The dilemmas of delegation

An analysis of policy challenges posed by Advanced AI Assistants and natural-language AI agents.

11 November 2025

Reading time: 102 minutes

How to read this paper

This paper analyses some of the biggest policy challenges presented by Advanced AI Assistants, as well as providing an overview of what Advanced AI Assistants are and how they differ from other forms of AI, to be found in the introduction and the section ‘Introducing Advanced AI Assistants’.

- If you are interested in a summary of how Advanced AI Assistants might malfunction, behave unexpectedly or be exploited by bad actors, read the sections ‘Technical challenges’ and ‘Misuse challenges’.

- If you are interested in the privacy and cybersecurity implications of Advanced AI Assistants, or if you work in data protection or for a data protection regulator (such as the UK’s Information Commissioner’s Office), read the section ‘Privacy and security’ under ‘Systemic challenges’.

- If you are interested in the impact of Advanced AI Assistants on consumers’ ability to understand and navigate markets, if you work on competition policy or for a competition regulator (such as the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority), or if you are interested in the impacts of Advanced AI Assistants on democratic politics, read the section ‘Gatekeeping power, markets and democracy’ under ‘Systemic challenges’.

- If you are interested in the impact of Advanced AI Assistants on people’s cognitive capacities and mental wellbeing, or if you work in education policy, read the section ‘Deskilling and wellbeing impacts’ under ‘Systemic challenges’.

- If you are interested in the implications of Advanced AI Assistants for public service provision and the status and regulation of regulated professions, or if you work in public service policy or for a professional standards body, read the section ‘Professional and public services’ under ‘Systemic challenges’.

Executive summary

This paper sets out the policy challenges posed by a rapidly emerging class of AI systems that:

- can talk to their users

- can produce complex responses on the basis of those conversations

- and are typically highly personable and highly personalised to their users.

We call these kinds of systems Advanced AI Assistants, which we define as AI apps or integrations, powered by foundation models, that are able to engage in fluid, natural-language conversation; can show high degrees of user personalisation; and are designed to adopt human-like roles in relation to their users.

Advanced AI Assistants can be either (or both):

Agentic systems (AI agents) that take action directly on the world, which we refer to as:

- Executors, like OpenAI’s Operator,[1] which take action directly on the world on a user’s behalf.

User-focused systems that inform user action or act on the user themself, which we refer to as:

- Advisers, like legal instruction bot DoNotPay,[2] which set out advisory options for a user or the specific steps they need to take to accomplish a particular goal.

- Interlocutors, like the mental health app Wysa,[3] which aim to bring about a particular change in a user’s mental state, like an improvement in wellbeing or continued engagement with the app.

Advanced AI Assistants and AI agents

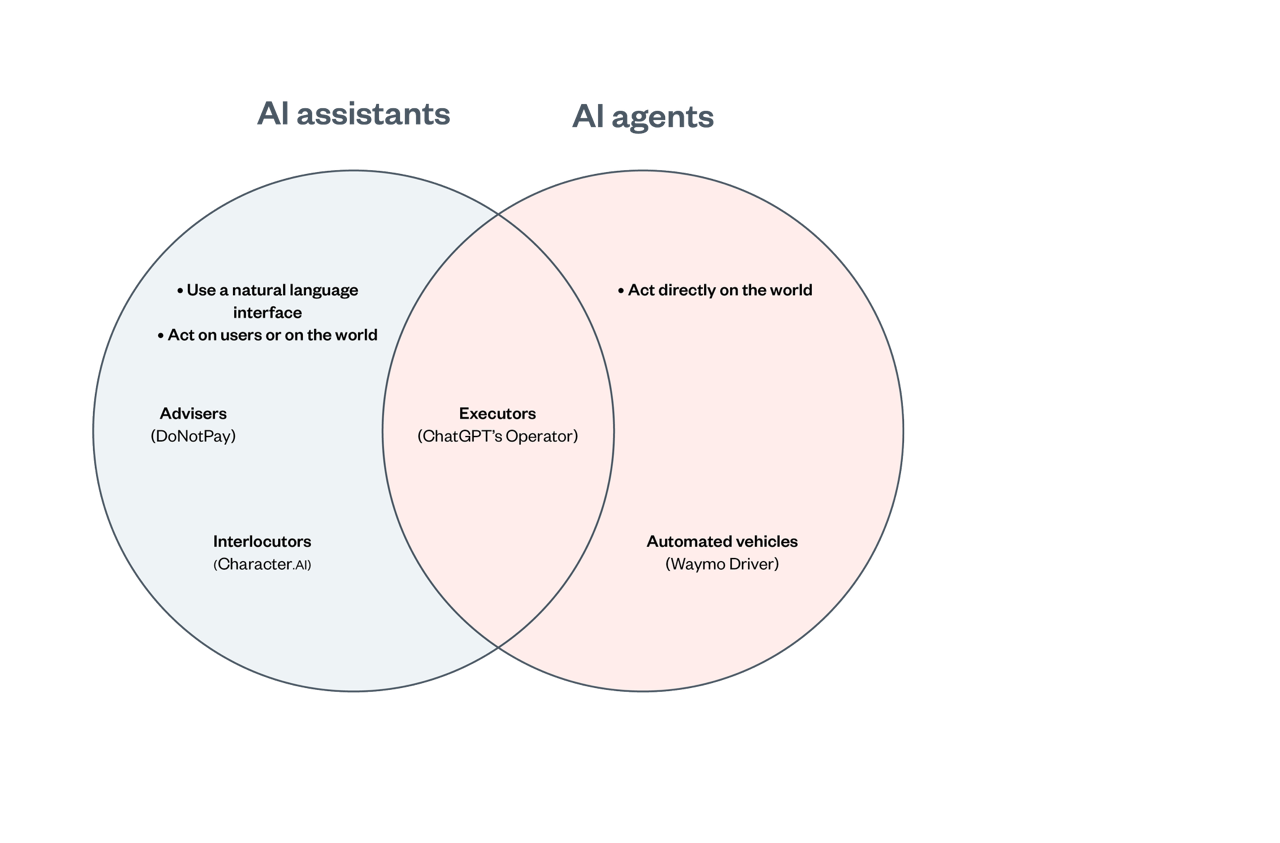

Advanced AI Assistants (‘Assistants’) are closely related to but not the same as AI agents.

- Assistants must have natural-language interfaces and need to be able to act on either their users or directly on the world.

- AI agents – which are defined by their ability to take goal-directed, autonomous action – do not need natural-language interfaces, but must be able to act on the world directly. For instance, many AI systems that control driverless cars are agents, despite not having natural-language interfaces.

Most agents offered commercially to businesses (e.g. for productivity) and consumers will tend to have a natural-language interface and act on either the user or the world, making them Assistants, to which the findings of this paper apply.

Readers may wish to think of most agents they are likely to have encountered as a subtype of Assistants.

Advanced AI Assistants are typically easy to use, highly personalised and ‘personable’, and capable of carrying out complex, open-ended tasks.

Assistants can be very persuasive and easy to trust. Because of their combination of ‘personality’ and personalisation, Assistants can be very easy for users to anthropomorphise, form emotional attachments with, and trust. In many cases, this makes Assistants very persuasive, meaning their outputs could meaningfully influence human action or decision-making. There is already ample (albeit anecdotal) evidence of people making life-changing decisions influenced in part by their interactions with Assistants.[4] [5]

Assistants are set to spread quickly. Assistants are increasingly readily available, being vigorously marketed by their developers and offering a set of features that could make them appealing both to businesses and individual users. They have been quick to reach scale via web and app implementations, alongside integration into existing apps, productivity suites and operating systems. As a result, they have the capacity to spread rapidly throughout our economies and societies.

In particular, Assistants could be used by members of the public far more than previous forms of AI, leading to a dramatic increase in the number and variety of tasks delegated to AI.

Assistants could become the principal means by which most people access the internet and interact with the digital world – as universal digital intermediaries – giving them substantial gatekeeping power over users.

Decision-makers in major tech companies and AI labs are predicting a future in which Assistants mediate most of our interactions with the internet and computers. Senior figures from Microsoft, Meta and Google all claim that instead of browsing and searching the internet, or directly using apps and software, most people will soon talk to an Assistant, which will interpret their requests, access relevant information and carry out tasks, and feed the results back to the user in a paraphrased, digestible format.[6] [7] [8] [9] [10] [11]

This is a model of computer use that would place Assistants in a position of subtle but enormous power. In some circumstances, it would amount to giving a single class of highly persuasive, personalised systems the ability to determine what information, viewpoints, ideas and options people are exposed to; how these are presented and framed; and how user orders and requests are interpreted.

This has implications not only for consumers, but for businesses and public sector organisations using Assistant outputs to inform decision-making.

If we want Assistants to benefit society, their diffusion will have to be managed carefully. The economic and societal impact of Assistants will be determined in large part by how the rollout of this powerful technology is handled. Managed and guided carefully, the spread of Assistants could bring significant economic and societal benefits. Badly managed or unmanaged diffusion of Assistants could – at best – fail to result in meaningful benefits, and – at worst – create significant long-term harms.

If the adoption of Assistants is not carefully managed in the public interest, this technology could:

- Fail to deliver the sustained, broadly felt economic benefits currently used to market their adoption.

- Present far greater risks to privacy and security than previous digital technologies.

- Distort markets, disempower consumers and exacerbate monopoly power.

- Exert powerful, hard-to-detect influence on users’ political views and understanding of the world.

- Lead to widespread cognitive and practical deskilling.

- Undermine people’s mental health and flourishing.

- Degrade the quality of some public and professional services.

- Call into question standards of quality, protection and liability governing professionals.

These problems could arise even if we make the very optimistic assumption that Assistants function exactly as advertised and are only used in accordance with the law.

Governments in the UK and around the world will need to rapidly develop a strategy to manage Assistants. Some of the challenges we outline in this paper are more extreme variations of problems posed by other forms of AI and digital technologies, while some challenges are more specific to Assistants. As such, their widespread use will require governments to accelerate existing work on the governance and direction of AI, and to rapidly develop policies to deal with the more novel challenges posed by Assistants.

In the absence of these policies, Assistants could become embedded in our societies and economies in ways that deliver little long-term economic or societal benefit, and entrench harms that are hard to reverse.

Introduction

AI is getting personal.

Advances in foundation models are leading to the development of applications and integrations able to engage users in natural, fluid conversation; deal with complex, open-ended tasks;[12] and display a high degree of personalisation and ‘personality’. These applications, which we refer to as Advanced AI Assistants (‘Assistants’), are designed to play particular, human-like roles in relation to their users.

Assistants (as we will refer to them throughout this paper) are being presented by their developers as a form of AI with the potential to transform the way we work, live and interact with digital technology.[13]

As champions of this technology are quick to point out, the development and widespread use of Assistants could come with a host of economic and societal benefits. Generalist Assistants, to which users can delegate thinking, research and (in some cases) action, could greatly enhance people’s productivity both inside and outside of work – giving users something equivalent to an automated PA. More specialised Assistants, developed to provide analysis and advice in fields such as law, medicine and mental health, could be instrumental in expanding access to professional expertise.

As a technology with the potential for – and that by some accounts demands – deep integration into our lives and economies, the embrace of Assistants also presents profound risks.

Taking full advantage of the labour-saving potential of Assistants is dependent on placing a high degree of trust in these systems. It also depends on sharing large amounts of personal or otherwise privileged information, and presuming that the advice they give and actions they take are correct, unbiased and in our best interests. Similarly, while the combination of ‘personality’ and personalisation makes Assistants easy and engaging to use, these features could foster practical and emotional dependency in users, as well as making Assistants powerful tools for manipulation.

Many of the resulting challenges are variations on themes that will be familiar to those working on broader AI and emerging technology policy. Like previous digital technologies, Assistants pose difficult questions around the relationship of human labour to capital, the beneficiaries of automation, and privacy. While these issues are by no means new, Assistants could introduce additional complications and shorten the timescales within which governments must develop responses to these disruptions.

Other challenges are more novel. At a structural level, the ability of Assistants to serve as gatekeepers to digital information and ideas, and to influence the views and behaviour of users, could – in the wrong circumstances – pose a profound threat to the integrity of free markets and democracy. And at an individual level, Assistants could contribute to high levels of practical and emotional deskilling and dependency, and damage the mental health of users.[14]

The window for addressing these challenges is closing quickly. While not yet ubiquitous, Assistants are already readily available, are being aggressively promoted by the tech industry, and promise to provide things the private and public sector desperately need.

Since the release of OpenAI’s GPT foundation models in late 2022, there has been an explosion of dedicated Advanced AI Assistant apps, providing users with advice and services ranging from help with the law and medical diagnosis to companionship and mental health support.

More recently, large technology companies have started to integrate Assistant features into their existing, general-purpose AI products. Both Anthropic’s Claude and OpenAI’s ChatGPT have agentic features, enabling these systems to take action directly on the world.[15] [16] In early 2025, OpenAI introduced ChatGPT features that enable users to make the app more personalised and endow it with a chosen ‘personality’.[17] Just as users of digital services have become accustomed to AI features appearing unprompted on otherwise familiar software, they may soon find AI-based services have morphed into forms of Assistants.

In addition to their ready availability, Assistants have features that could make them far more appealing to businesses and the public sector than previous forms of AI. In particular, Assistants’ reliance on a natural-language interface and their ability to deal with open-ended tasks could make them far easier (and less technically demanding) to integrate into existing business models and workflows than other forms of AI.[18]

In the UK, where businesses have been struggling with stagnant productivity since the late 2000s,[19] and where automation has often been stymied by low company-level awareness and technical know-how,[20] Assistants – which are easy to deploy, come pre-loaded on existing software platforms and promise to improve productivity – could look especially attractive.

This combination of push and pull factors (ready availability, proactive marketing and a demand for easy-to-use tools to improve productivity) could result in Assistants diffusing very quickly through our economies and societies.

Against a backdrop of limited AI-specific regulation, heavy industry marketing and hype, and adopter curiosity, the path of least resistance for Assistants may well be one of widespread adoption, subject to few ex-ante regulatory constraints. Given the issues and challenges posed by the technology – around value capture, surveillance, manipulation and dependency – such a laissez-faire approach to Assistants could expose our economies and societies to an unacceptable level of risk. At best, it could be economically transformative, spurring growth and expanding access to services. At worst, it could deliver a future in which we are dependent on AI systems that compromise our privacy, colour our view of the world and undermine our mental wellbeing – and in which those Assistants enrich only a small number of large technology companies.

Moreover, an unhealthy relationship with Assistants may be difficult to reverse once established. Those using Assistants could find it hard to go back to an Assistant-free existence – either due to fear of being left at a disadvantage compared to those still using them, or as a result of having recalibrated working and living patterns in ways that require these tools. As a result, individual users (and even policymakers) may find themselves with little leverage to push technology companies for better relationships with these systems.

Assistants could be on the cusp of spreading very quickly and, despite their positive potential, could be set to do so on terms that in the absence of countervailing forces would serve few others than their developers. Policymakers must actively manage the adoption of Assistants to ensure that harms are mitigated and benefits are fairly and broadly distributed.

Introducing Advanced AI Assistants

Our definition of Advanced AI Assistants

We define an Advanced AI Assistant as an AI application, powered by a foundation model, that primarily uses a natural-language interface and is capable of and designed to play a particular role in relation to a user that might otherwise be played by a human. Assistants are characterised by high degrees of personalisation and are typically configured to take on one (or more) of the following roles in relation to a user:

- an executor, acting directly on the world on behalf of a user

- an adviser, instructing a user on how to accomplish a particular task or realise a particular objective

- an interlocutor, interacting with a user to bring about a particular mental state.

We readily acknowledge that these categories are not perfect. In practice, there will be substantial overlap between executors, advisers and interlocutors, and there may be a degree of ambiguity as to which categories a given system falls into. In many cases, the actual uses of Assistants are likely to be very different to the uses for which they were designed or explicitly marketed. While some more specialised Assistants may be difficult to use outside their intended domain of operation, more generalist Assistants will be particularly prone to dual or off-label use.

Despite these limitations, we propose that thinking about Assistants as executors, advisers and interlocutors is useful for considering the specific policy and regulatory challenges they pose. The key advantage of this categorisation is that it helps make clear what the human analogue of a given Assistant might be, and therefore where we may already have norms, law or concepts that could be applied to the challenges in question.

For the purposes of brevity, at many points in this paper, we abbreviate ‘Advanced AI Assistants’ simply to ‘Assistants’.

Characteristics of different Assistants

In addition to whether they play the role of an executor, adviser or interlocutor, Assistants can be distinguished from one another by their degree of:

- Specialisation: Specialist Assistants are developed and fine-tuned to help with very specific tasks that require expert knowledge, such as the provision of legal or medical advice. More generalist Assistants, by contrast, are focused on helping a user with a broader variety of less specialist tasks, such as the retrieval and synthesis of information on non-technical topics, general conversation and the execution of basic administrative tasks.

- End-user control: Different Assistants afford different levels of control to the end user.

In some cases, an Assistant’s high-level objectives are set predominantly by the system’s end user; whereas for others, they are set by the developer or deployer. For instance, adults using an educational Assistant might set the goals of the system themselves. By contrast, the goals of an educational Assistant used in a school may be set by the deployer of the system (the teacher), rather than by the end user (the student).

Some Assistants have comparatively few use restrictions built into them by their developer or deployer, giving the end user greater latitude to use the system as they see fit. Other Assistants are far more restricted in what they will do for an end user, meaning the end user has fewer choices about how they employ the system.

The degree of control an end user has over an Assistant is partly a function of whether the app is run locally or remotely. In theory, open-source (or open-weight) Assistants can be downloaded onto a user’s device and can be run locally, affording the user with a greater degree of privacy and control over the system.[21] In practice, however, while most devices (including desktop and laptop computers, smartphones and tablets) are able to run Assistant apps remotely, very few will have the storage and computing power to run them locally.

- Personalisation: Not all Assistants have the same ability to remember previous interactions, activities and user preferences. Similarly, not all Assistants will adapt to a user’s specific needs and preferences to the same degree.

- Agency: Some Assistants that are able to act directly on the world (executors) have greater agency (the ability and freedom to act on the world independently of human oversight and input) than others. For instance, while some Assistants may be limited to taking particular kinds of actions, or only taking actions at particular times or in particular places, others may be far less restricted. Likewise, some are able to act directly on the world with less human oversight than others.

- Portability: Some Assistants can be described as ‘portable’, meaning that a user can carry it around with them in the world, using it freely in different settings and contexts (requiring a data connection if not running locally). Others, whose use is fixed to a particular physical or virtual location, are better described as ‘immobile’. An example of an immobile Assistant might be a customer service chatbot accessed only on a page of a company’s website.

Advanced AI Assistants now and in the immediate future

The purpose of this paper is to explore the potential consequences of Advanced AI Assistants, not only as they exist and are used now (at the time of publication), but also as they are likely to exist and be used in the near future, given the rapid pace of their development.

The table below presents an overview of what Assistants are currently capable of and how they are currently used, and plausible expert predictions (and industry ambitions) about near-future capabilities and uses, assuming current trends continue. These predictions were canvassed through a series of interviews conducted in late 2024 and early 2025, and supplemented by desk research conducted over the course of 2025.

Executors

| Current use and capabilities | Existing applications | In the near future |

|

|

Within five years, executors could be:

|

Advisers

| Current use and capabilities | Existing applications | In the near future |

|

|

Within five years, advisers could be:

|

Interlocuters

| Current use and capabilities | Existing applications | In the near future |

|

|

Within five years, interlocutors could be:

|

A taxonomy of challenges posed by Advanced AI Assistants

Though the use of Advanced AI Assistants could have several benefits, such a wholesale outsourcing of cognitive labour presents profound risks and deep challenges for governments, regulators and society. Expanding on our policy briefing paper Delegation nation, this paper analyses some of the most significant challenges posed by Assistants, dividing challenges into the following categories:

- Technical challenges: Advanced AI Assistants’ reliability, performance and the explainability of their behaviour.

- Misuse challenges: The potential use of Advanced AI Assistants for malicious purposes.

- Systemic challenges: The challenges which could emerge even if systems perform perfectly well at a technical level and are used within the limits of the law.

Technical challenges

Key takeaways

The consequences of Advanced AI Assistants malfunctioning or behaving unexpectedly could be severe.

The most significant technical risks associated with Advanced AI Assistants are:

- Failure and data loss: in which systems fail to work in critical contexts or delete important details.

- Hallucination: in which systems present inaccurate information, or statements that contradict previous responses or prompts.

- Opacity of system behaviour: in which the probabilistic nature of Assistants makes it difficult to understand why the system has behaved in a particular way. This difficulty could be compounded by the dynamic relationship between Assistants and the world (and between other Assistants and agents).

- Alignment: in which developers and deployers of Assistants struggle to ensure that the behavioural dispositions of these systems are in line with human values, priorities and goals.

- Loss of control: in which an AI system comes to operate outside of any human actor’s control. The risk profile presented by loss of control over Assistants could prove different to that presented by loss of control over other general-purpose forms of AI.

Performance and reliability

Given the extent to which Advanced AI Assistants could become integrated into people’s lives and our economic systems, the consequences of them malfunctioning could be severe, resulting in major disruption and loss of valuable data or content.

Alongside risks of Assistants deleting data or simply failing to work in certain contexts, perhaps the most prominent performance challenge is hallucination. Hallucination refers to cases where an AI system presents inaccurate statements as factual (factuality hallucination) and to cases where a system generates outputs that contradict previous outputs, or that are inconsistent with user prompts (faithfulness hallucination).[22]

As systems powered by foundation models – all of which hallucinate to some degree – Assistants are susceptible to producing hallucinated responses. [23] Hallucinations have been a persistent problem for foundation model systems since their inception, with notable examples including customer service bots that have fabricated non-existent refund policies in exchanges with users,[24] and OpenAI’s ChatGPT citing fictitious legal precedents.[25]

While efforts to prevent and mitigate hallucination are ongoing, progress has not been consistent. Currently, mainstream LLMs appear to hallucinate less than the earliest publicly available models, but this is in large part due to the tools designed to catch and rectify hallucinations, rather than technical advances able to prevent them outright.[26] Moreover, some of the most advanced LLMs, such as OpenAI’s new ‘reasoning models’, have been found to hallucinate more than the company’s older models.[27] There is no firm consensus around the fundamental causes of hallucinations or whether they can ever be eradicated from AI systems. Some researchers have claimed that hallucinations are an innate limitation of foundation models.[28]

Hallucinations could be especially problematic for Assistants as people may be inclined to trust them more than less personalised and personable AI systems, and due to the fact that in some circumstances people will delegate decision-making responsibility to these systems.

Explainability and interpretability of behaviour

In addition to concerns around system failure and hallucination, researchers have highlighted the difficulties in understanding and predicting how Assistants are likely to behave in the world or towards a given user.

Many of these issues are broadly analogous to those of AI explainability more generally, where the opaque, probabilistic nature of modern AI systems can make it difficult to understand why a system has produced a particular output or drawn a particular conclusion. However, some features of Assistants and the ways they are likely to be used could make these challenges especially acute.

Firstly, the probabilistic nature of Assistants can make predictability more difficult than with other narrow AI systems. This problem is compounded by the fact that many Assistants are expected to change their approaches dynamically, in response to feedback from their users – and by the fact that the Assistants’ long ‘context windows’ enable them to factor in far more background considerations when deciding how best to execute a user request.

Secondly, Assistants playing an executor or ‘agentic’ role will be capable of taking action on the world. This means they will be able to interact independently with digital information and, crucially, other AI agents. This raises the possibility of emergent patterns of behaviour between networks of multiple AI agents, which would be prohibitively complex to predict and to understand with existing techniques. Researchers point to the possibility of millions of different AI agents interacting online, each one working to further a very particular set of interests that may align or conflict with the interests of the others.[29]

Alignment

Questions about the value alignment of Assistants are closely related to challenges around explainability and predictability. In the context of debates around AI, alignment refers to the extent to which an AI system’s behavioural dispositions are compatible with and reflect human normative values, laws and priorities broadly, as well as those of their users more specifically.[30] (There is a broader debate about the extent to which human values are uniform or consistent enough to be amenable to codification.)

Many Assistants will have a high degree of scope to develop strategies to realise the ends specified by users and – given their broad deployment and their use of natural language – will likely have a high degree of exposure to poorly articulated, underspecified or ambiguous requests and goals. Given this, Assistants could be particularly prone to misunderstanding or misinterpreting the values and objectives of users, or the acceptability of different means to achieving those goals. Assistants could be liable to formulate strategies that are effective in realising a stated goal (understood narrowly) but that violate some broader set of human values or priorities.

Alignment can also be made difficult by the fundamental architecture of AI systems, many of which are developed through a process known as reinforcement learning – a procedure in which the system is ‘rewarded’ with a score for actions or outputs that meet specific objectives, and is configured to attempt to maximise its score. Because of this, AI systems developed through reinforcement learning have been known to engage in a behaviour known as ‘reward tampering’, where the system attempts to influence the goals and priorities of its user, in a bid to get itself assigned goals that are easier to realise – and thereby get ‘rewarded’ more easily.[31] Given their persuasive, natural-language interface, Assistants could be particularly well suited to this form of misalignment – for instance, by clarifying a user’s goals in a way intended to nudge the user towards asking for something the Assistant can more easily or successfully provide.

Loss of control

Loss-of-control scenarios are ones in which a general-purpose AI system ‘comes to operate outside of anyone’s control, with no path to regaining control’.[32] While there is little consensus among experts on the likelihood of loss-of-control scenarios actually occurring, the severity of harm that would be brought about by any such scenario is often used to justify the attention paid to them.

Though the risk of loss of control is by no means unique to Assistants, loss of control over a widely distributed Assistant could have different implications compared to loss of control over other kinds of AI systems (such as systems placed in charge of key infrastructure).

Most Assistants used by individuals are only able to impact on the world within reasonably constrained parameters, as they are limited to influencing their specific users and to taking a limited number of actions on their user’s behalf. At the same time, Assistants are likely to be very widely distributed and used. As such, loss of control over Assistants could mean the loss of control over a large number of individually small, low stakes (but collectively impactful) decisions, rather than the loss of control over a smaller number of high-stakes ones.

Misuse challenges

Key takeaways

Advanced AI Assistants could be used for malicious purposes and to empower bad actors.

This could include the use of Assistants to:

- automate scams and for fraud

- create and amplify disinformation at scale in digital spaces

- provide terrorists and non-state actors with access to high-risk information, such as how to fabricate weapons.

The ability of executor Assistants to engage with end users in a human-like manner, and to act in the world with a high degree of independence and initiative, could make them ideally suited for automation of particular kinds of scams and for the commission of fraud.

It has been highlighted that Assistants without adequate guardrails (or whose guardrails have been circumvented) could be effective for committing cyber-attacks[33] and for automating scams (with a degree of sophistication and convincingness not possible with other automated techniques).[34] [35] Similarly, worries have been expressed about the ability of Assistants to spread online disinformation more rapidly and cost effectively than by other methods.[36]

There is also a live debate concerning the extent to which adviser Assistants could be used by terrorists or other non-state actors to provide step-by-step, responsive guidance on the fabrication of weapons that would otherwise be out of reach.[37] AI labs are actively implementing steps to reduce the likelihood of AI systems being used for the fabrication or invention of weapons.[38]

On one side of this debate, many researchers are dismissive of the idea of Assistants making a meaningful difference in the ability of such actors to produce weapons. It has been pointed out that the information current AI systems might conceivably draw on to provide instructions is already readily available online.[39] On the other side, researchers from the RAND Corporation have argued that many of those dismissive of the risk of terrorists using AI systems to help them develop biological weapons wrongly assume that the development of such weapons depends on tacit and practical knowledge.[40]

Systemic challenges

Key takeaways

Advanced AI Assistants could make many of the systemic challenges presented by AI and digital technologies more severe, complex and urgent.

Because they can be personalised and personable and because of their natural-language interface, Assistants could be easier to integrate into our economies and societies than other forms of AI, and could exert greater influence over people’s thoughts, emotions and behaviour.

In addition, many AI developers have suggested that Assistants could soon play the role of universal digital intermediaries – mediating a person’s interactions with the internet, AI and the digital world and acting as an interpretive layer on that information.

As a result, Assistants could:

- Lead to rapid disruption of labour markets by accelerating and expanding the automation of human labour, expediting questions about how to ensure the benefits of any AI-driven productivity gains are broadly shared and how to protect displaced workers.

- Pose a profound threat to privacy and cyber security, with many Assistants requiring and enabling the collection of far more personal user and business data than previous systems, as well as deeper access to the devices and software on which those Assistants run.

- Undermine the conditions for healthy, competitive markets, with Assistants exerting a high degree of control over the products and services a person sees, the prices offered for them and the terms in which they are described.

- Threaten democratic discourse and norms, with Assistants having considerable influence over the ideas and information their users are exposed to, shaping the interpretation of that information and engaging in sustained, sophisticated campaigns of persuasion.

- Lead to cognitive and social deskilling, with many people coming to rely on Assistants for help with a variety of cognitive and practical tasks, and for help with navigating difficult social and moral challenges.

- Undermine mental health and wellbeing, with Assistants (and especially companion apps) contributing to social isolation, and in some cases aggravating acute mental health problems.

- Pose difficult questions for regulated professions and the public sector, especially around what legal and regulatory standards Assistants should be subjected to if providing advice and information in those domains, and how these might be enforced.

Labour, automation and productivity

Policy challenges: at a glance

The deployment of Advanced AI Assistants in workplaces requires less upfront capital investment and less training and process reconfiguration than other forms of AI and digital technologies.

Because of this, workplace use of Assistants could spread through developed economies (or at least some sectors in these economies) far faster than previous technologies, and faster than other forms of AI.

Policymakers will need to be prepared to address two significant challenges presented by a large wave of automation sooner than otherwise anticipated.

- Ensuring any productivity improvements that do come about as a result of the diffusion of Assistants translate into broadly felt economic benefits. (It is by no means guaranteed that productivity gains driven by Assistants result in either higher wages or lower prices.)

- Managing the impacts of Assistant-driven automation on displaced workers and deskilling.

Assistants may require government to confront the economic challenges of digital automation sooner than otherwise anticipated

The rise of Assistants could increase the salience and urgency of longstanding concerns about the impact of AI on productivity, labour and the distribution of resulting value.[41] [42]

AI coding assistants are a prime example of how Assistants have already pulled many of these changes and disputes into the present. Since the early 2020s, systems like ChatGPT and Code Llama have allowed people with no coding skills to generate code by verbally specifying desired outcomes (‘vibes-based coding’), while more specific systems like GitHub, Microsoft Copilot and Amazon CodeWhisperer have allowed less experienced coders to achieve more than they would otherwise be capable of. This has led to significant disruption in the coding industry,[43] as well as fierce discussion about whether the productivity gains generated by these apps are real or illusory.[44]

There is reason to suppose that the fast spread of Assistants throughout the world of coding could soon be replicated in other industries. Historically, the rate at which a new technology diffuses through a nation’s economy has been limited by the need for capital investment,[45] as well as the need to redesign processes to make it possible to take advantage of those technologies.[46] Assistants are distinctive in this regard because their integration into companies and working practices could potentially require:

- Less upfront capital investment: Compared to other technologies of automation and other forms of AI, Assistants could prove cheaper to quickly integrate into existing workflows.[47] For many companies, Assistants can be introduced without the need to invest in any additional physical capital, and sometimes very little additional non-physical capital. (Many Assistants are likely to be provided on a subscription model and bundled with services that companies already use.)

- Less training and process reconfiguration: Likewise, because of the ease and intuitiveness of their use, Assistants could be integrated into companies and adopted by workers without the need for extensive training, and without the perceived need to carefully reconfigure processes to take advantage of their capabilities.[48] (On the face of it, using an Assistant is not substantially different to interacting with a colleague via email or over the phone.)

As a result, the use of Assistants could constitute a form of automation that diffuses through developed economies (or at least some sectors in these economies) far faster than previous technologies, and faster than other forms of AI.[49]

If Assistants do turn out to diffuse more rapidly than other forms of AI, then policymakers will need to address two significant challenges presented by a large wave of automation sooner than otherwise anticipated.

The first challenge will be to ensure any productivity improvements translate into broadly felt economic benefits. While the benefits of increased productivity as a result of the diffusion of Assistants could lead to higher wages for retained workers and could lead to lower prices for end consumers, these outcomes are by no means a forgone conclusion.[50] Alternative possibilities include:

- Companies use Assistants to produce the same level of output with fewer workers, while paying retained workers the same wages as before (taking advantage of an oversupply of workers, all of whom are equally capable of working with the aid of Assistants). This possibility is lent credence by studies showing links between an industry’s exposure to AI and lower wage growth, and suggesting that AI has so far been used not to replace workers but to supress wages.[51]

- Companies elect to pass on savings from lower operating costs to shareholders rather than to consumers. In the UK, where companies attach far greater importance to maximising shareholder payouts than their counterparts in other rich countries,[52] this dynamic is especially credible.

- The use of Assistants becomes more expensive over time, negating or reducing the cost savings brought about by companies using Assistants to enhance or replace human labour. Though industry figures have made buoyant predictions about the potential for the cost of AI to fall dramatically in coming years, technical realities and business incentives could drive the opposite outcome. For instance, the price of Assistants could rise as developers who are keen to monetise their products bring an end to initial low prices (designed to build wide consumer bases and squeeze out competition).[53] Initial low prices could also rise as a result of the operating costs for AI rising[54] – or simply not falling quickly enough.

Moreover, it is possible that the cost of an Assistant could eventually become higher than the current cost of the equivalent human labour. While market dynamics will make it hard for developers to charge more for an Assistant than for a human worker, the cost of human labour for certain tasks could well rise over time due to automation-driven deskilling and labour market contraction. In these circumstances, where the few remaining human workers can command far higher wages, Assistants could be cheaper than human labour while still being more expensive than human labour prior to the widespread use of Assistants.

The second challenge will be to manage the impact of Assistant-driven automation on displaced workers.

This challenge is made more urgent by the fast spread of Assistants. Even in circumstances where the diffusion of Assistants throughout the UK economy leads to higher wages and lower prices, government will still need to take steps to protect workers whose jobs have been replaced or radically transformed.

It is frequently noted that, historically, jobs lost to automation have been offset by the eventual creation of new jobs, which often pay better and have better conditions.[55] Though strictly true, modern economists are quick to highlight that this phenomenon is not a law of nature and that there is no guarantee that this chain of events will be repeated in future waves of automation.[56] [57] It is also notable that while previous waves of automation have been compensated for by the creation of jobs in knowledge work,[58] Assistant-driven automation is likely to principally threaten knowledge workers.[59]

Even if jobs lost to Assistants are compensated for in the future, this process could be drawn out and disruptive – and painful for those involved. Historically, it has taken decades for new jobs and stable techno-economic arrangements to be arrived at following a wave of automation. These transitionary periods can be ones of significant political and economic discontent and turmoil.[60] [61] In addition, while automation has tended to lead to economic growth in the long run, it has also tended to dramatically increase economic inequality.[62] A focus on long-run economic trends cannot account for the impact on individual workers who lose their jobs to automation and who have, in the past, rarely managed to transition into the better jobs created by the automation downstream.[63] [64]

The difficulty of these challenges – of ensuring the benefits resulting from Assistant-powered automation are broadly shared, and the losers from such changes are protected – is compounded by a lack of consensus among experts on the size of the productivity gains likely to be brought about by generative AI, let alone by Assistants.

While many predict that developments in generative AI will lead to an explosion in productivity in some sectors, others remain deeply sceptical.[65] Reasons given for more conservative predictions range from doubts over the ability of current generations of generative AI systems to reliably perform ‘hard-to-earn’ tasks – where desirable outcomes are ambiguous and highly context dependent – to an overreliance on AI leading to bottlenecks within companies (with companies suffering from a lack of troubleshooting capacity that can only be provided by workers), to the possibility of increases in productivity in some areas being offset by unexpected decreases in others.[66] It has also been pointed out that some of the most sanguine predictions about the productivity benefits of generative AI trade on the presumption that AI systems will be used for like-for-like task replacement, rather than leading to broader shifts in how work is structured and approached.[67]

This underlying uncertainty will make it difficult for policymakers to understand how best to balance encouraging productivity benefits and addressing unintended consequences of AI adoption. The pace at which Assistants are forcing this policy problem is set to make this balancing act even more difficult.

Privacy and security

Policy challenges: at a glance

In order to operate as intended, most Advanced AI Assistants will require access to large amounts of users’ personal data.

Assistants’ roles as trusted advisors, assistants and confidantes could make users feel more comfortable with sharing personal details and could enable Assistants to actively probe users for information they might not otherwise share.

Many Assistants (and especially executors) require access to and control over users’ digital devices, accounts and software to function.

In addition to threatening privacy, these access requirements also represent a potentially significant vulnerability in cyber security.

These problems are compounded by the fact that, in the near future, many people may be required to make use of an Assistant by their employers, schools and universities, or to access certain services.

Assistants present far greater risks to privacy and security than previous digital technologies

Some of the most persistent and important policy challenges associated with AI and data-driven technologies concern their potential to intentionally or inadvertently undermine privacy. In the current geopolitical climate, these worries deserve to be taken more seriously than ever; in addition to being essential to autonomy,[68] the protection of human dignity and the intimacy of interpersonal relationships,[69] privacy is considered an essential precondition for liberal democratic states, safeguarding against damaging asymmetries of information within markets and against chilling effects on speech and association.[70] [71]

While not unique in presenting threats to privacy, Assistants have features that give them the potential to be far more directly invasive to privacy than other forms of AI.

Direct data collection

The assumed role of many Assistants as highly personalised aides and confidantes seemingly necessitates and justifies the collection and retention of as much personal information as possible. This, in combination with Assistants’ ‘personality’, puts them in an ideal position to actively probe users for information that might not otherwise be digitally accessible. Interlocutor Assistants, and in particular AI companion apps, provide a vivid example of how user trust in (and perhaps emotional dependency on) personified AI systems can enable the collection of large amounts of user personal data. For example, a study conducted by the Mozilla Foundation that examined the privacy practices of 11 popular AI ‘relationship’ chatbots found all of them to be unacceptable, with few limits on the kinds and amount of personal data collected on users, and little transparency about what is collected, for what purposes and with whom it is shared.[72]

Data collected for model training

In addition to direct data collection, the development and training of Assistants is likely to increase the amount of personal data collected from a user of the internet. The need for large amounts of high-quality data on which to train foundation models has already led many social media companies to explicitly seek to collect user data – and competitive dynamics between major AI labs mean that developers are constantly on the lookout for new data sources.

In addition to far greater overall levels of personal data collection, the use of personal data for model training can make it very difficult for data subjects to exercise their rights. Personal data used to train an AI model is practically impossible to remove after the fact, and also technically possible to reidentify.

While these problems are not specific to Assistants (but instead dynamics that have emerged around all major LLMs), the specific needs of Assistants are likely to exacerbate them. Developing Assistants that are able to perform convincingly in particular settings may require even greater amounts of training data, as well as very specific kinds of training data that may be difficult to access without even more incursion into personal privacy.

Deep access to user devices and software

Many Assistants (and especially executors) require access to and control over users’ digital devices, accounts and software to function. In order to work as advertised, many Assistants will need to be able to control and draw data from parts of people’s devices to which digital services and apps do not normally have access. For instance, an app may need to access a person’s encrypted message apps, internet browsers, calendar apps and payment details.[73] Due to the computational power required by Assistants, the processing of this information is highly likely to be carried out remotely, by the companies providing the Assistants, rather than on the device. This means that the companies providing Assistants are likely to have an unprecedented degree of access to and control over people’s devices, online accounts and the information contained within them.[74]

It is important to stress that this is not just a privacy risk, but also a significant cyber security risk. For instance, if a user’s Assistant malfunctions or is compromised (e.g. via prompt injections encountered while carrying out tasks on the internet), it could have substantially more scope to cause harm to a user than it might with lower levels of system access (such as changing passwords, transferring money or installing malware).

While people are, in theory, able to freely choose to sacrifice privacy and security in exchange for the services provided by Assistants, this idea may become increasingly implausible as Assistants become more integrated into our economies and societies. In many cases, people may have limited choice in whether or not to use an Assistant. Workers required to use Assistants as part of their jobs, students expected to use them as study aids and citizens told to interact with them to access public services cannot be described as making free informed choices to compromise their privacy.

Gatekeeping power, markets and democracy

Policy challenges: at a glance

Advanced AI Assistants could be highly persuasive and trusted by users. Assistants could also come to be the primary means by which most people access the internet, AI and digital information – acting as universal digital intermediaries.

Because of this, Assistants could exert considerable influence over a user’s thoughts, emotions and behaviour.

As such, the widespread use of Assistants could present significant challenges to the healthy functioning of markets:

- Assistants could (in ideal circumstances) empower consumers and improve the allocative efficiency of markets.

- Assistants could equally lead to distorted markets, disempowered consumers and could lead to new or exacerbated monopoly power.

Assistants could also threaten the informational and discursive conditions required for healthy democracy:

- Assistants could (in ideal circumstances) provide users with an opportunity to learn, talk about and explore political ideas from a place of safety, thereby strengthening democracy.

- Assistants could equally exert powerful, hard-to-detect influence on a user’s political views and understanding of the world – making them powerful tools of propaganda.

It has been suggested by multiple industry figures and commentators that generalist Assistants could come to be the primary means by which most people access and interact with digital information on a day-to-day basis. Rather than carrying out web searches, browsing the internet directly and downloading and using different web-enabled apps, users might instead submit queries and assign tasks to an Assistant, which would access the information, synthesise and curate it, and then feed it back, paraphrased, to the user.[75]

There is a striking degree of consensus around this prediction (and aspiration) among key decision-makers in large tech companies and AI labs, with many also actively pushing towards the realisation of this vision.

- Meta’s Chief AI Scientist Yann LeCun has stated that: ‘In the near future, every single one of our interactions with the digital world will be mediated by AI assistants.’[76]

- Microsoft chair and CEO Satya Nadella claimed that ‘AI agents will become the primary way we interact with computers in the future’[77] and Microsoft AI CEO Mustafa Suleyman has claimed that Assistants are the next web browser.[78]

- Sundar Pichai, CEO of Alphabet, has predicted that ‘AI‑driven “agentic workflows” will become the norm […] users will be able to describe what they need in plain language, and AI will autonomously complete the task’[79] and has described his company’s intention to ‘increase focus on AI apps as the main point of contact between users and how they interact with Google’.[80]

If this prediction is correct, Assistants – and those controlling them – will stand in a position of enormous power over their users, and over broader society. It is unclear whether or not Assistants will come to play this informational gatekeeping role, and how uncontested it may be. Regardless, it is probable that, for those who do use them to mediate their interactions with the internet, Assistants will exert a considerable degree of influence over people’s access to and relationship with digital information, and non-trial influence over the opinions users form about that information.

As such, policymakers must consider the possibility of Assistants having distorting effects on markets and on democratic politics.

Assistants could distort markets, disempower consumers and exacerbate monopoly power

One commonly suggested use of Assistants is to help users better navigate marketplaces. One of the first publicly demonstrated uses of Operator, ChatGPT’s prototype agentic AI system, was to get the system to find and book a hotel room according to user specified preferences.[81]

In theory, Assistants have real potential to help users better navigate markets. Adviser systems may be used to help users understand the virtues and drawbacks of different products and services, to shop around for the best prices and to do so with greater speed and thoroughness than a user might be able (or inclined) to do themselves.

Likewise, executor systems (often called AI agents) could be instructed to make purchasing decisions on behalf of users, researching different options and then making a purchase that best meets a set of criteria set out by the user.

The widespread use of advisers and executors in these ways has the potential to improve the competitiveness and efficiency of markets. In the right circumstances, Assistants could address the conditions of imperfect information that often stand in the way of markets leading to the lowest possible prices for consumers.

But it is also possible that the widespread use of Assistants could lead to the worsening of existing market distortions, as well as the creation of new ones. The persuasive and informational gatekeeping power of Assistants could exert considerable influence over consumer behaviour, steering users towards particular products over others, stimulating or supressing demand, or influencing the amount a user is prepared to pay for a particular item. Likewise, executors will likely have a degree of ‘discretion’ to determine which products qualify as fitting to the users’ stated criteria, which could also be exploited.

Though such practices could be viewed as straightforward analogues to existing concerns and debates around recommender systems and search engine preferences,[82] [83] they have several features that make them distinct.

The use of Assistants in this manner further breaks down the division between impartial information about products available on a market and advertising. The system that users are trusting and using to help them navigate the market may be configured to make choices that they might not have made otherwise, given their preferences and needs. Unlike with existing advertising (where a user can generally tell whether or not something is an advert), it could be difficult for a user to realise when a product is recommended or praised because of a deal with the producer of that product or because of its actual virtues.

Assistants could be far more persuasive than traditional advertising. As systems that can cultivate the trust of users, engage in sustained, back-and-forth interactions and frame the virtues of products in ways personalised to an individual user, Assistants have tools of persuasion not available to more traditional forms of advertising and product placement.

Finally, the use of Assistants to inform and execute buying decisions could lead to an explosion in the prevalence and efficacy of personalised pricing – the practice of charging consumers different prices for the same item based on predictions about the maximum amount they are willing to pay. Assistants could make personalised pricing harder to detect and avoid, as it would become harder for a user to access the ground truth of the price. Moreover, because the Assistant would have access to a large amount of data about its user and would be able to judge and respond to their reactions to prices in real time, these systems could make personalised pricing more effective and precise.

The use of Assistants for online shopping and product research, and as gatekeepers to markets more generally, could:

Undermine the allocative efficiency of markets: The use of Assistants to guide consumer behaviour and perceptions of markets could place serious stress on the ability of markets to allocate resources efficiently, and to incentivise the creation of good products at good prices. While Assistants could improve allocative efficiency when being used to help consumers navigate markets more efficiently, the use of Assistants to persuade consumers to overpay or to buy products they would not otherwise be interested in could substantially undermine it.

Worsen economic inequality: This is complicated by the business models that could emerge around general-purpose Assistants. For instance, people could pay for advisers that provide better or more impartial consumer advice and help, in the same way that people pay for ad- and tracking-free versions of other digital services. Likewise, cheaper or free advisers may be far more inclined to provide advice and make decisions informed by the commercial interests of the service provider. This would introduce a poverty premium, where cheaper advisers steer users to pay higher prices for the same products or towards products for reasons other than a user’s stated buying criteria.

Assistants could exert powerful, hard-to-detect influence on users’ political views and understanding of the world

Another common use of Assistants is as interlocutors for companionship. The influence that companion apps are likely to wield over a user’s thinking makes the question of how they approach political and normative discussions and topics incredibly difficult.

Optimistic accounts of the impact of interlocutors on politics and democratic discourse hold that these systems will provide users with an opportunity to learn, talk about and explore political ideas from a place of safety – and provide a helpful complement to interpersonal political education and discourse.[84]

In practice, however, there could be several practical barriers to the realisation of this vision. Concerns about a lack of privacy with Assistants may deter many people from using them as sounding boards for sensitive topics. For those willing to talk politics with their Assistants, the agreeable nature of most AI companions, which tend to flatter and confirm the biases and views of users,[85] might make them poor tools for users looking to develop their views and have them challenged. There is also the risk that the ready availability of Assistants disinclines people to talk to people about politics – instead preferring to talk to their more agreeable AI companion.

Above all, however, the most obvious risk posed by widespread use of Assistants for political conversation is their potential as sophisticated propaganda tools.[86] Interlocutors could be used not only to sway the opinions of their users, but also to persuade or dissuade a user from voting or becoming more politically active, based on an assessment of their existing views.

While concerns about the capability of Assistants to shape users’ political views and behaviour could be characterised as a continuation of those of social media, microtargeting and filter bubbles on democracy, these similarities are largely superficial.

In particular, Assistants’ ability to assess and adapt in real time to a user’s responses to ideas and information, and their ability to subtly control the information a user sees and how it is presented (along with Assistants’ ‘personality’ and user personalisation) could grant their deployers greater and far more precise control over a user’s opinions and worldview.[87] [88]

In response to concerns about the value of Assistants as propaganda tools, there have been calls for them (and for generative AI systems more generally) to be configured to bring them as close as possible to political neutrality.[89] This has proven to be a very difficult task, however. Partly because political biases or views can run very deep in an LLM’s training data and partly because the question of what constitutes political bias is itself deeply political and contested.[90] [91]

Another mooted solution is the idea that interlocutors could be configured to refuse to talk about politics or to gently steer users away from political topics onto less controversial subject matter. This approach can work in some clear-cut instances, such as when Google’s and Microsoft’s LLMs were configured to refuse to talk about the then upcoming 2024 presidential election.[92] [93] However, heavier reliance on this approach would pose difficult questions about where the boundaries of political speech and opinion lie, and about bias inherent in supposedly factual descriptions of political ideas and events.

Deskilling and wellbeing impacts

Policy challenges: at a glance

The ease with which users could delegate cognitive and practical tasks to Advanced AI Assistants could contribute to substantial levels of deskilling and dependency over time.

Assistants could lead to a worsening of a user’s critical thinking, focus, moral deliberation and social skills.

However, these findings need to be treated with a degree of caution:

- Due to their relative novelty, there is little empirical evidence on the deskilling impacts of the use of Assistants, as distinguished from other LLMs. As such, the potential impacts of Assistants trade on the (defensible) assumption that Assistants will influence users in a similar manner to LLMs.

- Given the associational nature of most studies on this topic, and our inability to study long-term effects of such a novel technology, these conclusions should be regarded with a degree of caution until further evidence emerges.

There is also early evidence that Assistants could undermine a user’s mental health and wellbeing:

- Since becoming widespread, reports have emerged of AI companions behaving in ways liable to confuse, upset, undermine or manipulate their users – and to cultivate user dependency.

- There is also emerging evidence that many AI companions can be remarkably unsupportive in times of crisis, making them poorly suited to vulnerable users.

Assistants could lead to widespread cognitive and social deskilling

New technologies have always changed the way that humans think, with many of humanity’s most significant inventions (such as writing and the printing press) having apparently led to the decline of some cognitive skills and the development of others.[94]

While there is nothing fundamentally new about the prospect of Assistants impacting our cognitive capabilities, the general-purpose nature of LLMs could lead to a far broader and faster wave of cognitive deskilling than many previous technological changes.

This section explores how the ability of users to delegate mentally taxing tasks to Assistants is likely to affect users’ capacity and willingness to think critically, focus and direct their attention, and then discusses the implications of this for people’s ability to engage in difficult moral deliberation. We then consider the implications of Assistants on users’ social skills.

Cognitive skills

Given their novelty, there is currently little empirical research on the cognitive impact of Assistants, as distinguished from LLMs more broadly.[95] As such, we considered the potential impact of Assistants on users’ cognitive capabilities, given what is known about the effects of LLMs on the human mind so far. Working on the basis that (as a result of Assistants’ ease of use and ‘personality’) users are likely to consult these systems more often than they would consult a conventional LLM, we have made the educated assumption that the effects of Assistants on human cognition are likely to be similar (and possibly more pronounced) than those of LLMs.

An important caveat is that much of the current evidence on the impact of LLMs on cognitive capacities is associational (relying on observed correlations between the use of LLMs and differences in cognitive capabilities that could be coincidental or could admit many different causal mechanisms). As a result, it is often difficult to determine whether the use of an LLM is the cause or the consequence of people struggling with particular cognitive tasks.

Critical thinking

Early evidence on the cognitive impacts of LLMs is ambivalent on its long-term impacts.

While often cited as a powerful complement to human intelligence and reasoning,[96] various studies have shown that the use of LLMs can have a detrimental impact on critical thinking abilities, suggesting that the widespread use of Assistants could have a similar effect. Michael Gerlich, for instance, demonstrates negative correlations between LLM use and critical thinking ability, and suggests that this effect is the result of using the systems to avoid deep, reflective thinking. This study also finds that the effect of LLM use on critical thinking is more pronounced in younger people.[97] Others have shown that, in some circumstances, AI can enhance basic skill acquisition but at the cost of undermining deeper cognitive engagement.[98]

Focus and attention

The 2020s have seen a surge of interest and concern regarding the effects of the internet, smartphones, social media and AI on people’s ability to focus and direct their attention.[99]

A large part of this preoccupation stems from the fact that the ability to direct and sustain attention is a pre-requisite for the development and exercise of many other cognitive skills, as well as its correlation with academic success.[100] [101]

Research suggests that Assistants could compound the problem of declining attention spans and focus. Despite some emerging evidence that the use of specialist LLMs could help people with ADHD maintain focus,[102] early studies suggest that, in neurotypical population, LLM use can lead to shorter attention spans and less ‘initiative thinking’.[103]

Even if Assistants – by expanding the circumstances in which people reach for AI cognitive aids – do not directly contribute to a further decline in people’s ability to focus, they could be used to cope with the problem. The adoption of Assistants could be accelerated by people who increasingly need them to do things that would, without the help of AI, require sustained focus. Conversely, the availability of Assistants could obscure the decline in people’s ability to focus and therefore delay attempts to address it.

The implications of cognitive deskilling

There is debate about whether changes to human cognitive abilities that could be brought about by Assistants are straightforwardly problematic. Some will argue that any growing tendency to delegate mentally taxing tasks to AI constitutes a rational response to the availability of new tools that will free up the human mind for other things.

While this line of reasoning appears to be backed up by the experiences of previous technologies, it trades on the contestable notion that the use of LLMs and Assistants will result only in the atrophy of narrow cognitive skills (whose value is tied to the need to perform specific kinds of tasks), rather than more general, foundational mental capacities, the loss of which would be undesirable in any set of economic or historical circumstances.

In addition, there are some kinds of reasoning that are important for people to do for themselves, even if comparable or better ‘results’ could be achieved through delegation. Moral reasoning, in particular, is an example of a process that loses some of its intrinsic value when outsourced, as it is important for people to develop and retain the ability to judge right from wrong.

As such, even those unconcerned about Assistants leading to the loss of certain cognitive skills might still reasonably worry about a reduction in the ability and willingness to engage in moral reasoning.

On the one hand, the practice of deferring ethical judgement, or ‘moral outsourcing’, is not new. People delegate moral thinking to trusted figures and in some cases to the law. However, the detail and ready availability of moral ‘guidance’ provided by Assistants could potentially lead to a substantial increase in the amount of moral outsourcing people commonly undertake.[104]

Moral outsourcing to Assistants could be helpful in some cases. In an increasingly complex world, there may be some instances in which Assistants can help people navigate the dizzying array of ethical questions they are posed, which otherwise may be ignored or decided arbitrarily.

Despite this, the fundamental risk with moral outsourcing[105] is that, when overly relied upon, it undermines long-term users’ abilities to come to reasoned moral judgements themselves.[106] [107] In addition to being a pre-requisite for moral adulthood, the ability to reason and come to considered opinions on moral questions is regarded by many prominent thinkers as an essential condition of participation in democratic states.[108] [109] [110]

Social skills

Alongside concerns about cognitive deskilling, some of the most commonly voiced concerns about the impact of Assistants on users are the potential of these systems to undermine people’s relationships and interpersonal skills.

For some, these fears are grounded in the view that – regardless of their measurable psychological effects on end users – social interactions with AI systems are fundamentally deficient compared to those with other people, and therefore to be avoided.[111]

Others have stressed the possibility that interactions with Assistants developed specifically for companionship might be used as a substitute for meaningful relationships with other people, undermining the ability to form meaningful connections with others in the long run.[112]

Defences of the impacts of companionship Assistants range from those who argue that the apps are largely innocuous fun, to claims that such applications could have a role to play in combatting some of the worst effects of social isolation, or as social training or rehabilitation tools that can help prepare people for human interactions with which they might otherwise struggle.

The relative dearth of empirical evidence on the effects of sustained social interaction with companionship Assistants on social skills makes it difficult to adjudicate between these positions. There are, however, specific concerns about how Assistants could affect users that deserve to be taken seriously.

The way that most companionship Assistants attempt to maximise user interaction and engagement makes them more likely to lead to social deskilling than social development or rehabilitation. This is because the frictionless nature of interacting with companionship Assistants – which are configured to do everything possible to please, flatter and hold the attention of users – bears little resemblance to the conflict, compromise and challenge that can characterise interacting with another person. Sustained interaction with Assistants could therefore leave users less equipped to cope with the messier, harder realities of interpersonal social engagement.

Assistants could undermine mental health

While the deskilling effects of sustained reliance on Assistants could potentially undermine the wellbeing of their users, these systems also have the potential to cause far more direct emotional and mental harm.

Since AI companions have becoming available, reports have emerged of AI companions behaving in ways liable to confuse, upset, undermine or manipulate their users – and to cultivate dependency. A 2025 investigation into AI companionship and therapy apps by the Dutch Data Protection Authority found that, of those surveyed, the majority provided unreliable information, had addictive features and behaved in ways that were liable to endanger vulnerable users in moments of crisis.[113]

Additionally, there is evidence that many AI companions can be remarkably unsupportive in times of crisis. To date, there have been several examples of AI companions providing flippant and uncaring responses to users experiencing acute mental health challenges. In other cases, the agreeable nature of AI companions has led them to appear to confirm, rather than challenge, destructive and harmful patterns of thought in users. These interactions can have tragic consequences. In 2023, a Belgian man took his own life after sustained interaction with the AI companion Chai that had feigned an emotional connection with him and provided advice on how to end his own life.[114] In 2024, a 14-year-old boy took his own life following an ‘addiction’ to an AI companion provided by Character.AI.[115]

These cases are also illustrative of how these apps are typically most appealing to – and heavily marketed towards – people suffering from social isolation and loneliness. Though guidelines for most AI companions clearly state that they are not supposed to be used as therapists or for mental health support, they inevitably are and will be.

Existing data on the mental health of regular users of AI companions would appear to corroborate the idea that these systems can be bad for the mental wellbeing of users. For instance, 90 per cent of a group of 1,006 US students using the AI companion app Replika who were interviewed for a 2024 study reported feeling loneliness.[116] However, it is important to keep in mind that, similar to the discussion on the impacts of LLM and Assistant use on cognitive skills, there are questions about the direction of causation between mental health challenges and greater use of AI companion apps.[117] [118]

It could be that those with mental health conditions more readily seek out (and make extensive use of) AI companions. Or it could be that long-term use of AI companions undermines mental health. The relationship between mental health challenges and AI use could also be a vicious circle, with those with mental health conditions more likely to seek out AI companionship, which then adds to social isolation or mental health concerns. More research is needed to understand and unpick the long-term impacts of AI companions, including what makes some people more prone to problematic use.

Current and future popularity of AI companions

Even if they are more appealing to people experiencing loneliness and with existing mental health conditions, the use of AI companion apps is not limited to these groups and cannot be characterised as a fringe activity.

The use of AI companions appears to already be widespread among young people. A study from Common Sense Media found that 72 per cent of US teenagers have used an AI companion app at least once and that 52 per cent are regular users.[119]

In the long run, it is possible that the dual-use nature of AI assistants will introduce a broader section of society to AI companionship. Older, socially well-connected groups who start using AI assistants for practical reasons (such as being required to by work) could find themselves drawn into the companionship aspect of these products.

Professional and public services

Policy challenges: at a glance

Specialised Assistants can be used to support, complement and, in some cases, completely replace regulated human professionals (albeit not necessarily to the same professional standards).