An eye on the future

A legal framework for the governance of biometric technologies in the UK

29 May 2025

Reading time: 14 minutes

On the brink of mass rollouts of biometric technologies in the UK, this briefing summarises the key findings of our report An eye on the future, which examines trends in the deployment and governance of biometric technologies.

Key findings

- Biometric technologies are a powerful set of tools for measuring and inferring characteristics about people. These technologies come with an accordingly consequential set of risks to individuals, deployers and society more broadly.

- The deployment of biometric technologies is becoming increasingly prevalent across the UK. In recent years, facial recognition systems have been deployed in local schools to facilitate cashless payments, by mass retail chains to identify shoplifters, and by police forces on smartphones and using CCTV footage.

- Alongside mainstream deployments of facial recognition for surveillance, a new generation of equally invasive inferential biometrics has hit the market, such as Network Rail’s use of emotion recognition systems in train stations. This new generation of technologies claims to infer sensitive internal states like a person’s emotions, intentions, attention or truthfulness – often with low levels of scientific validity.[1]

- The highly fragmented nature of biometrics governance makes it very difficult to understand whether the most basic deployments of biometric systems, specifically live facial recognition (LFR) by police, are happening under a ‘sufficient legal framework’ and are therefore lawful. Our legal analysis shows that key guidance issued by police bodies does not fully cover the mandatory practices set out by the courts.

- Oversight and guidance for all other biometric technologies and deployment types (e.g. private sector surveillance, police use of retrospective facial recognition, or commercial applications boasting ‘emotion detection’ capabilities) is significantly less mature than existing guidance for LFR, making such deployments even less likely to be lawful. This lack of clarity in the regulatory framework leads to both risky deployments that operate without appropriate policies, guidance or standards; and slower adoption.

- This report identifies significant gaps and fragmentation across biometrics governance in the UK, the extent of which urgently necessitates the introduction of an alternative approach. We make six recommendations that would consolidate mandatory practices and legal requirements into a dedicated biometrics regulatory framework and designate a centralised regulatory body to act as the single source of oversight, clarity and enforcement.

What are biometrics?

Biometric data (shortened to ‘biometrics’) is personal data, often taken from or relating to a person’s body (biological biometrics) or behaviour (behavioural biometrics), that can be used to uniquely identify or categorise them. Biological biometrics include fingerprints, iris scans, voice recognition and facial recognition; while behavioural biometrics include traits like gait analysis or keystroke analysis. Biometric technologies use biometric data to infer information about people – for example, their identity; their characteristics such as gender, age or race; or even assumptions about their internal states like their mood, intention or truthfulness.

Biometrics trends: a picture of growing use

- Existing deployment types of biometric technologies are becoming more pervasive. For example, live facial recognition (LFR) is being used by an increasing number of police forces[2] and shops.[3] More LFR systems are being installed permanently, rather than as temporary deployments.[4]

- Biometric technologies are being deployed in new public and digital spaces, e.g. at public transport stations for situational awareness and advertising[5], and in workplaces to clock people in and out.[6]

- Deployers are trialling new types of biometric applications at scale. For example, police are trialling facial recognition on bodycams, smartphones[7] and retrospectively on CCTV.[8]

- There is growing public access to digitally provided facial recognition services – e.g. PimEyes, a facial recognition website that allows users to identify all images of a person on the internet given a sample image – with evidence of informal use by public bodies such as the police.[9]

- A new generation of biometric technologies that claims to infer sensitive internal human states – like emotions, attention, intention or truthfulness – is hitting the mainstream market.[10]

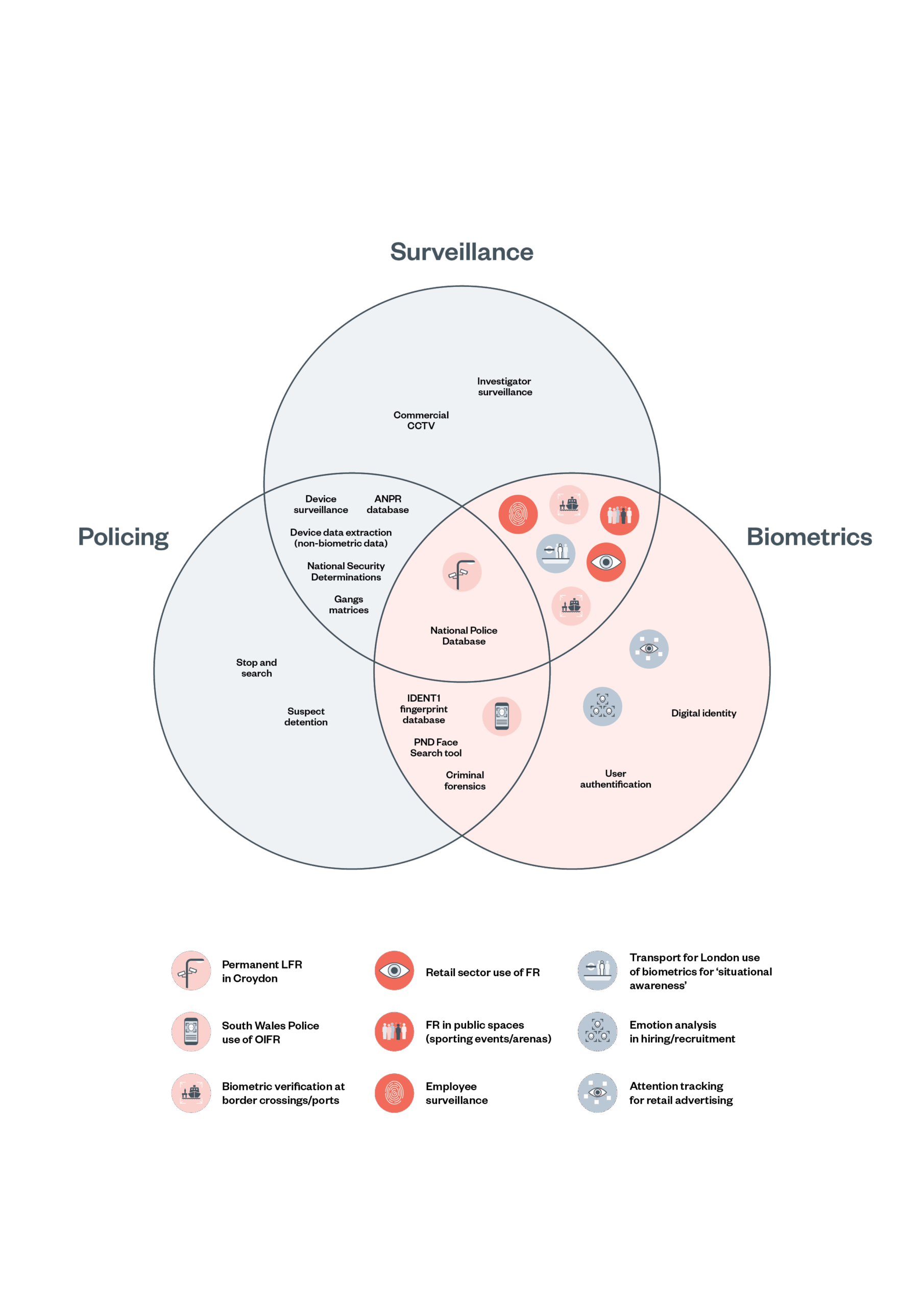

Figure 1: Current uses of biometrics in the UK

The governance gap

- The UK’s current approach to biometrics governance is diffuse – comprising a patchwork of law, guidance, standards and regulators. Biometric data is regulated in part by the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO), but its impacts are also governed by human rights and equality law.[11]

- The specific application of existing laws to live facial recognition (LFR) by police was considered by the courts in the 2020 Bridges judgment, which described the mandatory practices and legal requirements necessary for such use to be lawful: setting out what constitutes a ‘sufficient legal framework’. It identified ‘fundamental deficiencies’ in the UK’s legal framework, which made South Wales Police’s use of LFR unlawful.[12]

- Institutions have tried to fill the gaps in the legal framework through supplementary guidance and standards. However, our legal analysis shows that key guidance issued by police bodies does not fully cover the mandatory practices set out by the courts. These documents are developed and owned by a diffuse set of actors, including regulators, policing bodies and central government.

- These arrangements make it very difficult to know if even the most basic deployments of LFR by police are lawful. Both policymakers and police forces have criticised this model as insufficient and noted its inhibitory effect on legitimate deployment.

- The lack of clarity around LFR deployment points to a much bigger gap around the lawfulness of other deployment types (for example, police using facial recognition retrospectively on CCTV footage) and newer biometric technologies, such as those that claim to infer internal emotional states. Given the much less mature governance framework around these applications, any given deployment is even less likely to occur within a ‘sufficient legal framework’ and thus be lawful.

The existing governance of biometrics is widely seen as inadequate

‘If we want to properly protect the privacy and rights of our citizens as well as realise the potential benefits of these types of technology now and in the future, what we need is for government to get a sensible grip on it in terms of oversight and regulation.’ [13]

Fraser Sampson, Biometrics and Surveillance Camera Commissioner, 2023

‘We do not consider the current methods of oversight sufficient … We believe that, as well as a clear, and clearly understood, legal foundation, there should be a legislative framework, authorised by Parliament for the regulation of the deployment of LFR technology.’ [14]

Justice and Home Affairs Committee letter to Home Secretary, 2024

‘I have spoken to senior police leaders about the matter, and some believe that the lack of a specific legal framework inhibits their use of the technology and dampens willingness to innovate.’ [15]

Minister of State for Policing, Crime and Fire Prevention Dame Diana Johnson, November 2024

Governance options: what kind of governance is needed?

- A patchwork approach to biometrics regulation is no longer adequate. The risks posed by biometric technologies are not limited to a single sector or use case. Instead, they arise from the combined effects of widespread deployment; opaque decision-making; and the growing use of sensitive data to make decisions, predictions or assumptions about people.

- A comprehensive framework must encompass police use, private sector surveillance and inferential biometric systems (shown highlighted in orange in Figure 2 below). Leaving any one of these areas unregulated would undermine the overall effectiveness of governance, fail to protect the public from harm, and maintain uncertainty around the use of these technologies that will slow legitimate adoption.

- Limiting biometrics regulation to one domain while excluding others creates significant gaps in addressing the impacts of current applications. For example, focusing only on police use would leave the risks of facial recognition use for private surveillance unaddressed. While law enforcement applications have rightly attracted regulatory scrutiny, private sector use of these systems in publicly accessible spaces – like retail and commercial buildings – is rapidly expanding without clear oversight or accountability.[16]

- Similarly, excluding inferential biometrics from a new regulatory framework would leave a dangerous gap. These systems are often built on flawed or unproven science yet are increasingly being used in areas such as situational awareness, attention tracking and emotion analysis in high-risk use cases like recruitment and education.[17]

Figure 2: A comprehensive framework for police use, private sector surveillance and inferential biometric systems

Policy recommendations for a comprehensive legal framework

The UK government should develop a comprehensive, legislatively backed biometrics governance framework that gives effect to the recommendations below. The framework should:

- Be risk-based and proportionate, with tiered legal obligations depending on the risk level of the biometric system – analogous to the categorisation of different biometric systems in the EU AI Act.

- Specify safeguards in law for biometric technologies that build on those provided in existing regulation such as data protection law. This includes but is not limited to:

- transparency and notification requirements on vendors and deployers

- mandated technical standards relating to efficacy and discrimination

- obligations for system testing and monitoring; access to redress for individuals

- conditions on deployment and specific risk mitigation measures.Different measures would only apply to biometric applications posing a relevant level of risk, ensuring proportionality of compliance requirements. Risk categorisation and safeguards may need to be adaptable depending on the deployer (e.g. public vs private sector) as occurs with other frameworks such as GDPR.

- Adopt the definition of biometrics as ‘data relating to the physical, physiological or behavioural characteristics of a natural person’ to ensure consistency with existing legal frameworks and that newer applications like inferential biometrics are addressed. It should also allow for new categories of biometric data and system definitions to be added and removed over time, for example, through secondary legislation.

- Establish an independent regulatory body to oversee and enforce this governance framework. This could be achieved by broadening the remit and/or resources of existing regulators (e.g. the Biometrics and Surveillance Camera Commissioner (BSCC), or by establishing a new regulatory body).

- Grant the independent regulatory body with powers to develop binding codes of practice specific to use cases (e.g. a code of practice on inferential biometrics, or biometric applications of forthcoming 6G sensing technologies).

- Task the independent regulatory body, in collaboration with policing bodies, to co-develop a code of practice that outlines deployment criteria for police use of facial recognition technologies in policing, including live, operator-initiated and retrospective use. This code of practice should address the ambiguity and subjectivity of criteria within current guidance and ensure consistency across police deployments.

Acknowledgements

This briefing was adapted from the Ada Lovelace Institute report An eye on the future: a legal framework for the governance of biometric technologies in the UK. The report was lead authored by Nuala Polo, with substantive contributions from Jacob Ohrvik-Stott, Michael Birtwistle, Natasha Stallard and Sohaib Malik. We would like to thank Samuel Stockwell for taking the time to review an early draft of the report, and for offering his expertise and feedback on recommendations.

Footnotes

[1] Sam Stockwell, Megan Hughes and Carolyn Ashurst and Nóra NíLoideáin, ‘The Future of Biometric Technology for Policing and Law Enforcement’ (Centre for Emerging Technology and Security) <https://cetas.turing.ac.uk/publications/future-biometric-technology-policing-and-law-enforcement> accessed 28 May 2025.

[2] Masha Borak, ‘UK Police Promise More Fingerprint Matching, Facial Recognition in Efficiency Revamp | Biometric Update’ (17 November 2023) <https://www.biometricupdate.com/202311/uk-police-promise-more-fingerprint-matching-facial-recognition-in-efficiency-revamp> accessed 28 May 2025.

[3] ‘Joint Letter to UK Retailers Regarding the Potential Use of Facial Recognition Technology (FRT) within Their Stores | Privacy International’ <http://privacyinternational.org/advocacy/5351/joint-letter-uk-retailers-regarding-potential-use-facial-recognition-technology-frt> accessed 19 May 2025.

[4] BBC News, ‘Facial Recognition: Cameras to Be Mounted on Croydon Street Furniture’ (BBC News, 30 March 2025) <https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c5y913jpzwyo> accessed 28 May 2025.

[5] Abigail Opiah, ‘UK Train Stations Trial Amazon Emotion Recognition on Passengers | Biometric Update’ (18 June 2024) <https://www.biometricupdate.com/202406/uk-train-stations-trial-amazon-emotion-recognition-on-passengers>

[6] ICO, ‘ICO Orders Serco Leisure to Stop Using Facial Recognition Technology to Monitor Attendance of Leisure Centre Employees’ (7 February 2025) <https://ico.org.uk/about-the-ico/media-centre/news-and-blogs/2024/02/ico-orders-serco-leisure-to-stop-using-facial-recognition-technology/>

[7] South Wales Police, ‘Welsh Police Forces Launch First Facial Recognition Mobile App’ (13 December2024) <https://www.south-wales.police.uk/news/south-wales/news/2024/december/welsh-police-forces-launch-first-facial-recognition-mobile-app/>

[8] BBC News, ‘Essex Police Make Three Arrests during Facial Recognition Trial,’ (BBC News, 26 October 2023) <https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c51jzy42p19>

[9] ‘PimEyes: Face Recognition Search Engine and Reverse Image Search’ <https://pimeyes.com/en?utm_source=open%20graph&utm_medium=social&utm_campaign=open_graph> accessed 23 April 2025.

[10] Huw Roberts, ‘Inferential Biometrics: Towards a Governance Framework’ (Tony Blair Institute for Global Change 2022) <https://institute.global/insights/politics-and-governance/inferential-biometrics-towards-governance-framework> accessed 31 March 2025.

[11] Equality and Human Rights Commission, ‘An Update on Our Approach to Regulating Artificial Intelligence | EHRC’ (30 April 2024) <https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/media-centre/news/update-our-approach-regulating-artificial-intelligence> accessed 28 May 2025.

[12] R (Bridges) vs Chief Constable of South Wales Police, (2020) EWCA Civ 1058. https://www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/R-Bridges-v-CC-South-Wales-ors-Judgment.pdf

[13] Biometrics and Surveillance Camera Commissioner, ‘Report Finds “worrying Vacuum” in Surveillance Camera Plans’ (GOV.UK, 30 October 2023) <https://www.gov.uk/government/news/report-finds-worrying-vacuum-in-surveillance-camera-plans> accessed 27 May 2025.

[14] The Justice and Home Affairs Committee, ‘’Letter Regarding the Outcome of the Committee’s Investigation into the Use of Live Facial Recognition (LFR) Technology by Police Forces in England and Wales’ (26 January 2024)< https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/43080/documents/214371/default/>

[15] Hansard HC Deb. vol. 765 col. 229WH, 13 November, 2024. Available from: https://hansard.parliament.uk/Westminster%20Hall%20Debate/2024-11-13/debates/E334DF95-2313-4AAC-AA25-D34F8F7C8DD5/web/

[16] “Joint Letter to UK Retailers Regarding the Potential Use of Facial Recognition Technology (FRT) within Their Stores.” Accessed May 19, 2025. http://privacyinternational.org/advocacy/5351/joint-letter-uk-retailers-regarding-potential-use-facial-recognition-technology-frt.

[17] Sam Stockwell, Megan Hughes, Carolyn Ashurst and Nóra NíLoideáin, ‘The Future of Biometric Technology for Policing and Law Enforcement: Informing UK Regulation’ CETaS Research Reports, March 2024.

Image credit: Daisy-Daisy

Related content

An eye on the future

A legal framework for the governance of biometric technologies in the UK

Countermeasures

The need for new legislation to govern biometric technologies in the UK