The value of childhood

The commercialisation of children's play and entertainment on data-driven platforms

4 November 2025

Reading time: 11 minutes

This article was commissioned by the Ada Lovelace Institute as part of its research for the Nuffield Foundation’s Grown Up? Journeys to Adulthood project.

Over the last decade, Revealing Reality, a UK multidisciplinary research agency, has conducted ethnographic work with hundreds of UK children and their families to study how the changing digital landscape is transforming childhood.

Two of our projects, Children’s Media Lives and Children’s Data Lives, conducted for Ofcom and the Information Commissioner’s Office respectively, have highlighted that the most significant digital-driven change in children’s lives is the commercialisation of childhood. This refers to the ways in which companies accrue profits from children’s engagement on play or entertainment platforms.

Besides traditional advertising and interfaces to collect and sell user data, influencer sponsorships, product placement, in-app stores and other techniques designed to encourage spending have become part and parcel of play and entertainment websites. If we consider that 66 per cent of children in the UK use social media and 51 per cent of under 13’s have their own profile we can say that commercial environments have become a core part of childhood.

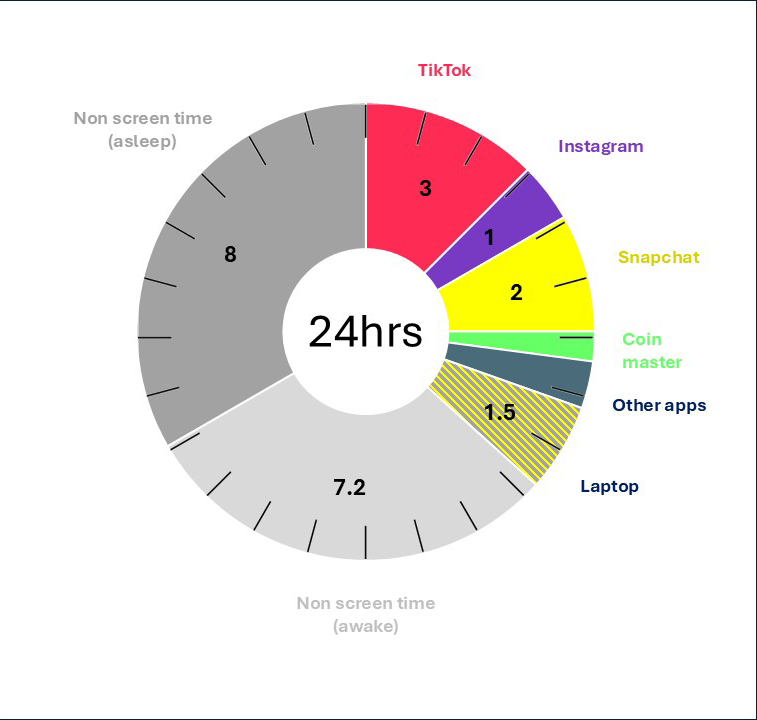

Suzy, 12, spends an average of seven hours a day on her phone, with TikTok as her most-used app. She describes scrolling before bed as ‘going down a rabbit hole’ – frustrated about the time spent on her device but drawn to the content.

On TikTok, she watches lifestyle and fashion-related videos. Recently, she bought a jumper from Adanola after seeing it in an influencer’s sponsored post. She also sees videos of young children marketing skincare products: ‘Wee girls that want to be grown up. Wee girls using retinol, wee girls buying Drunk Elephant.’

The short-form content has affected how she watches other media: ‘I find it really hard to watch movies. […] I just go on my phone, and I don’t even realise it, I’m just scrolling on TikTok then I look at the time and I’m like, “what the hell”.’

Participant from Children’s Media Lives, 2025 (Ofcom)

Platforms and online games generate revenues through multiple channels, according to a system that hinges on user data. Attention spans, preferences, scroll habits, locations, ‘plus names’, contact details and uploaded images power the personalisation of feeds, targeted ads and feature design, creating a feedback loop. The content shown shapes engagement, generating preference data that, in turn, shapes future content and increasingly precise marketing.

In this article, we explore entertainment and play as two aspects of childhood now shaped by commercial digital environments – drawing from over a decade of ethnographic research with children and families, and zooming in on findings from Children’s Media Lives and Children’s Data Lives.

Entertainment: from embedded values to embedded marketing

The online entertainment platforms most popular with children – TikTok, YouTube, Instagram – are designed to keep users engaged, but there is minimal oversight on the developmental impact of their content. Parents struggle to monitor highly personalised feeds, and regulators focus on removing harmful content more than ensuring that what remains benefits children. Platforms operate in a regulatory gap, which leaves children navigating digital environments primarily designed for engagement and profit rather than users’ wellbeing.

A cause and effect of platforms’ business models has been a shift in the subject of children’s entertainment: from stories, often with some sort of moral message, to fragmented content designed for clicks.

Prior to the introduction and the transition to digital television, five main public service broadcasting (PSB) channels dominated UK TV viewing. Children mainly consumed content that had been approved as suitable for them, with PSB channels operating within values that prioritised the public good, including what is considered to be beneficial and appropriate for children.

Commercial media products like books, newspapers and films were incentivised to be child-appropriate and often carried moral messages aiming to explore themes of right and wrong. While there was not always consensus about what was appropriate, parents and guardians could easily track what children were exposed to and make active choices about what they felt was suitable. If producers strayed too far from the values parents expected to see upheld, many children wouldn’t be taken to view the film or be bought the book, or the TV would be turned off.

In the first few years of Children’s Media Lives – a longitudinal ethnographic research project tracking a cohort of children since 2014 – we found that watching TV with their family was a common thing for children to do. As the years went by, it became far more unusual and in 2018 we reported that consuming content had become more of a solo activity.

Individual content consumption on personal devices and via tailored feeds is harder for parents and gatekeepers to monitor or curate, which in turn removes the incentive for content producers to consider societal values or develop meaningful stories.

Short-form video platforms, like TikTok and YouTube Shorts, serve feeds of clips, often just seconds long, splicing together unrelated videos, with the content rapidly tailored to whatever keeps the user most engaged.

Some of the older children involved in Children’s Media Lives describe their TikTok feeds as ‘random’ – content with no plot, made-up words, and little meaning beyond social media.

In our interviews we found that children themselves recognise this as problematic: the rise of the term ‘brain rot’ among young people reflects a growing awareness that much online content lacks substance or value. In our research, children frequently reported regretting spending time watching such content as soon as they put their devices down.

In a notable change, this type of social media does not feature dedicated and well-labelled ad breaks, as on broadcast TV. Content producers tend to seamlessly embed selling into entertainment via sponsorships, brand endorsements and product placement.

Children struggle to distinguish between entertainment and marketing when the boundaries are deliberately blurred, with influencers positioned as trusted friends whose product recommendations feel like personal advice rather than paid promotion.

During one interview, Keeley, 8, a Children’s Media Lives participant, showed researchers a ‘Beyond Family’ YouTube video featuring Amazon products. Keeley was clearly enjoying it. Yet when a separate Amazon pop-up interrupted viewing, she exclaimed: ‘I hate ads!’ This indicates the blurred line between clearly labelled marketing content (i.e. a pop-up advert) and more subtle forms of marketing (i.e. sponsored videos).

As mentioned already, the commercialisation of childhood hinges on data collection and extends beyond products sold on platforms. Children are mostly unaware of the data transactions platforms are built on. In Children’s Data Lives, we’ve found that even older teenagers have limited understanding of how their personal information is collected and monetised.

Children are unknowingly participating in a system where their profiles, viewing habits and preferences are packaged and sold to brands, who then use entertainment platforms to target users with increasingly sophisticated marketing.

Play: from community playgrounds to commercial platforms

With regards to changes in how children play, over the years we’ve observed a clear shift: play has moved indoors and onto screens.

When Children’s Media Lives started in 2014, although gaming and social media platforms were already popular, many of the children we spoke with spent evenings and weekends playing outdoors, going to various clubs and cultivating hobbies. This year, we found that many spend substantial out-of-school time online.

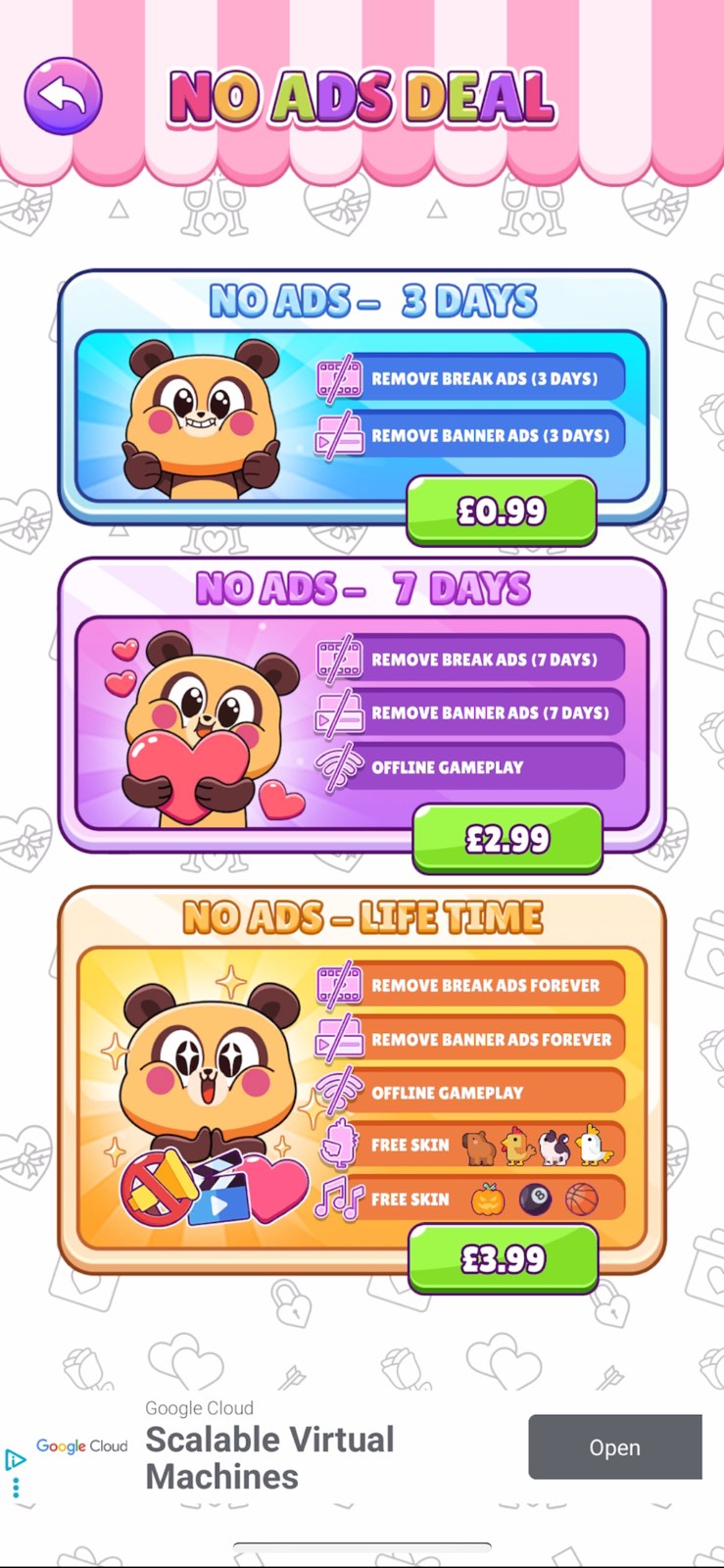

In 2015, year two of Children’s Media Lives, we noticed that the business models of games had started to diverge and follow two different paths. Traditional video games adopted a ‘pay-to-play’ model, where players pay a substantial upfront cost for a complete experience. These games usually take hours to complete and feature narrative arcs that lead players through a story. At the same time, we witnessed the rise of ‘pay-to-win’ games. These are free to download but designed to encourage ongoing spending on coins, skills or levels that offer progression or advancement, often accompanied by in-game advertising.

In 2025, the distinction between the two gaming models has largely collapsed. Both paid and free games are increasingly commercialised. Children encounter advertising, sponsorships, and spending opportunities regardless of whether they’ve already paid for the game.

Many online games and platforms could serve as examples, but its Roblox that overwhelmingly dominates children’s digital play. This hugely popular online platform combines gaming with social interaction and has achieved remarkable reach, reporting an average of 82.9 million daily active users in 2024 alone.

Roblox is an open platform on which anyone can create games, hangouts and experiences, though the most successful ones are usually supported or owned by commercial partners. Children use it to play games as well as talk to other people in virtual social spaces, making it both a social network and a gaming platform.

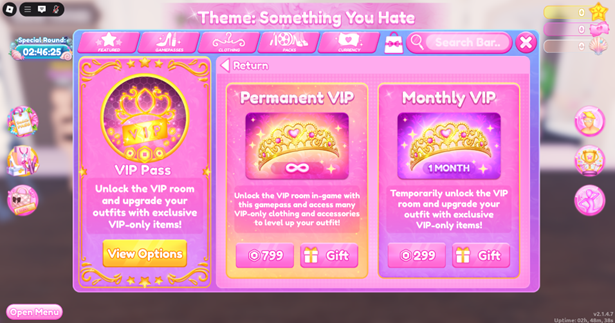

Users log in, choose from a vast menu of games and complete set activities to earn rewards or ‘Robux’, the platform’s in-game currency which can also be bought with real money. They can customise their avatars with outfits and accessories, many of which require Robux to access.

One of our Children’s Media Lives participants, Zak, 14, said he often spends most of his £20 weekly pocket money on Roblox, buying VIP access, character outfits and game upgrades.

If children aren’t seen to be spending on the platform this can be embarrassing for them among their peers. We heard from children that players with the default, unpaid-for avatars and outfits are seen as poor or uncool – they are ‘bacons’ or ‘noobs’. Children see their avatars on Roblox as an extension of themselves and making sure those avatars look good has replaced social indicators like having the latest trainers at school. Roblox and similar platforms are the places where children now socialise, get clout, show off and impress their friends.

The design of the platform reflects this trend: its online experiences encourage users to buy and sell digital features and physical goods. Major brands like Fenty Beauty, Gucci, Alo Yoga and e.l.f. Cosmetics sponsor games, offering purchasable items or selling physical products. Even free games on the platform encourage spending through ‘skins’, extra lives or cosmetic upgrades.

Environments like Roblox, Fortnite, NBA 2K or EA Sports FC (formerly FIFA) do all they can to engage children and have effectively replaced the playground.

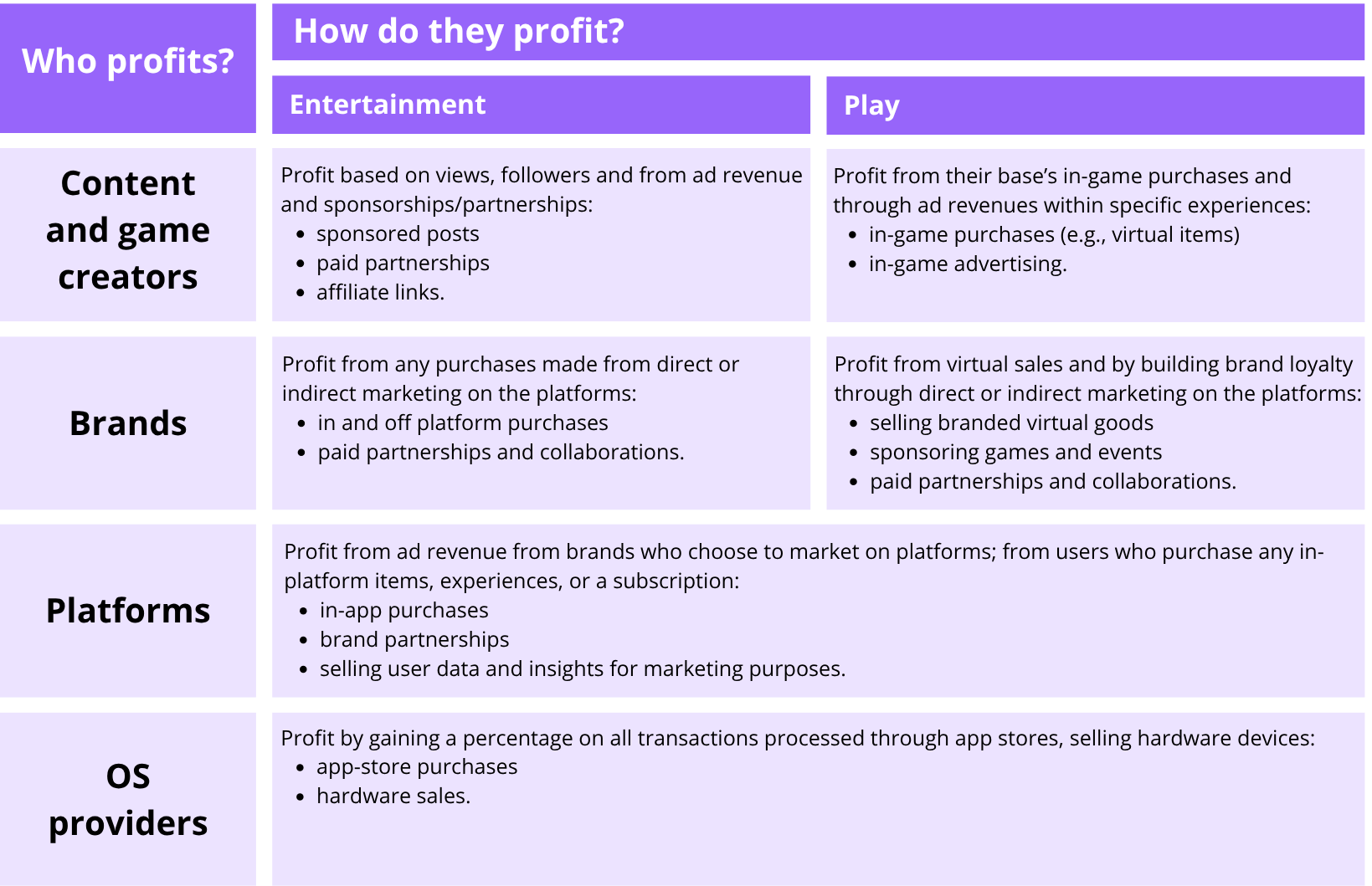

As in the case of entertainment platforms, the commercialisation of play revolves around an ecosystem where every actor, from game creators, to brands, to platforms, to OS providers, has a financial stake in keeping children engaged and spending, and none of them are incentivised to prioritise children’s wellbeing over profit.

What kind of adulthood follows a commercialised childhood?

You know the old saying: it takes a village to raise a child. Villages had a vested interest in children doing well. Communities enforced shared values and provided moral guidance to ensure children were brought up according to what they believed was right. It was by no means perfect, but the role once played by villages is increasingly being filled by companies and the commercial platforms they create.

The difference is fundamental: companies aren’t driven by values that prioritise children’s wellbeing. Regulators, by design, focus on preventing specific harms – removing dangerous content, ensuring fair markets, etc. – addressing what shouldn’t happen rather than what should. But there is little to no oversight on what kind of childhood we, as a society, want children to have.

The internet is no longer a space you can simply visit and then log off from; it is integrated into almost all aspects of life, society and culture. We’re watching the first generation of people growing up while playing and seeking entertainment in spaces designed to capture their attention, harvest their data, or get them to spend money. This doesn’t stop at play or entertainment: educational apps and management platforms in schools are gamifying learning, reducing progress to scores and collecting student’s data.

We’ve recently been exploring how young adults approach relationships, with some seemingly struggling with intimacy or relationship expectations. We can’t definitively attribute their challenges to their digital childhood. However, this raises questions about the impact that spending one’s formative years in environments designed to capture attention rather than nurture development can have on a person.

If childhood is increasingly mediated through commercial platforms, the issues at stake go beyond how children are spending their time. We should ask who benefits from this, what values are being prioritised, and what kind of adulthood comes after a commercialised childhood. What we do know is that the systems that know children best, right now, are the ones most motivated to profit from them.

The views expressed in this piece are of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Ada Lovelace Institute.

Related content

A learning curve?

A Iandscape review of AI and education in the UK

Learning and teaching with AI

A call for a rights-respecting approach