COVID-19 digital contact tracing tracker

A resource for monitoring the development, uptake and efficacy of global attempts to use smartphones and other digital devices for contact tracing.

1 April 2020

As the COVID-19 pandemic spread across the world and governments worked rapidly to respond, the Ada Lovelace Institute examined the technical, ethical, legal and social questions around the use of digital contact tracing apps. As part of this, we kept track of digital contract tracing systems as they emerge around the world.

Now that many of these apps have moved from development to live deployment, we are sharing our tracking publicly. We hope this will provide a useful reference through offering a brief overview of decisions different countries are making in their efforts to contain the COVID-19 virus.

🔍You can find the tracker here (Google Sheet)

Below, we’ve summarised some of the trends we identified in July 2020 while first collating this spreadsheet and the questions we had about these systems going forward.

Centralised or decentralised?

Decentralised digital contact tracing apps, based on Google and Apple’s exposure notification framework API, have become the dominant paradigm across the world.

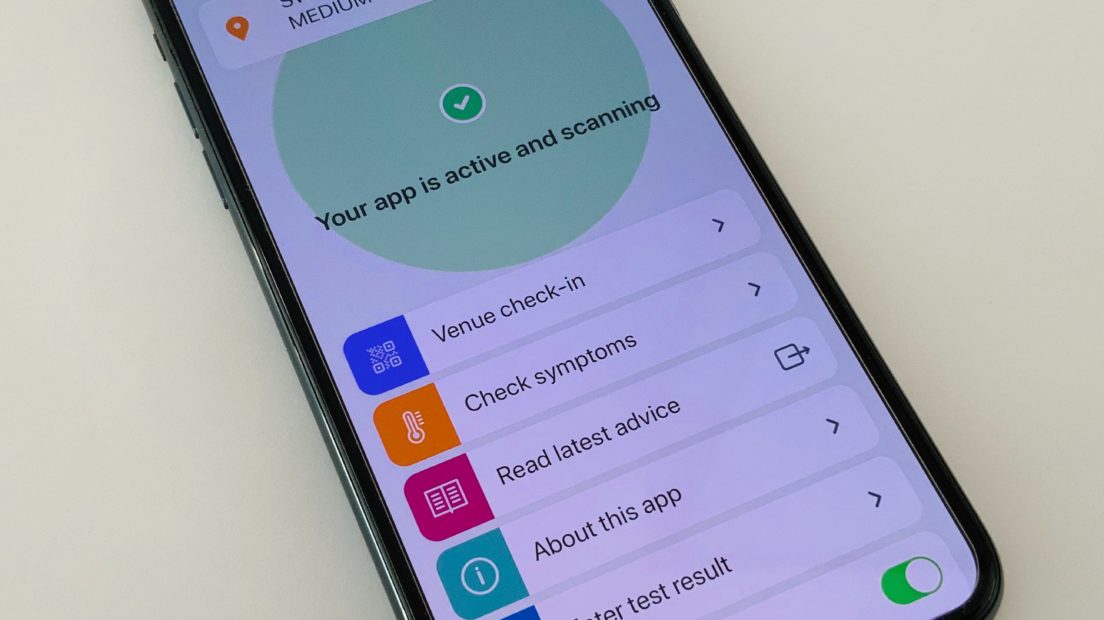

With the UK deciding to drop its in-development centralised contact tracing app in favour a decentralised app using Google and Apple’s framework, France now stands out as the only major European country pursuing its own system. Outside of Europe, new apps from countries like Japan and Canada to Saudi Arabia are using Google and Apple’s framework.

The greatest heterogeneity is in apps that were launched relatively early in the crisis, before Google and Apple released their framework, such as in Singapore, Australia or Iceland, and who have chosen to stick with their original systems.

Legislation

There has been very limited specific legislation on digital contact tracing. Australia and Switzerland have implemented legislation through their parliaments and France has issued a decree. Otherwise, countries by and large appear to have deemed existing data protection regulations and equality and human rights laws to offer sufficient protections for the use of these systems.

Norway does appear to offer a good example of where existing regulation has been enough to intervene when the digital contact tracing app is seen to have overreached. The Norwegian Data Protection Agency has issued a temporary ban on the processing of personal data related to Norway’s Smittelstopp app, after an investigation determined that its collection of citizens’ location data was disproportionate, relying entirely on existing data protection provisions.

Uptake

In almost all countries, with India a notable exception, use of digital contact tracing apps is entirely voluntary. This means governments are relying on citizens choosing to make use of apps in order for them to be effective.

However, even in the countries where uptake is comparatively high, such as Australia, Iceland and Singapore, have plateaued around 40% uptake weeks after launch, with most countries below 20%. Downloads tend to flatten off quickly after the first couple weeks of the application being launched. Without major public information campaigns to drive this up, this appears to be the ceiling for uptake.

Efficacy

So far there is limited empirical evidence available of the efficacy of contact tracing apps. This is unsurprising as many apps have only been running for a few weeks at best and many launched long after the peak of infections in those countries. Whether these apps are effective in practice is thus an open question and one the Ada Lovelace Institute will be continuing to monitor and collate evidence on.

However, there is some evidence emerging from countries that is instructive. One example is Australia’s COVIDSafe app, which was one of apps launched earliest in the crisis. According to their own public health authorities, Australia’s COVIDSafe app has had 6.2m downloads (25% of the total population) but as of 11 June, no local health authorities have announced that COVIDSafe identified any otherwise unidentified contacts.

This case must be caveated with the fact that Australia had a reasonably low infection rate in this period and so could feasibly manually trace every new case. However, it doesn’t tell us how much more quickly cases were identified, which could be an important factor in breaking transmission. Nevertheless, it does raise interesting questions as to how much marginal value apps add over existing methods. As Australia is facing a surge in infections, it may be worth keeping an eye on developments, as an empirical case study in the value of apps in different infection rate scenarios.

Related content

Turn it off and on again: lessons learned from the NHS contact tracing app

The decision to delay the app’s launch is the right one.

The NHS COVID-19 app: is it an enduring public health technology?

Will the long-awaited contract tracing app deliver on its promises for 2020 and beyond?

UK contact tracing apps: the view from Northern Ireland and Scotland

What can we learn about successful approaches to COVID-19 technologies from the devolved nations of the UK?

Why algorithms aren’t the answer: what the public needs to trust technology

A ten-point checklist for the Test and Trace team working on contact tracing app 2.0, based on the findings of rapid online public deliberation.