Licence to build

Public attitudes to public sector AI

24 June 2025

Reading time: 59 minutes

Key insights

This briefing aims to support those considering the deployment of AI to move in step with the public. We summarise common findings from our research with the public on their views and expectations of AI in the public sector. These lessons arise from engagement with nearly 16,000 people in four nationwide attitudinal surveys and 400 people in deeper qualitative studies.

- There is no single view of AI: public perceptions are nuanced and context-dependent.

People assess tools in context and can identify the benefits, opportunities, risks and harms of individual AI use cases. - Experiences and demographics shape people’s expectations.

People’s understanding, trust and comfort with AI are affected by their personal characteristics, as well as their direct and indirect experiences of technology and the institutions using it. These experiences can exacerbate concerns about AI’s impact on existing inequalities. - Private profits, public doubts: there are concerns about the power and profits of technology companies in public services.

This intersects with concerns around transparency, regulatory powers and access to data. - Support is conditional: the public want evidence, explainability and involvement.

The public value explainability above accuracy when it comes to AI tools, and they expect clear evidence on efficacy and impacts to justify use. There is a desire for those affected to have meaningful involvement in shaping decisions about public sector AI. - Strong governance is a prerequisite for trust.

The public increasingly ask for stronger governance of AI, along with clear appeals and redress processes if something goes wrong. The public are not convinced existing regulations are adequate to ensure that public sector AI works for everyone, supports public good and prioritises people over profit. - Social impact matters: the public oppose uses of AI that could create a ‘two-tier society’.

Discrimination and bias are important concerns, especially in essential services, and people expect AI in the public sector to accommodate pluralism and diversity.

Introduction

In response to an overstretched and struggling public sector, policymakers in the UK are raising expectations about the potential role that AI might play in the delivery of public services. Government departments and local authorities are considering how AI tools and systems might enable innovation and improve efficiency.

To support those adopting AI into public services, we published Learn fast and build things, a synthesis of our research from the last six years on the use of data and AI across the public sector, along with our ‘lessons for success’.[1] One of our key lessons was that successful use of AI requires public licence, and that moving out of step with public comfort can undermine the ability for the public sector to effectively use AI.

This briefing aims to support policymakers and practitioners to understand public views on AI to ensure these tools work for the sector and the public they seek to serve. For this, we have reviewed our research from the last six years on public attitudes towards the use of data and AI in public services. During this period, we have engaged with nearly 16,000 people through four nationwide attitudinal surveys, and nearly 400 people in deeper qualitative studies, to understand more about public views on data and AI.

Alongside crosscutting findings relevant to the public sector – such as public views on regulation – this briefing explores how people think about data and AI in an array of contexts and uses, including policing, healthcare, education and social work. It includes people’s views towards functions and operations that public sector professionals are likely to be considering when it comes to the use of AI, such as decision-making, risk assessment, surveillance and customer service. The briefing is organised around six findings, which identify themes that have reoccurred across different use cases, populations and methodologies.

Why does public licence matter?

Before delving into the evidence, it is important to understand why public licence is a prerequisite for the successful adoption of AI in the public sector.

Public services are held to a high standard due to their impact on people’s lives, from deciding who is eligible for expensive drug treatments to putting children into foster care. In many parts of the public sector, the importance of these decisions is compounded by the sector’s role as the sole provider of a service – there are no alternative provisions for citizens dissatisfied with the welfare state or the justice system. The first of the Nolan Principles (the Seven Principles of Public Life) is to ‘act solely in the public interest’.[2] As Peter Kyle, the Secretary of State for Science, Innovation and Technology, has stated: ‘If the government is using algorithms on behalf of the public […] the public needs to feel that algorithms are there to serve them and not the other way around.’[3]

There are also more practical reasons to align with the public when it comes to decisions about data and AI.

Dissatisfaction with or concerns about how data may be used can lead to significant numbers of the public withdrawing consent, undermining the representativeness of datasets and the quality of AI tools that deploy those datasets. Notably, anxiety about the proposals to increase the sharing of health data under the General Practice Data for Planning and Research (GPDPR) led to three million people opting out of sharing their data, despite high baseline levels of trust in the NHS more generally. When the Department for Education agreed to share pupil data with the Home Office for immigration enforcement, a campaign to boycott the school census led to the school not obtaining nationality and country of birth data for almost a quarter of pupils.[4]

Public dissatisfaction has also led to specific tools being withdrawn. An instructive example is Ofqual’s A-level grading algorithm, which determined pupils’ grades when exams had to be cancelled due to COVID-19 in 2020. The perceived illegitimacy of the tool – particularly regarding differential effects – led to protests, the tool being withdrawn and a scramble to reallocate grades. This is a cautionary example for a number of reasons. The real-world harm was evident, as pupils initially missed out on university places due to the algorithmically-generated results which were then changed.[5] The effects were also felt beyond the rejection of the A-level tool: public dissatisfaction was so high that other AI projects around education were shelved, due to the loss of public trust.[6]

As well as these examples of direct public backlash, our research has identified instances where perceptions of potential illegitimacy have undermined the successful use of AI tools, even without explicit challenge.[7] In our research with social workers (Critical analytics?), interviewees expressed their discomfort about using a predictive tool for children’s social care.[8] Some social workers felt that residents might not see the tool as legitimate, despite receiving reassurance of its legality. As one interviewee put it: ‘I’m not sure, necessarily, that the man in the street would expect the data that’s held on them in a social care system to be held alongside other data as well for other uses.’[9]

There are even more profound risks to getting data collection wrong in the eyes of the public. If people have concerns about how information about them will be used, it could make them more reluctant to engage with services, leading to harm for the individual and a potential increase in costs or other significant knock-on effects across the public sector. In 2017, Public Health England raised concerns that the decision to share non-clinical health data with immigration enforcement could harm individuals, as well as threaten public health and increase healthcare costs due to delayed treatment and bed-blocking.[10]

In an era of growing mistrust in public institutions and traditional democratic processes, it is even more important for AI in the public sector to be seen as trustworthy.[11] People’s main interactions with the state occur through public services.[12] There have been high-profile examples of technologies that are perceived as unfair or illegitimate, such as the Post Office and Horizon scandal.[13] These cases have the potential to damage people’s trust and comfort in the use of technology in the public sector, and even to undermine the perceived legitimacy of services and of the behaviour of government itself.

Our research

Understanding public expectations and experiences of AI in the public sector will be crucial to identifying the conditions for its successful use, which is when it is trusted, effective and delivers positive outcomes for people and society.

As the UK government develops policy, strategy, guidance and regulation on using AI in the delivery of public services, it is imperative that policymakers have a robust understanding of public expectations to ensure that decisions about data, technology and services reflect the communities they seek to serve.

This briefing aims to support policymakers to build that understanding, through a synthesis of research by the Ada Lovelace Institute (Ada) on public attitudes and expectations around the use of AI in the public sector and the delivery of public services. We summarise evidence and findings from independent research undertaken between 2019 and 2025.

This research spans quantitative and qualitative research, engaging with almost 16,000 people through four nationwide attitudinal surveys and nearly 400 people in deeper qualitative studies. We collated research which engages with questions about the deployment of AI in the public sector or focuses on particular public services, including health technologies and systems, biometrics and policing, welfare, social care and transport. We also included research findings that focus on AI more broadly, for example around governance, where they are of relevance to the deployment of AI in public services.

A fuller discussion of the methodology, limitations, studies, samples, methods and topics can be found in the Appendix.

This empirical review has involved close reading and a collaborative analysis of evidence. It is informed by practice-based knowledge, as well as our current understanding of AI policy and practice in the UK.

The briefing is organised around six findings, which identify themes that have reoccurred across different use cases, populations and methodologies. While this is a limited review, intended to support a summarised account of our work rather than acting as a full literature review, we hope it will be of value for policymakers and practitioners involved in AI in the public sector.

Findings

1. There is no single view of AI: public perceptions are nuanced and context-dependent

‘Using it [biometric technology] for self-identification, for example to get your money out of the bank, is pretty uncontroversial. It’s when other people can use it to identify you in the street, for example the police using it for surveillance, that has another range of issues.’

– Juror, The Citizens’ Biometrics Council[14]

The public have nuanced views about AI applications rather than a single, overarching opinion on AI. People weigh the benefits, opportunities, risks and harms of specific applications within their particular contexts. Our research has shown how the public identify and understand both the benefits and risks of AI, including examples of support for AI tools where there is clear societal benefit.[15]

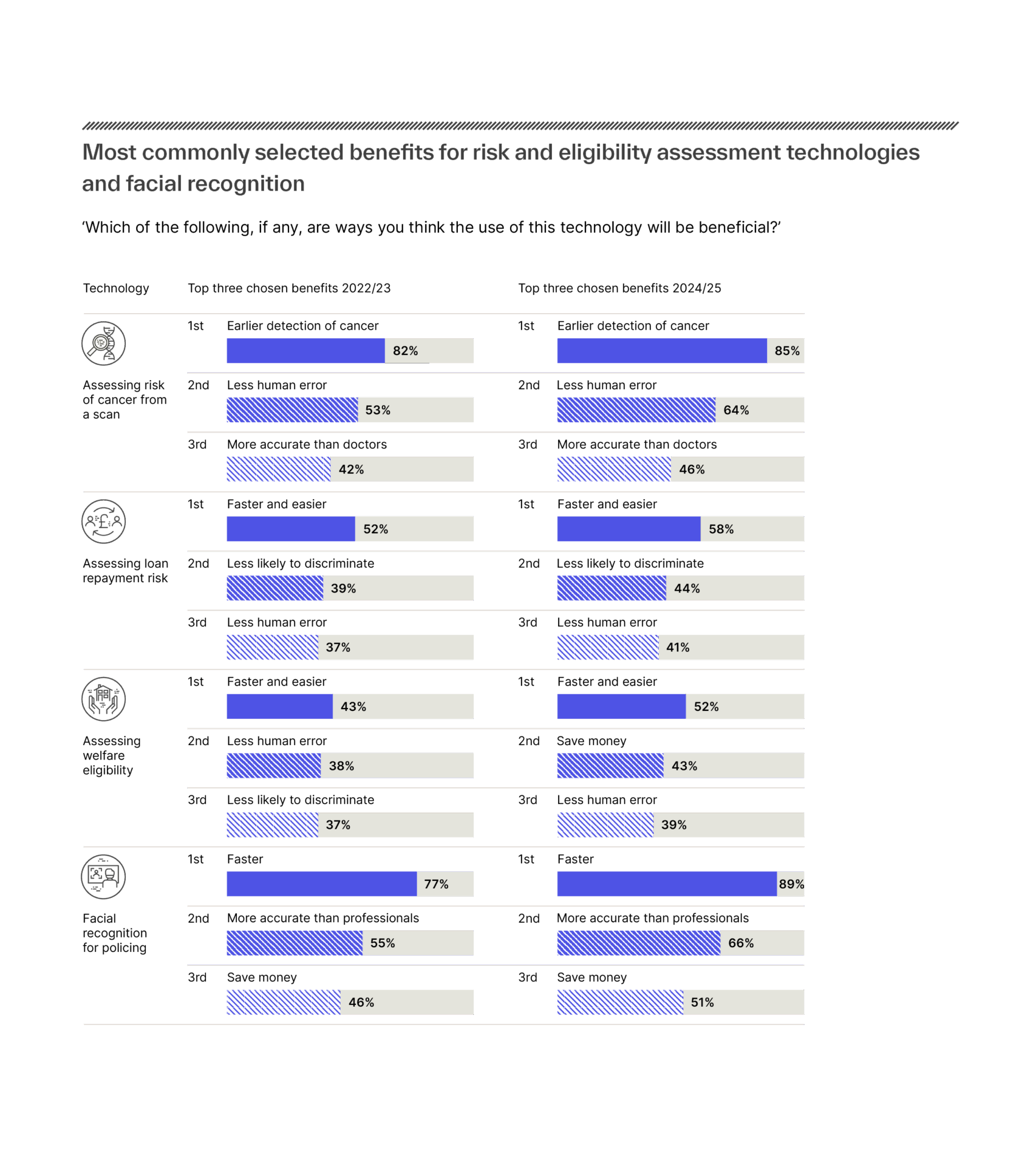

For example, in the nationally representative survey of public attitudes to AI by the Ada Lovelace Institute and the Alan Turing Institute in 2025, the respondents identified the following potential benefits of AI:

- Welfare eligibility assessments would be faster and easier, involve less human error and be likely to save money.[16]

- Cancer risk assessments would enable earlier detection of cancer, involve less human error and be more accurate than doctors.[17]

- Facial recognition for policing would be faster, more accurate and cheaper.[18]

Figure 1: The most commonly selected benefits for risk and eligibility assessment technologies and facial recognition

Potential benefits were also highlighted in our deliberative research in 2022, in which citizen jurors considered the good governance of data in pandemics (The rule of trust).[19] Some jurors thought that COVID-19 risk-scoring algorithms could be used in the long term to generate data that complemented community awareness and understanding. They thought the algorithms could be used to identify – and address – non-medical risks related to housing, economic hardship or food poverty.

Our public deliberation on AI and public good with communities in Belfast, Brixton and Southampton (Making good) identified that the public think AI could play a part in increasing the efficiency of public services, if it resulted in improvements in service provision in areas like transport, education and health services, as well as better quality of life.[20]

However, public views are nuanced and depend on context. Even in discussions on a specific technology, such as our in-depth public deliberation on biometric technologies in 2020 (The Citizens’ Biometrics Council), the public clarified that their comfort levels varied across different applications, depending on the nature and rationale of their deployment, and how they were governed and assessed for proportionality.[21]

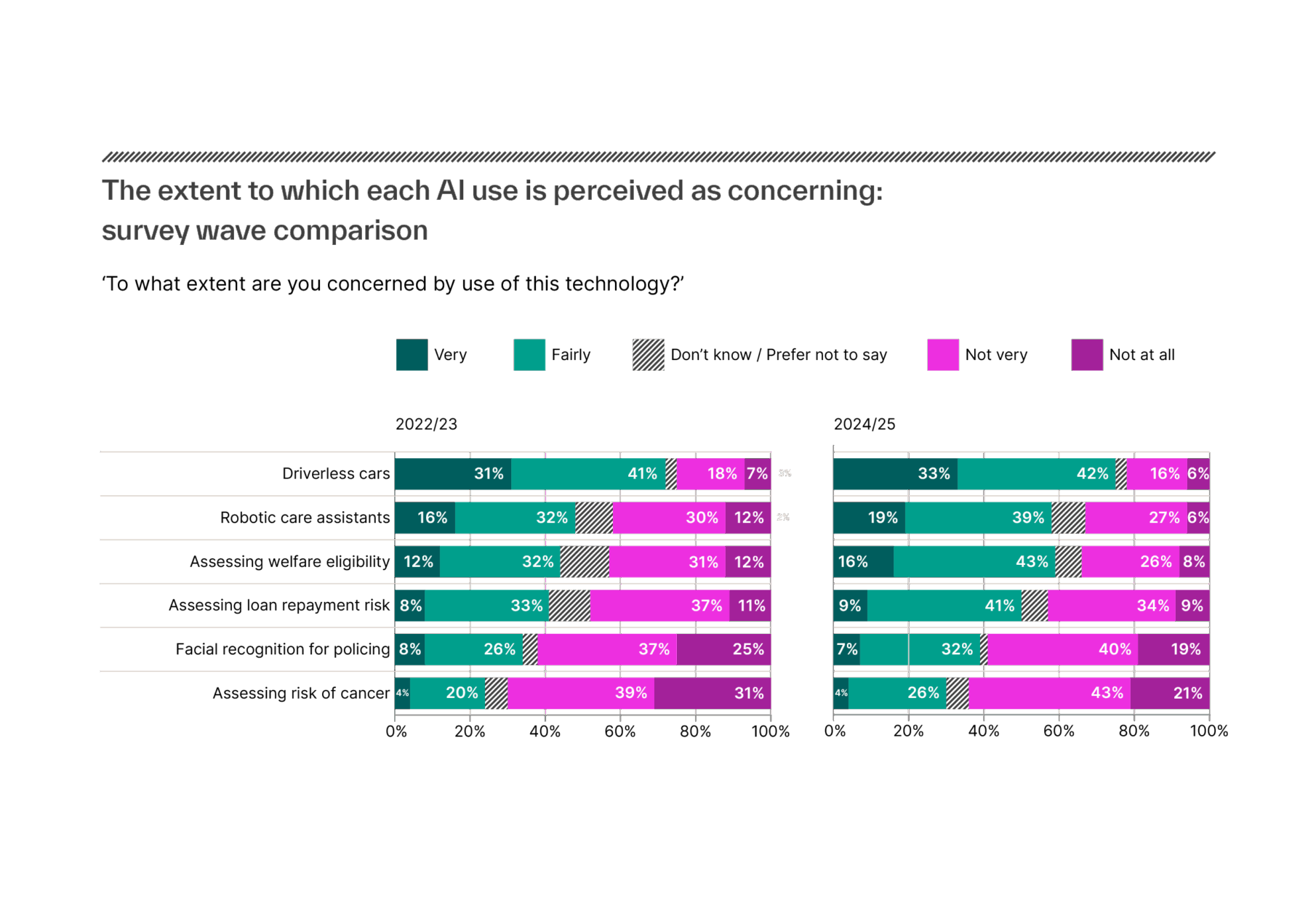

Even where AI is seen as broadly beneficial, the public still identify specific concerns regarding the potential consequences or effects of the same technologies.[22] In fact, these concerns have become more prominent in our data over time. Between the 2023 and 2025 waves of the Ada-Turing survey, the public’s perceptions of the benefits of AI remained stable. However, concern levels increased when we asked specifically about attitudes to specific public sector use cases. For facial recognition in policing, concerns increased from 34 per cent to 39 per cent; for cancer risk assessment from 24 per cent to 30 per cent; and for welfare eligibility assessment, from 44 per cent to 59 per cent.[23]

Figure 2: Levels of concern around specific uses of AI

Our research has also found that such concerns about AI do not necessarily reflect a lack of awareness or understanding, and increased awareness will not necessarily increase public trust in AI.[24]

2. Experiences and demographics shape people’s expectations

‘People with a history of being targeted might have that distrust that this info won’t be weaponised. It’s happened before.’

– Participant, Confidence in a crisis?[25]

‘And when it comes to the Home Office [using AI], that does indeed scare me. See, being an asylum seeker is already a whole turmoil of sadness in itself. We know AI lacks the emotion and critical thinking of a human.’

– Belfast participant, Making good[26]

Across different studies, we have found evidence that public views on AI are related to a person’s own experiences of technology and the context in which the technology is used. For example, attitudes to biometric technologies are influenced by previous negative interactions with ‘law enforcement, state, justice and other public and private institutions’.[27]

People who have experienced the introduction of poor-quality digital tools into public services have voiced concerns about the harmful knock-on effects of technology adoption. In our public deliberation on AI and public good (Making good), participants shared concerns about the adoption of AI. These concerns were shaped by their experiences of underfunded health systems and digital tools that had previously made services less accessible or useful. Their experiences of digital tools that had been brought in as ‘cost savers’ or ‘cut-throughs’ undermined expectations that AI would be applied appropriately or beneficially. Participants were concerned that the health system in particular would prioritise investment in AI over investment in medical staff who provide care. In Making good, we intentionally included people who are often excluded from research and decision-making, and the concern that AI might not meet their needs was particularly pronounced.[28]

This view was similarly held by participants in our deliberation on health data partnerships (Foundations of fairness).[29] Participants strongly believed that improving health outcomes should be the primary purpose of health data partnerships. However, based on their experiences with NHS services and new technology, they were sceptical that the promised benefits would be achieved.

Collecting survey data on public views on specific use cases has exposed some areas where AI use in the public sector is contentious or sensitive for specific groups. The 2025 Ada-Turing survey found that attitudes to AI varied with some demographic characteristics. People on lower incomes were more likely to be concerned about nearly all of the AI use cases in the survey.[30] We also noted demographic disparities when eliciting opinions on police surveillance, as well as governmental surveillance more generally. The analysis revealed that Black and Asian people were disproportionately likely to be concerned about facial recognition in policing.[31]

This reinforced qualitative findings from our public deliberation on biometric technologies (The Citizens’ Biometrics Council). We held community workshops with people from minority ethnic groups, members of the LGBTQI+ community and people with disabilities, who highlighted concerns regarding the use of technology which intersected with their lived experiences:[32]

‘I had to fight very hard to get my passport changed from male to female 30 years ago and I don’t want something on there to say this person was once a man, I just don’t want it. I want my recognition.’

– Citizen from the Brighton Community Voice workshop, Making visible the invisible[33]

‘Apps like Google Home and Siri don’t always work if you have a speech impairment, etc. This is another challenge – are we going to be maintaining appropriate and accessible services for people? Are there going to be people who cannot access all of these things?’

– Citizen from the Manchester Community Voice workshop, Making visible the invisible[34]

Our qualitative research has engaged with the public at a community level and sought to understand the experiences of people often excluded from power. This research demonstrates that people’s views around AI reflect their experiences of structural inequalities and distrust of power holders. This is an area that warrants further study.

3. Private profits, public doubts: there are concerns about the power and profits of technology companies in public services

‘Can AI fix any issue if profit is at the heart of it?’

– Belfast participant, Making good

Across our research, the public have raised concerns about the role, motivations and impacts of private companies developing and using AI in the public sector. This finding was echoed in an array of other studies we consulted in our broader evidence reviews.[35]

In our public deliberation on COVID-19 technologies (Confidence in a crisis?), participants expected transparency about the nature of arrangements between the public sector and private companies, especially large (and powerful) technology companies.[36] Our public deliberation on AI and public good (Making good) with communities in Belfast, Brixton and Southampton identified strong sentiments that AI should be used to further human and community needs, and should prioritise people over profit or ideology.[37] As one participant in Belfast stated: ‘Can AI fix any issue if profit is at the heart of it?’[38]

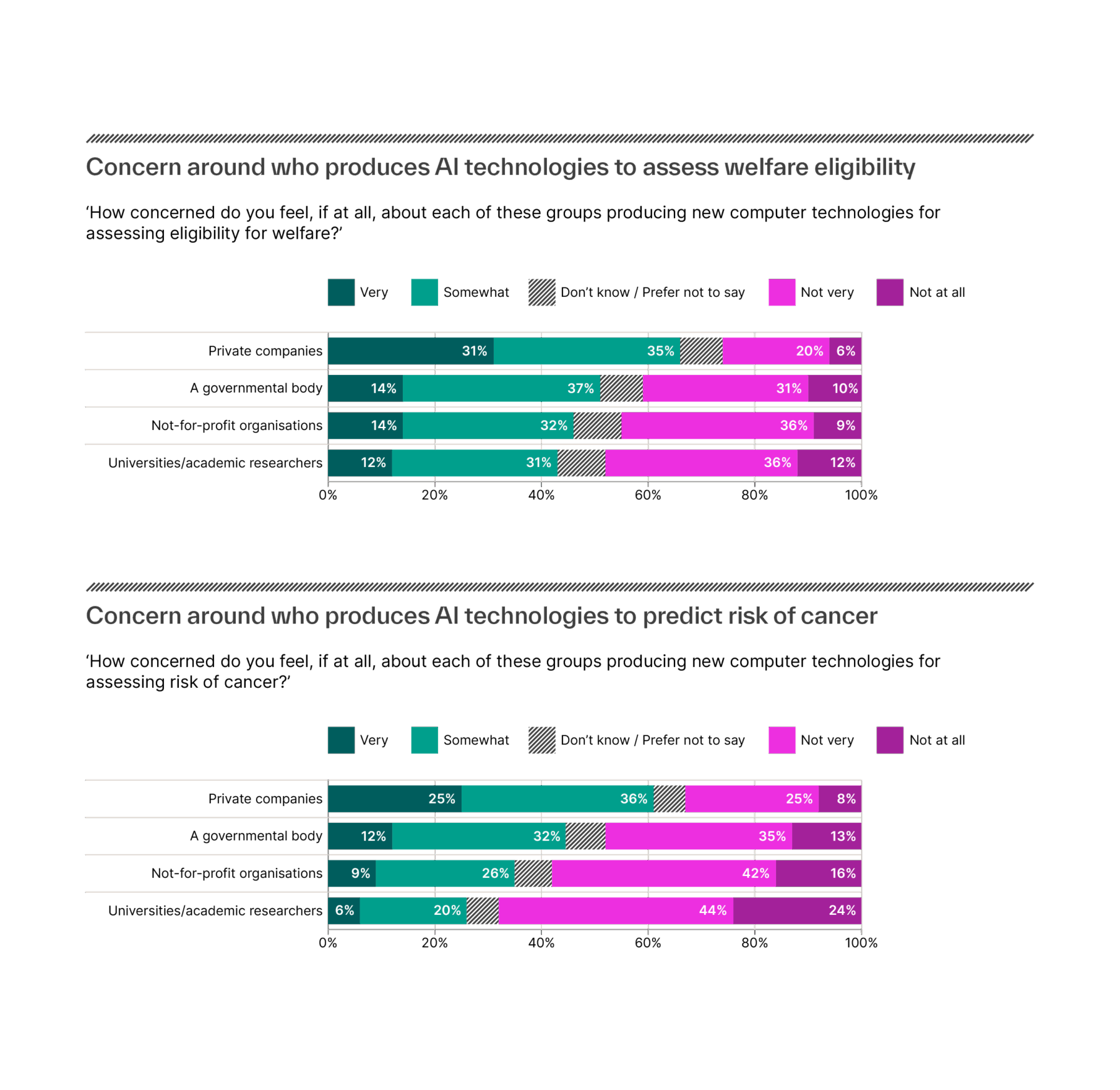

In the 2023 Ada-Turing survey, respondents were asked about their concerns (if any) with external actors producing AI technologies in two public sector use cases: AI technologies for predicting the risk of cancer, and for assessing eligibility for welfare benefits. In both examples, the majority of respondents were concerned about the involvement of private companies. These concerns were substantially higher than their concerns about third party involvement from other government bodies, not-for-profit organisations or academic researchers.[39]

Figure 3: Levels of concern around who produces AI technologies to assess welfare eligibility or predict the risk of cancer

Concerns about the role of private technology companies intersected with concerns about inadequate regulatory power. At the invitation of the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO), we reconvened the Citizens’ Biometrics Council in 2022 to review the ICO’s revised guidance on biometrics (Listening to the public).[40] In that discussion, respondents raised concerns about the ‘teeth’ of the regulator compared to the power of technology companies.[41] As one respondent put it: ‘But what are the penalties? […] If it’s a couple of million here or there, someone like Elon Musk can just take it out of the bankroll, and say, “Here you go, keep the change.”’[42]

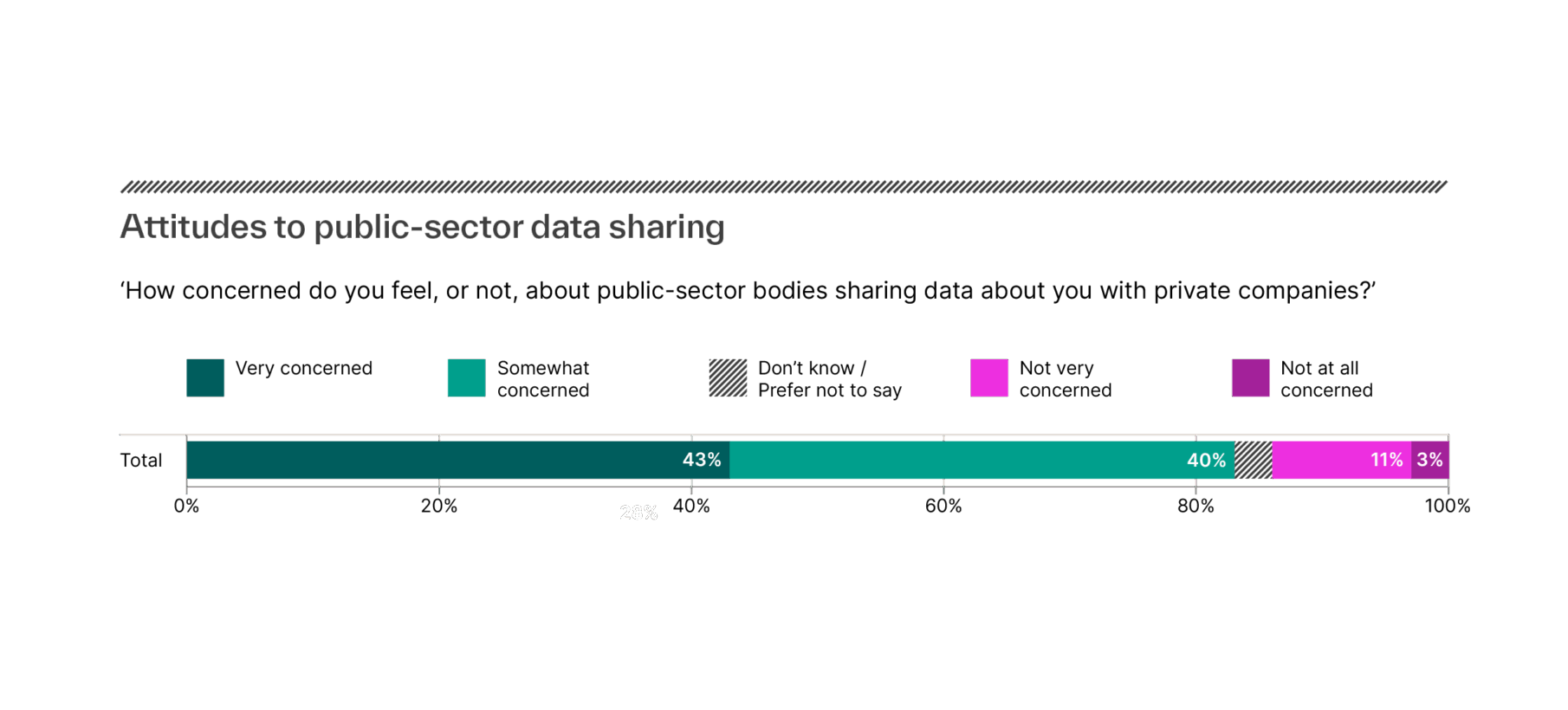

The public are particularly concerned about public sector bodies sharing information with private technology companies. Eighty-three per cent of respondents to the 2025 Ada-Turing survey were concerned about public sector bodies sharing personal information with private companies to train AI models.[43]

Figure 4: Attitudes to public-sector data sharing

In our quantitative and deliberative research on health data partnerships (Foundations of fairness), we found that the public expect the NHS to recognise the value – in more than monetary terms – of the data that it holds. They expect that adequate governance and expertise is in place to protect this data from exploitation by third parties.[44] This view was echoed by participants in our deliberative research on AI-powered genomic health prediction (Predicting: The future of health?).[45]

4. Support is conditional: the public want evidence, explainability and involvement

‘If we all know what’s going on, we can all be okay with it. If we don’t really know what’s going on, it just feels like Big Brother doesn’t it.’

– Participant, The Citizens’ Biometrics Council[46]

Our research has highlighted common themes about the conditions for public comfort with AI use in public services.

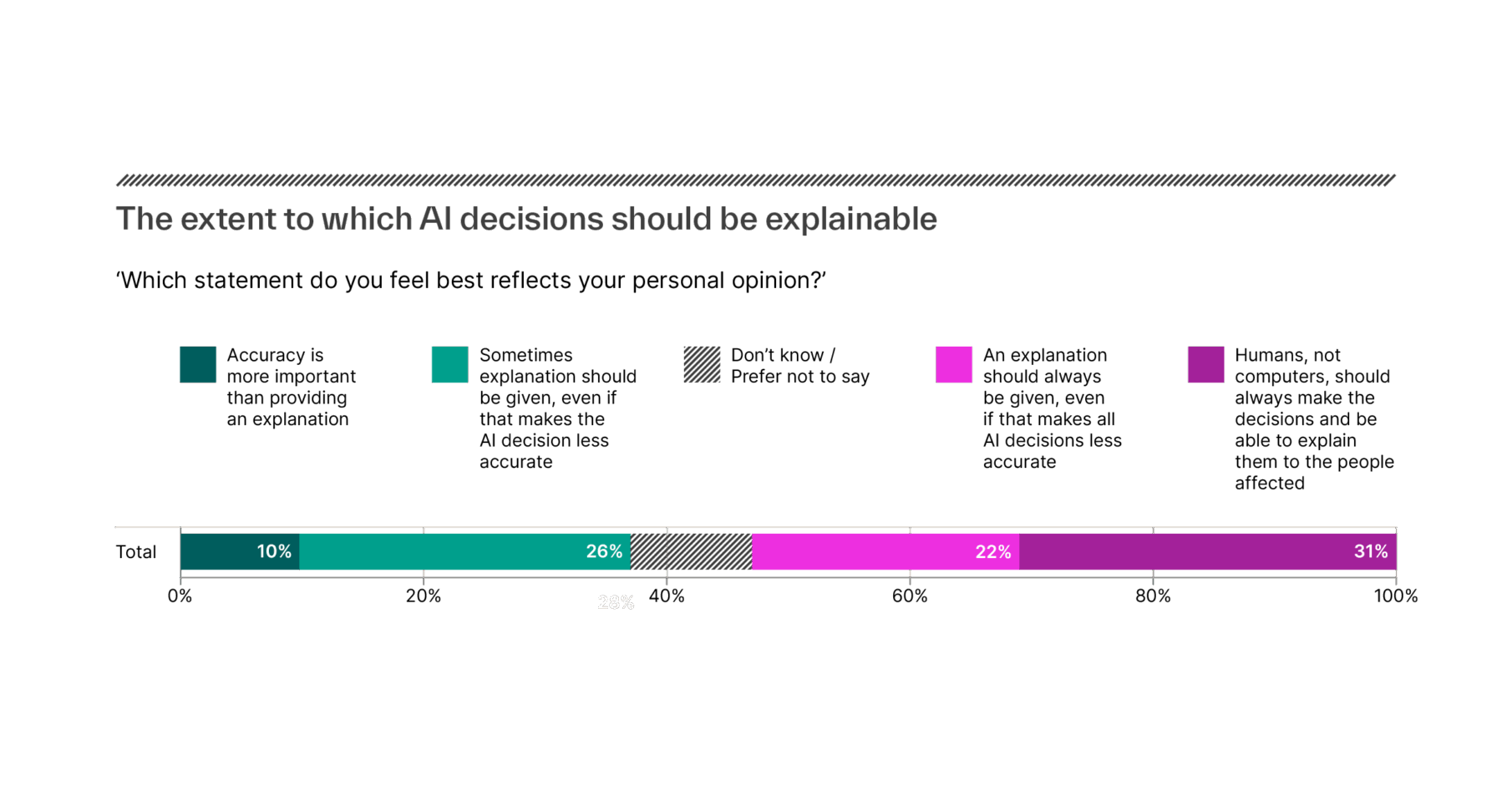

Our quantitative research shows that the public want to understand how decisions using AI are made. In the 2023 Ada-Turing survey, only 10 per cent of respondents felt that ‘accuracy is more important than providing an explanation’ when it comes to AI decision-making.[47]

Figure 5: The extent to which AI decisions should be explainable

As well as the importance given to the explainability of AI decision-making, the public have raised concerns about the basic levels of transparency around AI in public services. In our research on AI and public good (Making good), for example, participants reflected that AI is already used in many aspects of public services, but this is intentionally hidden from view. As one respondent put it: ‘I think in a lot of ways it is used in our lives already, but probably in a slightly underhand way that we don’t always know about.’[48] In the two waves of the Ada-Turing survey, the amount of people who expressed concerns about the transparency in decision-making when AI is used to assess cancer risk rose from 32 per cent in 2023 to 41 percent in 2025.

Much of the public participation research we have conducted over the past six years has underscored the importance of evidence about the impact and effectiveness of AI. One conclusion from the participants in Making good was that AI should be deployed only where necessary and effective. There was a desire that any decision about the design and delivery of AI should be grounded in robust information and research that publics could review.

In the context of a public health emergency, when the public may be asked to use and adapt to new technologies in a short space of time, the need for evidence is viewed as especially important. Our public deliberation on COVID-19 technologies (Confidence in a crisis?) found that the public would like to see clear, accessible evidence on which technologies are effective and under what conditions.[49] Our quantitative research examining social and health inequalities during the COVID-19 pandemic (The data divide) found that a significant proportion of people who chose not to use contact-tracing or symptom-tracking apps did not believe that the apps were accurate, or that they would improve their own health or the health of others.[50]

The public need more than evidence about effectiveness to be reassured that technologies in the public sector will work for them. Much of our qualitative work has revealed entrenched worries that potential overreliance on technology in important services will result in a loss of compassion and ‘the human touch’.[51] These worries can be especially acute in areas where they feel these qualities are most needed, such as for health and social care or immigration.[52] In Making good, participants pushed back against any AI deployment in healthcare that would substitute human care with automation and that risked a reduction in professional skills. They also shared concerns that AI might erode capacities for empathy.[53] Interview participants in Ada’s peer-led research study on socioeconomic inequalities in healthcare (Access denied?) expressed concerns that digital health services are making care less personal, less flexible and more fragmented. This was especially true for people with complex needs, higher health burdens or who are ‘digitally excluded’.[54]

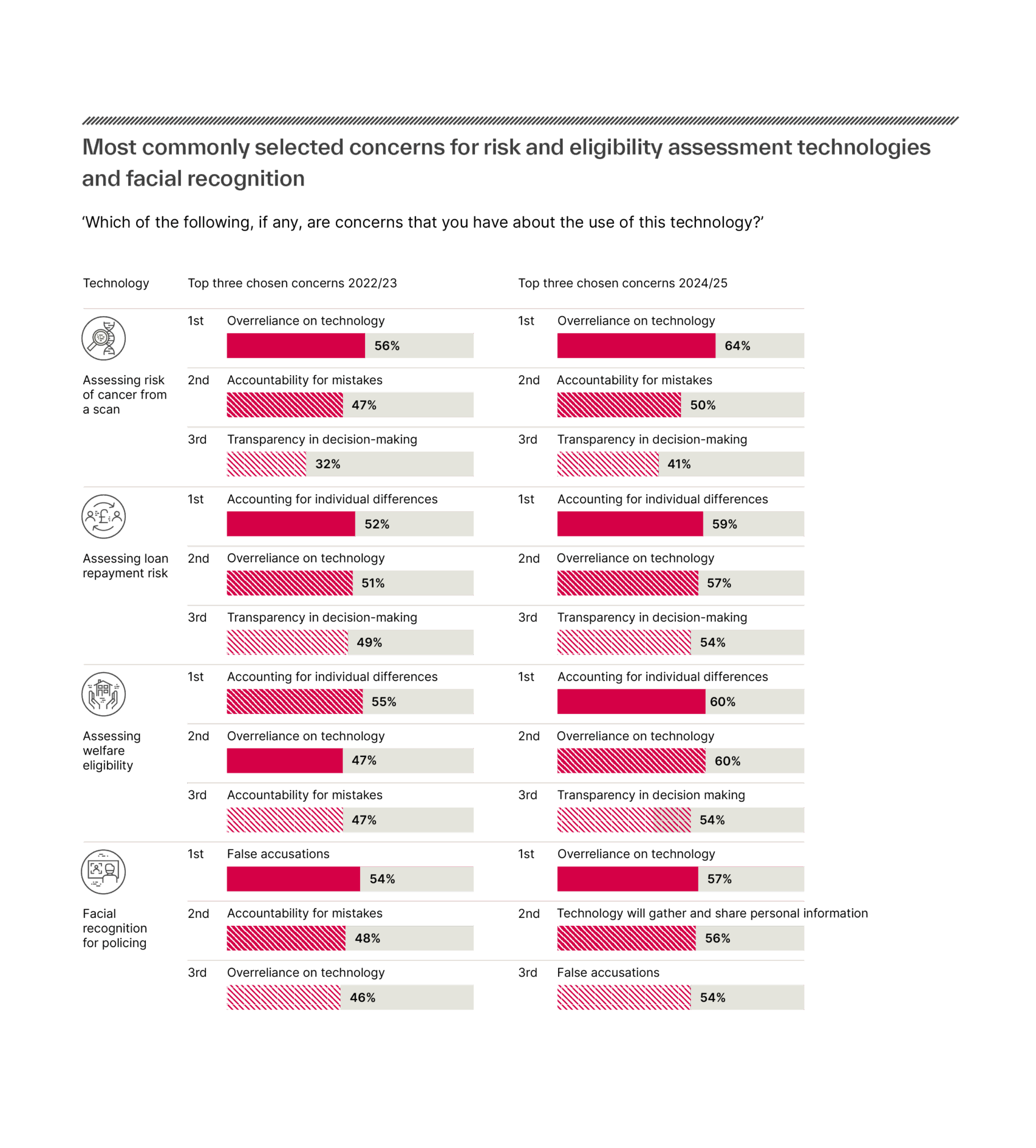

The public are also concerned that AI could reduce human involvement in high-stakes decisions that could affect lives.[55] In the 2025 Ada-Turing survey, ‘overreliance on technology’ was the most common concern cited by respondents about the use of AI in assessing cancer risk, assessing eligibility for welfare benefits, and facial recognition for policing, with a greater proportion of the public expressing concern since the 2023 survey.[56]

Figure 6: The most commonly selected risks for risk and eligibility assessment technologies, and facial recognition

Citizens’ juries on the governance of data in pandemics (The rule of trust) concluded that data-driven technologies ‘should not be used to surveil, influence, profile or predict the behaviour of individuals’.[57] The Citizens’ Biometrics Council in 2020 recommended that biometric technologies should not be rolled out on a large scale until legislation and an independent oversight body were in place, with assessments for both accuracy and proportionality.[58]

Participants in our quantitative and deliberative research on health data partnerships (Foundations of fairness) emphasised the importance of accountability and transparency for fair use of health data, including proactive communication, fulfilling reporting requirements and placing information on websites.[59] Eighty-two per cent of respondents to the survey component of the research expected the NHS to publish information about data partnerships with third parties.[60]

5. Strong governance is a prerequisite for trust

‘The most important thing is to be able to query it, challenge it. Because I don’t want to be misidentified…’[61]

– Juror, The Citizens’ Biometrics Council

‘We want somebody to make sure that all this biometric data … which is a great, powerful tool … is well maintained and regulated, and used responsibly.’

– Juror, The Citizens’ Biometrics Council

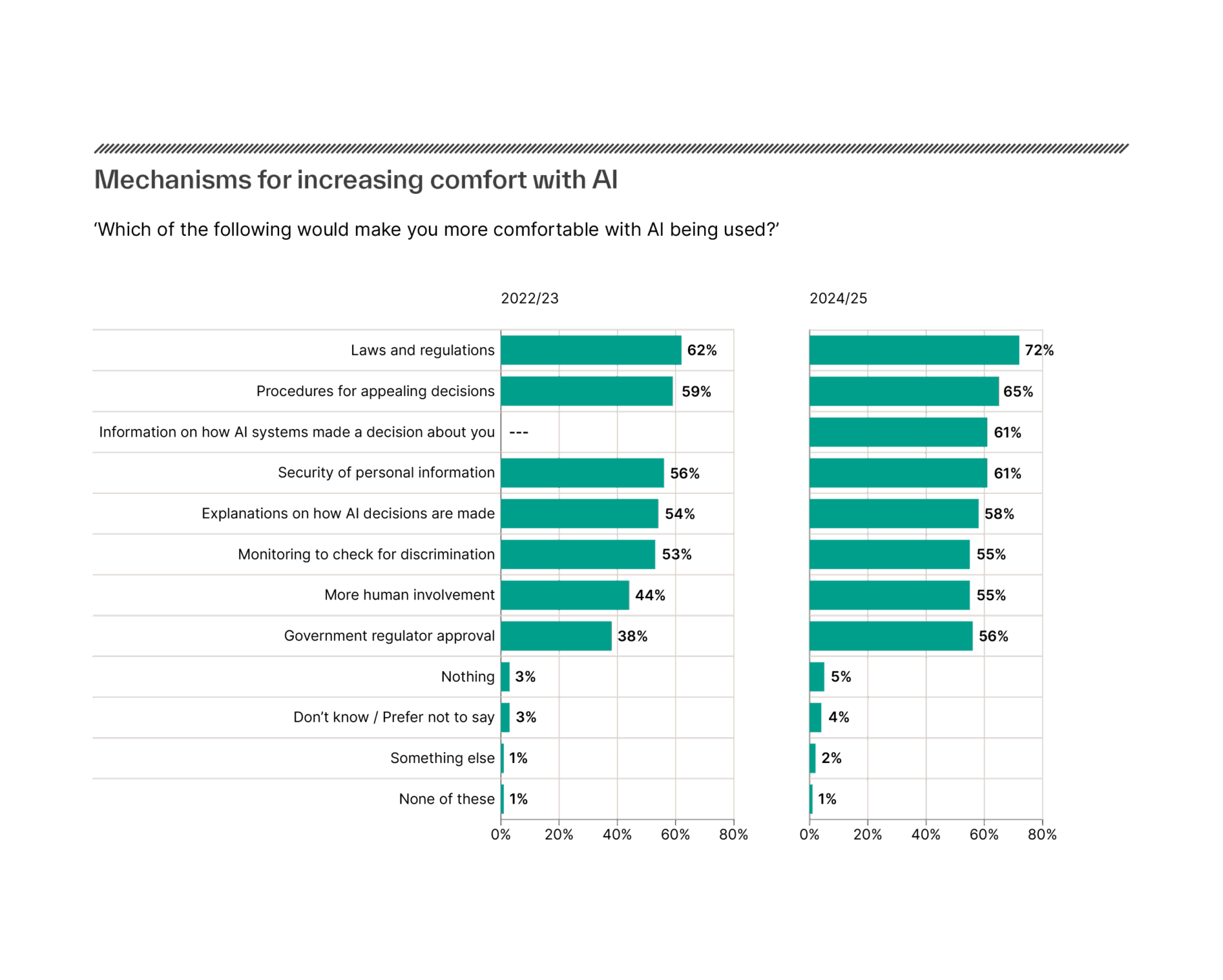

The public would like to see regulation on the use of data and AI and expect governance structures to be trustworthy.[62] [63] Sixty-two per cent of respondents to the 2023 Ada-Turing survey were in favour of ‘laws and regulations that prohibit certain uses of technologies and guide the use of all AI technologies’.[64] By 2025, this had increased: 72 per cent of respondents reported that laws and regulation would make them more comfortable with AI.[65]

Figure 7: Mechanisms for increasing comfort with AI [66]

The public expect government and/or regulators to have a suite of powers related to the governance of AI. For example, to stop the use of a product if it poses harm, to monitor risks posed by AI systems and to develop safety standards.[67] The public consistently identify the need for a multifaceted governance system.

The public would also like to see measures to ensure that AI systems are not the sole basis for decision-making. It is important to the public that if an AI technology makes a mistake, then there are options for redress.[68] In 2025, 65 per cent of respondents reported that appeals procedures would make them more comfortable with AI use (up from 59 per cent in 2023).[69]

The desire for strong governance was reinforced in several of Ada’s in-depth deliberative research projects about specific use cases in the public sector. Participants in our deliberation on health data partnerships (Foundations of fairness) did not think a set of guiding principles for NHS bodies was sufficient. Instead they argued for a governing body and for proactive, monitoring and reactive areas of governance.[70] Participants in the Citizens’ Biometrics Council expressed a clear recommendation for legislation, regulation and an independent oversight body for the use of biometrics. They recommended that the technologies should not be widely deployed until these are in place.[71] When we reconvened the Citizens’ Biometrics Council to review the ICO’s proposed guidance (Listening to the public), the members felt the guidance needed strengthening: ‘It’s great having all these guidelines and stuff, but in terms of power, the legislation and the laws aren’t really effective I don’t think.’[72]

Our insights on AI and public good from communities in Belfast, Brixton and Southampton (Making good) identified that the public do not see public benefit as automatically following from progress and innovation. Consequently they expect action and values-based governance for AI to work in the public interest.[73]

Our research has consistently found that the public would like more meaningful involvement in the development and implementation of AI, as well as policy decision-making, and to engage with and shape decisions about technologies that have social impact.[74] [75] Citizen jurors on the good governance of data in pandemics (The rule of trust) emphasised the importance of acknowledging people’s lived experiences of technology design and use, and of taking a ‘bottom-up’ approach that starts from people’s experiences.[76] Seventy-four per cent of participants in the Foundations of fairness survey on health data partnerships believed that the public should be involved in decisions about how NHS data is used.[77]

The public want their opinions to be valued, not just heard.[78]

6. Social impact matters: the public oppose uses of AI that could create a ‘two-tier society’

‘I am worried about the way biometrics are going. […] What is it doing for disabled people? We’ve just seen videos of using hands and I’ve got no chance because my fingers aren’t straight. So what’s going to happen with people like us, are we going to be left behind?’

– Juror, The Citizens’ Biometrics Council[79]

A recurring theme in public attitudes towards the use of AI in the public sector is the exacerbation of inequalities. This is often expressed through fears that the use of AI in the public sector could create a ‘two-tier society’.[80] Across different contexts, the public are deeply concerned about the adoption or normalisation of technologies that could exacerbate inequalities or disadvantage certain groups when it comes to public sector access, use and experiences.[81]

For example, when considering COVID-19 risk-scoring algorithms, citizen jurors emphasised the importance of using them in non-stigmatising ways (The rule of trust).[82] They expressed a clear red line: ‘Technologies should not create a two-tiered society that disproportionately discriminates against or disadvantages certain groups.’[83] In the 2022 Citizens’ Biometrics Council (Listening to the public), respondents raised concerns about the normalisation of technology disadvantaging those with disabilities or bodies that are deemed not to fit the norm.[84]

In our research on AI-powered genomic health prediction (the application of AI-powered analysis to a person’s genomic data to make predictions about their health, their risk of developing non-transmissible diseases, and their response to drugs and medication), participants expressed concerns about disease risk-scoring being used to compound inequalities and as a basis for unfair discrimination (Predicting: The future of health?).[85]

Participants voiced their worries about the potential use of disease risk-scoring that might excessively shift responsibility from the state and the NHS onto individuals, and how this could create unfair and unrealistic expectations for people to action their disease risk-scores and keep themselves healthy. It was noted that this pressure would be felt very differently by different groups of people. While those on high incomes might find these risk-scores to be useful and actionable, people on low incomes (and especially those at higher risk of disease) may lack the time and resources to make use of this information. They may experience them as a source of worry, especially if risk-scoring is used by medical professionals to make decisions about healthcare provisions.

Participants also worried about potential scenarios in the future where disease risk-scoring tools might be used to inform insurance premiums. Participants were notably concerned by the idea that those deemed more likely to fall ill as a result of their DNA – and therefore most in need of the protection provided by insurance – would be likely to face higher costs.

Our research has consistently found that non-discrimination, fairness and equity are key values for the public.[86] These underpinned conversations on various policy areas in our public deliberation on AI and public good (Making good), such as transport and education.[87]

Participants in our research on the use of health data (Foundations of fairness) emphasised that fairness should include distributing benefits across the entire health system, to ensure that existing regional healthcare inequalities are not exacerbated. Eighty-one per cent of participants believed that benefits from data partnerships should be distributed across different areas of the country, and not be limited to the region where the partnership is located.[88]

The public expect AI design, deployment and policy to accommodate pluralism and diversity, so that these technologies deliver public benefit that is widely felt.

People want AI to work for those with different needs and vulnerabilities.[89]

Recommendations

This review of our research on public attitudes emphasises the need to strengthen transparency and evidence around the use of AI, as well as the need for further research on public acceptability and conditions. It highlights the need for greater examination of the relationship between private technology companies and public sector entities.

In our publication Building blocks, we proposed four targeted recommendations to strengthen the foundations for AI in the public sector.[90] In light of this review, we believe these recommendations are of renewed importance for those working on the delivery of AI in the public sector, particularly for the UK’s digital centre of government.

1. Strengthen the Algorithmic Transparency Reporting Standard to deliver on public expectations for transparency. Government should consider public expectations for transparency and assess whether the Algorithmic Transparency Reporting Standard (ATRS) is meeting those expectations. Government could also examine whether and how to reflect the uses of novel AI technologies in the register (including general-purpose tools and ‘slipstream’ AI tools that are automatically integrated into existing software, like Microsoft Copilot).

It should also investigate how the ATRS could contribute to the existing taxonomical classification of AI products produced by the UK’s Incubator for Artificial Intelligence (i.AI), by identifying and grouping clusters of algorithms with similar technical features, purposes and contexts of use.

2. Set up a What Works Centre for AI in public services to bring together and disseminate learnings from pilots and evaluations. This could complement the Evaluation Task Force’s new annex to the Magenta Book and contribute to the ‘learn’ aspects of the government’s ‘test and learn’ approach to improving public services, by complementing a strengthened ATRS and other repositories such as i.AI’s ‘Use Case Library’ and the Local Government Association’s ‘Use Case Bank’ with rigorous evaluative evidence.

A What Works Centre could interface with the independent Responsible AI Advisory Panel and bolster the work of the digital centre of government, supporting practitioners with access to best practice expertise to shape standards. It could alleviate public anxiety about undue private sector influence, by providing an independent source of rigorous evidence and guidance about the adoption of AI.

3. Create a taskforce for AI procurement, starting with a local government focus. Public sector procurement of AI must ensure that the systems proposed for use in government and public services are effective – addressing the needs of people and communities – as well as safe, fair, transparent, trustworthy and publicly legitimate. At present, local government procurers face challenges such as confusing guidance and legislation, uncertainty about how AI works and how it can be used, and data gaps. Procurers also face an imbalance between the capacity and expertise of local government and a private sector often dominated by monopolies.

To ensure holistic, joined-up reforms – rather than siloed or piecemeal changes – the government would be wise to create a National Taskforce for Procurement of AI in Local Government. This fixed-term body would bring together experts to create robust governance structures, templates for contracts, assessment frameworks and clear guidance. It would also gather evidence on best practices and design training for procurers, enabling them to critically engage with AI technologies and reduce their dependence on private sector suppliers.

4. Prioritise and fund participatory and public attitudes research on data and AI. This work should include future waves of public attitudes research which could help to identify key use cases that warrant more extensive public deliberation and where there might be opportunities to empower the public more directly to shape decisions about AI. This might include deliberations with frontline workers, services users and communities who might have particular needs, experiences or concerns regarding the use of data and AI in the public sector.

Ada’s research on biometric data provides a potential model for this. The Citizens’ Biometrics Council took evidence from experts with different perspectives on biometrics and used that evidence as the basis for deliberation by members of the public. This council developed recommendations which reflected their tolerance and red lines. Members of the council have since been reconvened to support the ICO with its guidance.

In light of public concerns about the role of private technology companies in the rapid integration of AI across key government functions and infrastructure, we make a further recommendation that the Science, Innovation and Technology Committee:

5. Initiate an inquiry into the private sector’s involvement in shaping government policy and procurement decisions related to public sector AI. This review should encompass the role of the private sector in providing (formal and informal) advice to government on the public sector’s use of AI; the role of technology companies and the bodies funded by them in shaping the policy and media narrative on the benefits of public sector AI; and the effectiveness of existing measures that aim to tackle conflicts of interest and ‘revolving door’ dynamics between government and the technology sector.

Conclusion

Research by the Ada Lovelace Institute (Ada) has consistently found that public perceptions of the benefits and risks of public sector AI are nuanced and context-dependent. The public are clear that there is not a single ‘public sector AI’ technology or use case, and they can identify both the benefits and risks of different AI uses, as well as identify different contexts and the differential experiences of people who are already marginalised.

At a time when AI is being offered as a solution to a wide range of public sector problems, the public are concerned about the motivations of private sector involvement. The public expect transparency and that public sector AI prioritises people over profit. This is especially important given that public awareness of AI in the public sector is low.

Public sector AI needs to be evidence-based, explainable and involve people in decision-making to ensure public acceptability. The public expect laws and regulations, as well as clear appeals and redress procedures if something goes wrong. Meaningful public involvement is also crucial for the development and implementation of public sector AI. While there is support for AI use where there is a clear public benefit, people expect to be meaningfully considered in determining if and how this is the case across the wide range of possible technologies and public sector use cases.

Over the last six years, Ada has been a significant contributor to societal knowledge about the deployment of public sector AI and what the public might think about it. We will continue to undertake research to explore different use cases across the public sector and we have made further research a central recommendation.

The rapid and often invisible adoption of AI in the public sector means there is a risk that AI use could outpace clarity about public acceptability. Data gaps, as suggested in our research, can reflect and illuminate the inequalities that people experience when engaging with services. More research and input are needed, particularly from those who experience structural inequalities.

Heavy public service users – including many people who are vulnerable – may be excluded from research processes and less visible to researchers. The domains or public services that they rely on are also less likely to generate significant societal or media attention, as they are people who are typically excluded from mainstream discourse. Combined with low levels of transparency in the public sector about what functions are being devolved to AI and their impacts, these experiences can be hidden from view. The opacity and complexity around AI may raise barriers to an informed public debate.

Moving in step with public legitimacy is crucial to support those engaging with public services and to support wider democratic processes, civic engagement and people’s faith in the public sector and government institutions.

Methodology

This briefing draws on quantitative and qualitative research across 14 research reports (listed in the table below), including research engaging with almost 16,000 people through four nationwide attitudinal surveys, and nearly 400 people in deeper qualitative studies. Research was incorporated where it explored people’s attitudes, expectations and deliberations about the use of data-driven technologies and AI in the public sector or by public services.

Particular areas of focus include health technologies, COVID-19 technologies, genomics, biometrics, welfare, care and transport. We also included research findings that were focused on AI more broadly, for example around governance, where they are of relevance to the deployment of AI in public services.

For transparency and a clear overview, we have set out the studies, samples, methods and topics in the Appendix below.

This research has used different methods, focused on different technologies and use cases, and engaged different populations across the UK. It has revealed consistencies in public views across these contexts, which have informed our insights according to where they may be useful or applicable to the public sector. We also point to areas where lack of consistency may indicate that further work should be done, or where public sector professionals should be cautious when interpreting the evidence on public views in particular areas of AI use.

Our research demonstrates the necessity of combining different methods (and different evidence) to develop a rich understanding of public views. This is not a toolkit of such methods, but we showcase the ways in which a variety – or combination – of methods has helped us to generate more informative evidence and a more nuanced understanding of public views about AI in the public sector.

Limitations

This briefing is based on research that Ada has produced over the past six years. Therefore it is a limited review, intended to support a summarised account of our work rather than acting as a full literature review on public attitudes towards AI in the public sector.

Some of the research was explicitly focused on public sector deployment of AI, while other projects included broader research aims. This briefing does not claim to comprehensively examine public views towards all potential uses or availabilities of technology that could be used in the public sector. Broader research is needed and we encourage public sector professionals to consider the relevance across our body of work, which is presented in the Appendix.

In this review, we discuss the evidence we have of where people from particular minoritised groups express views about some technological applications differently from other demographic groups. However we highlight the need for further research to enable us to understand views across different minoritised groups.

While our research highlights particular areas of difference, we do not claim that people’s views are differentiated solely by demographic markers, because people’s views are also shaped by direct and indirect experiences, and we argue that our findings are an indication that additional intersectional research is needed.

Terminology

In this report, we refer to ‘the public’ to distinguish citizens and residents from other stakeholders in our research, including the private sector, policy professionals and civil society organisations. We intentionally use the singular form of ‘public’ as a plural (‘the public think’) to reinforce the implicit acknowledgement that society includes many publics with different levels of power and lived experiences, and different levels of exposure to the opportunities, benefits, risks or harms of different AI uses.

Acknowledgements

This report was co-authored by Imogen Parker and Laura Carter, with substantial contributions from Eleanor O’Keeffe.

We are grateful for comments, contributions and support from Elliot Jones, Harry Farmer, Octavia Field Reid, Roshni Modhvadia and Matt Davies.

Appendix: Evidence from the Ada Lovelace Institute

| Title | Research method | Sample size | Public sector areas | Date |

| ‘Beyond Face Value: Public Attitudes to Facial Recognition Technology’ (2019) | Attitudinal survey | 4109 |

|

Sep-19 |

| ‘Foundations of Fairness: Where next for NHS Health Data Partnerships?’ (Ada Lovelace Institute and Understanding Patient Data, 2020) | Mixed methods: attitudinal survey, deliberative research |

2095 60 |

|

Mar-20 |

| ‘Confidence in a Crisis? Building Public Trust in a Contact Tracing App’ (Ada Lovelace Institute and Traverse, 2020) | Deliberative methods | 28 |

|

Aug-20 |

| ‘The Citizens’ Biometrics Council: Recommendations and Findings of a Public Deliberation on Biometrics Technology, Policy and Governance’ (2021) | Deliberative methods | 50 |

|

Mar-21 |

| ‘The Data Divide: Public Attitudes to Tackling Social and Health Inequalities in the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond’ (2021) | Attitudinal survey | 2023 |

|

Mar-21 |

| ‘The Rule of Trust: Findings from Citizens’ Juries on the Good Governance of Data in Pandemics’ (2022) | Deliberative methods | 50 |

|

Jul-22 |

| ‘Who Cares What the Public Think?’ (2022) | Rapid evidence review | 40 studies | Aug-22 | |

| ‘How Do People Feel about AI?’ (Ada Lovelace Institute and the Alan Turing Institute, 2023) | Attitudinal survey | 4010 |

|

Nov-22 |

| ‘Listening to the Public: Views from the Citizens’ Biometrics Council’ (2023) | Deliberative methods | 30 |

|

Aug-23 |

| ‘Access Denied? Socioeconomic Inequalities in Digital Health Services’ (2023) | Codesign research (peer research) | 31 |

|

Sep-23 |

| ‘What Do the Public Think about AI?’ (2023) | Rapid evidence review | 57 studies |

|

Oct-23 |

| ‘Predicting: The Future of Health?’ (2024) | Mixed methods, deliberative research | 24 |

|

Sep-24 |

| ‘How Do People Feel about AI?’ (Ada Lovelace Institute and the Alan Turing Institute, 2025) | Attitudinal survey | 3513 |

|

Mar-25 |

| ‘Making Good’ (2025) | Mixed methods: deliberative and codesign research (community research) | 47 |

|

Mar-25 |

Footnotes

[1] Imogen Parker, Anna Studman and Elliot Jones, ‘Learn Fast and Build Things’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2025) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/policy-briefing/public-sector-ai/> accessed 18 April 2025.

[2] ‘The Seven Principles of Public Life’ (GOV.UK, 31 May 1995) <https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-7-principles-of-public-life/the-7-principles-of-public-life–2> accessed 15 June 2025.

[3] Robert Booth, ‘UK Government Failing to List Use of AI on Mandatory Register’ The Guardian (28 November 2024) <https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2024/nov/28/uk-government-failing-to-list-use-of-ai-on-mandatory-register> accessed 26 May 2025.

[4] Freddie Whittaker, ‘Pupil nationality data: Controversial collection misses data for more than million pupils’ (Schools Week, 13 December 2018) <https://schoolsweek.co.uk/pupil-nationality-data-controversial-collection-misses-data-for-more-than-million-pupils/> accessed 1 May 2025.

[5] Elliot Jones and Cansu Safak, ‘Can Algorithms Ever Make the Grade?’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 18 August 2020) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/blog/can-algorithms-ever-make-the-grade/> accessed 26 May 2025.

[6] Imogen Parker, Anna Studman and Elliot Jones, ‘Learn Fast and Build Things’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2025) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/policy-briefing/public-sector-ai/> accessed 18 April 2025.

[7] Laura Carter, ‘Critical Analytics? Learning from the Early Adoption of Data Analytics for Local Authority Service Delivery’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2024) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/local-authority-data-analytics/> accessed 21 June 2024.

[8] ibid.

[9] ibid.

[10] Noel Gordon, ‘Correspondence Regarding Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between NHS Digital, the Home Office and the Department of Health on Data Sharing’ (6 March 2017) <https://www.parliament.uk/globalassets/documents/commons-committees/Health/Correspondence/2016-17/Correspondence-Memorandum-Understanding-NHS-Digital-Home-Office-Department-Health-data-sharing.pdf> accessed 15 June 2025.

[11] ‘Trust and Confidence in Britain’s System of Government at Record Low’ (National Centre for Social Research, 26 March 2025) <https://natcen.ac.uk/news/trust-and-confidence-britains-system-government-record-low> accessed 26 May 2025.

[12] Imogen Parker, ‘Why Public Legitimacy for AI in the Public Sector Isn’t Just a “Nice to Have”’ (Global Government Forum, 29 April 2025) <https://www.globalgovernmentforum.com/why-public-legitimacy-for-ai-in-the-public-sector-isnt-just-a-nice-to-have/> accessed 15 June 2025.

[13] Between 1999 and 2015, more than 900 Post Office employees were wrongly prosecuted for theft or fraud, after Fujitsu’s Horizon software incorrectly reported shortfall. See ‘Post Office Horizon Scandal: Why Hundreds Were Wrongly Prosecuted’ (BBC, 21 April 2021) <https://www.bbc.com/news/business-56718036> accessed 26 May 2025.

[14] Aidan Peppin, ‘The Citizens’ Biometrics Council: Recommendations and Findings of a Public Deliberation on Biometrics Technology, Policy and Governance’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2021) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/citizens-biometrics-council/> accessed 10 March 2025.

[15] Aidan Peppin, ‘Who Cares What the Public Think?’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2022) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/evidence-review/public-attitudes-data-regulation/> accessed 12 December 2024.

[16] Roshni Modhvadia, Tvesha Sippy, Octavia Field Reid and Helen

Margetts, ‘How Do People Feel about AI?’ (Ada Lovelace Institute and the Alan Turing Institute, 2025) < https://attitudestoai.uk/findings-2025/attitudes-towards-technologies/risk-and-eligibility-assessments-and-facial-recognition#64109/> accessed 18 April 2025.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Roshni Modhvadia, Tvesha Sippy, Octavia Field Reid and Helen

Margetts, ‘How Do People Feel about AI?’ (Ada Lovelace Institute and the Alan Turing Institute, 2025) <https://attitudestoai.uk/findings-2025/attitudes-towards-technologies/risk-and-eligibility-assessments-and-facial-recognition#64109

[19] Aidan Peppin, ‘The Rule of Trust: Findings from Citizens’ Juries on the Good Governance of Data in Pandemics’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2022) 41 < https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/trust-data-governance-pandemics/>

[20] Eleanor O’Keefe, ‘Making Good’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2025) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/ai-public-good/> accessed 23 April 2025.

[21] Aidan Peppin, ‘The Citizens’ Biometrics Council: Recommendations and Findings of a Public Deliberation on Biometrics Technology, Policy and Governance’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2021) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/citizens-biometrics-council/> accessed 10 March 2025.

[22] Octavia Field Reid, Anna Colom and Roshni Modhvadia, ‘What Do the Public Think about AI?’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2023) 11 <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/evidence-review/what-do-the-public-think-about-ai/> accessed 4 January 2025.

[23] Roshni Modhvadia, Tvesha Sippy, Octavia Field Reid and Helen

Margetts, ‘How Do People Feel about AI?’ (Ada Lovelace Institute and the Alan Turing Institute, 2025) < https://attitudestoai.uk/findings-2025/benefits-and-concerns#72304> accessed 18 April 2025.

[24] Roshni Modhvadia, ‘How Do People Feel about AI?’ (Ada Lovelace Institute and the Alan Turing Institute, 2023) 25 <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/public-attitudes-ai/> accessed 20 April 2025.

[25] Ada Lovelace Institute and Traverse, ‘Confidence in a Crisis? Building Public Trust in a Contact Tracing App’ (2020) 20 <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/confidence-in-crisis-building-public-trust-contact-tracing-app/> accessed 10 March 2025.

[26] Eleanor O’Keefe, ‘Making Good’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2025) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/ai-public-good/> accessed 23 April 2025.

[27] Reema Patel and Aidan Peppin, ‘Making Visible the Invisible: What Public Engagement Uncovers about Privilege and Power in Data Systems’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 5 June 2020) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/blog/public-engagement-uncovers-privilege-and-power-in-data-systems/> accessed 23 April 2024.

[28] Eleanor O’Keefe, ‘Making Good’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2025) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/ai-public-good/> accessed 23 April 2025.

[29] Understanding Patient Data and Ada Lovelace Institute, ‘Foundations of Fairness: Where next for NHS Health Data Partnerships?’ (Understanding Patient Data, March 2020) <https://understandingpatientdata.org.uk/sites/default/files/2020-03/Foundations%20of%20Fairness%20-%20Summary%20and%20Analysis.pdf> accessed 10 March 2025.

[30] Roshni Modhvadia, Tvesha Sippy, Octavia Field Reid and Helen

Margetts, ‘How Do People Feel about AI?’ (Ada Lovelace Institute and Alan Turing Institute, 2025) <https://attitudestoai.uk/findings-2025/benefits-and-concerns#72246> accessed 18 April 2025.

[31] Roshni Modhvadia, Tvesha Sippy, Octavia Field Reid and Helen

Margetts, ‘How Do People Feel about AI?’ (Ada Lovelace Institute and Alan Turing Institute, 2025) <https://attitudestoai.uk/findings-2025/benefits-and-concerns#7223> accessed 18 April 2025.

[32] Aidan Peppin, ‘The Citizens’ Biometrics Council: Recommendations and Findings of a Public Deliberation on Biometrics Technology, Policy and Governance’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2021) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/citizens-biometrics-council/> accessed 10 March 2025.

[33] Reema Patel and Aidan Peppin, ‘Making Visible the Invisible: What Public Engagement Uncovers about Privilege and Power in Data Systems’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 5 June 2020) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/blog/public-engagement-uncovers-privilege-and-power-in-data-systems/> accessed 23 April 2024.

[34] ibid.

[35] Octavia Field Reid, Anna Colom and Roshni Modhvadia, ‘What Do the Public Think about AI?’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2023) 11 <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/evidence-review/what-do-the-public-think-about-ai/> accessed 4 January 2025.

[36] Ada Lovelace Institute and Traverse, ‘Confidence in a Crisis? Building Public Trust in a Contact Tracing App’ (2020) 20 <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/confidence-in-crisis-building-public-trust-contact-tracing-app/> accessed 10 March 2025.

[37] Eleanor O’Keefe, ‘Making Good’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2025) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/ai-public-good/> accessed 23 April 2025.

[38] ibid.

[39] Roshni Modhvadia, ‘How Do People Feel about AI?’ (Ada Lovelace Institute and the Alan Turing Institute, 2023) 25 <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/public-attitudes-ai/> accessed 20 April 2025.

[40] Aidan Peppin, ‘Listening to the Public’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2023) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/listening-to-the-public/> accessed 13 June 2025.

[41] Aidan Peppin, ‘Listening to the Public’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2023) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/listening-to-the-public/> accessed 13 June 2025.

[42] Aidan Peppin, ‘Listening to the Public’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2023) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/listening-to-the-public/> accessed 13 June 2025.

[43] Roshni Modhvadia, Tvesha Sippy, Octavia Field Reid and Helen

Margetts, ‘How Do People Feel about AI?’ (Ada Lovelace Institute and Alan Turing Institute, 2025) <https://attitudestoai.uk/findings-2025/governance-and-regulation#71549 > accessed 18 April 2025.

[44] Understanding Patient Data and Ada Lovelace Institute, ‘Foundations of Fairness: Where next for NHS Health Data Partnerships?’ (Understanding Patient Data, March 2020) <https://understandingpatientdata.org.uk/sites/default/files/2020-03/Foundations%20of%20Fairness%20-%20Summary%20and%20Analysis.pdf> accessed 10 March.

[45] Harry Farmer, ‘Predicting: The Future of Health?’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2024) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/predicting-the-future-of-health/> accessed 29 April 2025.

[46] Aidan Peppin, ‘The Citizens’ Biometrics Council: Recommendations and Findings of a Public Deliberation on Biometrics Technology, Policy and Governance’ 32 (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2021) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/citizens-biometrics-council/> accessed 10 March 2025.

[47] Roshni Modhvadia, ‘How Do People Feel about AI?’ (Ada Lovelace Institute and the Alan Turing Institute, 2023) < https://attitudestoai.uk/findings-2023/understanding-trust-and-thoughts-about-regulation#19433 > accessed 18 April 2025.

[48] Eleanor O’Keefe, ‘Making Good’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2025) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/ai-public-good/> accessed 23 April 2025.

[49] Ada Lovelace Institute and Traverse, ‘Confidence in a Crisis? Building Public Trust in a Contact Tracing App’ (2020) 4 <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/confidence-in-crisis-building-public-trust-contact-tracing-app/> accessed 10 March 2025.

[50] Ada Lovelace Institute, ‘The Data Divide: Public Attitudes to Tackling Social and Health Inequalities in the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond’ (2021) 19 <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/The-data-divide_25March_final-1.pdf> accessed 11 November 2021.

[51] Octavia Field Reid, Anna Colom and Roshni Modhvadia, ‘What Do the Public Think about AI?’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2023) 16 <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/evidence-review/what-do-the-public-think-about-ai/> accessed 4 January 2025.

[52] Eleanor O’Keefe, ‘Making Good’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2025) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/ai-public-good/> accessed 23 April 2025.

[53] ibid.

[54] Anna Studman, ‘Access Denied? Socioeconomic Inequalities in Digital Health Services’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2023) 21 <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/healthcare-access-denied/> accessed 6 October 2023.

[55] Octavia Field Reid, Anna Colom and Roshni Modhvadia, ‘What Do the Public Think about AI?’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2023) 25 <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/evidence-review/what-do-the-public-think-about-ai/> accessed 4 January 2025.

[56] Roshni Modhvadia, Tvesha Sippy, Octavia Field Reid and Helen

Margetts, ‘How Do People Feel about AI?’ (Ada Lovelace Institute and the Alan Turing Institute, 2025) <https://attitudestoai.uk/> accessed 18 April 2025.

[57] Aidan Peppin, ‘The Rule of Trust: Findings from Citizens’ Juries on the Good Governance of Data in Pandemics’ (Ada Lovelace Institute 2022) < https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/trust-data-governance-pandemics/>

[58] Aidan Peppin, ‘The Citizens’ Biometrics Council: Recommendations and Findings of a Public Deliberation on Biometrics Technology, Policy and Governance’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2021) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/citizens-biometrics-council/> accessed 10 March 2025.

[59] Understanding Patient Data and Ada Lovelace Institute, ‘Foundations of Fairness: Where next for NHS Health Data Partnerships?’ 15 (Understanding Patient Data, March 2020) <https://understandingpatientdata.org.uk/sites/default/files/2020-03/Foundations%20of%20Fairness%20-%20Summary%20and%20Analysis.pdf> accessed 10 March.

[60] Understanding Patient Data and Ada Lovelace Institute, ‘Foundations of Fairness: Where next for NHS Health Data Partnerships?’ 13 (Understanding Patient Data, March 2020) <https://understandingpatientdata.org.uk/sites/default/files/2020-03/Foundations%20of%20Fairness%20-%20Summary%20and%20Analysis.pdf> accessed 10 March.

[61] Aidan Peppin, ‘The Citizens’ Biometrics Council: Recommendations and Findings of a Public Deliberation on Biometrics Technology, Policy and Governance’ 32 (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2021) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/citizens-biometrics-council/> accessed 10 March 2025.

[62] Octavia Field Reid, Anna Colom and Roshni Modhvadia, ‘What Do the Public Think about AI?’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2023) 19 <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/evidence-review/what-do-the-public-think-about-ai/> accessed 4 January 2025.

[63] Aidan Peppin, ‘The Rule of Trust: Findings from Citizens’ Juries on the Good Governance of Data in Pandemics’ (Ada Lovelace Institute 2022) 41 < https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/trust-data-governance-pandemics/>

[64] Roshni Modhvadia, ‘How Do People Feel about AI?’ (Ada Lovelace Institute and the Alan Turing Institute, 2023) 25 <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/public-attitudes-ai/> accessed 20 April 2025.

[65] Roshni Modhvadia, Tvesha Sippy, Octavia Field Reid and Helen

Margetts, ‘How Do People Feel about AI?’ (Ada Lovelace Institute and the Alan Turing Institute, 2025) <https://attitudestoai.uk/> accessed 18 April 2025.

[66] ‘Information on how AI systems made a decision about you’ was not included as an option in the 2023 survey.

[67] Roshni Modhvadia, Tvesha Sippy, Octavia Field Reid and Helen

Margetts, ‘How Do People Feel about AI?’ (Ada Lovelace Institute and the Alan Turing Institute, 2025) < https://attitudestoai.uk/findings-2025/governance-and-regulation#78888> accessed 18 April 2025.

[68] Octavia Field Reid, Anna Colom and Roshni Modhvadia, ‘What Do the Public Think about AI?’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2023) 25 <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/evidence-review/what-do-the-public-think-about-ai/> accessed 4 January 2025.

[69] Roshni Modhvadia, Tvesha Sippy, Octavia Field Reid and Helen

Margetts, ‘How Do People Feel about AI?’ (Ada Lovelace Institute and the Alan Turing Institute, 2025) <https://attitudestoai.uk/findings-2025/governance-and-regulation#66464> accessed 18 April 2025.

[70] Understanding Patient Data and Ada Lovelace Institute, ‘Foundations of Fairness: Where next for NHS Health Data Partnerships?’ 15 (Understanding Patient Data, March 2020) <https://understandingpatientdata.org.uk/sites/default/files/2020-03/Foundations%20of%20Fairness%20-%20Summary%20and%20Analysis.pdf> accessed 10 March.

[71] Aidan Peppin, ‘The Citizens’ Biometrics Council: Recommendations and Findings of a Public Deliberation on Biometrics Technology, Policy and Governance’ 22 (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2021) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/citizens-biometrics-council/> accessed 10 March 2025.

[72] Aidan Peppin, ‘Listening to the Public’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2023) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/listening-to-the-public/> accessed 13 June 2025.

[73] Eleanor O’Keefe, ‘Making Good’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2025) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/ai-public-good/> accessed 23 April 2025.

[74] Octavia Field Reid, Anna Colom and Roshni Modhvadia, ‘What Do the Public Think about AI?’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2023) 27 <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/evidence-review/what-do-the-public-think-about-ai/> accessed 4 January 2025.; Roshni Modhvadia, Tvesha Sippy, Octavia Field Reid and Helen

Margetts, ‘How Do People Feel about AI?’ (Ada Lovelace Institute and the Alan Turing Institute, 2025) < https://attitudestoai.uk/findings-2025/benefits-and-concerns#72304> accessed 18 April 2025.

[75] Reema Patel and Aidan Peppin, ‘Making Visible the Invisible: What Public Engagement Uncovers about Privilege and Power in Data Systems’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 5 June 2020) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/blog/public-engagement-uncovers-privilege-and-power-in-data-systems/> accessed 23 April 2024.

[76] Aidan Peppin, ‘The Rule of Trust: Findings from Citizens’ Juries on the Good Governance of Data in Pandemics’ (Ada Lovelace Institute 2022) < https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/trust-data-governance-pandemics/>

[77] Understanding Patient Data and Ada Lovelace Institute, ‘Foundations of Fairness: Where next for NHS Health Data Partnerships?’ 19 (Understanding Patient Data, March 2020) <https://understandingpatientdata.org.uk/sites/default/files/2020-03/Foundations%20of%20Fairness%20-%20Summary%20and%20Analysis.pdf> accessed 10 March.

[78] Octavia Field Reid, Anna Colom and Roshni Modhvadia, ‘What Do the Public Think about AI?’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2023) 27 <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/evidence-review/what-do-the-public-think-about-ai/> accessed 4 January 2025. Also in ‘Listening to the Public’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2023) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/listening-to-the-public/> accessed 13 June 2025.

[79] Aidan Peppin, ‘Listening to the Public’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2023) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/listening-to-the-public/> accessed 13 June 2025.

[80] Octavia Field Reid, Anna Colom and Roshni Modhvadia, ‘What Do the Public Think about AI?’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2023) 21 <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/evidence-review/what-do-the-public-think-about-ai/> accessed 4 January 2025.; O’Keefe (n 20).

[81] Octavia Field Reid, Anna Colom and Roshni Modhvadia, ‘What Do the Public Think about AI?’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2023) 17 <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/evidence-review/what-do-the-public-think-about-ai/> accessed 4 January 2025.

[82] Aidan Peppin, ‘The Rule of Trust: Findings from Citizens’ Juries on the Good Governance of Data in Pandemics’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2022) 41 <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/trust-data-governance-pandemics/>

[83] ibid.

[84] Aidan Peppin, ‘Listening to the Public’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2023) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/listening-to-the-public/> accessed 13 June 2025.

[85] Harry Farmer, ‘Predicting: The Future of Health?’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2024) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/predicting-the-future-of-health/> accessed 29 April 2025.

[86] Eleanor O’Keefe, ‘Making Good’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2025) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/ai-public-good/> accessed 23 April 2025.

[87] ibid.

[88] Understanding Patient Data and Ada Lovelace Institute, ‘Foundations of Fairness: Where next for NHS Health Data Partnerships?’ 11 (Understanding Patient Data, March 2020) <https://understandingpatientdata.org.uk/sites/default/files/2020-03/Foundations%20of%20Fairness%20-%20Summary%20and%20Analysis.pdf> accessed 10 March.

[89] Eleanor O’Keeffe, ‘Making Good’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2025) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/ai-public-good/> accessed 23 April 2025.

[90] Elliot Jones and Imogen Parker, ‘Building blocks: four recommendations to strengthen the foundations for AI in the public sector’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2025) <https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/blog/four-recommendations-strengthen-ai-public-sector/> accessed 1 June 2025.

Image credit: georgeclerk

Related content

Learn fast and build things

Lessons from six years of studying AI in the public sector