

In a parliamentary debate on police use of LFR in November 2024, the UK’s Minister of State for Policing, Crime and Fire Prevention, Dame Diana Johnson also cited concerns from police leaders that the lack of clear standards and regulation is a barrier for police deployment of these technologies.[20] She stated:

‘I have spoken to senior police leaders about the matter, and some believe that the lack of a specific legal framework inhibits their use of the technology and dampens willingness to innovate.’

This report considers the biometrics landscape since Bridges and evaluates whether the UK’s current approach to governance is adequate in practice, or whether comprehensive legal framework backed by legislation (centralised model) is needed to address the full range of both current and emerging risks posed by biometric systems.

What are biometrics?

Biometric data (shortened to ‘biometrics’) is personal data, often taken from or relating to a person’s body (biological biometrics) or behaviour (behavioural biometrics), that can be used to uniquely identify or categorise them. Biological biometrics include fingerprints, iris scans, voice recognition and facial recognition, while behavioural biometrics include traits like gait analysis or keystroke analysis.[21]

Biometric technologies use biometric data to derive information about people; for example, to verify, identify or categorise people based on characteristics such as their gender, age, race or mood.[22] These functions are described in more detail below.

Biometric verification systems confirm or validate the identity of a particular person (also referred to as ‘authentication’). These systems check that the individual’s biometric data matches a profile that already exists on a device or in a database. Examples include digital identity authentication services (e.g. Yoti,[23] Onfido[24] and Credas[25]) and device authentication features (i.e. face and fingerprint recognition to unlock devices).[26]

Biometric identification systems determine the identity of an unknown person. These systems compare biometric data of the person being identified against a database of biometric profiles, with the aim of finding a match. Examples include retrospective or live facial recognition systems used to identify an individual from a watchlist of people suspected or convicted of a crime.[27]

Biometric categorisation systems are used for classification and inference. They often involve pseudo-scientific assumptions to draw links between external features and other traits.[28] There are two types of systems:

- Biometric classification involves analysing an individual’s biometrics to deduce characteristics about them and assign them to a specific category, such as age, gender, ethnicity or likelihood of developing health conditions. Examples include age estimation systems used to determine an individual’s age when buying age restricted products (e.g. alcohol or tobacco).[29]

- Biometric inferencing involves analysing an individual’s biometrics to deduce their state, for example, emotion or intent. Examples include ‘emotion recognition’ systems, which have been deployed in contexts like hiring and education, despite concerns around both. [30] [31]

Different kinds of biometric applications pose substantially different risks, and these risks will depend on the specific use case in which the systems are deployed. A comprehensive biometrics governance framework will need to respond to the risks and harms posed by a range of biometric applications spanning identification, verification and categorisation functions, as well as by emerging biometric applications that fall outside of this taxonomy.

How are biometric technologies being used in the UK?

This section of the report outlines the wide range of use cases in which biometric technologies are already being deployed across the UK, by police and public bodies, in retail and commercial spaces, and for biometric inferencing.

Understanding prevalent use cases and their attendant risks is essential for determining whether harms are adequately addressed by the current patchwork of guidance and standards, or if a centralised approach is needed. In short, in the UK:

- Existing deployment types are growing, e.g. live facial recognition use by police and shops are scaling up and shifting to permanent installations rather than temporary deployments.

- Biometrics are being deployed in new public and digital spaces, e.g. at public transport stations for situational awareness and advertising, and in workplaces to clock people in and out.

- Deployers are trialling new types of biometrics at scale, e.g. police trialling facial recognition on bodycams, smartphones or retrospectively on CCTV.

- There is growing public access to digitally provided facial recognition services, e.g. PimEyes,[32] with evidence of informal use by public bodies such as the police.

- A new generation of biometrics that claim to infer sensitive internal human states like emotions, attention, intention or truthfulness are hitting the mainstream market.

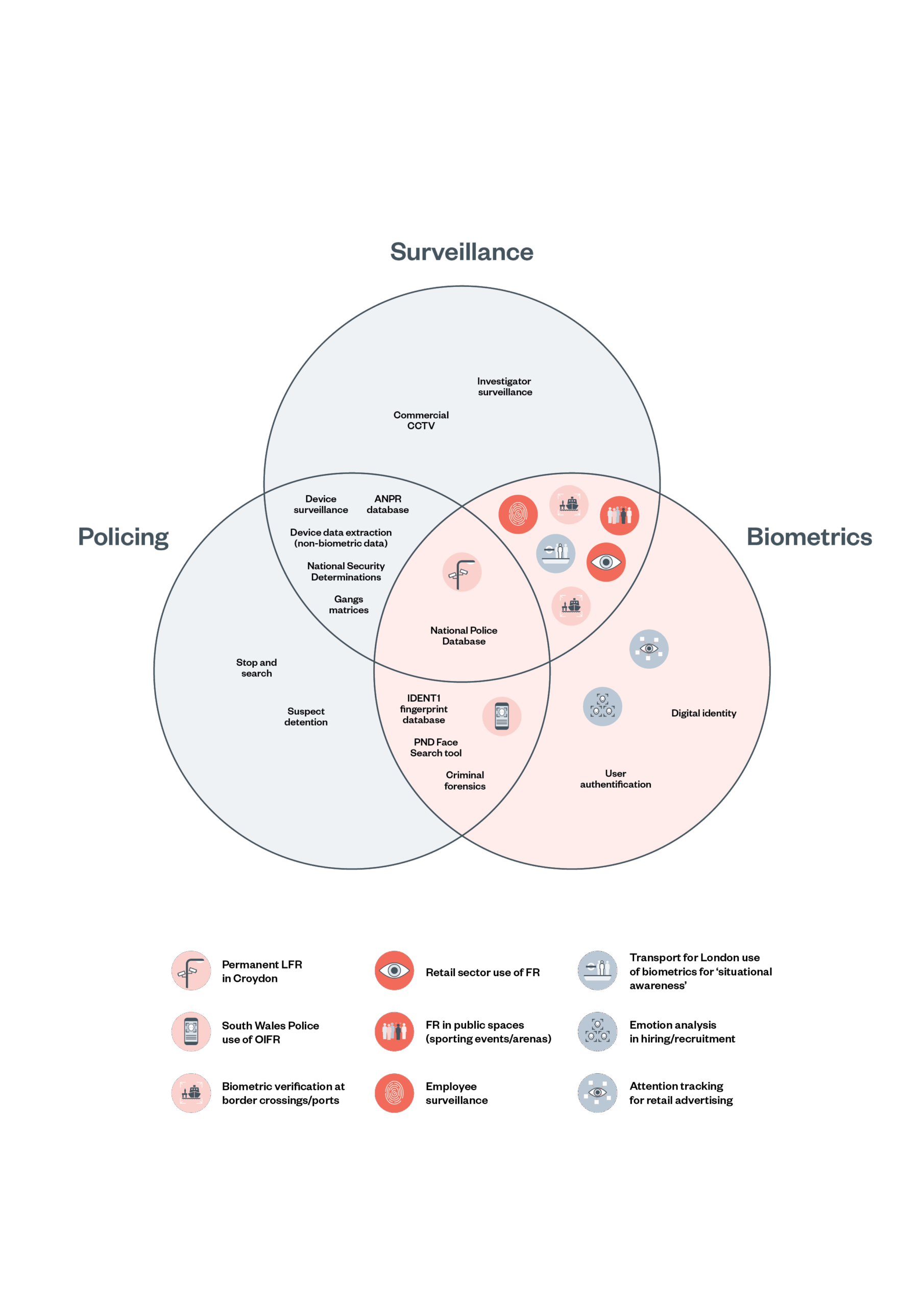

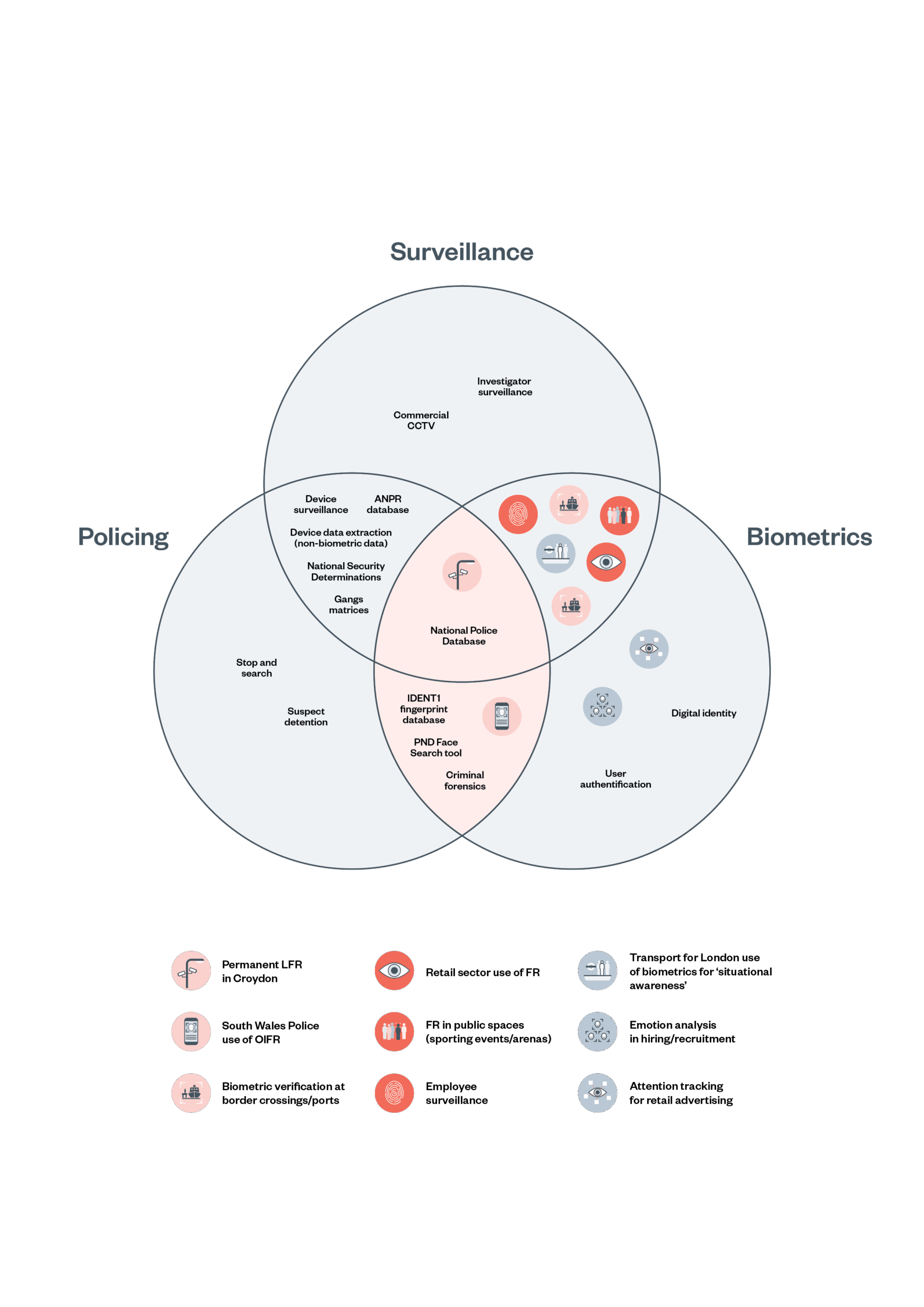

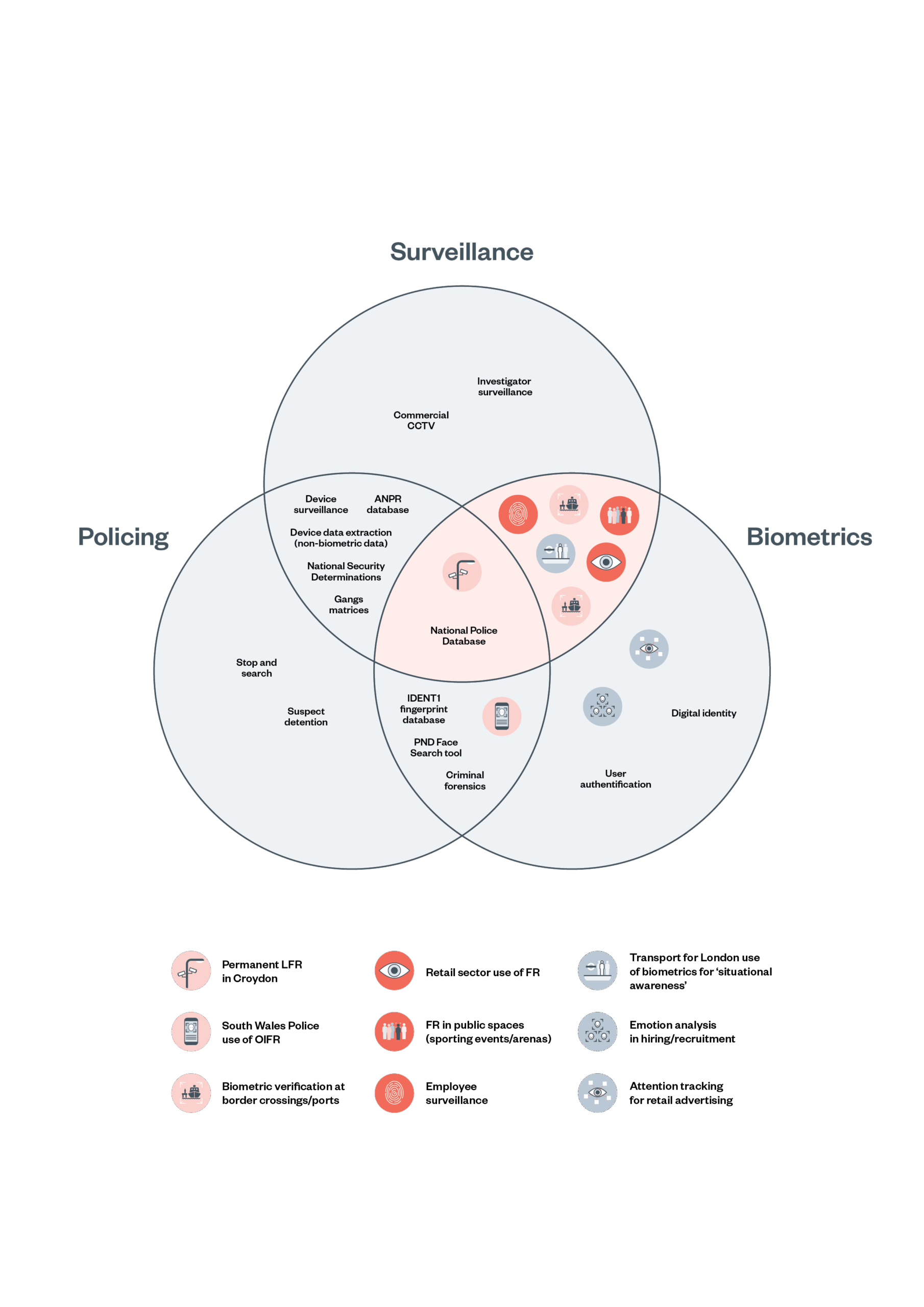

Figure 1: Current uses of biometrics in the UK

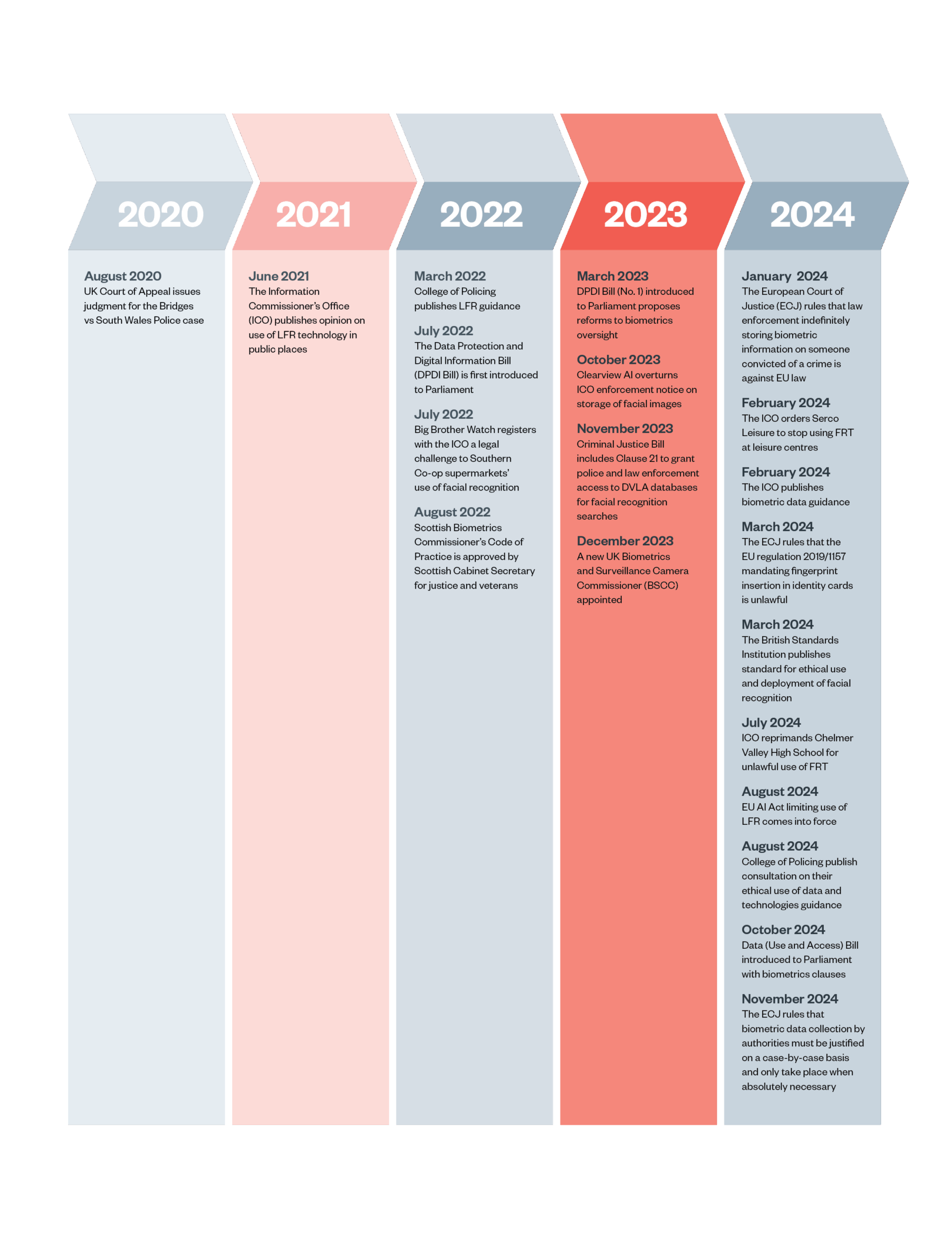

Figure 2: Timeline of biometrics governance developments in the UK

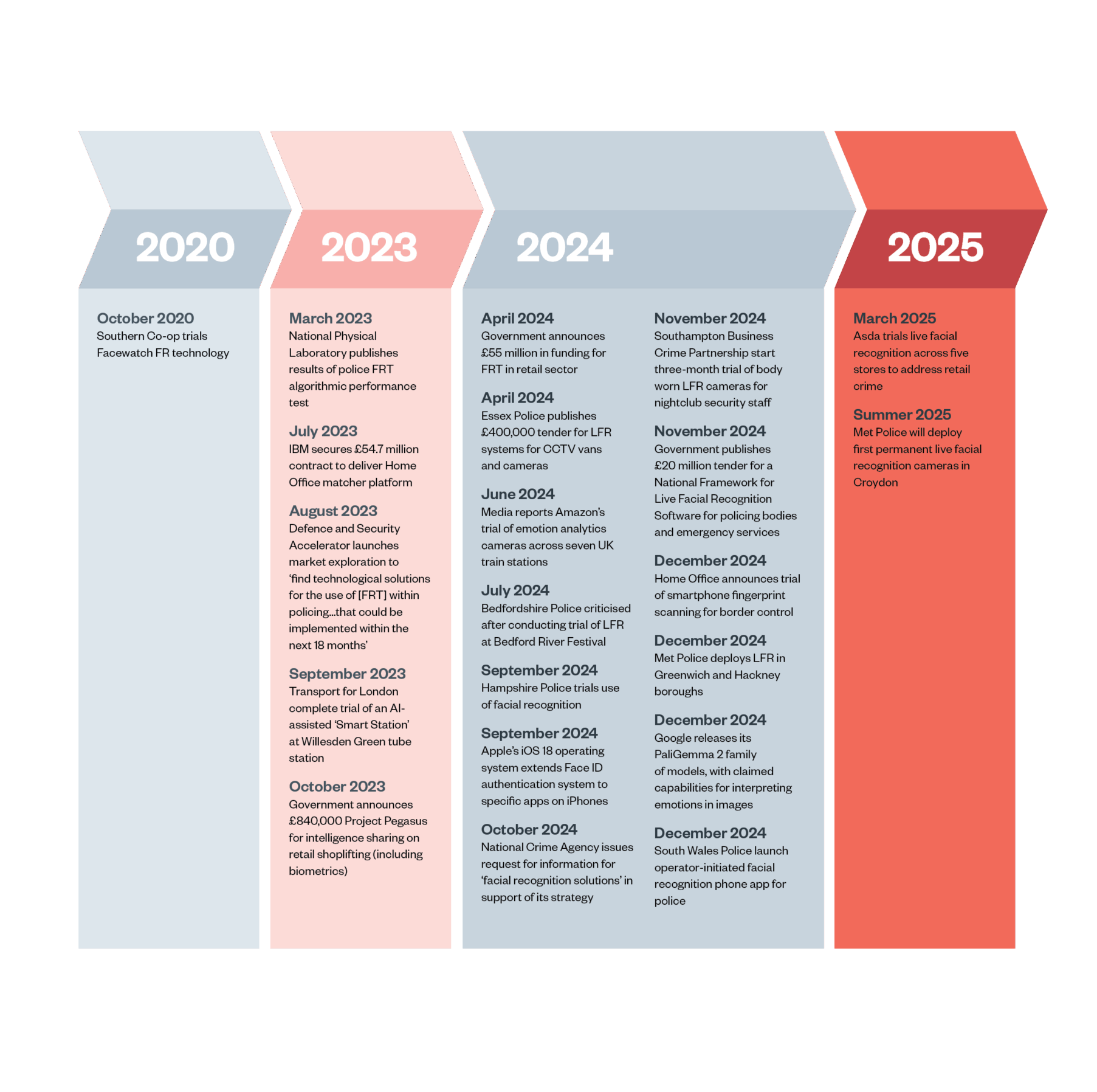

Figure 3: Timeline of biometrics deployment developments in the UK

Police deployment of biometric surveillance technologies

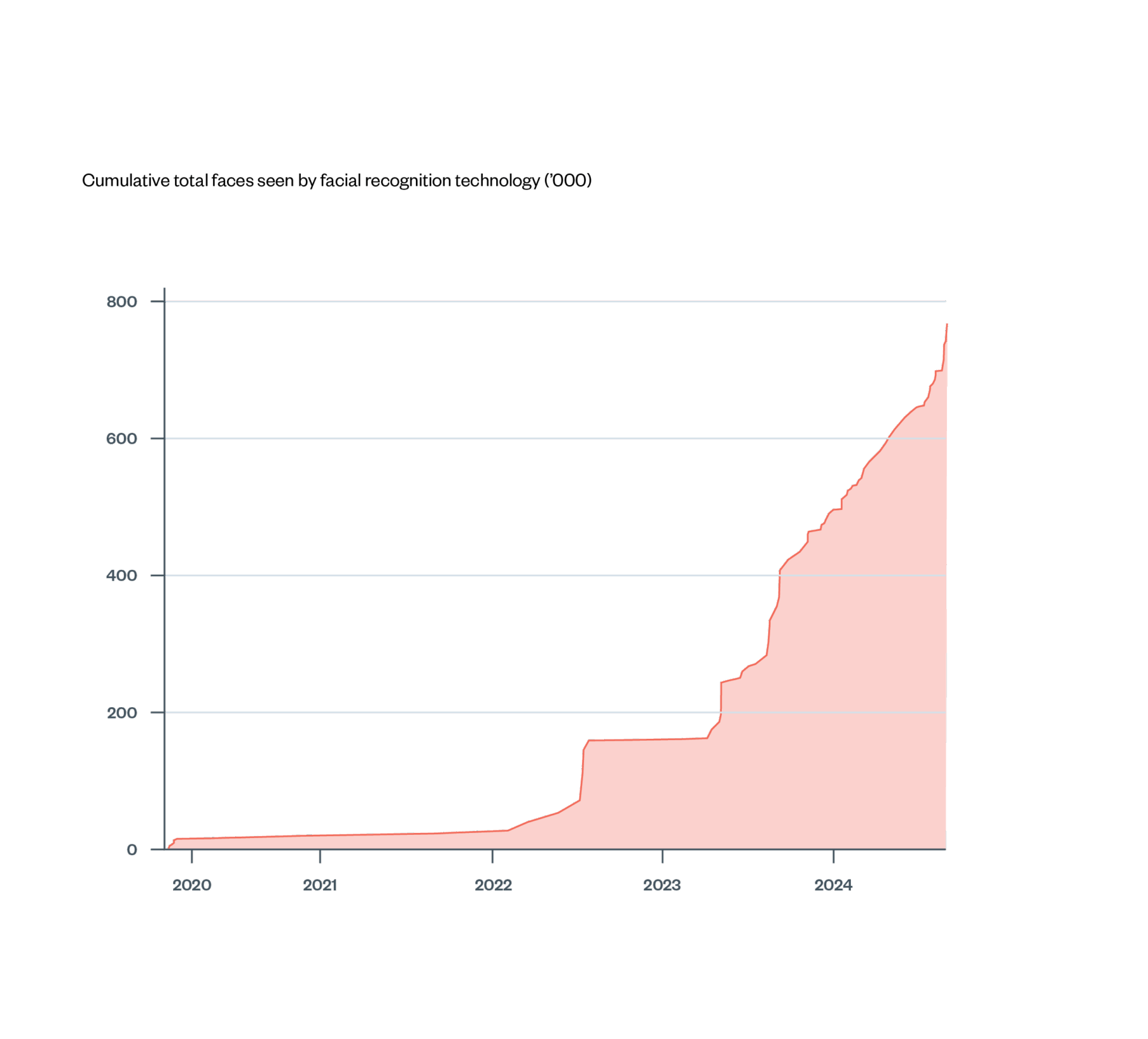

While the Bridges judgment highlighted several legal risks associated with police use of live facial recognition (LFR), this does not seem to have deterred police deployment of biometrics – specifically biometric mass surveillance technologies including facial recognition (see Box 2 below for more on these technologies). Since Bridges, police deployment of LFR has continued to scale significantly, as illustrated by Figure 4, which charts a dramatic rise in the volume of facial data processed by the Metropolitan Police over the last five years.

Figure 4: Total number of faces processed by the Metropolitan Police’s facial recognition technology[33]

Box 2: What are biometric mass surveillance technologies?

Mass surveillance refers to watching the public indiscriminately. This means monitoring the public despite a lack of reasonable suspicion, in a way that does not give people opportunities to provide genuine consent, or clear routes to opt in or out of being subject to the use of these systems.

Biometric mass surveillance technologies process biometric data in publicly accessible spaces (e.g. parks, squares, arenas and train stations), for the purpose of performing mass surveillance. These technologies pose unique risks to fundamental human rights, because performing untargeted biometric recognition in public spaces relies on the indiscriminate collection, processing and/or storage of sensitive biometric data. Moreover, this data collection is undertaken on a large scale, and often without the control or knowledge of passersby, whose presence is intrinsic to public spaces. As a result, biometric mass surveillance technologies create a perception of being constantly surveilled, which can create a ‘chilling effect’, as well as restricting fundamental rights and freedoms and disincentivising people from participating in public life.[34]

As indicated in the chart above, police forces across the UK continue to deploy biometric mass surveillance technologies at scale. In London, the Metropolitan Police recently announced the installation of the city’s first permanent LFR cameras, which will be mounted on street furniture (e.g. streetlights and lampposts) in Croydon in summer 2025.[35]

Over the last few years, local police forces across the UK have also trialled LFR systems at a number of public events. In July 2023, the Northamptonshire Police started using LFR at the British Grand Prix in Silverstone, scanning over 370,000 faces without triggering any matches or alerts.[36] In October 2023, the Essex Police first trialled LFR, and subsequently published a £400,000 tender for the integration of LFR systems into CCTV vans and cameras.[37] And in July 2024, Bedfordshire Police trialled LFR at the Bedford River Festival in July 2024, quickly followed by Hampshire Constabulary in September 2024.[38],[39]

Beyond LFR, police forces have experimented with the deployment of other kinds of facial recognition. In December 2024, the South Wales Police became the first force to launch an operator-initiated facial recognition (OIFR) mobile phone app, enabling police to confirm the identity of an unknown person at the touch of a button. The app compares a photograph of a person’s face, taken on a police issue mobile phone, to an image reference database, to help the officer identify a person in real time.[40] Meanwhile, the Metropolitan Police has deployed retrospective facial recognition (RFR) where any historical footage can be compared against a watchlist or database to identify an individual.[41] In addition, in June 2024 Police Scotland announced a £13.3 million national contract for body worn cameras (from which the images could be used for retrospective identification) but have delayed their deployment until 2025.[42]

The widespread deployment of different kinds of facial recognition technologies across police forces may be, in part, emboldened by research studies reporting considerable improvements in the accuracy of these systems. We consider the Facial Recognition Technology Study in Law Enforcement Equitability Study by the National Physical Laboratory (NPL) in Box 3 below:

Box 3: Does the National Physical Laboratory study mean it is safe to use? Findings and limitations from police facial recognition testing

In short, the National Physical Laboratory (NPL) study does not confirm LFR is generally safe to use. It represents a snapshot of the performance of a single software version in idealised conditions and precise settings – much like certifying that a single version of a smartphone’s operating system is bug-free. It does not require police to validate every subsequent version of LFR technologies, or use it under those settings or conditions.

In March 2023, the NPL published its Facial Recognition Technology in Law Enforcement Equitability Study,[43] the results of which have emboldened many police forces to deploy facial recognition technologies. This study assessed the performance of ‘NEC Neoface V4 1’ and ‘HD5 Face Detector’, algorithms used by the Metropolitan Police and South Wales Police forces for live facial recognition (LFR), retrospective facial recognition (RFR) and operator-initiated facial recognition (OIFR), and placed particular focus on their performance across protected characteristics such as race, age and sex.

Under specific and controlled testing conditions, both RFR and OIFR had a 100 per cent true-positive identification rate (TPIR) – they reliably recognised every individual on a designated watchlist that passed through the recognition zone. In comparison, the LFR system demonstrated a lower TPIR of 89 per cent when testing for accuracy against both 1,000- and 10,000-people watchlists, meaning 89 out of 100 subjects were identified by the technology.

Importantly, the false-positive identification rate (FPIR) – which measures how often the system incorrectly flags someone not on the watchlist – was influenced by the size of the watchlist. For LFR, the average FPIR for the 1,000-person watchlist was one in 60,000 while the rate increased to one in 6,000 for the 10,000-person watchlist. As watchlist size increases, the likelihood of false alerts also rises. A system deployed in a busy city centre might expect to process 100,000s of people, making it likely each deployment causes some false positives and potentially wrongful interventions at this accuracy level.

Crucially, demographic variation in the FPIR depended on the threshold settings of the algorithms. A ’face-match threshold’ defines a numerical value, often a minimum percentage or score, that is required for the system to identify images as matching. This score reflects how closely a new image resembles one already in a database. The threshold can be adjusted within the facial recognition system and allows users to tweak the system based on a desired degree of accuracy.[44] The NPL study reported a statistically significant higher rate of false positives observed for Black people under certain threshold settings. A threshold of 0.6 needed to be used to ensure equitability. This means if operators lower thresholds – to increase the likelihood of identifying individuals, or through ignorance or error – this creates tangible risks of discrimination.

In addition, the report evaluated these biometric systems in near-ideal conditions, at a single point in time, and concluded that if facial recognition systems are deployed in accordance with specific settings and in similar conditions, then they can be expected to achieve high levels of performance.

However, the report does not represent an ongoing duty for iterative testing and evaluation, or to analyse new versions of the software for safety over time. The report also lacks the power to prescribe specific requirements for police use. Without requirements, deployment settings can be determined at the discretion of individual police officers, which can result in uninformed, biased or inconsistent applications of the technology. Instead, a regulator is needed to set out the specific conditions for where, when and how these facial recognition systems can be safely deployed by police.

The report also points to several areas for further investigation based on gaps in the study. For example, the study did not account for the effects of ‘template ageing’, which occurs as people’s facial features change over time. This can lead to discrepancies between an individual’s current appearance and the facial features stored in the ‘template’ image within the reference watchlist database. To maintain accuracy, facial recognition templates may need to be updated regularly to reflect these changes in an individual’s appearance.

The study also did not explore the effects of lower quality videos and images (i.e. due to file compression) on LFR performance, which is particularly relevant for mobile phone applications, including OIFR apps. The study noted that for trials ‘when a facial image taken was considered unsatisfactory by the photographer (e.g. out of focus, motion blur, subject eyes shut), generally a second image would be taken’. This demonstrates the importance of, and reliance on police operator competency in using these technologies. It remains to be seen how on-device facial recognition will work in practice.

Beyond the boundaries of this study, some have noted that the perceptions of technology as infallible (for example, over-generalising results such as the 100 per cent TPIR for RFR and OIFR in this study) may have unintended consequences. This includes overreliance on the technology at the expense of other evidence or creating the false impression that there is a minimal need for guidance and operator discretion.[45]

In addition to the law enforcement use cases detailed above, there are several initiatives to pilot and scale biometric technologies across the public sector. Recent government tenders have been published to develop a ‘biometrics solution for passenger enrolment’ at Manchester Airport,[46] as well as a Scottish Government identity verification service.[47] In October 2024, the Home Office also published a £195 million contract notice for a partner to manage and develop various border control technology systems. This includes the Border Crossing (‘BX’) system for searching passenger records using biometrics and an associated ‘Helios’ watchlist database.[48] Two months later, a privacy information notice published by the Home Office detailed plans to trial remote and in-person fingerprint collection using smartphones, with a view to speeding up visa application processes for foreign nationals.[49] Most recently, biometric technologies have been piloted in UK maritime ports to identify passengers in their vehicles, ‘enhancing security and border control efficiency’.[50]

The breadth of scale of these deployments across police and public sector bodies demonstrates a significant investment in and expansion of the geographic and temporal reach of facial recognition-based surveillance across the UK. As the technology continues to be deployed at scale, it is essential to verify that these applications meet the legal standards set out in the Bridges judgment to ensure that they do not jeopardise or breach fundamental legal and human rights.

This report will set out the UK’s current biometrics governance framework (referred to as the ‘diffused governance model’) and consider whether it encompasses adequate safeguards for the lawful deployment of the biometric applications set out in this section (i.e. facial recognition deployed by police and UK public bodies) or whether a more comprehensive, and centralised approach is needed.

Private sector deployment of biometric surveillance technologies

The deployment of biometric surveillance by commercial actors – in particular shops and entertainment venues – has developed on a similarly rapid trajectory to law enforcement. This has been simultaneously driven and entrenched by a blurring of the boundaries between public and private policing functions – as evidenced by the Labour government’s September 2024 Terrorism (Protection of Premises) Bill, which seeks to place legal obligations on certain event organisers and venue owners to monitor premises and reduce risks of terrorist attacks.[51]

The use of facial recognition in retail stores is a particularly common use case, for the purpose of reducing shoplifting offences. In March 2025, Asda began a two-month trial of LFR across five locations in Greater Manchester.[52] Similarly in October 2020, the Southern Co-op trialled the RFR technology Facewatch across 35 of their convenience store locations.[53] Since then, Privacy International has reported other retailers including Home Bargains, Morrisons, Flannels and Sports Direct are using LFR software supplied by the company.[54] Facewatch claims that retail LFR can reduce shoplifting offences by ‘at least 35 per cent in the first year’.[55] Seemingly influenced by these economic arguments, in October 2023 the Association of Police and Crime Commissioners established the Pegasus partnership between police and businesses. The initiative provided over £600,000 of funding along with intelligence sharing to ‘build a comprehensive intelligence picture of the organised crime gangs that fuel many shoplifting incidents’,[56] with facial recognition playing a central role.

Biometric systems are also increasingly used to fulfil a number of private security functions, for example in nightclubs and at sporting events. In November 2023, the Southampton Business Crime Partnership commenced a three-month trial of body worn LFR cameras for security across seven venues in the city.[57] A market intelligence agency survey of global venues for sporting events also found that half of the venues reported biometrics as a top ‘innovation priority’ for 2025,[58] with uses spanning identity verification, payment automation and security surveillance.

Private sector use of biometrics has also given rise to the use of biometric surveillance technologies in the workplace, such as for employee monitoring. In 2024, the UK company Serco Leisure deployed facial recognition and fingerprint scanning to monitor more than 2,000 employees across 38 leisure facilities, for the purpose of attendance tracking and subsequent payment for their time. In February 2024, the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) issued an enforcement notice against the company for unlawful deployment of the systems, which were deemed not necessary or proportionate for this purpose.[59]

These examples show that biometric surveillance technologies continue to be deployed at scale – not only by police and public sector bodies, but also increasingly in commercial, retail and publicly accessible spaces. Private sector biometric surveillance technologies not only pose equivalent risks to the public as police use of LFR, but these risks are exacerbated by the fact that private sector organisations have weaker guidance and standards than police, making it less likely that the fundamental deficiencies in UK legal safeguards have been addressed in this context.

Theoretically, private sector actors using biometrics for identification without consent must show they create ‘substantial public interest’ in doing so, but outside of the ICO’s Facewatch investigation, it is unclear whether the range of companies deploying LFR in retail setting meet this test. Companies are also not covered by other laws relating to freedom of information, investigatory powers, procurement and parliamentary reporting that hold public bodies to account.

While the Bridges judgment sets out mandatory legal requirements for police use of LFR, a comprehensive legal framework for biometrics must ensure that other systems of equivalent or higher risk, such as private sector surveillance, are held to at least the same standards. In the section of this report ‘The case for comprehensive biometrics regulation: Outlining the risks of partial approaches’, we consider how a centralised governance framework can address the diverse harms posed by a range of high-risk systems.

Biometric inferencing

Beyond the increased prevalence of biometric surveillance technologies to perform both public and private policing functions, there has also been a considerable rise in the deployment of inferential biometrics – technologies that seek to categorise people and infer sensitive internal states. While inferential biometrics and emotional analytics are not novel technologies – these systems have roots in psychographic technologies such as lie detectors, which have been used for decades – rapid advancements in AI have led to a step-change in the capabilities of these systems, which are now seeking to predict people’s long-term physical, physiological or behavioural characteristics,[60] and used for situational awareness, emotion analysis and attention tracking.

Before delving into how these technologies are being deployed, it should be noted that these systems can be deeply problematic:

- Scientific consensus does not support the idea that complex emotional or psychological states can be reliably inferred from physical traits, especially across diverse populations.

- Such systems tend to reinforce harmful stereotypes, such as misinterpreting neurodivergent behaviours, cultural expressions or disability-related traits as signs of disengagement, dishonesty or aggression.

- These systems often operate without transparency or recourse, meaning individuals have no meaningful way to know how decisions are made or to challenge inaccurate assessments.

Despite these risks, inferential biometrics are being piloted across a number of high-risk use cases, including transport, recruitment and education. These use cases are outlined in more detail below.

Transport

In September 2023, Transport for London (TfL) trialled an AI-assisted Smart Station at Willesden Green underground station, to provide real-time insights on passenger behaviour.[61] While facial recognition was not used in the pilot, it did scope technical requirements for a ‘fare evasion scenario’, where facial images of repeat offenders would be unblurred to facilitate identification.

Further trials are reportedly taking place across the network, with the purpose of improving passenger safety and staff ‘situational awareness’.[62] In June 2024, it was also reported that Network Rail trialled an even more invasive biometrics application, trialling Amazon’s emotional analytics system in eight UK rail stations. The system analysed footage from CCTV cameras, interpreting facial expressions and non-verbal cues for ’situational awareness’, namely to identify ‘distressed passengers’, potentially allowing officers to pre-empt conflicts or emergencies.[63]

Recruitment and employment

Biometric inferencing has also been used for emotion analysis in high-risk contexts like recruitment and employment. In January 2021, there was public outcry around HireVue’s facial analysis software and its integration into video interview tools that claimed to assess a job candidate’s personality traits based on expressions and intonations. HireVue subsequently removed the facial analysis component from its tooling.[64]

The ICO has since warned companies to exercise caution when using emotional analytics systems, due to the ‘pseudoscientific nature’ of theories underpinning these technologies.[65] Researchers have also cautioned about the limitations of legal frameworks for ‘biometric psychography’. Data from haptic technologies, brain-computer interfaces and other biosensors (e.g. pupil dilation or heart rate) can reveal intimate details about the subject’s interests,[66] and it is unclear whether existing legal frameworks offer adequate protections.

Attention tracking

Biometric inference applications are also being developed for attention tracking – used to measure an individual’s attention and engagement with a particular stimulus. In 2022, responding to the increase in online learning, Intel piloted a student monitoring software called Class that measures student engagement by using emotion analysis to determine whether students are bored or paying attention, based on facial expressions.[67] Alternatively, other providers like EduLegit offer student monitoring software that uses gaze tracking to monitor student gaze patterns to ‘ensure integrity in assessment and exam scenarios’.[68]

Influencing consumer behaviour

It is also important to consider how inferential biometrics could be used to underpin emerging technologies and future business models. For example, researchers at the Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence have raised concerns about the nascent ‘intention economy’.[69] As they describe: ‘The near future could see AI assistants that forecast and influence our decision-making at an early stage, and sell these developing intentions in real time to companies that can meet the need.’ The implications of this include influencing people’s intentions around purchasing or voting. The paper details concerns around ‘automated persuasion’ and the increasingly detailed datasets extracted from users’ interactions with large language models (LLMs), and it is easy to envisage how biometric data could be extracted to infer emotional states and fuel these markets in the future.

Inferential biometrics used for situational awareness, emotion analysis and attention tracking are being deployed at scale, despite significant concerns about the ‘pseudoscientific nature’ of the theories underpinning these technologies. Namely, biometric inferencing systems that use biometric data, such as tone of voice or facial expression, to assess internal states or competencies (e.g. the use of emotion recognition to inform decisions around recruitment) are based on unproven underlying assumptions. The relevant psychology literature indicates that it is not possible to consistently infer internal emotional states from external facial expressions. The deployment of these systems, particularly those used to make predictions, recommendations or decisions in high-risk use cases like recruitment and employment, poses significant risks to individuals.

Box 4: How does the law apply to ‘Emotional AI’?

Inferential biometric systems are being deployed across several real-world use cases, including across TfL and Network Rail networks to understand consumer behaviour and reportedly support advertising. Other use cases include to determine attention in schools and to judge job candidates in automated video interviews – though some companies have restricted emotional analytics from video interview software more recently, due to concerns about accuracy and discrimination. Crucially, these systems are not simply using biometrics for identification – to identify who a person is – but rather are being used to infer what these individuals are thinking, feeling or what kind of groups they might belong to. This has important legal implications.

Under the UK GDPR (2018), there is an important legal distinction between biometric data and special category biometric data. Special category biometric data – which is biometric data used specifically for the purpose of identification – receives stronger legal protections. While the use of any biometric data is subject to GDPR, the highest level of protections only applies to biometric identification applications. This creates a significant gap in the law.

The UK GDPR was designed to provide the highest protections to the most privacy-affecting use cases of biometrics – i.e. identification. As a result, it does not extend these higher protections to newer and arguably more sensitive uses of biometric systems, such as those inferring emotions, mental states or characteristics. As biometric inferencing and emotional analytics systems continue to be deployed, this gap leaves individuals vulnerable to intrusive uses of their data.

While the Bridges judgment sets out the legal standards that police must follow when using LFR, an equally robust legal framework is needed to cover other types of high-risk biometric technologies, including inferential biometrics. In the next section, we examine how a centralised model could address the risks posed by these technologies.

How are biometric technologies being governed in the UK?

In light of the biometrics deployments covered in the previous section of this report, it is essential to examine the UK’s evolving biometrics governance and legal landscape, to determine whether the current approach to governance (i.e. the diffused model) incorporates appropriate safeguards for this wide range of use cases, or whether a centralised approach to governance is needed. To summarise, in the UK:

- The biometrics governance landscape is fragmented. Multiple regulators oversee biometrics, which can lead to confusion and lack of accountability.

- Recent legislation, including the Investigatory Powers (Amendment) Act and the anticipated Crime and Policing Bill, suggests expanding access to and use of biometrics, especially for law enforcement, with comparatively little focus given to strengthening safeguards for these applications.

- The UK relies heavily on soft-law instruments like guidance, ethical principles and technical standards. However, there is a patchwork of guidance and standards, and this diffused approach lacks statutory enforceability.

- There is a precedent for a centralised model. In contrast to the UK’s diffused approach, the EU AI Act has set out centralised, risk-based and statutory regulation for biometrics, including bans on high-risk biometric applications.

UK regulatory landscape

Responsibilities for governing aspects of biometric technologies are spread across a number of UK regulators.

The Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO)

The ICO is the UK’s data protection regulator, whose data protection responsibilities are set out in the Data Protection Act 2018 and the UK GDPR, including biometric data. Biometric data is considered personal data under this regime, although only biometric data used for the purpose of identification is considered ‘special category’ data and afforded greater protection (for example, with respect to whether and how it can be used without consent).

The ICO has done considerable work on the use of biometric technologies, including conducting horizon scanning and research with public focus groups, developing guidance and opinions, hosting biometrics developers in their regulatory sandbox, and taking enforcement actions against a range of biometric applications.

In June 2021, the Information Commissioner issued an opinion on the use of live facial recognition (LFR) in public spaces, covering surveillance uses and data protection considerations for watchlist development.[70] In October 2022, the ICO published its Biometrics: Foresight report, which identified the use of behavioural biometrics in commerce, consumer health biometrics, employee biometric tracking, and behavioural analysis of students as emergent applications of potential concern.[71] Off the back of this report, the office also publicly expressed concerns about high-risk emotional analytics applications.[72]

Most recently, in February 2024, the ICO issued guidance on ‘biometric recognition’ systems that use biometric data to uniquely identify individuals.[73] The guidance emphasised that the use of biometric recognition systems requires a lawful basis and an Article 9 condition for processing special category data. This does not address biometric classification and/or categorisation systems.

The ICO has also enforced a number of biometrics-related enforcement cases, across both the public and private sectors. In July 2024, the ICO issued a reprimand to Chelmer Valley High School for failing to complete a Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA) prior to introducing a canteen payment system using facial recognition technology.[74] Earlier that year, the regulator issued enforcement notices ordering Serco Leisure to stop using facial recognition and fingerprint scanning to monitor their workers’ attendance.[75] However, not all enforcement cases brought forward by the regulator have been successful. While the ICO initially fined Clearview AI £7.5 million for unlawfully harvesting UK citizens’ facial images from the internet for their face matching service, this decision was overturned on jurisdictional grounds by the Information Tribunal.[76]

The Biometrics and Surveillance Camera Commissioner (BSCC)

The BSCC has dual responsibilities: 1) reviewing the police retention and use of biometrics samples, and 2) encouraging compliance with the Home Secretary’s Surveillance Camera Code of Practice (under the Protection of Freedoms Act 2012).

The BSCC has been a vocal presence in biometrics debates. In February 2023, the regulator published research into the police use of overt surveillance cameras in public spaces. The report openly criticised police forces for not responding to its survey, using particular biometric systems despite known security concerns, and demonstrating a limited understanding of the capabilities of the technologies being deployed.[77]

The BSCC’s 2023–2024 annual report also offered a firm challenge to the UK government’s use of biometrics across national security and policing. On the issue of facial recognition in public spaces, the Commissioner observed that:

‘The widespread rollout illustrates the potential regulatory and policy deficiencies that exist in dealing with biometrics that are neither fingerprints nor DNA. The way forward in the absence of additional regulation remains unclear […] I believe it incumbent upon government to engage more fully with civil liberties groups on risks and benefits of facial recognition technology, including structures and frameworks for the accountability of its use in public spaces.’

The Biometrics and Surveillance Camera Commissioner also called for increased transparency, community engagement, and testing of novel applications.

The Scottish Biometrics Commissioner (SBC)

The SBC oversees Police Scotland’s use of biometric data. The SBC’s responsibilities are comparable to the BSCC, but with greater capacity to affect real-world deployment. It is required to prepare a Code of Practice on the acquisition, retention, use and destruction of biometric data for criminal justice and police purposes,[78] and has corresponding enforcement powers over Police Scotland.[79]

In July 2024, the SBC called on the ICO to investigate Police Scotland’s use of the Digital Evidence Sharing Capability following a disclosure by Microsoft that it could not guarantee the sovereignty of policing data (including biometrics) hosted in the Azure public cloud.[80]

In January 2024, the SBC Dr Brian Plastow also offered a firm challenge to proposed legal changes that sought to broaden police access to biometrics. Criticising what he perceived to be ‘democratic backsliding’, the Commissioner advocated for ‘an alternative direction for Scotland where independent checks and balances over biometrics and biometric-enabled surveillance are strengthened rather than weakened to enhance public confidence and trust’.[81] Three months later, the Commissioner called for a ‘strategic reset’ for the UK’s biometrics strategy, alongside ‘the development of a “national biometric interoperability framework” to which independent oversight safeguards are applied.’[82]

It should be noted that there are several other horizontal and sectoral regulators whose remits may intersect with biometric technologies and use cases. For example, the Equality and Human Rights Commission has a remit to intervene or comment where biometric applications risk having unequal impacts across protected characteristics such as age, sex or race.

UK legal and parliamentary landscape

Since R Bridges vs Chief Constable of the South Wales Police, several biometrics-related legal developments have occurred, and considerable parliamentary attention has been given to proposals for supporting biometrics use and stimulating the associated market.

On 25 April 2024, the Investigatory Powers (Amendment) Act 2024 became law, changing aspects of how investigations by law enforcement and security and intelligence agencies are governed. Relevant amendments under the Act include relaxing requirements for agencies to obtain a warrant to retain personal data, which some have speculated could apply to facial images uploaded to public social media channels.[83] [84]

It’s unclear if legislative proposals relating to data governance and wider policing made under the previous Conservative government will be carried forward. The former Criminal Justice Bill sought to grant some organisations access to the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA) facial image databases ‘for purposes and circumstances as are related to policing or law enforcement’[85] although these measures do not seem to have been replicated in the current Crime and Policing Bill.

Biometrics-related provisions have also been included in the government’s proposed Data (Use and Access) Bill,[86] including:

- Enabling law enforcement agencies receiving biometric data from overseas partners to indefinitely retain this data, where the data is relevant to national security and has been pseudonymised (Clause 127).

- Granting new regulation-making powers for the Secretary of State with regards to automated decision-making (ADM). The bill introduces new powers for the Secretary of State to determine ‘when meaningful human involvement [in relation to automated decision-making] can be said to have taken place in light of constantly emerging technologies, as well as changing societal expectations of what constitutes a significant decision in a data protection context’ (Clause 80). This could give government the powers to waive restrictions on the use of ADM where novel biometric technologies cannot easily be influenced by a human in the loop. This could in theory apply to black-box inferential biometric applications where it is not clear to operators how models have made their inferences.

- Changing clauses relating to special category data, which biometric data currently falls under when it is processed ‘for the purpose of uniquely identifying a natural person’.[87] Proposed changes include giving powers to the Secretary of State to ‘add new special categories of data, tailor the conditions applicable to their use, and add new definitions, if necessary, to enable the Government to rapidly respond to future technological and societal developments’[88] – and potentially remove added categories at a later date.

As evidenced above, much parliamentary attention has been given to proposals for supporting biometrics use and stimulating associated markets, but comparatively little focus has been given to strengthening safeguards for these applications. However, several parliamentarians have expressed concerns around this lack of safeguards and have called for increased regulation and guidance – in particular, the House of Lords’ Justice and Home Affairs Committee.

In March 2022, the committee published its report Technology Rules? The advent of new technologies in the justice system, calling for a number of measures for governing emerging law enforcement technologies, including biometrics. This included developing ‘detailed regulations setting minimum technological standards’ as well as mechanisms for pre-deployment certification of technologies procured by police; mandating participation in the Algorithmic Transparency Recording Standard; and establishing regional ethics committees.[89] In January 2024, the committee published an open letter on police use of LFR, calling for a new legislative framework, an independent regulator, and standards for pre-deployment communication.[90] Most recently, the committee concluded an inquiry into shop theft, which raised concerns about use of facial recognition by private companies equating to ‘privatised policing’ – and reiterated its view that ‘primary legislation embodying general principles and setting minimum standards is required.’[91]

The UK has also signed the Council of Europe’s Framework Convention on Artificial Intelligence and Human Rights, Democracy and the Rule of Law. Its fundamental objective is to ‘ensure that activities within the lifecycle of artificial intelligence systems are fully consistent with human rights, democracy and the rule of law’.[92] AI models using biometric data fall under the broad definition of AI systems within the treaty, which applies to both public authorities and private companies (such as facial recognition providers) acting on their behalf.[93] Principles particularly relevant to biometric surveillance include human dignity and individual autonomy, privacy, proactive notification that individuals are engaging with AI, public consultation obligations, and ensuring that individuals can register complaints.

UK standards and guidance

The UK’s biometrics laws are supplemented by a patchwork of regulatory guidance, ethical principles, and professional standards and frameworks. These governance mechanisms shape how biometric systems are developed and used in practice, and include:

- The Biometrics and Forensics Ethics Group (BFEG) principles:[94] Covers the use of biometric systems ‘that fall within the purview of the Home Office’. These principles encompass both high-level ethical principles (i.e. recommending that biometrics enhance public good, respect the dignity of individuals and groups, uphold data protection and equalities laws, etc.), as well as practical recommendations (i.e. recommending that systems are publicly accessible and explainable, based on robust scientific evidence, and subject to independent review before and after deployment).

- The UK digital identity and attributes trust framework: Sets out standards and terminology for ensuring digital identity services are ‘reliable, secure, and trustworthy’.[95]

- The Biometrics Institute Good Practice Framework:[96] Outlines good practice across strategic planning, procurement and operation of biometric systems. Access to the framework is limited to members of the institute, and is supplemented by other publications including the Ethical Principles for Biometrics and The Three Laws of Biometrics.

- Technical standards developed by national and international standards development organisations: This includes ISO standards for designing legal and ethical biometric systems[97] and supporting interoperability,[98] as well as BSI standards on biometric recognition[99] and ethical facial recognition use.[100]

- The ICO’s biometric recognition guidance:[101] as referenced above in ‘UK regulatory landscape’.

These publications are supplemented by several other forms of guidance more narrowly focused on surveillance and/or police use of biometrics. These include:

- The Surveillance Camera Code of Practice[102] and the Scottish Biometrics Commissioner Code of practice:[103] On the acquisition, retention, use and destruction of biometric data for criminal justice and police purposes.

- The College of Policing’s Live Facial Recognition Guidance:[104] Outlines watchlist practices, performance metrics, deployment conditions and key terminology for overt facial recognition.

- The College of Policing’s Authorised Professional Practice (APP), building on its general Code of Ethics: The draft Data Ethics APP and Data-driven technologies APP[105] were published in August 2024 for consultation. Other APPs such as the Code of Practice for the Police National Computer and the Law Enforcement Data Service offer guidance relevant to specific police systems underpinned by biometric systems.

- Local policies and guidance specific to police forces: For example, the Metropolitan Police’s Overt LFR[106] and RFR systems[107] policies, which guide deployment of the technology. They are due for review in September and August 2025, respectively.

As evidenced above, the UK has adopted a diffused approach to biometrics governance, where fundamental deficiencies in the UK’s legal framework (as identified by Bridges) are, in theory, addressed by local policies and standards. However, not all countries have taken this soft-law approach to biometrics governance. For example, the EU has developed a more comprehensive and statutory legal framework to govern biometric technologies – as detailed in Box 5 below.

Box 5: The European regulatory landscape

The foundational legal obligations underpinning biometrics legislation are set out in the European General Data Protection Regulation (EU GDPR). Other directives articulate additional safeguards for certain applications and contexts – including Regulation (EU) 2018/1725 of the European Parliament and of the Council[108] and Directive (EU) 2016/680 Art 3 (13) processing for law enforcement purposes[109] which cover public and law enforcement use, respectively.

However, most notably, European policymakers’ concerns around biometric technologies have shaped negotiations around the EU Artificial Intelligence Act (EU AI Act), which came into force on 1 August 2024 and takes a considerably harder line on certain biometric applications.

The EU AI Act is a risk-based regulation that distinguishes biometric systems based on use case and system architecture,[110] as well as the risks they present to the public’s fundamental rights and freedoms. Biometric applications considered to be highest risk under the Act include:[111]

- Emotion recognition systems for the purpose of identifying or inferring emotions or intentions of people based on their biometric data.

- Biometric categorisation systems that process biometric data to assign people to specific categories, such as sex, or behavioural or personality traits.

- Remote biometric identification systems for use in identifying people without their active involvement and typically at a distance, through the comparison of captured data with biometric data contained in a reference database. These systems are distinguished based on whether they operate in real-time or are ‘post-remote’ where the comparison and identification happens only after a significant delay.

Significantly, the EU AI Act bans some biometric applications, including real-time remote biometric identification by police in publicly accessible spaces; emotion recognition in workplaces and education settings; certain types of biometric categorisation; and all scraping of the internet to get facial images for biometric databases in the EU.[112] However, it should be noted that there are certain exemptions for law enforcement applications of biometric systems which are otherwise banned for use under the EU AI Act, for example, when there are imminent threats to life.[113]

Biometrics since Bridges: Does the UK governance landscape for biometrics comprise a ‘sufficient legal framework’?

In the preceding section of this report, we identified the host of local policies, standards and guidance which have been developed since the Bridges ruling in 2020, to support the legal implementation of police use of live facial recognition (LFR). In this section, we consider whether this current approach to governance – a diffused model, comprised of myriad guidance, policies and practice standards – adequately addresses and/or incorporates the mandatory practices for lawful police use of LFR set out by the Bridges ruling (see Annex 1).

To determine whether existing guidance and frameworks adequately capture the legal standards set out in Bridges, we analysed it against the two primary pieces of police guidance on LFR, specifically: (1) the College of Policing’s Live Facial Recognition Guidance and (2) the Metropolitan Police Service (MPS) Overt LFR Policy Document.

Our analysis finds:

- The College of Policing’s Live Facial Recognition Guidance covers some but not all of the legal standards set out in Bridges. However, the guidance delegates several powers to local police forces, which can result in uneven application of legal standards across forces.

- The Metropolitan Police created its own policy, the MPS Overt LFR Policy Document, to fill these gaps. This policy addresses some of the delegated gaps, such as giving clearer criteria for where and when LFR can be deployed.

- However, the MPS guidance allows for the creation of watchlists based on ‘reasonable grounds’ which allows for police officer discretion, risking subjective and discriminatory decision-making.

- While the MPS has developed local policies to clarify gaps in the College of Policing guidance, it is unlikely that all other regional police forces will have the capacity or understanding of LFR to do so, which can lead to inconsistent or risky deployment.

- Existing policies are specific to LFR, providing limited guidance on police use of other high-risk biometric technologies, including operator-initiated facial recognition (OIFR), retrospective facial recognition (RFR), voice recognition, gait recognition and biometric inference.

- These pieces of guidance address some but not all of the mandatory practices outlined in the Bridges ruling making the lawfulness of current LFR use unclear – particularly newer deployment types such as permanent LFR camera installations.

- Despite its insufficiency, police use of LFR represents the biometrics application with the greatest current level of governance oversight. It follows that other biometric technologies that carry equivalent or higher levels of risk, from RFR to emotion detection are subject to even less adequate governance.

The College of Policing’s Live Facial Recognition Guidance

Following the Bridges judgment, in March 2022 the College of Policing published its Live Facial Recognition Guidance, which aimed to provide clarity on what practices and safeguards must be implemented for lawful police use of LFR.

How does this compare to the legal standards set out by the Bridges ruling? (See Annex 2 for the full analysis). Overall, 11 out of 19 of the mandatory practices outlined by Bridges are addressed by the College of Policing guidance. These include practices such as: instantaneous deletion of facial images that do not match a police officer watchlist; requirements for Data Protection Impact Assessments and Ethical Impact Assessments that identify potential risks to human rights and discrimination; as well as proactive measures to address bias and discrimination, including consultation with affected groups.

However, five of the practices outlined in the Bridges judgment are only partly covered by the College of Policing guidance, due to vague and/or ambiguous language. For example, while the Bridges judgment maintains that LFR may only be used when deployment is strictly necessary for a specific law enforcement purpose, the College of Policing guidance maintains LFR may be used for any ‘intelligence or investigative opportunity with limited time to act’. This subjective and ambiguous wording provides scope for deployment under wide conditions.

Finally, three practices – specifically related to criteria for developing and deploying police watchlists – are not addressed in the College of Police guidance. Rather, the guidance delegates rules for watchlist development to individual police forces, to further define through their own policies and guidance. Delegating these powers to individual police forces creates potential risk of governance gaps and inconsistencies in approaches. However, these gaps can, in theory, be covered by local policies. The next section considers the Metropolitan Police Service’s (MPS) local policy to consider if, and how, these gaps are addressed.

Metropolitan Police Service (MPS) Overt LFR Policy Document

The College of Policing guidance, discussed above, delegates responsibilities around establishing clear criteria and processes for the development and deployment of police watchlists to local authorities.

The MPS Overt LFR Policy Document adequately addresses some of the gaps and ambiguities within the College of Policing guidance. For example, the Bridges judgment maintains that there must be limited officer discretion in determining where LFR is deployed. The College of Policing guidance delegates this responsibility to regional constabularies, to set out ‘where the LFR system may be deployed and for what purpose’.[114] The MPS guidance addresses this gap well, giving objective numerical and legal criteria on when LFR can be deployed – for example, articulating that it can be deployed in a 300–500-metre-wide ‘crime hotspot’, where the crime rate and/or crime rate rise is in the upper quartile relative to other areas.

However, other mandatory practices delegated by the College of Policing guidance to regional forces are not adequately addressed by the MPS guidance. For example, the Bridges judgment outlines that police watchlists must be developed with 1) limited officer discretion, and 2) non-subjective criteria. The College of Policing guidance delegates this responsibility to local forces, to set out ‘criteria for developing a watchlist and possible sources for watchlists’. The MPS guidance identifies some criteria for the ‘sought persons’ that make up their watchlist database. While some of these criteria are clear and objective (i.e. where people are wanted by the courts, or where they have been convicted under the Terrorism Act 2000), one criteria opens up potential for ambiguity and an excessively broad interpretation – under the MPS guidance, someone can be placed on the watchlist ‘where there are reasonable grounds to suspect an individual is about to commit, is committing, or has committed a recordable offence’.[115]

The concept of reasonable grounds (enshrined in the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984) is controversial, with multiple studies finding this standard is ‘seldom adhered to by police with stereotypes possibly playing a role in informing their suspicions’.[116] The MPS guidance for conducting a reasonable grounds test maintains that ‘An officer must genuinely suspect that they will find the item searched for […] [and] it must be objectively reasonable for them to suspect this, given the information available to them’.[117] This test is inherently grounded in the judgement of individual police officers – contradicting the need to limit officers’ discretion in deciding who is placed on an LFR watchlist.

From the analysis above, it is clear that both high-level police guidance and local police policies address some but not all of the mandatory practices outlined in the Bridges ruling. This suggests that the fundamental deficiencies identified in UK law have not been adequately addressed by the patchwork of guidance, standards and policies published since the judgment – and that the current ‘diffused’ model for biometrics governance is lacking adequate safeguards and protections for the lawful deployment of biometric systems.

While some could contest this analysis and argue that the College of Policing guidance along with the MPS’s policy document do sufficiently address practices set out by Bridges, this does not represent a sufficient legal framework for wider biometrics use. This is because:

- While the MPS has developed local policies and procedures that aim to provide clarity on delegated practices set out in the College of Policing guidance, it is unlikely that all other regional police forces’ policies will have the capacity or understanding of LFR to do so. The MPS has been using LFR since before 2020 – as such, it can be expected that the MPS’s guidance and policies will be more developed, relative to other forces that are beginning to trial and develop governance measures for LFR.

- Existing guidance across LFR and other biometric surveillance technologies are seemingly insufficient to guide on-the-ground practice. A survey of police surveillance in open spaces in the Biometrics and Surveillance Camera Commissioner’s annual report[118] finds:

- ‘A lack of specific guidance can inhibit planning and investment in new and emerging technologies.’

- There is a ‘need for precision in regulations to sustain the use of [surveillance camera technologies] by relevant authorities.’

- There is a need for strengthening due diligence in procurement processes, which is relevant to Bridges case standards relating to procuring facial recognition systems free from technological bias.

- There are some governance frameworks outlining processes for the safe deployment of LFR. However, guidance and standards relating to emerging law enforcement use of other biometric surveillance technologies – such as voice recognition, odour, gait and gesture technologies[119] – are considerably less developed, despite the level of risk posed by these technologies.

- Individual police forces (e.g. MPS) work on a deployment-by-deployment basis when assessing the proportionality of LFR. As a result, they may fail to take into account the culminative risks of an increase in total use. For example, some boroughs of London are more targeted than others – with almost half of all deployments from 2020 –2024 taking place in Westminster or Croydon. As a result, there is a risk that in these areas there will be increasing public perception of pervasive surveillance monitoring, which could erode individuals’ rights of free assembly or expression due to fears over the potential consequences.[120]

Given the gaps identified above, the current diffused model of biometrics governance does not appear to sufficiently deliver against the mandatory requirements and legal standards set out in the Bridges judgment.

The current model is also particularly difficult to monitor and enforce. Responsibility for developing and implementing each policy or piece of guidance is delegated across a range of relevant actors, including regulators, policing bodies and central government, and no formal incentives to monitor or report on implementation and compliance exist.

Despite its insufficiency, live facial recognition use by police represents the biometrics application with the greatest current level of governance oversight. It follows that other biometric technologies and types of technology that carry equivalent or higher levels of risk, from retrospective facial recognition to emotion detection are subject to even less governance – and are even less likely to meet the types of tests established by Bridges to ensure their lawfulness.

The next section of this report proposes an alternative model, outlining a centralised approach to biometrics governance, which consolidates the diffuse set of guidance and principles into a single framework that is developed, monitored and enforced by a sole, dedicated body.

The case for comprehensive biometrics regulation: Outlining the risks of partial approaches

The analysis in this report demonstrates that since the Bridges ruling in 2020, there remain fundamental deficiencies in the UK’s legal framework for live facial recognition (LFR) and consequently for other, equally consequential biometric technologies.

A different approach to governance is needed, that meaningfully covers existing, frontier and future biometric applications. In this section, we consider an alternative, centralised model for biometrics governance, and outline what a comprehensive biometrics governance framework could look like. In summary:

- Focusing only on police use leaves private sector surveillance unchecked. Surveillance is a key use case for biometrics, but if a regulatory framework addressed only police use there would be a disconnect in the standards and safeguards applying to police and private sector deployments. The Surveillance Camera Code is an example of an effective existing regulatory mechanism that spans across both sectors on a related issue.

- Regulating mass surveillance technologies and ignoring inferential biometrics leaves a dangerous blind spot. Without including inference-based systems such as emotion analytics applications, a regulatory framework would not be able to address some of the most high-risk and ethically fraught applications of biometric technology.

- To meaningfully protect privacy, prevent discrimination and ensure accountability, regulation must cover police use, private sector surveillance and inferential biometric systems alike. Only a comprehensive approach can close loopholes, keep pace with technological developments, and safeguard public trust in how biometric systems are used.

How different governance approaches would cover current biometric applications

Figure 5: A comprehensive framework for police use, private sector surveillance and inferential biometric systems

While efforts to regulate biometric technologies have often focused on specific use cases, particularly police surveillance, limiting regulation to one domain while excluding others creates significant gaps in addressing the impacts of current applications.

A comprehensive framework must encompass police use, private sector surveillance and inferential biometric systems (shown highlighted in Figure 5 above). Leaving any one of these areas unregulated undermines the overall effectiveness of governance and fails to protect the public from harm.

Focusing only on police use leaves private surveillance unchecked

Biometric mass surveillance technologies, such as facial recognition, pose significant risks to privacy, equality and individual freedoms, regardless of whether they are used by police and public bodies or private companies. While law enforcement applications have rightly attracted regulatory scrutiny, private sector use of these systems in publicly accessible spaces, like retail and commercial buildings, is rapidly expanding without clear oversight or accountability.

Limiting a biometrics governance framework to solely address and govern police use of LFR (or wider biometrics applications) leaves private sector surveillance unaddressed, leaving a legal grey area around deployments by private actors, such as retailers, landlords, employers and entertainment venues – see Figure 6 below. The lack of legal equivalency creates perverse incentives for outsourcing law enforcement responsibilities to companies with fewer governance obligations, less democratic accountability and fewer incentives to uphold rights.

Figure 6: A biometrics governance framework solely for police use of LFR and wider biometrics applications

Excluding inferential biometrics from a new regulatory framework leaves a dangerous blind spot