Examining the pros and cons of digital COVID certificates in the EU

Can an individualised data technology work in a public health context?

15 December 2022

Reading time: 12 minutes

In early 2021, the adoption of the EU digital COVID-19 certificates (hereafter DCCs), set up under EU Regulation 953/2021 (hereafter DCCR), sought to facilitate freedom of movement across European borders, while protecting public health in the midst of the pandemic.

At the time of writing, the winter wave of COVID-19 is circulating in Europe, though most of the protective measures have been rolled back. And while the DCCR remains in force until June 30 2023, the certificates are scarcely in use.

This blog post reviews the pros and cons of the implementation of DCCs, and the tensions that the DCCR has generated, and asks: what can we learn from this experience to manage future pandemics in Europe and elsewhere?

DCCs in the law and in practice

COVID-19 passes can be issued to citizens and residents of EU member states, if they have been fully vaccinated (a definition that changes according to the vaccine taken: for instance, in the case of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine, a person is fully vaccinated if they have received two shots and one booster shot), partially vaccinated plus have recently recovered from COVID-19 or have recently tested negative for COVID-19. This is the so-called .

DCCs have enabled people to travel internationally and, in some countries, access public spaces (restaurants, cinemas, etc.) that were otherwise forbidden, at times when the health crisis was acute.

While vaccination certificates have existed before – for example, WHO yellow cards – they have usually been exclusively paper-based. The system laid down in the DCCR aims to ensure that the passes issued in different member states are interoperable and verified across the EU. Interoperability is guaranteed through readable barcodes giving access to the relevant data, but there is no centralised database at EU-level and member states are solely responsible for ensuring that the information displayed on a pass is correct (see Recitals 18 & 52).

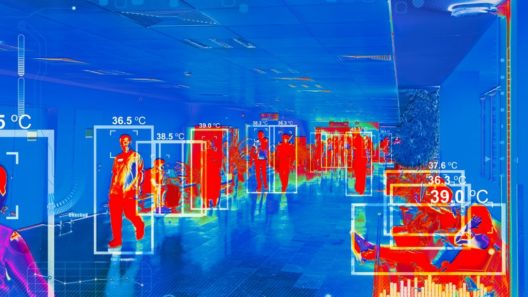

COVID-19 is an airborne infectious disease that spreads quickly, aided by the fact that many cases are asymptomatic, and thrives in community settings. The general response to and management of the pandemic has therefore required a communal approach. A vaccine or previous infection does not offer perfect protection against the spread of the virus, although both limit transmission at the community level.

How DCCs, which are de facto individualised risk assessment tools, have fitted in with communal measures is still unclear from a legal perspective.

Certifications’ positive outcomes

Unlike vaccine passports, which would usually be released only to vaccinated individuals, according to a 1G as opposed to 3G system, DCCs can be obtained following a biochemical test that demonstrates a form of immunity or the lack of infection. They are therefore available to a wider population, including those who cannot or refuse to be vaccinated. This means that the estimated population that (at the time of writing) is still not vaccinated is – in principle – not precluded from exercising rights such as freedom of movement.

A second salient aspect of DCCs is that they have been implemented as an alternative to more restrictive measures such as lockdowns.

Population-wide lockdowns apply indiscriminately to everyone, regardless of their immunity status – with the exception of workers considered to have key social roles. Certificates, instead, take a risk-based approach, relying on the assumption that the freedom of movement of those who pose less of a risk to public health should not be restricted – a notion that started circulating as early as spring 2020 with regards to those who had been recently infected.

After immunisation became more widely available in 2021 (by autumn 2021, almost two thirds of the EU population had been vaccinated at least once) through national vaccination campaigns, a significant number of people could be issued passes and exercise their freedom of movement nationally and across EU state borders.

With regards to whether DCCs genuinely operated as an alternative to lockdowns: while no nation-wide confinement has been imposed since the spring of 2021 in Europe, the exact relationship between the two measures is difficult to establish.

Lockdowns in EU countries were usually implemented when national healthcare systems risked being overwhelmed by the number of COVID-19 patients that required hospitalisation, something that was the case especially before vaccines became widely available.

While EU governments decided not to impose mandatory vaccination, a 2021 study suggested that the request for certification for travelling and accessing different social settings led to higher vaccination rates, especially as free testing (where testing is one of the ways to obtain a DCC) became less available.

This demonstrates that the policy of adopting DCCs played a role – even if an indirect one – in government efforts to lower the number of hospitalisations in healthcare facilities and avoid new lockdowns.

As a third point, so far the DCCR regime can be considered proportional to the goals pursued (i.e., freedom of movement and protection of public health), as the duration of the regulation’s applicability is limited. However, the period originally indicated in the sunset clause of Article 17 of the DCCR has recently been extended for another year – until 30 of June 2023 – according to the amended Regulation (EU) 2022/1034.

The extension was introduced without explaining how it would contribute to either the suitability or necessity of the measure. Clearly, continuous extensions of what was originally planned as a temporary measure will bring its proportionality into question.

To sum up, the positive effects of COVID-19 certifications are two-fold: a) improved vaccination rates and fewer hospitalisations, and b) contributing to implementing a less restrictive regime compared to general lockdowns or vaccination obligations (1G).

The downsides of DCCs and their legal framework

For a start, the virus today is different compared to the first half of 2021, when the DCCR was negotiated and adopted. Since the emergence of the Omicron variant, vaccines continue to protect against severe disease and death but have had limited effect on virus transmission. According to the DCCR, however, a COVID-19 certificate holder would still be considered ‘safe’ regardless of the epidemiological situation of their community (e.g., whether the cases or the levels of community virus spreading are rising or not).

Article 11 of the DCCR provides for some exemptions, e.g. states can impose additional requirements on pass holders when epidemiological conditions worsen, insofar as those requirements are necessary and proportionate for the purpose of safeguarding public health. However, the conditions of application of the article are vague and mostly relate to information obligations.

It is not clear whether the provisions of Article 11 are enough to account for the difficulty of calculating the risk of infection that an individual may pose. Instead the regulation has been harshly criticised as ‘fetishizing’ the idea of safe travel during a pandemic and as having the sole purpose of speeding up the return to ‘normal’ life. Indeed, among other factors, we should consider that the implementation of DCCs, when commonly in use in the EU, led to more social contact instead of social distancing, which could translate into more infections in a community.

Moreover, the lack of scientific certainty surrounding transmission and immunity brings up concerns about unequal treatment. A challenge that has been of the pandemic is whether linking freedom of movement to an immunological status constitutes discrimination.

As already mentioned, DCCs are less discriminatory than vaccination passports. However, it is not entirely clear whether also the DCCs’ 3G system can be discriminatory and towards whom. Mapping its effects and reviewing the case law of the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) will require further research. Additionally, to determine whether people have been discriminated in terms of their capacity to access public spaces, rather than crossing borders, we would need to look at EU member states’ domestic legislations.

For the moment, drawing on the case-law of the ECHR in HIV cases, most notably the 2011 decision in the Kiyutin case, the court understands public health measures as discriminatory if: a) they concern a particularly vulnerable group b) there is no reasonable and objective justification for the measures c) there is no opportunity for individualised assessment of a person’s situation and d) there is no ‘reasonable relationship of proportionality’ between the objective and the measure. Notably, the judgement refers also to scientific knowledge about the transmission modes of the virus at several points.

While it would be difficult to say that DCCs have concerned a particularly vulnerable group, unlike the stigma attached to persons living with HIV, minoritised groups such as migrants, and especially undocumented migrants, risk being further marginalised as they are less likely to be vaccinated or tested.

Moreover, the questions of reasonable and objective justification and individualised assessment remain pertinent. With testing rates and epidemiological surveillance slowing down since the beginning of 2022, the spread of COVID-19 has become more difficult to monitor. From a legal perspective, this might result in the differential treatment of individuals (according to whether they hold a pass or not) that does not rely on reasonable and objective basis, including scientific evidence, and may amount to discrimination.

Researchers also warn that policymakers are on a slippery slope toward unwarranted ‘bio-securitisation’ – meaning that when individualised risk assessment is difficult, access is dependent on a moralistic view of safe and unsafe bodies. However, so far, little empirical evidence (e.g. data or litigation) exists to confirm or reject this hypothesis.

Finally, overseas travellers have faced additional restrictions when entering the EU, when COVID-19 passes were required. This is especially problematic as only a has received at least one vaccination and, even in that case, subjects do not qualify as ‘safe’ according to the 3G system, unless they have also recently recovered from COVID-19. Furthermore, not all available vaccines are recognised by the European Medicines Agency, which has complicated the position of many travellers who have received, for instance, the Sputnik vaccine.

To sum up, certification has acted as a proof of safety without considering that the risk an individual poses to public health is not easy to calculate without considering the broader epidemiological context. This might lead to unfair outcomes, especially when considering marginalised populations and non-EU travellers.

How can the experience of DCCs shape future policy and legislation?

Eventually, through either medical or social means, the COVID-19 pandemic will end. Most likely, however, similar public health concerns will arise in the near future. Monkeypox has already emerged as a threat and polio is on the rise again.

We can learn valuable lessons from the use of certification over the last couple of years and anticipate future problems.

The COVID-19 pandemic has required scientists and policymakers to constantly revise their predictions. Communities with high vaccination levels may still experience high levels of infection transmission and, in these cases, the fact that an individual holds a certificate such as a DCC cannot tell us anything about the actual risk they pose to public health.

Going forward the following actions will need to be prioritised:

Decide what kind of certificate to require, according to health needs, in a lawful way.

In the case of the Omicron variant of COVID-19, immunity after infection appears to wane very quickly. As governments have switched from widespread testing to other means of epidemiological surveillance, if member states started widely requiring DCCs again, would they keep using the 3G system (vaccinated-recovered-tested), the 2G system (vaccinated, and either of the other two) or implement de facto vaccination obligation (1G)?

While the mandatory COVID-19 vaccination proposals have been quietly dropped in France and Austria, such ideas remain relevant in the light of possible future health threats. Should governments decide to implement a 1G system

Access to testing and vaccination must be ensured locally and worldwide.

Marginalised groups, such as refugees and people living in poverty, are less likely to have received vaccinations.

Many low- and middle-income countries have struggled to ensure a steady supply of testing materials and vaccination infrastructure. Experts are calling for better funding, and short-term as well as long-term measures to be adopted, including bringing vaccinations to people, instead of the other way around.

Enable widespread access to digital identities and infrastructure.

Since certification is reliant on digitised health records, these must be easily accessible to citizens and residents so that they can obtain the appropriate passes.

Solutions must be found to ensure access to vaccination for migrants and refugees, which is currently not mentioned under the DCCR. While some member states have been successful in vaccinating undocumented migrant communities, some kind of official registration number is often required by the present system, creating barriers for those who do not or cannot have one

Define the scope of access granted by the certificates in a consistent manner.

The EU has limited public health competences under Article 168 of the Treaty for the Functioning of the European Union and defining where certification is a condition for access (to which kinds of venues and under what circumstances) and where it is not will always be, for the most part, a task of the member states. This is likely to result in different applications of DCCs in different countries and related forms of discrimination.

Besides the competence limitations on health-related matters, however, the EU has played a merely technocratic rather than a lawmaking role, providing only the underlying infrastructure necessary to implement DCCs . This has led to member states adopting national legislation to ensure that public health measures are lawful. For example, Belgium has already passed its during an urgent pandemic situation, which gives a legal basis for the future use of health passes as well as other relevant measures.

In other words, while building the relevant infrastructure for the use of DCCs, the EU has so far failed to address the legal and societal consequences brought about by their use, such as vaccine hesitancy. This remains a major challenge should states continue to use certification schemes for the COVID-19 pandemic or other public health crises.

This blog post was commissioned in the context of our Health Data and COVID-19 technology research programme.

If you want to know more about the risks and benefits of vaccine passports, you may be interested in our previous work ‘Checkpoints for vaccine passports’.

Related content

Can digital immunity certificates be introduced in a non-discriminatory way?

New forms of technology are coming. How do we ensure they’re deployed in a way that conforms to equality regulation?

It’s complicated: what the public thinks about COVID-19 technologies

Lessons developers and policymakers must learn from the public about COVID-19 technologies.

Turn it off and on again: lessons learned from the NHS contact tracing app

The decision to delay the app’s launch is the right one.

Something to declare? Surfacing issues with immunity certificates

As the building of technical capacity for immunity apps and deliberation about deployment progresses, we surface six issues policymakers must consider