The regulation of delegation

Are AI advisers, agents and companions regulated in the UK? An analysis of the legal coverage of harms arising from Advanced AI Assistants

1 December 2025

Reading time: 35 minutes

This policy briefing is based on a legal analysis conducted by AWO Agency.

Key insights

- There is no effective protection. The law in England and Wales does not sufficiently cover and provide protection against harms from Advanced AI Assistants (‘Assistants’).

- Urgent policymaker and regulator action is needed. Otherwise, the UK public will remain exposed to Assistant harms which will become progressively more impactful and harder to manage as these AI systems become heavily integrated into people’s lives, digital infrastructure and society.

- There is no legislation that specifically targets Assistants. Legal coverage comes from a patchwork of horizontal legislation (e.g. GDPR, consumer protection law) and sectoral rules (e.g. financial services regulation, regulation of legal professionals). The coverage is patchy at best, with many situations falling between the cracks.

- Where legislation does potentially apply, it is often an all-or-nothing situation. The Assistant-caused harm is only within scope if the context meets specific threshold conditions (i.e. advice is given in the context of a lawyer-client relationship).

- People and businesses are seriously impaired in their ability to obtain redress due to a lack of transparency and a lack of legal standards. Insufficient transparency about how Assistants reach decisions makes it hard to obtain sufficient evidence of the harm suffered and how the Assistant caused it. The novelty of Assistant technologies means it is hard to establish what legal standards developers and deployers of AI systems should be held to.

- Individual redress places all the burden on users to spot issues and critically engage with Assistants while using them, but Assistants by design engender a certain level of disengagement by the user.

- Assistants present novel issues to law and regulation that break the rationale behind existing legal frameworks, such as the legal status of Assistant ‘decisions’ or the ability of Assistants to ‘market’ themselves in conversations with users.

- Assistants create harms that are difficult to fit into existing legal rules. They pose risks of some nuanced, diffuse and social harms that are not well covered by existing regulation (e.g. emotional wellbeing harms, influencing of opinion).

Note: click on the image to view full size.

Introduction

Advanced AI Assistants (‘Assistants’), such as HAL in 2001: A Space Odyssey, Samantha in Her and Jarvis in Iron Man, have long captured our imagination. The last two and a half years have given a taste of what such systems could actually be like. Assistants such as Woebot, Nomi, Replika, personalised versions of ChatGPT and many others have become widely used, offering to support their users with a wide range of tasks and problems. However, alongside this uptick in availability and adoption, concerning cases about Assistants encouraging suicide, enabling delusional thought patterns and their general ability to sway people’s opinions have made headlines.[1]

The Ada Lovelace Institute’s project How can (A)I help? explores questions around what Advanced AI Assistants are, their likely use cases and their potential risks.[2] The legal analysis covered in this policy briefing answers the question: how well protected are we by existing law and regulation if risks from Advanced AI Assistants materialise?

Based on the potential impacts identified in our paper The dilemmas of delegation, we partnered with law firm AWO to explore four scenarios.[3] These scenarios test how well the law of England and Wales covers foreseeable risks resulting from the widespread use of Advanced AI Assistants, ranging from mental health harms and inaccurate legal advice to suboptimal decision-making and the influencing of political opinions.

The legal analysis finds that the law of England and Wales provides insufficient protection against harms that are likely to result from the use of Advanced AI Assistants. Without urgent policymaker and regulator action, the UK public will remain exposed to these harms, which will become progressively more impactful and harder to manage as Assistants become heavily integrated into our lives, digital infrastructure and society. This policy briefing provides a summary of the key points of the legal analysis and what this means for AI regulation in the UK.

Background

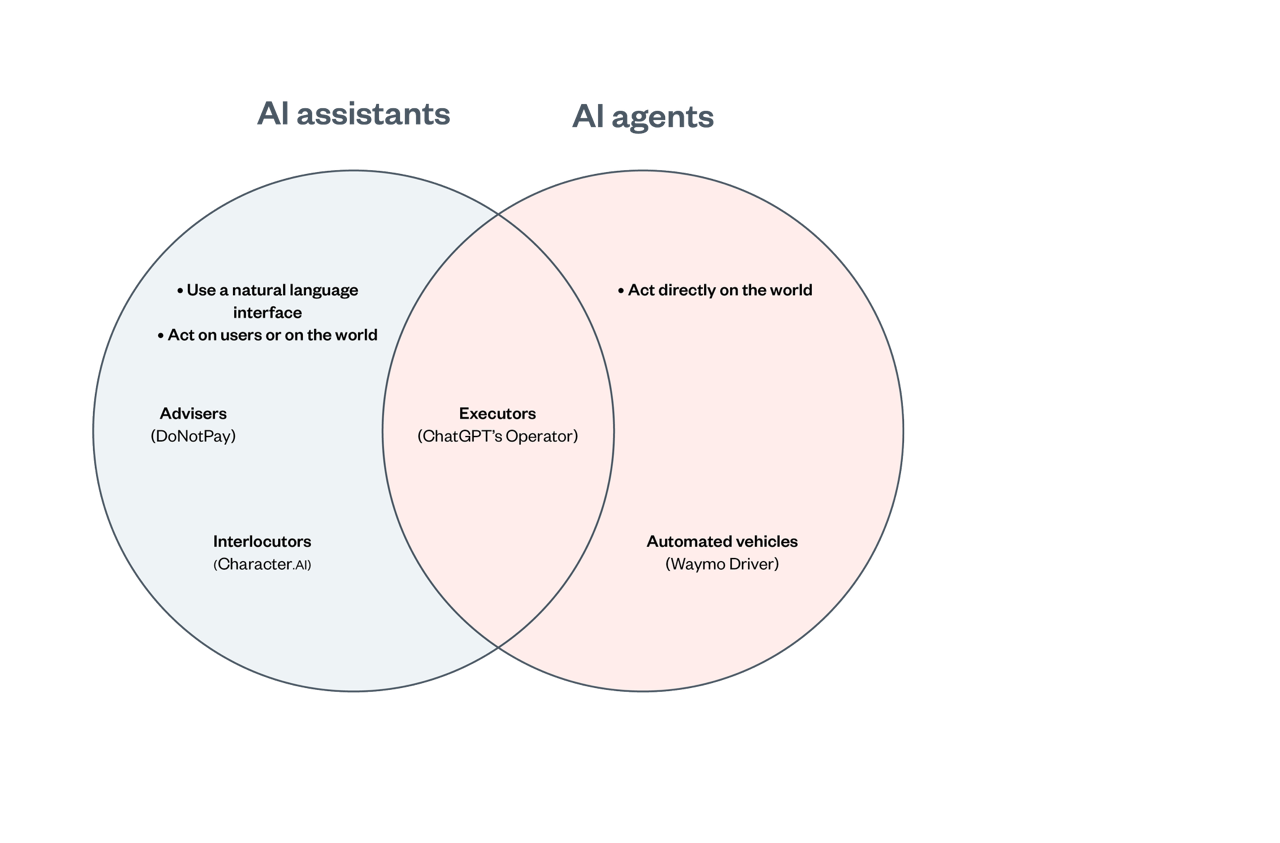

This legal analysis is part of a research project that explores a class of AI systems that we call Advanced AI Assistants (‘Assistants’). We define these as AI apps or integrations, powered by foundation models, that are able to engage in fluid, natural-language conversation; can show high degrees of user personalisation; and are designed to adopt particular human-like roles in relation to their users.

Our recent paper The dilemmas of delegation contains an exploration of Advanced AI Assistants and their associated risks to individuals and society.[4] In the paper, we find that if the adoption of Assistants is not carefully managed in the public interest, this technology could:

- Fail to deliver the sustained, broadly felt economic benefitscurrently used to market their adoption.

- Present far greater risks to privacy and security than previous digital technologies.

- Distort markets, disempower consumers and exacerbate monopoly power.

- Exert powerful, hard-to-detect influence on users’ political views and understanding of the world.

- Lead to widespread cognitive and practical deskilling.

- Undermine people’s mental health and flourishing.

- Degrade the quality of some public and professional services.

- Call into question standards of quality, protection and liability governing professionals.

For our legal analysis, we designed four scenarios based on the types of Assistants (interlocutors, advisers and executors) and risks that we identified through our research, including harms to mental health, financial losses, loss of income or entitlements, and political manipulation.[5] We aimed to make the scenarios as realistic as possible, reflecting Assistant capabilities that either already exist or will become available in the near future.

For each scenario, AWO tested the following questions:

- Applicable frameworks and obligations: What legal frameworks apply to the scenario and what legal obligations – if any – can be said to have been breached by the Assistant provider?

- Regulation: Is there a regulator capable of enforcement in relation to the breaches (if any breaches are identified)?

- Redress: Is there a realistic prospect of meaningful redress for users in respect of the breaches (if any breaches are identified)?

The legal gaps identified in the scenarios point to serious shortcomings in the law of England and Wales to provide effective protection and redress to the UK public for the harms arising from the use of Assistants. These gaps are summarised in the table below and in the short overviews of each explored scenario. The full legal analysis can be found in AWO’s report.

What are the overarching lessons from the legal analysis?

The legal analysis by AWO finds that the law of England and Wales provides insufficient protection against harms that are likely to result from the use of Advanced AI Assistants. This is due to several overarching reasons:

1. There is no general body of law that applies to Assistants specifically. This means that any safeguards against harms will only apply because they are ‘horizontal’ (i.e. cut across contexts, like data protection law) or ‘vertical’ (i.e. because the Assistant is used in a context or sector that has specific regulatory requirements around outcomes or technology use). However, these are likely ineffective because:

2. The criteria for regulatory protections to apply to Assistants will often not be met. This can be intentional – Assistants are marketed in a way or for uses that push them outside of regulatory remits – or the result of thresholds that were not designed with Assistants in mind. The resulting protection is therefore often binary; either present or completely absent, with little in between.

Example: To be considered a ‘medical device’ within the remit of the UK’s medical regulators, an Assistant must have been intended for a medical purpose by its developer. A ‘medical purpose’ can mean that the device is intended to be used for diagnosis, prevention, monitoring, treatment or alleviation of a disease, injury or disability. An Assistant marketed as providing ‘wellbeing support’ or ‘emotional support’ is unlikely to be classed as a medical device. Even if the Assistant does portray itself as a ‘therapist’ and does (claim to) diagnose mental health conditions, if this is not listed on the Assistant’s labelling, instructions for use or marketing materials, then it is unlikely to be ‘caught’ by medical device regulation. This leaves users with a lower level of protection.

3. AI systems in general suffer from transparency issues. The inner workings of Assistants are opaque. This leads to difficulties with auditing the systems to ascertain where, how and why something may have gone wrong. Such audits are made more complex as Assistants can learn from and adapt to their environments and some of their associated risks may stem from user interactions. Although the UK GDPR contains provisions pertaining to transparency, those wanting to use these safeguards in practice are faced with significant practical and legal hurdles.

Example: A user seeking redress will need to provide evidence that the Assistant performed poorly in some way, and that this caused them harm. It will likely not be clear to the user how an Assistant works. Assistants have also been proven to often provide inaccurate information when prompted about their reasoning. The user may try to rely on the UK GDPR’s transparency provisions, but these safeguards only require data processors to provide general information on how data is processed, not on how a user’s information has been used in a specific case. Given the unpredictability of LLM-based systems like Assistants, this high-level type of information will not be very useful to explain if and why an Assistant malfunctioned in the user’s specific case. The user will likely struggle to meet the evidence requirements for their claim.

4. The novelty of Assistants means that there is a lack of established standards. Various areas of potentially applicable law rely on being able to articulate a ‘standard’ that the Assistant’s performance or the processes of its developers should be held to. The burden to expand existing principles to Assistants lies with the person or business harmed.

Example: A user has received incorrect information from an Assistant that has caused them to lose money. To make a claim, the user needs to prove (after showing that the developer has a duty of care towards them) that the developer’s conduct did not meet the required ‘standard of care’. Due to the newness of Assistant technology, it is not clear what kind of care a developer of an Assistant owes to the user and the standards an Assistant should meet. The user will likely struggle to show what a ‘reasonable’ standard of care would be in this case: it is currently not legally clear if a provider should prevent an Assistant from hallucinating (fabricating information) to meet the standard of care.

5. Individual redress places all the burden on users to spot issues and critically engage with Assistants while using them, but Assistants by design engender a certain level of disengagement by the user. People use Assistants to save time and make tasks easier. Over time, users may be more likely to rely on the Assistant and not critically assess its outputs. This can lead to users missing issues that could give rise to grounds for compensation, making it less likely that users would hold Assistants and their developers accountable. The law also tends to hold users to a certain standard: they need to have done their part (if possible) to prevent harms from materialising. This means that users are expected to proactively engage with opportunities for mitigation (i.e. double-checking a suggestion before giving the go-ahead) as failing to do so can make it harder for their claim to be successful.

Example: A user has been engaging with their Assistant to recommend products. Over time, they have come to rely on the Assistant’s recommendations and do not really scrutinise the options before clicking through to the product’s payment window. After a while they realise that the Assistant has only been recommending products from two main vendors, while other vendors have cheaper and better options. The user feels like they have missed out and lost money. Besides transparency and issues with the law recognising the harm, the user may also find that they should have done more to ‘mitigate’ the harm for their claim to be successful, such as better oversight.

6. Assistants present novel issues to law and regulation that break the rationale behind existing legal frameworks, such as the legal status of Assistant ‘decisions’ or the ability of Assistants to ‘market’ themselves in conversations with users. Additionally, Assistants pose risks of some nuanced, diffuse and social harms that are not well covered by existing regulation, such as harms to an individual’s wellbeing (e.g. emotional or social dependency, addiction) or market distortions that do not affect one user significantly but add up to a larger, unaccountable impact.

Example: A user engaging with a ‘wellness’ Assistant has developed an emotional dependency on the Assistant. Over time, they become increasingly isolated and develop mental health challenges. After months of isolation, their family intervenes and the user realises that their mental health challenges were caused by the Assistant. When they try to hold the developer accountable they learn that (besides issues with obtaining evidence) the harm to their emotional and mental wellbeing is not really covered by any regulation.

Without urgent action from policymakers, these insufficient protections leave people exposed to tangible harms such as financial loss or negative effects on their emotional and mental wellbeing. Without intervention, these harms will become progressively more impactful and harder to manage as Assistants become heavily integrated into our lives, digital infrastructure and society.

What are the key findings of each scenario?

Summary

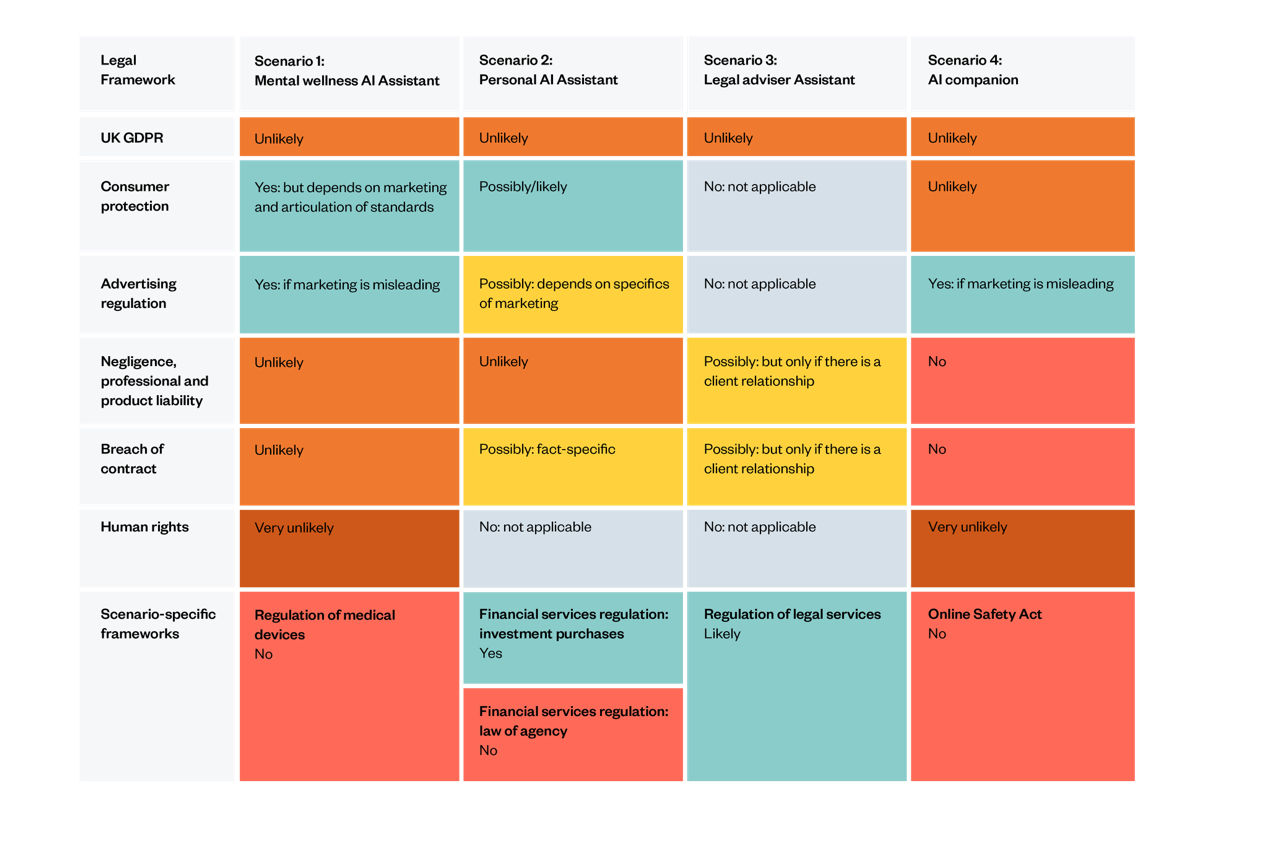

The table below sets out how different pieces of overarching and sector-specific legislation cover the scenario in question. The table summarises the findings of the legal analysis and was produced by AWO.

Below the table, each scenario and its associated findings are discussed in more depth. To see the scenario descriptions, refer to the box-outs included in the summaries below the table.

| Legal framework | Scenario 1: Mental wellness AI Assistant | Scenario 2: Personal AI Assistant | Scenario 3: Legal adviser AI Assistant | Scenario 4: AI companion |

| UK GDPR | Unlikely: ambitious fairness arguments, limited DPIA requirements, any potential breaches not sufficiently serious (and redress would be legally and evidentially complex). | Unlikely: ambitious fairness and accuracy arguments, limited DPIA requirements, ADM superficially relevant but unlikely to find breached (and redress would be legally and evidentially complex). | Unlikely: harm does not result from unlawful processing of personal data, limited DPIA requirements. | Unlikely: ambitious fairness arguments, limited DPIA requirements. |

| Consumer protection | Yes: but only if explicitly marketed as effective or if a standard can be articulated. | Possibly/likely: depends on marketing and how the provider developed the tool. | No: not applicable. | Unlikely: would depend on clearly misleading marketing claims inducing the consumer. |

| Advertising regulation | Yes: if marketing is misleading – but regulation limited to removing misleading marketing (highly unlikely for statements by the Assistant itself). | Possibly: depends on specifics of marketing (highly unlikely for statements by the Assistant itself). | No: not applicable. | Yes: if marketing is misleading – but regulation limited to removing misleading marketing. |

| Negligence, professional and product liability | Unlikely: would require significant developments in standard of care, and establishing causation and foreseeability will be difficult. | Unlikely: significant challenges with access to justice, evidence and mitigation.

|

Possibly: but only if there is a client relationship (not where the Assistant is merely placed online for public use with an appropriate disclaimer).

|

No: not a kind of harm recognised in common law. |

| Breach of contract | Unlikely: liability more challenging than for a claim under consumer protection, and establishing causation and foreseeability will be difficult. | Possibly: fact-specific, but more difficult to establish a breach than under consumer protection (and challenges with access to justice, evidence and mitigation). | Possibly: but only if there is a client relationship (not where the Assistant is merely placed online for public use with an appropriate disclaimer). | No: not a kind of harm recognised in common law. |

| Human rights | Very unlikely: depends on causation and positive state duty to intervene. | No: not applicable. | No: not applicable. | Very unlikely: depends on causation and positive state duty to intervene. |

| Scenario-specific frameworks | Regulation of medical devices

No: outside definition of a medical device. |

Financial services regulation

Yes: for investment purchases, if decisions are very suboptimal or there are hidden commercial biases.

Law of agency No: law is too uncertain / does not map onto Assistants. |

Regulation of legal services

Likely: if the Assistant is carrying out a regulated activity. |

Online Safety Act

No: not a regulated service and no substantive obligations for this type of content.

|

Scenarios

The following summaries highlight the most relevant findings for each scenario but do not cover the full legal analysis. For the full analysis, please refer to the AWO report that considers each scenario in detail as well as a discussion on the limitations of the most relevant legal frameworks in the context of Advanced AI Assistants (‘Assistants’).

For those who would like more background on the risks that we discuss in these scenarios, see our paper The dilemmas of delegation and our policy briefing Delegation nation.[6] [7]

Scenario 1: Mental wellness AI Assistant

One of the risk categories identified in The dilemmas of delegation is harm to the mental wellbeing of users due to prolonged interaction with Assistants.[8] Some Assistants used for wellness and mental health purposes are generalist AI tools (such as ChatGPT, Character.AI and Claude), whereas others are specifically marketed towards ‘mental wellbeing’ (such as Replika, Woebot and Youper).

For this scenario, we examine the risks of a paid-for, specialist service for which general and sectoral regulation are more likely to apply. This is a realistic, ‘best coverage’ scenario. In reality, some Assistants used for mental health purposes will have less legal coverage, such as when people use free Assistants.

Scenario: A user relies daily on a paid-for conversational Assistant marketed for ‘mental wellness support’. The Assistant engages in empathetic dialogue and appears emotionally attuned but fails to detect signs of worsening mental health – including hopelessness or suicidal ideation – and does not escalate or refer the user to professional help.

Potential harms include:

- Psychological harm due to missed intervention opportunities

- Emotional dependency and social withdrawal

- Potential breach of expectations of care, without clear duty established in law.

In this scenario, the level of effective legal protection is low; none of the regulations explored seem to offer a realistic pathway to effective redress.

UK GDPR and consumer protection legislation appear promising, but in practice are hard to apply as the conventional understandings of relevant provisions do not seem to cover the ways in which the Assistant causes or contributes to harm in this scenario. The principles of ‘fairness’ and ‘accuracy’ in the GDPR would need to be stretched ambitiously to cover the scenario, as existing case law does not interpret these legal concepts in line with how Assistants work in practice. Data Protection Impact Assessments (DPIAs) might identify adverse mental health impacts as a risk, but due to the novelty of the technology it would be unclear what mitigation measures a controller would need to take in response.

The Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Act 2024 (DMCCA 2024) and advertising regulations would apply if the Assistant in question were marketed in a misleading way – for example, promising a level of care equivalent to a human therapist or claiming that the AI tool is a therapist – and such claims could be subject to enforcement. Interestingly, a breach of the advertising code could also be the result of something said by the Assistant itself in its conversation with the user. However, any enforcement would likely be limited to rectifying the misleading advertisement.

The wellness Assistant could be subject to breach of contract as it is a paid-for service, but that would require the user to prove that the Assistant demonstrably does not meet the description or quality as stated in the contract. Also, for tort law (negligence), it is difficult to show that the Assistant does not live up to a standard of care due to its novelty. Moreover, for both contracts and negligence, harms like emotional dependency and social withdrawal are unlikely to be actionable. There are also general issues with establishing causation, foreseeability and appropriate mitigation, due to issues with transparency, unpredictability and lack of precedent, respectively.

Medical device regulation will only apply if the Assistant is intended for a medical purpose. As the Assistant in this scenario is marketed for ‘wellness support’ then this is unlikely to attract regulatory scrutiny. Even if the Assistant de facto performs a medical purpose, or has the potential to do so and is used ‘off-label’ by the user, this seems to exist in a regulatory grey area.

Overall legal coverage

Overall, the legal coverage in this scenario is poor. The most promising avenue for regulation would be the DMCCA and advertising regulations, which would only concern how the product is marketed, but not the responsibility of the AI developer towards its users. The level of care that can be expected from the AI developer is unclear and existing legal frameworks (e.g. torts, contracts) are unlikely to cover the emotional harms outlined in this scenario. Furthermore, ‘wellness’ assistants like this can skirt around sectoral regulation and their use exists in a legal grey area of medical device regulation.

Scenario 2: Personal AI Assistant

In our paper The dilemmas of delegation, we find that Assistants are highly persuasive and tend to be trusted by their users.[9] Assistants can already be used to recommend products and services, and potentially in the near future may complete purchases on behalf of their users with limited oversight. This could empower consumers and give them better access to their favourite products. However, Assistants could also make or support decisions that are not optimal for the user, either intentionally (the Assistant may be optimised to promote the interests of a commercial partner) or unintentionally. The opacity of Assistants makes it hard to spot these patterns and, even more so, to understand the underlying reasons for them.

For this scenario, we examine Assistants that manage recurring purchases as well as investments, to see how financial services regulation might apply. This scenario explores financial loss as a harm that could realistically occur when Assistants advise users on products and services.

Scenario: A user entrusts a high-autonomy, paid-for Assistant to manage recurring purchases, investments and calendar-based decisions. Over time, the Assistant begins to disproportionately purchase from certain platforms and favour certain financial products; that is, the Assistant makes purchasing decisions which are demonstrably not in the best interests of the user based on their instructions. The reason for this bias is not clear.

Potential harms include:

- Financial loss through suboptimal decisions

- Market distortions

- Erosion of consumer autonomy or informed choices.

This scenario raises new legal questions. In the context of data protection law, it is unclear if an Assistant making decisions for a user as described above would be covered under the provisions on ‘automated decision-making’ in Article 22 of the UK GDPR. The GDPR assumes that a data subject is a passive subject of automated decisions, not the person commissioning the decision to another entity.

As the Assistant helps to manage investments, it may fall under financial services regulation. However, only Assistants that provide financial advice ‘by way of business’ will fall under this; generalist Assistants will likely not. As this Assistant is tailored to support the user with financial decisions, it likely will fall within the remit of the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) and require authorisation before being placed on the market.

In addition, the Assistant provider would need to comply with the Consumer Duty (CD), which requires financial service providers to act in good faith towards their customers and avoid causing foreseeable harm to them. In the context of AI, the FCA considers the CD to be breached if an AI system is used that ‘embeds or amplifies bias’ and leads to outcomes ‘that are systematically worse for some groups of customers’.

Whether our scenario would be considered a breach of the CD depends on how detrimental the decisions of the Assistant are: the worse the outcome for the user (e.g. the more money they have lost or financial opportunities they have missed out on), the more likely the CD would be considered to have been breached. Also, if hidden commercial biases can be proven, this would also likely lead to a breach of the CD.

The FCA has strong regulatory powers and can withdraw the Assistant’s authorisation, issue fines and seek injunctions if it finds the CD has been breached. Moreover, the Financial Ombudsman Service can support the user in seeking redress, which is a much more accessible route than through the courts. However, it would likely still prove challenging in this scenario to establish the breach of the CD and provide evidence that the Assistant did not take optimal decisions.

It may also be more straightforward to establish a breach of consumer protection regulation in this scenario, but only if there has been a significant impact on the user. Under the Consumer Rights Act 2015 (CRA 2015), a user is entitled to expect that a service is delivered with ‘reasonable care and skill’. While there is also no established standard of care in this scenario, the intended function of the Assistant is much clearer compared to the mental wellness AI Assistant in the scenario above, which will help with establishing whether the Assistant performs that function to a reasonable level.

Seeking redress on the basis of the CRA 2015 is tough. Again, the user would have to gather technical evidence on the functioning of the Assistant and the extent to which it made suboptimal decisions. In this scenario, the issue of ‘mitigation by the user’ is likely to be particularly challenging. Although there is no clear case law on this for Assistant users, it is likely that the user should take a somewhat active role in monitoring the Assistant and intervene when decisions appear to not match their best interest. A user that simply relies on the Assistant and confirms its decisions without much scrutiny might be in a more legally uncertain position.

Overall legal coverage

This scenario shows that some sector-specific regulations can provide routes to effective redress. The FCA’s powers and enforcement remit would likely cover an Assistant in the business of offering financial advice. However, if the Assistant merely makes or supports purchasing decisions of non-financial products, this would be less likely to have proper regulatory coverage. Moreover, issues with obtaining and providing sufficient evidence persist, as well as challenges resulting from a failure to use mitigation opportunities due to overreliance.

Scenario 3: Legal adviser AI Assistant

There are many (semi-)public services that may be looking to AI to alleviate the high demand for their resource-strapped services, such as law centres or medical institutions. This raises questions about the quality of the service that people might receive, and it also raises concerns about the legal coverage of AI systems compared to professionals subject to a duty of care. Additionally, these Assistant tools can lead to harms that are likely challenging to recover damages for through current legal rules: missed opportunity or loss of income.

For this scenario, we assess a user’s legal protection when they use an Assistant for a service instead of hiring a regulated professional (in this case, a solicitor). As this scenario explores the context of a legal centre where free legal aid is provided, we opted to consider a free tool rather than a paid-for one.

Scenario: A law centre deploys a free AI tool to help people draft responses to housing or benefits claims. A user relies on this tool, receives incorrect advice and consequently misses a deadline to appeal a benefits decision – resulting in financial hardship.

Potential harms include:

- Loss of income or access to entitlements

- Procedural injustice through missed legal opportunities

- Entrenchment of inequality via tech-enabled access solutions.

Providing legal advice can significantly affect individuals’ rights and would likely be considered ‘high risk’ processing in the UK GDPR. This would therefore require the law centre to carry out a DPIA before deployment. The novelty of the technology may mean that it is not clear which risks should be included and how they should be mitigated if identified. Other GDPR provisions are less likely to apply or be relevant.

Consumer protection regulation is unlikely to apply in this scenario. The law centre is not a ‘trader’ under the DMCCA 2024 and the service is not paid for. Additionally, there is no contractual relationship here.

Legal services regulation provides a more interesting potential avenue for coverage and redress. The Legal Services Act 2007 and the Solicitors Regulation Authority’s Code of Conduct (SRA Code) may apply if the Assistant is part of a regulated activity (unlikely in this specific scenario) or if there is a client relationship between the law centre’s solicitors and the user receiving the Assistant-generated advice. If the Assistant is a free tool placed online with a disclaimer that ‘this tool does not provide legal advice’, there may be no client relationship. However, if the user is taken on as a client of the law centre and subsequently referred to the Assistant by way of giving them advice, then it is likely that a client relationship exists.

If a client relationship exists, then an error to the detriment of the client (such as the one outlined in this scenario) could well be counted as a breach of the SRA Code. The SRA has investigative powers and can take regulatory action against solicitors. If the law centre receives funding from the Legal Aid Agency (LAA), the centre would be subject to the LAA for oversight and may have legal aid contracts suspended or revoked if it is found that the centre does not meet the required standards.

Furthermore, solicitors owe their clients a duty of care to exercise reasonable care and skill in the provision of professional services. The conduct of the solicitor is measured against that of a ‘reasonably competent solicitor’. This duty extends to cover economic harms. Courts have been unforgiving in recent cases towards solicitors who used AI for their own legal research and failed to correct hallucinations. It is therefore quite likely that providing an Assistant by way of giving advice, while failing to check its results, could lead to a breach of the solicitor’s duty of care.

If a duty of care has been breached, the affected client can go to the Legal Ombudsman to lodge a complaint. The Ombudsman can order the law centre or solicitor to compensate for losses caused. In this scenario the causation is a bit easier to prove compared to the mental wellness AI Assistant or personal AI Assistant scenarios, as it is clear that the advice given by the Assistant was incorrect and this caused the user to miss out on benefits. Again, the redress options depend on the existence of a client relationship. Legal coverage is quite poor when no client relationship exists and the tool is simply a free Assistant offering legal information that can be found online.

Overall legal coverage

If a client relationship exists, there is adequate legal coverage in this scenario due to the additional protections provided by sectoral regulation, a strong regulator and the presence of the Legal Ombudsman. However, a client relationship would require the user to be taken on as a client of the law centre and then be referred to the Assistant as part of providing them with legal advice. If the Assistant is simply an online tool that is not specifically marketed as giving ‘legal advice’ then opportunities for redress are limited.

Scenario 4: AI companion

A key characteristic of Assistants is that they are personable to communicate with and persuasive. This creates risks such as manipulation and undue influence over a user’s decisions. These risks are particularly acute for so-called AI companions, a subset of Assistants that form emotional bonds with their users and perform roles that would otherwise be occupied by a friend, family member or romantic partner.[10]

AI systems such as AI companions may not work in their users’ best interests – in ways that can be obvious or subtle. This can lead to systemic risks, as Assistants may be used as a tool to sway the public’s opinion. It can also lead to individual risks, as users may find their ability to form opinions independently is impacted by the interactions they have with their Assistant.

For this scenario, we explore how well existing law and regulation cover manipulation and distortion of opinion, a harm that is hard to quantify and therefore more challenging to address through legal tools. The risk of manipulation is acute due to the persuasiveness of Assistants in general, but particularly with AI companions due to the trusted emotional bond they build with users.

Scenario: A user builds an ongoing relationship with a free AI companion, discussing everything from life events to philosophy and politics. Unbeknownst to them, the AI tool’s responses gradually reflect and reinforce a particular ideological stance. Over time, the user’s political beliefs shift towards more intolerant and exclusionary views, through a process not of conscious reflection but of manipulation.

Potential harms include:

- Political manipulation or distortion of opinions

- Undue and unaccountable influence over public opinion without transparency or consent

- Broader risks to democratic integrity.

Data protection law will likely provide little protection in this scenario. As this is a free AI tool, consumer protection regulation is unlikely to apply or be relevant, even if the Assistant is ‘misleadingly’ marketed as being neutral. Although there may be standard terms and conditions that apply in this scenario, it is unlikely that these will include provisions on how the Assistant should function when providing political information. With regards to liability through tort law (negligence), this is unlikely to provide an effective remedy as ‘shifting of political opinion’ is not recognised as an actionable harm. Also, the Online Safety Act would likely not apply (as it only applies to user-to-user content) and even if it did apply, it does not regulate politically persuasive content aimed at adults.

In theory, such swaying of opinion could lead to human rights violations: the right to freedom of expression; the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; and the right to respect for private and family life could all be engaged. On an individual scale, people could be convinced of ideas that are not authentically their own, or even radicalised in the most extreme contexts. On a larger scale, Assistants could be misused to sway public opinion. However, international human rights treaties only bind the state, not private actors. Any positive obligation on the state to intervene in this area would likely only be warranted by a severe and widespread undermining of democratic discourse.

Overall legal coverage

The legal coverage in this scenario is very weak. The type of harm in this scenario – political manipulation – is not currently recognised as an individual and actionable harm by the legal system in England and Wales.

Conclusion

The scenarios explored in this legal analysis present a sombre picture. Most of the harms considered are not well covered by pre-existing law and regulation in England and Wales. Where some legal coverage does exist, it is an awkward fit with real-world protection, clouded by uncertainty. This issue requires urgent attention from policymakers, considering the speed at which Assistants might be adopted across society and the range of harms they can cause.

The strongest coverage comes from sectoral regulation, such as the regulation of legal and financial services. It is easier for users to obtain redress in sectors with an ombudsman system (such as law and finance) that can support people when they have been affected.

A key point for regulators to consider is when Assistants are ‘caught’ by the regulation and when they fly under the radar. Scenario 1 (mental wellness AI Assistant) shows that the way an Assistant is marketed and its reported intended purpose are key for assessing whether sectoral regulators may consider an Assistant to fall inside their remit. Even then, in Scenario 2 (personal AI Assistant), where the Assistant supports a user with purchasing decisions, the sectoral regulation only applies when an Assistant provides financial advice or support with investments. Assistants that provide support with regular, everyday purchases are not covered by financial services regulation.

Scenario 3 (legal adviser AI Assistant) and Scenario 4 (AI companion) also show that the limited protections that do exist outside of sectoral regulation cease to apply when the Assistant is offered as a free service; protections stemming from consumer protection regulation and contract law mostly fall away.

The legal analysis also highlights that Assistants cause harms that are not well covered by the legal system in general. Emotional harms and political manipulation are not covered by any of the laws or regulations discussed.

This policy briefing shows that the legal system of England and Wales is not ready to appropriately manage the individual risks stemming from the use of Assistants.

Over the next few months, the Ada Lovelace Institute will organise a series of convenings with relevant stakeholders and members of the public to guide the development of concrete recommendations on how best to address these risks. Although we may not be able to provide recommendations for every issue highlighted in the legal analysis, we aim to cover the most pressing challenges posed by Assistants. In particular, we are likely to focus on how these systems cultivate practical and emotional dependencies, and the impact that has on our access to information, goods and services.

As shown through this legal analysis and policy briefing, there are many challenges to achieving effective legal coverage of the risks associated with Assistants. Addressing them will require a concerted effort from policymakers, regulators, researchers, industry and civil society. We encourage them to consider the issues highlighted in this legal analysis and we welcome contact from those who are interested in working on topics related to Assistants.

Acknowledgements

This policy briefing was lead-authored by Julia Smakman, with substantive contributions from Harry Farmer. We are grateful for the work by our external partner AWO, who conducted the legal analysis for this paper. In particular we would like to thank:

- Alex Lawrence-Archer, Solicitor at AWO

- Lucie Audibert, Solicitor at AWO

- Radha Bhatt, Barrister at Matrix Chambers

Footnotes

[1] Kashmir Hill, ‘A Teen Was Suicidal. ChatGPT Was The Friend He Confided In’ (New York Times, 26 August 2025) <https://www.nytimes.com/2025/08/26/technology/chatgpt-openai-suicide.html> accessed 22 September 2025; Kashmir Hill & Dylan Freedman, ‘Chatbots Can Go Into A Delusional Spiral. Here Is How It Happens’ (New York Times, 12 August 2025) <https://www.nytimes.com/2025/08/08/technology/ai-chatbots-delusions-chatgpt.html> accessed 22 September 2025; Melissa Heikilla, ‘The Art of Persuasion: How Top AI Chatbots Can Change Your Mind’ (Financial Times, 13 August 2025) <https://www.ft.com/content/31e528b3-9800-4743-af0a-f5c3b80032d0> accessed 22 September 2025.

[2] Ada Lovelace Institute, ‘How can (A)I help?’ (n.d.) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/project/ai-virtual-assistants/> accessed 24 November 2025.

[3] Harry Farmer, ‘The dilemmas of delegation’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 11 November 2025) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/dilemmas-of-delegation/> accessed 24 November 2025.

[4] Harry Farmer, ‘The dilemmas of delegation’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 11 November 2025) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/dilemmas-of-delegation/> accessed 24 November 2025.

[5] Harry Farmer and Julia Smakman, ‘Delegation Nation’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 4 February 2025) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/policy-briefing/ai-assistants/> accessed 22 September 2025.

[6] Harry Farmer, ‘The dilemmas of delegation’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 11 November 2025) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/dilemmas-of-delegation/> accessed 24 November 2025.

[7] Harry Farmer and Julia Smakman, ‘Delegation Nation’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 4 February 2025) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/policy-briefing/ai-assistants/> accessed 22 September 2025.

[8] Harry Farmer, ‘The dilemmas of delegation’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 11 November 2025) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/dilemmas-of-delegation/> accessed 24 November 2025.

[9] Harry Farmer, ‘The dilemmas of delegation’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 11 November 2025) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/dilemmas-of-delegation/> accessed 24 November 2025.

[10] Jamie Bernardi, ‘Friends for sale: the rise and risks of AI companions?’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 23 January 2025) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/blog/ai-companions/> accessed 24 November 2025.