Risky business

An analysis of the current challenges and opportunities for AI liability in the UK

Reading time: 177 minutes

How to read this paper

- If you are a policymaker or regulator working on AI more generally, read the ‘Executive summary’ that provides an overview of why liability for AI in the UK is currently not working as it should. It points to seven challenges and potential routes to addressing them.

- If you are a policymaker or regulator specifically thinking about AI liability, read ‘The current situation’, which explains the current situation for AI liability in the UK by describing how contracts redistribute liability risk, how liability risk is perceived by UK companies, and includes illustrative examples.For a deeper understanding of the challenges in non-contractual liability for AI and suggestions for areas of policy development, read the sections that discuss the challenges for AI liability in depth, from ‘Establishing a breach of the duty of care’ to ‘Unfair contractual clauses’.

- If you are a legal professional or (legal) researcher, read the sections that discuss the challenges for AI liability in depth (from ‘Establishing a breach of the duty of care’ to ‘Unfair contractual clauses’) for an analysis of legal challenges that AI poses for non-contractual liability.

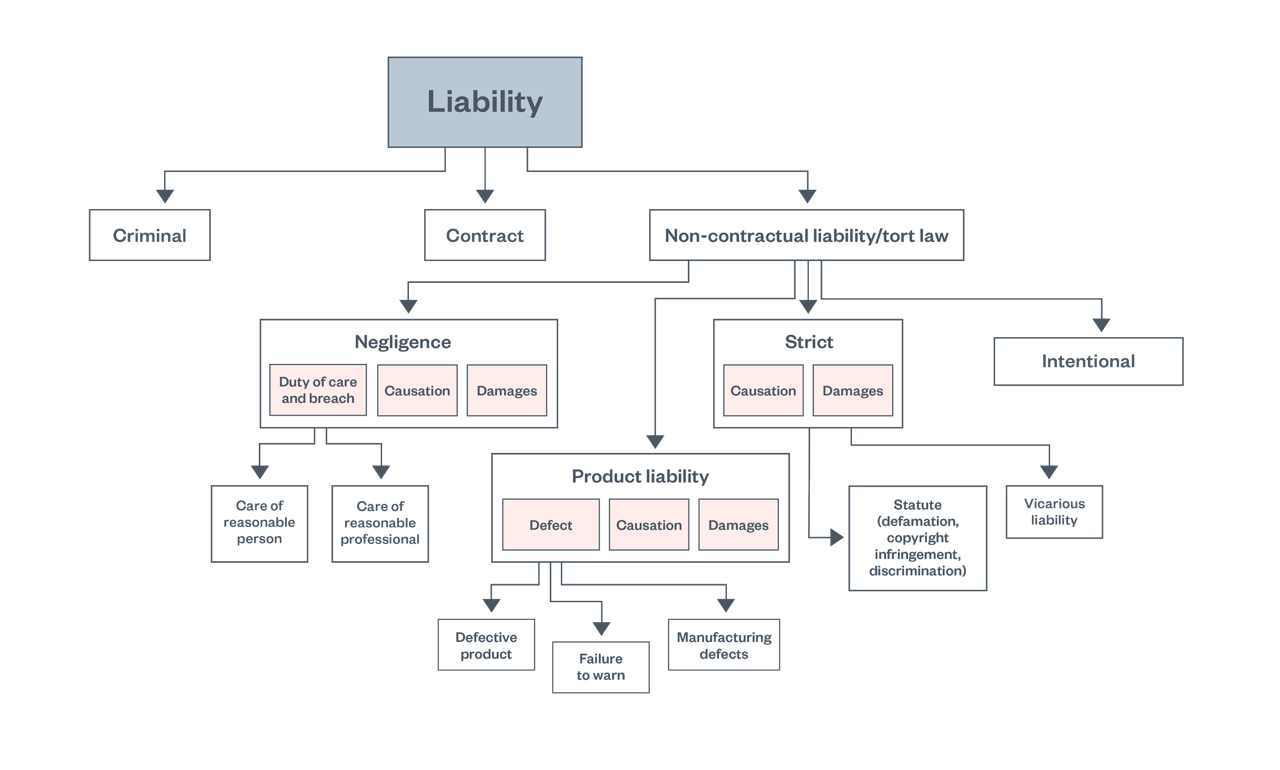

- If you are a reader without a strong legal background (or who wants to refresh their understanding of non-contractual liability), refer to the ‘Appendix’. This includes an extensive overview of what non-contractual liability is; the main forms it comes in (fault-based, strict, product liability, vicarious liability); an in-depth exploration of relevant legal elements (causation, damages); and the interplay between non-contractual liability and insurance, and non-contractual liability and contracts.

The Appendix also includes an ‘Overview of relevant legislation and legislative proposals’ related to AI liability that are ongoing at the time of publication of this paper and relevant to keep an eye on.

Executive summary

This paper focuses on civil liability for AI in (mainly) the UK, although many of the core findings will be relevant for other jurisdictions. Liability refers to the legal responsibility that someone has for their actions or omissions. This paper in particular focuses on contractual and non-contractual liability.

Clear liability laws can provide a route to redress for parties harmed by AI systems, create incentives for risk management and prevention, and help clarify legal risks for people and organisations who develop or use AI.

Currently in the UK, pre-existing liability rules are not sufficient to achieve these aims, meaning a fundamental incentive to ensure AI risk is managed effectively and distributed fairly is broken. In the context of wide-scale adoption of general-purpose AI systems across public services and the economy, the impact is that unmanaged legal and financial risk is loaded onto downstream deployers of AI, such as local authorities and small businesses.

These downstream deployers have few effective means of addressing these risks and the resulting harms can affect their products, services and the people who use them. There is also an absence of any meaningful mechanism for deployers to seek redress.

The findings of this paper are based on a legal analysis, an expert roundtable, further expert input and desk research. The paper finds:

- The liability system is too burdensome on people or organisations harmed by AI systems, who will struggle to obtain sufficient evidence and prove fault and causation in AI contexts. This inhibits the incentivising effect of liability law in encouraging risk management at the point that risk arises.

- Contract terms are used to shield large corporate AI actors from liability risk, who instead push risk down to smaller actors (people or companies) lower in the value chain.

- Companies are not always aware of their risk exposure from AI use or have some awareness but deploy AI regardless. Many AI adopters are (inadvertently) taking on large or unclear liability risks, in many instances out of fear of falling behind their competition.

- Pre-existing liability rules are not always fit to neatly deal with challenges introduced by AI systems, such as their opacity, unpredictability, autonomous capabilities and their propensity to cause immaterial or systemic harms. This means liability law will fail to encourage the management of non-material risks (such as impacts on mental health or the environment).

This paper sets out these challenges in more detail and, where appropriate, provides pathways and considerations for addressing these issues. Liability for AI is complex and there is not one ‘easy fix’ to make the UK’s liability system fit for AI. Instead, we lay out different policy routes and complementary measures that policymakers can explore to address AI liability challenges. This paper points to:

1. Challenges with establishing a breach of the duty of care, as the newness of AI technologies means there is not yet a clear established ‘standard of care’ that sets expectations on the type of safety precautions that AI companies should be taking.

- Promoting the development of safety practices through legal rules, AI safety research, standards and assurance can help push towards the crystallisation of a standard of care.

- Strict liability can be a solution in particularly hazardous situations.

- Professionalisation of AI occupations can help formalise a professional standard of care that AI engineers can be held to.

2. Challenges relating to agentic and autonomous capabilities, as this raises questions about the allocation of responsibility where AI systems have acted outside of the realm of effective control of a user.

- Taxonomising agents based on their capabilities can clarify who can exercise control in different scenarios, and what control looks like in that context.

- Agent IDs and other agent visibility measures will be necessary to identify if the responsible party in an accident is an AI agent, and who that AI agent is acting on the behalf of.

- Vicarious liability and legal personhood are legal routes that have been proposed by some authors as ways to hold the relevant actors liable in AI agent contexts, although these approaches face practical and legal hurdles.

3. Challenges relating to complex value chains and opacity which can confound proving causation in AI contexts.

- Solutions such as joint and several liability can assist in cases where multiple actors contributed to a final harmful outcome.

- Measures that facilitate transparency and mandate disclosure of evidence or reversals of the burden of proof (in limited contexts) can ease the burden on claimants.

4. Challenges relating to open-source AI, as publishing software as open source will sever the control a developer has over subsequent developers and uses of that software.

- Platforms for developing and running open-source AI models can play a larger role in obtaining relevant information about the specifics of a model before uploading it, and removing problematic AI models from their platforms.

5. Challenges relating to unpredictability and lack of foreseeability, as the inherent predictive nature of new AI models makes it more complex to foresee how an AI system will act and what potential damages it could create down the line.

- Documenting incidents of AI harms in databases can clarify the range of harms and risks associated with different AI systems, making them more easily predictable.

- Human-computer interaction (HCI) research can help clarify how users are likely to interact with an AI product, thereby supporting the development of technical measures to support human oversight.

6. Challenges relating to types of damages, as AI systems are more likely to cause immaterial damages such as violations to human rights or pure economic loss, or cause damages that are only noticeable at a systemic level.

- Allowing for (limited) immaterial damages in AI cases can support claimants in obtaining redress for a wider scope of harms.

- Collective redress can ease the burden on claimants and make it easier to obtain redress for smaller damages that affect a large group of people.

7. Challenges relating to unfair contractual clauses, as these can have a significant impact on the distribution of liability and shield some actors from liability risk.

- Updating legislation on unfair contractual terms and clarifying their application in an AI context can support smaller developers and deployers of AI who face contractual relations with powerful AI vendors.

- Structures for pre-market approval could include approval of the standard terms and conditions under which the product is offered.

Policymakers will need to take steps to address these challenges to prevent the costs of AI harms from fully landing with downstream developers and users, who may not have the capacity to take appropriate measures to protect themselves and others from AI harms.

Liability is a key legal mechanism to catch and help prevent the negative consequences from AI, but its pre-existing legal norms in the UK are too burdensome on affected people and too unclear for companies to know how to navigate AI risk in the context of a rapidly evolving technology.

Introduction

Liability refers to the legal responsibility that a person or company has for their actions or omissions. In the past few years of the ‘AI boom’, the harms caused by AI systems have repeatedly attracted media attention. These harms range from autonomous car crashes and biased recruitment tools to mental health impacts from prolonged engagement with AI chatbots. Such cases raise the question of who, if anyone, will and should be held responsible for such harms.

Some high-profile cases relating to AI liability have similarly made headlines, however these cases tend to be in other jurisdictions (such as the US) and venture into unexplored legal territory, carrying large amounts of legal uncertainty. Bringing a liability case for an AI harm is complex, uncertain and can be very burdensome on claimants. As a result, people may struggle to see their damages compensated by the responsible party.

At the same time, people and companies may not always know what kind of liability risk they may be exposing themselves to by using an AI system in their personal life or in their business.

Liability may arise from various sources of law, such as criminal law, contract law and non-contractual liability (also known as ‘tort law’ in common law countries). This paper mainly focuses on civil liability: how contracts and non-contractual liability impact on the distribution of liability risk and people’s ability to obtain compensation when they have been harmed. It explores how the current contract and non-contractual liability may apply to AI, and the challenges in that context.

Although there are varied perspectives on the ‘purpose’ of a liability system, this paper considers three broad aims when thinking about AI liability from a UK policy standpoint:[1]

- Redress: Allow affected people and organisations a clear path to legal recourse when they have been harmed, so that the cost of the harm is moved from the affected party to the party responsible for the harm.

- Proper risk distribution and safety incentives: Place the burden of liability with the actor(s) best situated to prevent harm from materialising to create a socially optimal allocation of risk, so that they will be incentivised to prevent harms from happening. Legal responsibility should not be unfairly pushed away from some actors and onto others.

- Regulatory clarity: Reduce uncertainty about legal risk for people and organisations who develop or use AI, ensuring it does not inhibit appropriate adoption.

Non-contractual liability is a key piece of the AI governance puzzle to ensure that AI is safe, effective and accountable. It provides people and businesses with a course of action besides regulatory scrutiny. It may complement forms of risk reduction that are aimed at making AI products safe before they hit the market (ex ante), such as developing reliable methods for AI evaluations and a strong third party assurance regime.[2]

Still, such methods will not be able to prevent all AI harms from materialising. A clear liability regime can play an important role in providing remedies after AI systems are launched on the market (ex post) and instilling trust that AI users will be adequately compensated if an AI product does cause harm, which may increase public trust in AI overall.[3]

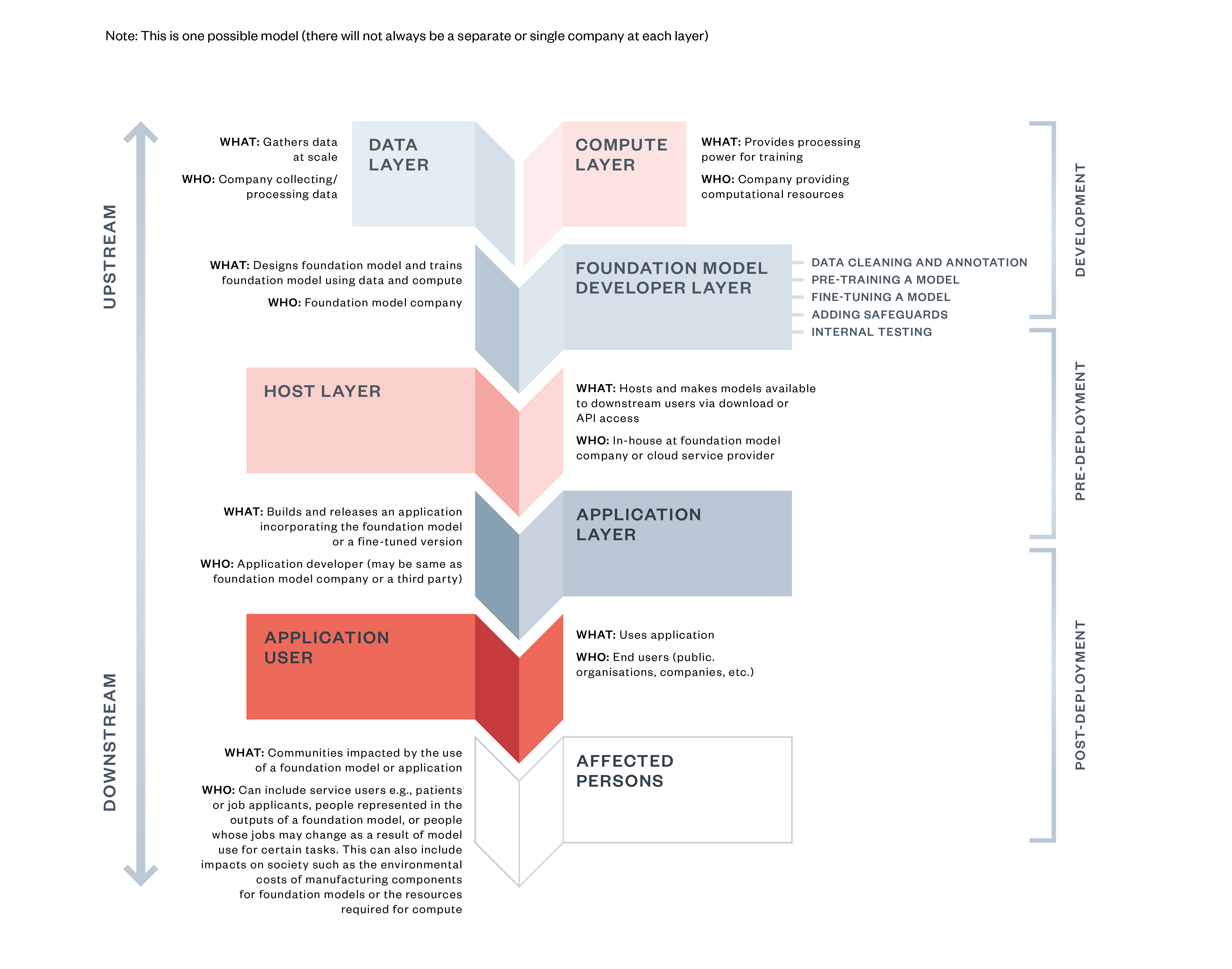

At the moment, the objectives of redress, risk distribution and legal clarity stated above are not fully realisable under current UK law. Contracts impact on the allocation of risk between actors among the value chain, shielding larger actors, like upstream AI developers, from liability risk, while disproportionately pushing the risk towards smaller actors with less negotiating power.

Where it is possible to bring liability cases and obtain legal recourse through non-contractual liability, claimants are faced with challenges in bringing successful claims.[4]

Such challenges include:

- Complex value chains and opacity: As there are ‘many hands’ that contribute to the development and deployment of an AI system, it can be complex to pin down what actor(s) in the value chain can be held liable for an AI system that caused harm.

- Unclear standard of care: If potential liable actors have been identified, it can be challenging to establish if and how their behaviour falls short of the reasonable precautions they should have taken, as the standard of care for AI developers is not clear.

- Autonomous and agentic capabilities: As AI systems become more autonomous, both in decision-making and their actions, this may create a barrier to effectively controlling the behaviour of an AI system, which raises questions about who to hold liable when an autonomous AI system causes harm.

- Open source: AI systems themselves or their underlying models can be published open source, which means that their developers no longer have any control over their use and functioning after they have been published. This raises questions about how responsibility for (partially) open-source AI systems should be attributed.

- Unpredictability: LLM-based AI systems are fundamentally unpredictable, which raises questions about how to establish the reasonable foreseeability of certain harms.

- Limited coverage of immaterial or systemic harms: The main routes within non-contractual liability (product liability and negligence) primarily – though not solely – cover personal injury and property damage, making more immaterial harms difficult to cover within existing legal pathways.

This paper explores how contracts between actors in the AI value chain and challenges in bringing legal cases can impact the distribution of liability risk and people’s ability to access redress when they have suffered harm due to an AI system.

The findings of this paper are based on an extensive literature review, a roundtable with UK lawyers and legal experts, and a review by UK lawyers with domain expertise. It aims to describe the current situation for civil liability in the UK with regard to AI harms, as well as lay out a range of options for addressing some of the challenges within that system.

List of abbreviations and legal terminology used in this paper

Tort

A wrongful act that forms a ground to hold actors legally liable under non-contractual liability

Tortfeasor

The actor (person or company) that commits a legally wrongful act

Externality

A secondary, unintended impact of an activity

LLM

Large language model

EHRC

Equality and Human Rights Commission

ICO

Information Commissioner’s Office

FCA

Financial Conduct Authority

CPA 1987

Consumer Protection Act 1987

CRA 2015

Consumer Rights Act 2015

EU PLD

European Union’s Product Liability Directive

UCTA 1977

Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977

AILD Proposal

European Union’s Artificial Intelligence Liability Directive proposal

The basics: what is non-contractual liability for?

Non-contractual or tort liability can enable people and organisations to obtain redress and ensure that actors responsible for damages are held accountable. For people and organisations, non-contractual liability is a route through which they can be compensated if they incur damages because of an AI system. For deployers and developers, the risk of being sued for damages resulting from their AI system may incentivise them to invest more in preventative measures.

Non-contractual liability is situated within a wider body of regulatory and non-regulatory mechanisms that aims to incentivise societally desirable behaviour and discourage negative behaviours. Besides laws, behaviours can also be guided through market-based incentives, such as due diligence requirements, procurement guidelines, licensing regimes, insurance and effective competition between competitors.[5]

Non-contractual liability is not the only ‘carrot or stick’ approach through which behaviour can be guided, but it supplements and interacts with other forms of liability that may be applicable to AI – such as contractual liability – and these ‘softer’ market incentives.

Although this paper focuses on non-contractual liability, it also touches on other regimes that interact with non-contractual liability and may impact the effectiveness of a non-contractual liability regime.

Rationales for imposing non-contractual liability

As stated in the introduction, liability can help people and companies obtain compensation for damages that they have incurred due to an AI system under certain circumstances.

Liability can also help incentivise actors, such as AI companies, to act with appropriate caution when developing or deploying AI systems. But there are several underlying rationales to keep in mind when considering what the ‘best’ way of allocating non-contractual liability looks like. These rationales can be roughly divided into justice and economic considerations.

Firstly, non-contractual liability is linked to ‘corrective justice’ theories. Corrective justice concerns itself with the gains and losses that one person or company may cause another – it seems unjust that someone may benefit from committing a wrong and thereby cause a loss to someone else or move the risk for that loss to another actor.[6]

Non-contractual liability is therefore also focused on ‘making the victim whole again’ after they have suffered a loss through a wrong committed by someone else, usually through means of financial compensation and a commitment to preventing similar wrongs from happening again.[7] Non-contractual liability is the legal expression of the idea that people in society have a certain normative relationship to each other, and therefore should exercise appropriate care.

Secondly, from an economic point of view, non-contractual liability is a way to push people and organisations to consider the potential negative side effects caused by their activities.[8] For example, if you know your AI system sometimes states inaccurate information and that you can be sued if such inaccurate information causes harm to someone, then you will likely have a stronger reason to make your AI system more accurate or place appropriate warnings. Taking precautions is beneficial as it may lessen your liability exposure.

If the liability burden is placed with the right actors, this will incentivise them to take an economically efficient amount of precaution, where the cost is still lower than the costs of being sued and having to compensate for damage to the affected people.[9] This relates to theories about deterrence, where ensuring that the right people and organisations are held liable will deter them from taking unreasonably risky actions.

Within deterrence theories, actors that can contribute to increasing or decreasing the risk of harm through their conduct (including developers and users of goods and services) should bear some part of the liability burden to prevent moral hazard.[10]

Moral hazard occurs when an actor fails to take appropriate care as they know they will not be liable for ensuing harms. For example, prior to the 2008 financial crisis, some major banks acted more recklessly because they knew they would be ‘bailed out’ by the government if they were at risk of going bust.[11]

Contracts and non-contractual liability

Non-contractual liability rules apply to people and organisations regardless of whether or not they agree to them. In contrast, contracts and ensuing legal responsibilities are entered into voluntarily by actors when they sign a contract. As long as the contractual provisions are not against the law, they can also cap liability at a certain amount or include provisions on ‘indemnities’. An indemnity is when one party is required to compensate another party when they incur a loss.

For example, some AI companies state that they will compensate users that are held liable for copyright infringement. The liability does not ‘change’: the user is still liable, but they are compensated by the AI company.[12] The report section on ‘Impact of contracts on liability in the UK’ will address in more depth how contracts are currently used in the UK to change and impact the distribution of AI liability risks.

Private governance

This paper rests on the assumption that the non-contractual liability system is an appropriate route to properly placing incentives for safe behaviour and providing effective routes for redress for individuals, as a complement to regulatory action. There are other authors who support purely market-based solutions and private governance.[13]

Private governance typically refers to governance by non-government organisations, such as assurance or insurance companies. This paper does not preclude that such private governance approaches may complement a non-contractual liability regime; in fact, this paper describes how insurance can work in tandem with non-contractual liability in some situations (see the section on ‘Insurance’ in the Appendix) and suggests that standards developed by standardisation bodies can help establish the level of care that should be exercised by a tech company (see the section on ‘Establishing a breach of the duty of care’).

However, unless paired with binding regulation, private governance systems are voluntary and not necessarily paired with fines in case of non-compliance. Non-contractual liability can thus provide a stronger consequence in case of harm. Although the non-contractual liability system can be slow and expensive to navigate, it has emerged over decades of precedent and statute and has adapted to meet the demands of previous periods technological change, such as the industrial revolution and the emergence of cars, trains and railways.

Courts in the United States have allowed non-contractual liability cases regarding automated vehicles and chatbots to proceed, signalling that pre-existing liability rules can conceivably be applied to newer technologies.[14]

Still, issuing legal guidance that clarifies how exactly these rules apply in such new contexts would give claimants more certainty, and would be preferable to having to wait for (slow) court processes and judgments to come through. Policymaker intervention is welcome and needed in this space to ensure legal certainty and redress for affected people and organisations.

Non-contractual liability provides a flexible ‘catch-all’ type of redress, with negligence applying to AI companies even in the absence of new AI regulation or private governance structures. As discussed, non-contractual liability sits within a complex system of other forms of liability (contracts, criminal), private governance and regulation. All these instruments used together can push towards safe and accountable AI.

Non-contractual liability is just one piece of the puzzle: it allows affected people to still have access to a legally binding form of redress when regulation is absent (or regulators are ineffective) and when voluntary mechanisms prove insufficient to hold companies accountable.

The current situation

Widespread AI use is still relatively new. The technology has advanced in recent years, creating new use cases and potential risks to people and society. While AI liability cases will likely still take time to make their way through the courts, there are open questions on how liability risk is currently distributed between actors in the AI value chain and what obstacles may arise for people and organisations wanting to obtain redress for AI harms.

We conducted a roundtable with lawyers and legal experts in the UK to obtain evidence on what the current landscape for AI liability risk looks like.

AI liability risk and risk appetite in the UK

UK lawyers stated a range of AI liability risks that are front of mind for businesses in the UK. The risks considered by companies will be sector- and use case-specific, but generally include the risks outlined below.

Intellectual Property (copyright infringement, database rights)

| Example | Type of liability | Other routes to redress (regulatory action) |

| AI model provider copies and then trains an AI model on copyrighted data without legislative exemption or the output of the model is too similar to copyrighted material. | Copyright infringement is a strict liability tort in the UK. | For small claims (under £10,000) a complaint can be lodged with the Intellectual Property Enterprise Court.[15] |

Data protection infringement

| Example | Type of liability | Other routes to redress (regulatory action) |

| An employee shares personal data of clients with a chatbot from an external AI company and does so without a lawful basis. | Misuse of private information is a strict liability tort in the UK.

|

There is also a non-civil liability route to redress, by making a complaint to the UK’s data protection authority, the ICO. |

Third-party liability (personal injury, property damage, economic loss)

| Example | Type of liability | Other routes to redress (regulatory action) |

| Any injury or damage to a ‘third party’ (i.e. a bystander, not the user or developer): a self-driving car injures a pedestrian or damages someone’s property; AI involved in clinical decision-making recommends the wrong treatment, leading to a patient’s injury. | Most likely negligence (professional), but occasionally strict liability if in a regulated sector (self-driving cars) or product liability. | Potential routes to make complaints to regulators or supervisory bodies if the incident occurs in a regulated sector (e.g. General Medical Council for a healthcare worker using AI). |

Liability stemming from non-compliance with sector-specific or AI regulation

| Example | Type of liability | Other routes to redress (regulatory action) |

| A company uses a type of AI that is prohibited through AI regulation (such as an emotion recognition system in the workplace under the EU AI Act). | Potentially strict liability based on regulatory breach, but would require parliamentary intent favouring strict liability. | Potential routes to make complaints to the regulator supervising the enforcement of the breached regulation, such as the FCA for financial services. |

Liability due to discrimination

| Example | Type of liability | Other routes to redress (regulatory action) |

| A company uses an AI tool that discriminates against protected groups in recruitment or credit scoring contexts. | Statutory liability for discrimination;[16] vicarious liability (employer responsible for employee/ contractor). | Make a complaint to the Equality and Human Rights Commission. |

Breach of contract

| Example | Type of liability | Other routes to redress (regulatory action) |

| Contract contains a clause that prohibits the use of AI for the fulfilment of the contract, but an employee or subsidiary does use AI in the course of performing the contract. | Contractual liability, subject to the conditions stipulated in the contract. | N/A |

It should be noted that these are the some of the main areas of concern for UK companies that were shared during the roundtable, but may not cover all possible liability risks for UK businesses and individual consumers.

As can be seen in the tables above, for many of the strict and fault-based non-contractual liability grounds, there are also routes to redress via a regulatory body (such as the ICO or EHRC).

However, these regulatory bodies usually cannot award financial compensation to an affected person in response to a complaint. Additionally, regulators are not always well resourced enough to respond in a timely manner to (all) lodged complaints.

The route to civil liability is therefore a helpful complementary route to enable people to claim compensation. It is generally allowed for an affected person to simultaneously lodge a complaint with a regulator and to sue someone in court for the losses they have incurred.

Despite these risks being present, experts at the roundtable agreed that there was still a large appetite for AI purchases and adoption in the UK market. Concerns about liability exposure did not outweigh fears within businesses of ‘missing out’ on a new technology or lagging behind competitors.

Companies therefore proceed with AI adoption either in spite of known liability risks, or because they are not fully aware of them. Either way, this can lead to situations where companies are faced with higher liability exposure than anticipated, and few commercial pathways to shifting it.

An exception to this, according to roundtable participants, are regulated sectors such as financial services or companies delivering aspects of public services, requiring them to be compliant with certain public sector requirements. These companies showed more hesitancy and concern in AI adoption due to potential liability risks.

Impact of contracts on liability in the UK

Liability burdens can be placed with certain actors for economic and justice reasons, but actors can privately reallocate how liability burdens are distributed through contractual clauses. This use of contracts to distribute liability is called ‘private ordering’.[17]

Especially in the context of large AI providers, contracts often take the shape of standard terms and services, both for business-to-consumer (B2C) and business-to-business (B2B) customers. According to lawyers consulted for this paper, even larger companies are usually presented with standard terms of use when adopting products directly from large AI providers.

As will be explained in the section ‘Overview of relevant legislation in the UK and EU’ below, AI can be offered as a product or as a service. In the EU, both are covered under the (updated) EU product liability directive and other EU consumer protection legislation respectively.

In the UK, AI will only be seen as a ‘product’ in limited circumstances (when embedded in a tangible good) and as a service or ‘digital content’ in most other cases.[18] Where AI is provided as a service there will always be some kind of contract or standard terms and services that apply.

Also, there will be a contractual basis for most AI software-as-product situations. This means that contracts play a big role in the potential (re)distribution of liability for AI products and services.

Contracts can impact on risk distribution for AI harms in three main ways:

- Contracts may set the standard for what non-performance of the contract means. For example, if a contract focuses on the sale of a car, then the contract can be considered to be breached or not performed if the car is against the specifications agreed in the contract when delivered (for example, it is broken or the wrong colour). For generative AI, defects may be more difficult to prove as a chatbot that ‘hallucinates’ is not necessarily considered defective, but contracts can still set out certain requirements that a contracted AI system needs to meet.[19] Contracts may also set limitations for the period within which non-performance of the contract can be claimed.

- Contracts may rebut presumptions under non-contractual liability. For example, if an artist creates a piece of art and a tech company uses it without their consent, then the artist could sue them for copyright infringement (which is a tort subject to strict liability in the UK). However, if the artist and the tech company have a contract in place that gives the company a licence to use the artist’s art, then there are no copyright infringements and no grounds to claim non-contractual liability.

- Contracts may contain provisions on limitations of non-contractual liability. Usually, contracts between a software or data provider and a customer contain a liability clause that caps the maximum liability that the provider can be required to pay. For example, a contract may contain a clause that states that if an AI system causes some kind of harm, the provider will only compensate the customer up to a certain amount of money. If the actual damages are higher than the liability cap, then the customer themselves will have to absorb the loss for the leftover amount.

Example: Liability cap in terms of use

OpenAI’s business terms of use contains a clause that limits OpenAI’s liability.[20] OpenAI states that if damages occur during the use of an OpenAI product (like ChatGPT) by a business, OpenAI will only carry liability for ‘the amount you paid for the service that gave rise to the claim during the 12 months before the liability arose or one hundred dollars ($100)’.

If a loss occurs that is higher than what the business has paid for the OpenAI product in the past year, then the leftover amount must be paid by the business themselves.

Contracts will be in place between all different actors in the AI value chain. Businesses are usually, at least in theory, able to negotiate the terms of the contract through which they obtain a licence to use an AI system. This will include negotiating about limitations or exclusions of liability.

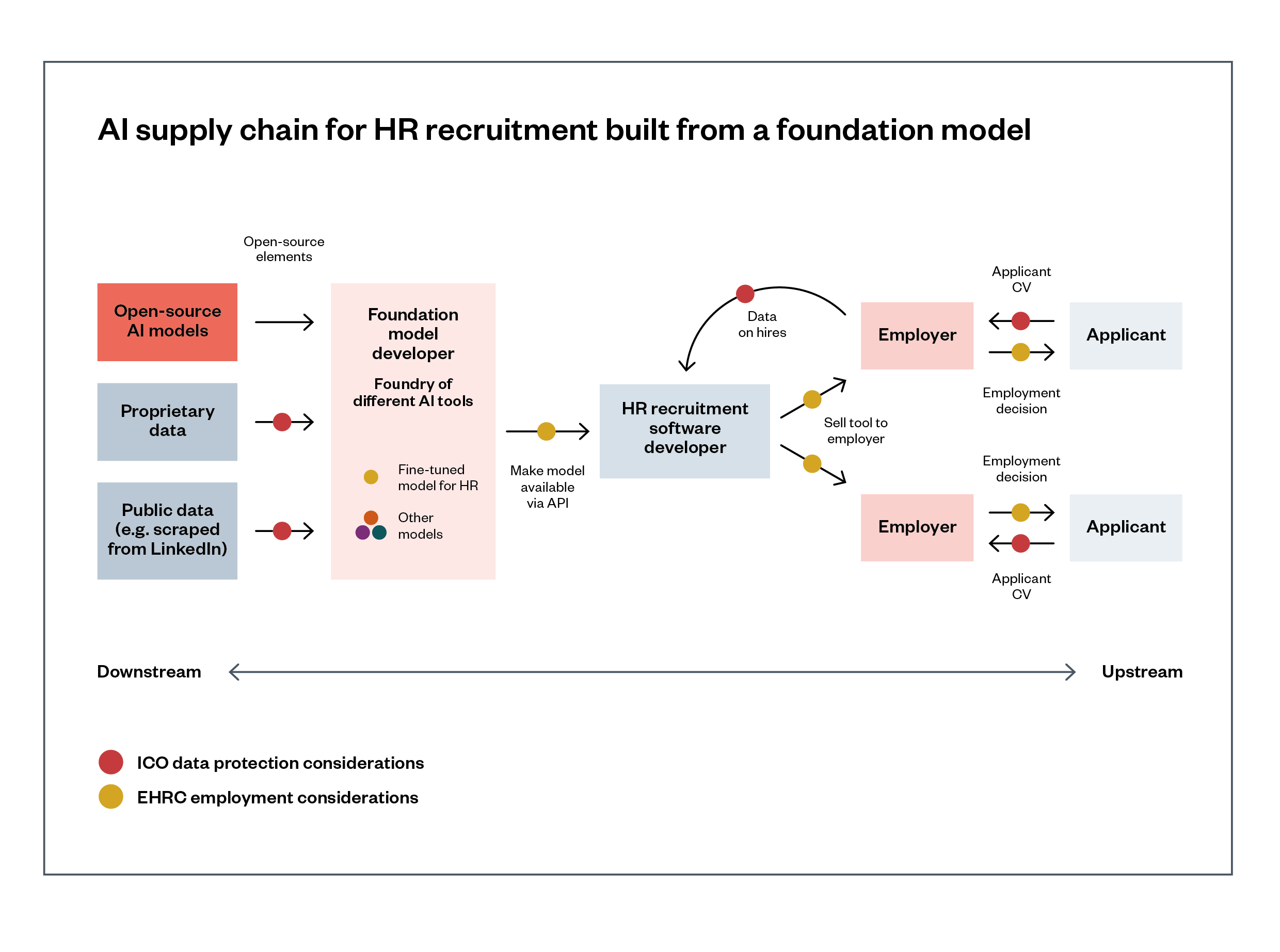

Figure 1: Example of an AI supply chain for a recruitment tool

However, legal experts that were consulted during the roundtable to inform this paper stated that in practice almost all business clients do not have a strong position in contract negotiations with big tech companies and often have to settle for standard terms of use.

A business has a slightly better chance at negotiating with tech companies if they have a larger spend or are subject to legal requirements, such as public sector duties if it is a government client. However, most businesses are faced with standard contractual clauses that shift liability risks away from large AI model vendors.

The legal experts consulted for this research expressed that they see a tendency in contracts to distribute liability away from large AI model providers and move it down the value chain.

Legal experts further expressed that if the final buyer of the AI system (usually the downstream deployer) is also a large actor, this may lead to a ‘squeeze’ of smaller AI companies that may find themselves positioned between the model developer and large downstream deployers.

Neither the model developer nor the deployer will accept liability, so this leads to mainly SMEs in the middle of the value chain carrying liability burdens.

Overview of relevant legislation in the UK and EU

Both in the UK and the EU there are various pieces of relevant legislation that apply to AI systems. AI systems may be offered as a product or as a service. A product usually means that there is a form of transfer of ownership without further engagement with the seller, while a service implies there is an ongoing relationship with the seller (e.g. for maintenance or updates).

This section first provides an overview of the ways in which AI may be sold (as a product, service or digital content) and which relevant regulations apply in the UK and EU. We then provide three example scenarios (a chatbot giving wrong information, an automated vehicle crash and discriminatory hiring), which we discuss in detail to show where gaps arise in the current liability system in the UK.

The gaps identified are summarised into seven challenges for AI liability that will be discussed in the next section.

For more explanation, the section on ‘Contracts and liability’ in the Appendix sets out the different legislations in these tables in more detail.

AI as a product / good

| In the UK | Relevant regulation | |

| AI will mostly not be considered as a ‘good’ but may be if it is supplied on physical hardware (e.g. on a USB) or potentially if it is embedded in a physical object (e.g. a smart device).[21] |

|

|

| In the EU | Relevant regulation | |

| Software is considered a product under the Product Liability Directive. | EU Product Liability Directive (B2C). | |

| EU has limited guidance on unfair contractual clauses in B2B contexts.[22] | EU consumer contract law,[23] such as the Unfair Contract Terms Directive. | |

AI as a service

| In the UK | Relevant regulation | |

| Regulation applies especially where software can be updated by a developer after sale (continuing relationship). |

|

|

| Usually governed by contracts / standard terms and conditions. | Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977 (B2B). | |

| In the EU | Relevant regulation | |

| Regulation applies to software-as-a-service. | EU Product Liability Directive (B2C). | |

| EU consumer contract law.[24] |

AI as digital content

| In the UK | Relevant regulation |

| ‘Data which are produced and supplied in digital form’, could cover forms of software / AI. | Consumer Rights Act (B2C). |

| In the EU | Relevant regulation |

| N/A | |

Example scenarios in the UK

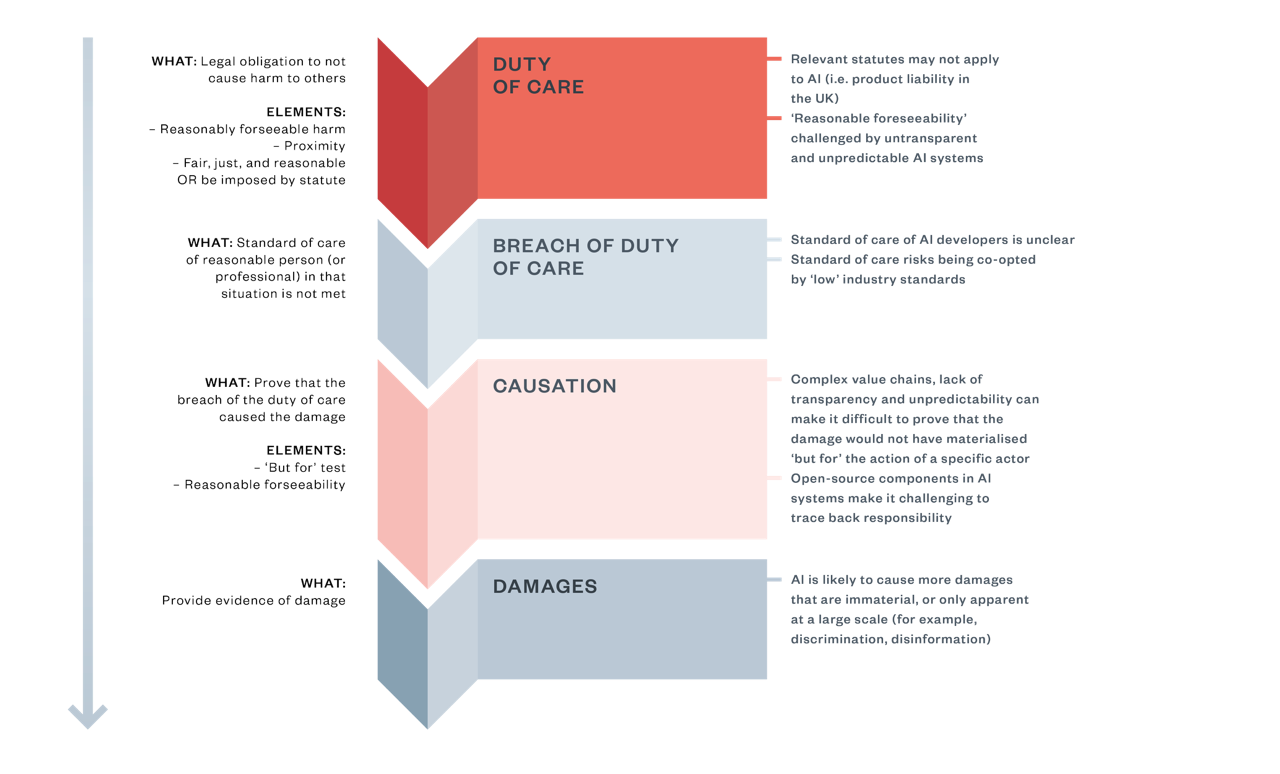

Imposing non-contractual liability onto an actor generally requires multiple elements: a violation of a duty of care (not living up to ‘standard of care’) or some form of strict liability, causation (‘but for’ and reasonable foreseeability) and damage.

AI introduces several challenges that impact on one or more of these elements and make it harder for claimants to effectively sue for compensation through liability. The examples below indicate some of these challenges.

The Appendix provides an in-depth overview of each of these elements.

Example scenario 1: Chatbot gives wrong information

A company hosts an AI chatbot on its website to provide information to customers. The chatbot hallucinates in response to a customer query and provides wrong information about the company’s return policy. The customer consequently sends back an unsatisfactory product after the return window and their refund is refused. The customer sues the company for the chatbot providing wrong information and to get their money back.[25] The company wants to know if they can sue the AI provider for the costs caused by the chatbot’s hallucination.

Considerations:

- It is likely that the AI chatbot was provided by an AI provider under standard terms and conditions. Even for large corporate clients, AI companies tend not to negotiate contractual terms but offer ‘take it or leave it’ provisions. This will likely include a liability exclusion and/or cap to the extent legally possible. If the AI chatbot was provided by a smaller ‘middle’ company (perhaps a customer service system provider), then the contractual terms may not fully push liability onto the user, but challenges remain in proving that the service is not ‘as contracted for’ (see below).

- As the affected party is a company, they cannot rely on consumer protection law (CRA 2015), or on product liability law (CPA 1987) as it does not cover software as a product. The Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977 does apply to B2B contracts and stipulates that a trader cannot limit liability for negligence resulting in death or personal injury, and otherwise may not limit liability unless it ‘satisfies the requirement of reasonableness’.[26] Although the burden of proof to show that the liability limitation is reasonable lies with the AI provider here, courts tend to be reluctant in invalidating clauses. It is therefore unclear if relying on unreasonableness will be successful.

- If the claim can proceed, the company would have to prove that the AI chatbot does not meet the contracted standards for quality. For AI-as-a-service (as AI software does not qualify as a ‘product’ or ‘good’ under UK law) this would amount to proving that the supplier did not act with ‘reasonable care and skill’ or that the service is not ‘as contracted for’.[27] This can be challenging to prove as tech companies are not required to publish materials about the safety precautions they have taken, and it is possible that at the time of a court case it will not yet be fully clear what the standard of care is within the AI industry overall. Moreover, all LLM-based AI systems are known to ‘hallucinate’ from time to time, so it will be challenging to argue that the chatbot was not up to industry standards or falls short of what the company contracted for.

- If it can be shown that the chatbot’s hallucination amounts to a failure of the developer to act with reasonable care and skill, and that the service is not as contracted for, then the company can also sue for the additional damages it has incurred (such as the third-party liability costs from the lawsuit) if the company can show that the breach of contract actually caused damage and that this damage was a reasonably foreseeable result from the breach.

- Similarly, for a claim through negligence, it may be easy to establish that there is a duty of care between the company and the AI developer (there is a paid-for service in place, after all), however the standard of care is a lot more challenging to determine. Therefore, proving that the AI developer breached a duty of care will be difficult. It will also be a challenge to prove that the company’s damages were reasonably foreseeable and could have been prevented by taking reasonable measures, as even AI developers cannot always predict what patterns their AI system will detect and follow. Moreover, if contractual liability caps do apply then this will limit any potential compensation.

This example shows how deployers of AI products may get caught between affected third parties who (reasonably) sue to have their damages compensated and more upstream AI developers who may use contracts or standard terms and services to push liability down the value chain.

It also shows the challenges a company may encounter in trying to prove that an AI system does not meet the contracted-for standard. A chatbot that hallucinates is not necessarily ‘broken’ or performing below reasonable industry care and skill. Moreover, such industry standards are generally unclear.

Companies will likely experience similar challenges in holding upstream AI companies accountable for AI systems performing poorly in other ways, such as an AI system that turns out to be discriminatory or generates outputs that are too similar to copyrighted materials.[28]

This example shows how deployers of AI systems, or actors lower in the value chain, can be burdened with liability risks for harms they themselves could not have reasonably prevented.

Example scenario 2: Automated vehicles

A pedestrian crosses the street at a zebra crossing and gets hit by a self-driving car that fails to slow down and let the pedestrian cross. The car was in full self-driving mode at a high level of automation. The person in the car, the ‘driver’, was not in control of the vehicle and was not signalled by the car to take back control in time. The pedestrian is injured and wants to obtain damages for personal injury.

Considerations:

- The pedestrian does not have a contractual relationship with the ‘driver’ of the automated vehicle (AV) and therefore must rely on non-contractual liability. There are two candidates for who can be held liable: the ‘driver’ and the automated vehicle’s manufacturer. It is established that the car was in self-driving mode at the time of the accident, and the driver had no control over the vehicle. The driver is therefore not at fault for the accident and cannot be held liable. The accident was therefore caused by a fault in the vehicle itself, if we assume there were no other contributing environmental factors at play.

- Automated vehicles have a somewhat special position in the UK: there is dedicated legislation in place to manage liability questions for self-driving car collisions. The Automated and Electric Vehicles Act 2018 establishes that automated vehicles must be insured and that the insurer must pay out compensation to the victims of an accident if it has been established that the automated vehicle caused the accident.[29]

- Provided that the pedestrian has evidence of the damage that resulted from the accident, the insurer must therefore make the initial pay-out to the pedestrian under a form of strict liability. The insurer can then recover the costs from the party that is liable. Essentially, the burden of proving liability is shifted from the pedestrian to the insurer.[30]

- The insurer will in turn try to hold the vehicle developer or manufacturer liable, most likely through negligence or product liability. The insurer has a right to obtain data from the vehicle manufacturer to assist in determining who is liable. The manufacturer likely has a duty of care towards the pedestrian, as they are legally responsible for the safety and functioning of the vehicle while in automated driving mode under the UK’s Automated Vehicles Act 2024.

- As an automated vehicle is a tangible object, product liability might apply, but this is not fully certain in the UK context. For product liability, the insurer would have to prove that the vehicle was defective, i.e. not of the quality that a consumer is entitled to expect. Even with data sharing requirements, it may be challenging to prove where a fault in the vehicle originated from.

- For negligence, the insurer would have to prove that the pedestrian’s personal injury was foreseeable and that the developer should have taken more reasonable precaution – in practice, that their conduct was not in line with the industry standard of care. Even with data sharing requirements, this can be challenging to prove.

- In this scenario, it is relatively easy for the pedestrian to obtain compensation from the insurance company for the damages resulting from personal injury, as the insurer will have to pay them out quickly. However, there are questions around fairness and distribution of risk: if the insurance company cannot recover any of the pedestrian’s damages from the vehicle manufacturer, this does not incentivise the manufacturer(s) to improve the safety of their vehicles.[31]

- The premiums of automated vehicle insurance will be very high if the ‘driver’ cannot decrease the chance of accidents happening through responsible behaviour, and the vehicle manufacturer is not held liable and therefore similarly not incentivised to practice responsible behaviour.

This example shows the interplay between strict liability, insurance and risk allocation, and how insurance can help ensure that affected people are compensated quickly.

However, the example also shows how an insurance scheme does not automatically incentivise the right actors to take precautions to prevent harms from materialising, if the insurer cannot recover costs from the liable party (the vehicle manufacturer).

Moreover, automated vehicles are subject to a dedicated regime that helps affected parties obtain swift compensation and shields ‘drivers’ when they are actually not in charge of the vehicle.

Not all automated devices are subject to insurance, such as automated lawnmowers.[32]

- If an automated lawnmower caused damage, then the affected person would have to rely on fault liability (negligence) to obtain compensation. They would have to prove that the owner of the lawnmower did not act with sufficient care, for example if they deployed it outside of recommended uses. But if this is not the case, the affected person may struggle to show that there was a breach of a duty of care which caused the damage. Especially as, unlike in the automated vehicle example above, there is no duty imposed on the lawnmower’s manufacturer to share data with the claimant.

- Moreover, if the owner was held liable for the damage caused by the automated lawnmower while not being able to effectively control how the lawnmower operated, this may raise questions of fairness.

- If they (as a third party) would try to sue the manufacturer of the lawnmower, they might similarly struggle to evidence that the manufacturer did not exercise sufficient care (negligence) or to prove that the lawnmower was defective (product liability).

- If the affected person was the owner of the lawnmower, they might be able to bring a claim against the manufacturer through product liability. But they would first have to prove that the automated lawnmower was defective, which requires technical documentation and expertise.[33]

This shows the difficulties of establishing a breach of a duty of care and proving causation or defectiveness in the case of (integrated) AI products. It also highlights the relevance of having clear legal rules for who is liable in the case of an autonomously operating AI system.

In the automated vehicle scenario, the ‘driver’ is shielded from liability by dedicated legislation for accidents that are out of their control. In the automated lawnmower scenario, the question of who is liable is not as clearly defined. It may seem unfair to hold the owner liable if they could not control how the lawnmower operated, but there are (again) challenges in proving that the AI developer had a duty of care towards the affected person, and that their failure to take reasonable care caused the lawnmower to cause damage. There is also no dedicated regime in place for information sharing that would help the affected person obtain data on how and why the lawnmower malfunctioned.

Example scenario 3: Hiring and discrimination

A jobseeker is applying for jobs. Most of the companies they apply for use AI hiring systems to sift through the CVs of applicants and rank the most promising candidates. The jobseeker keeps being rejected by the AI hiring systems, even though they are overqualified for most of the jobs they apply for. They decide to experiment with a few versions of the CV. When they change the font and background colour and upload the CV to the system, they start to be invited to interviews.

The jobseeker is frustrated. It appears that they have applied for dozens of jobs but were filtered out by the AI system due to the design of their CV. This has potentially lost them the opportunity to interview for jobs they were well-qualified for and possibly months of lost income.

‘CV layout’ is (mostly) irrelevant to the quality of their application and it is not a protected characteristic under discrimination laws. The jobseeker wonders if they can sue the companies that were hiring or the AI developer that developed the system for lost opportunity and potential lost income.

Considerations:

- There is no contract or standard terms of service in place between the jobseeker and the hiring companies or the AI developer. The jobseeker cannot rely on the Consumer Rights Act 2015 and other legislation on consumer contracts.

- Although affected third parties can make claims against the trader under the UK Consumer Protection Act 1987, an AI system like this is not considered a ‘product’ in the UK so the UK CPA 1987 does not apply. The CPA 1987 also only covers personal injury and damage to property, so would be inapplicable to the damages that the jobseeker is seeking to recover.

- The only route open is negligence, which requires the jobseeker to prove a duty of care, breach of duty, causation, reasonable foreseeability and damages. In this scenario, all of those are difficult to prove:

- The jobseeker would have to prove that the AI developer had a duty of care towards them. The developer did not deal with the jobseeker directly, the case concerns ‘pure economic loss’, and the AI developer likely has not assumed responsibility for this kind of damage. It is unlikely that the duty of care would be established. However, there may be a duty of care between the hiring company and the jobseeker.

- Although it may be argued that an AI hiring system should not filter out candidates based on arbitrary non-content related aspects such as CV layout or font, it is not clearly established practice that this would breach a duty of care on behalf of the prospective employer.

- The jobseeker cannot definitively prove that their application was rejected because of the CV design, and that this was caused by either the instructions given by the hiring company or by the AI developer’s actions. It is thus also challenging to satisfy the ‘but for’ test.

- It is not clear if it was reasonably foreseeable at the time that the AI developer put the system on the market, or when the hiring company deployed it, that it would filter applicants based on CV design and that this would harm applicants.

- The jobseeker’s damages constitute loss of opportunity and pure economic loss, which is complex to establish a duty of care for. Estimating the damages might also be complex, as it is not clear that the jobseeker would have been hired for the job. Even if product liability in the UK covered software, it does not cover ‘pure economic loss’ damages such as this.

This example shows how the probabilistic nature of many AI systems can create new types of unforeseen vulnerabilities and harms that do not easily fit into existing regulations. It also shows challenges in establishing a breach of the duty of care and for proving causation. Even with technical expertise and access to sufficient evidence, the jobseeker would struggle to definitively prove that their rejection was caused by the CV design and that such harm was reasonably foreseeable.

Establishing a duty of care between the AI deployer (the hiring company) and the jobseeker will be slightly easier (although still challenging) than between the jobseeker and the AI developer.

This may challenge notions of fairness in liability distribution along the value chain as it is the AI developer that has most insight into the AI system and would be better placed to foresee potential harms and tackle them at scale.

Even if a duty of care can be established, it is very unclear what the standard of care would be in this situation for both the hiring company and the AI developer. Additionally, this example illustrates the challenge of finding a route to compensation for immaterial damages such as financial loss or loss of opportunity.

Summary of challenges

The main challenges for liability for AI systems, possible solutions and, where identified, the potential limitations of those solutions are summarised below.

Figure 2: Liability in the AI value chain

Challenge: Not clear what ‘duty of care’ entails for different actors involved in developing and operating AI systems

Legal problem

Establishing a breach of the duty of care: having to establish what the standard of care is for that actor.

Possible solutions

- Incentivise AI safety research, invest into the development of AI standardisation and promotion of responsible industry practice.

- Strict liability for some very high risk, dangerous or prohibited AI uses.

- Professionalisation of AI development professions

Limitations

Industry standards can set too low of a bar, development may be too slow and uncertain for high and immediate risks.

Challenge: Agentic and autonomous capabilities & capacity for human control

Legal problem

Duty of care: having to establish what the standard of care is for actors developing or operating AI systems with higher levels of autonomy.

Possible solutions

- Strict liability for systems with high level of autonomy.

- Consider how humans may interact with AI agents to determine when a user ceases to be legally responsible.

- Vicarious liability and legal personhood.

- Agent IDs and visibility measures.

Limitations

Strict liability is sometimes argued to ‘deter innovation’, but can also be seen as redirecting innovation towards less risky applications.

Challenge: Complex value chains & opacity

Legal problem

Causation: difficulty proving the harm would not have happened but for the action/omission of a certain actor.

Possible solutions

- Joint and several liability.

- Transparency enhancing measures.

- Duty to disclose evidence.

- Reversal burden of proof in cases of high technical complexity.

Limitations

Reversing evidentiary burdens may increase the burden on companies – this is problematic if they do not have access to technical documentation across the whole value chain.

Challenge: Open-source AI

Legal problem

Causation: does open-source software ‘sever’ the liability of upstream developers?

Possible solutions

- Liability located with downstream actor that derives economic benefit.

- Role of hosting platforms.

Challenge: Unpredictability of AI systems (particularly LLM-based)

Legal problem

Causation: difficulty establishing that a harm is reasonably foreseeable.

Possible solutions

- Tracking of AI harms.

- Promoting human-computer interaction research.

- Strict liability for unpredictable high-risk systems.

Challenge: Harms are ‘hard to measure’ and substantiate, immaterial and systemic

Legal problem

Damages: many liability systems only cover material harms.

Possible solutions

- Allow for (capped) immaterial damages in AI cases.

- Collective action lawsuits.

Challenge: Contracts or standard terms of service distribute liability away from upstream actors

Legal problem

Provisions may preclude users or downstream actors from bringing a liability claim against a more upstream company.

Possible solutions

Expand work on illegal unfair contractual clauses for AI to support.

Limitations

Current prohibitions on unfair contractual clauses relating to liability focus on death or personal injury.

The seven challenges and the potential ways of addressing them stated in the table above will be discussed in more detail in the subsequent sections of this report.

Establishing a breach of the duty of care: the standard of care

Takeaways

- Negligence uses a flexible standard of care that can evolve along with our knowledge and understanding of technology and safety practices. The standard of care is higher for specialised professionals.

- The standard of care will be crystallised over time and will draw on industry practice, legal standards and scientific knowledge.

- If industry practice around safety lags, this may impact the standard of care that AI developers are held to. Consequently, the standard of care can be ‘too low’, which would induce suboptimal precaution and increase the risks of AI products above societally desirable levels.

- The promotion of AI safety science in academia and industry, and the development of independent standards can help prevent a suboptimal standard of care.

- In instances of AI systems that carry a very high risk, it may be warranted to impose strict liability, potentially coupled with mandatory insurance.

- Professionalisation of AI developers can help improve the understanding of ethics of those working in AI labs, and create personal incentives for AI developers to practice safety. Fiduciary duties can also be imposed on whole institutions.

A standard of care is the reasonable level of precaution that an actor is required to take.[34] For AI, the standard of care may influence when AI developers can be held liable for failing to practice sufficient safety precautions if their product consequently causes harms.

This is mostly relevant for liability through the tort of negligence (i.e. the actor not acting in line with the standard of care will breach their duty of care if damage occurs as a result).

The standard of care is less relevant for forms of strict liability, as that generally does not require the defendant to be at fault; they are held liable regardless of whether they exercised sufficient care or not.

For new goods or activities, a standard of care will generally emerge over time. For example, someone driving a car must perform the task with the care and skill of an ‘ordinary driver’.[35] Since the introduction of the car, legislation and case law has developed to set out what ‘the care and skill of an ordinary driver’ means. Over time, standards have been established such as adhering to traffic rules, paying attention to the road and making sure everyone in the vehicle wears a seat belt. At the same time, a safety regime has emerged that clarifies what the standard of care is for car manufacturers, such as performing certain safety tests.

Challenges for AI liability

AI is a fast-developing technology and the advancing technology makes it challenging for the legal system to keep up and provide clarity on the standard of care that a developers or user should be held to when an AI system causes harm, even if the product is already on the market.[36]

As a result, it may be unclear for affected persons and courts what standard of care a developer or user of an AI product should be held to when an AI system causes harm. Indirectly, this lack of clarity also creates a liability risk for developers, users and potentially insurers, as they do not know what level of precaution they should exercise to be able to defend themselves from liability risk. In short, there are no clearly established and recognised ‘best practices’ around AI development or deployment.

A standard of care may be established through the development of industry practice, regulation and scientific research. In the context of AI this means that the following kinds of instruments will likely be weighed by courts in liability cases to establish what the standard of care is for the AI developer:

- Industry standards: For example, those developed by standards bodies such as CEN/CENELEC,[37] the NIST AI Risk Management Framework[38] or voluntary commitments[39] to AI Safety, like the Frontier AI Safety Commitments.[40] Assurance mechanisms and certification regimes may help track and enforce such standards.[41]

- Legal standards: Like the EU AI Act and accompanying Code of Practice,[42] the UK’s regulatory principles,[43] or Colorado’s Consumer Protection for AI Act.[44]

- Scientific research: The reasonable care that an AI developer or deployer is supposed to take will develop alongside scientific advances. If better techniques for evaluating AI models and systems are developed (that are not significantly more expensive), it is to be expected that such techniques will be adopted by the industry. For example, if an AI model fails basic well-established red-teaming exercises that other AI models can pass, that may indicate that its developers did not exercise sufficient care in evaluating the model and developing its safeguards.

This system of reasonable care has its advantages and disadvantages. On the one hand it is flexible, as the threshold for reasonable care will move along with scientific breakthroughs and advances. For example, the UK’s Consumer Protection Act (CPA) 1987 states that a producer is only liable for a defective product if ‘the state of scientific and technical knowledge at the relevant time was not such that [the producer] might be expected to have discovered the defect’.

In other words, complying with the ‘state-of-the-art’ of scientific knowledge and practice can be a defence for producers to protect them from liability. In this sense, the standard of reasonable care is more flexible than a legislative standard.

On the other hand, if an entire industry lags in implementing safety practices, there is a risk that the bar for reasonable care will be set too low. In general, sometimes a majority of actors acting in a certain market may be ‘engaging in common patterns of unreasonably dangerous conduct, and courts must correct such errors’.[45]

Also, in areas that are still emerging, contested or where reaching consensus is challenging, it may be difficult to establish that there is a ‘standard industry practice’ that can inform the reasonable care that an actor should take.[46]

Additionally, judges determining what the standard of care is in a specific case will consider industry standards in absence of applicable statutes and case law – but are not bound by it.[47]

Moreover, AI companies are not always incentivised to be transparent about the risks that they know their products create, as this would require them to also take measures to address those risks if this is technically and economically feasible. The section on ‘Complex value chains and opacity’ addresses transparency issues in more detail.

Potential solutions

AI safety research, standards and assurance

As stated above, it will take time to develop a standard of care for AI through case law and jurisprudence. Additionally, there is a risk of the standard of care being set ‘too low’ if industry standards on safety practices lag behind AI development.

Still, promoting the development of safety practices through standards and scientific research, for example through AI safety institutes and grant funding for AI safety work, may contribute to the development of AI safety standards and the crystallisation of a standard of care.

Industry actors are best placed to understand how their products work in a technical sense. They also have access to user data that will tell them how consumers are using their products. This means that industry actors themselves will always be best positioned to understand how their products might cause harm and what can be done to prevent those harms, and to anticipate new emerging risks.

For risks that are clear and well-defined, independent assurance bodies may play a role in setting best practices on the due diligence and evaluations required for addressing such risks.

Additionally, legal rules can also help clarify what safety precautions can be expected from tech companies. In essence, product safety legislation sets a legal standard for the behaviours and precautions to be expected from product developers.

As industry, academia and standards bodies can together help advance AI safety science and create standards based on that, each of them should be incentivised and enabled to do so. As the standard of care is flexible and will adjust to developments in science and ethics, contributions from various sources that support the development of ‘best practices’ in AI safety can contribute to crystallising the standard of care over time.

Strict liability

In contexts where it has been established that the use of a certain AI system carries unreasonably high risks, it may be warranted to impose strict liability on developers and/or users who choose to develop and deploy such systems. An example of this could be the development and use of an AI agent with a high level of autonomy and limited ability for human oversight (see the section on ‘Agentic and autonomous capabilities’). Strict liability is often used to govern ‘dangerous activities’ that will always carry an element of risk even when appropriate care is taken, especially where actors derive economic benefit from creating a risk.[48]

Strict liability negates the need to establish the standard of care (and prove breach of duty) and is therefore less burdensome on the affected person and the courts. In an economic sense, strict liability makes sense in situations where negligence claims are difficult or in practice do not hold liable the person best placed to prevent the harm, resulting in difficulties in obtaining redress as well as suboptimal levels of deterrence and precaution.

Strict liability in such situations, if imposed on the ‘cheapest cost avoider’, can be effective in pushing the strictly liable actor to take higher levels of precaution as they know they will be held liable for any damage they create.[49]

However, it may lead to moral hazard if the ‘victim’ could have also played a role in preventing the damage.[50] Some authors consider that strict liability may cause actors to become overly careful and may lead to an economically suboptimal level of a certain activity. Mandatory insurance could provide a solution here (see the case study on cars and nuclear power plants in the section on ‘Insurance’ in the Appendix).[51]

Professionalisation of AI developers and fiduciary duties

The profession of AI developer is specialised and requires a high level of technical expertise. Research has shown that AI developers are often aware of ethical concerns related to their work, but either do not have enough knowledge or organisational support to act upon it.[52]

Other highly specialised professions that encounter ethical dilemmas in their work, such as legal and medical professionals, are subject to fiduciary duties towards their patients, and ethical considerations. For clinicians, this is best known as the Hippocratic oath, ‘do no harm’.[53] These regulated professionals must complete ethics courses to be awarded their title and can be stripped of it or fined if found to act in contradiction with their duty of care.

Some authors have suggested that the profession of ‘AI developer’ or ‘AI engineer’ could also become subject to professionalisation and oversight by a regulatory body, like regular ‘engineers’ already are in the UK (see the section on ‘Fault liability’ in the Appendix).[54] This would help raise awareness about responsible development and ethics among the AI workforce, and could create personal incentives for AI developers to create a culture of social responsibility in AI companies.[55] It would formalise a professional standard of care that individual AI developers can be held to.

There are some drawbacks to this approach. Some research shows that even in regulated professions, fiduciary duties are followed more by the letter than in spirit, essentially making their professional duty of care into a compliance checklist.[56] Additionally, professionalisation increases the barrier to entry of a profession, potentially creating professional protectionism.[57] There is also a more fundamental difference between AI developers and lawyers or doctors. The latter two have a clear object (their client or patient) in whose best interest they are required to act. For AI developers, it is unclear who the fiduciary duty is towards.[58]

In some industries, the fiduciary duty is imposed on a whole service provider rather than on an individual professional, such as in the financial services industry. Financial service providers must adhere to the ‘consumer duty’, which means that they need to deliver good outcomes for consumers, requiring the providers to act in good faith towards their customers and avoid causing foreseeable harm to them.[59]

A breach of the consumer duty can provide a basis for a liability claim through the court system but may also be taken to the Financial Ombudsman, who can provide dispute resolution for affected customers and support them in obtaining compensation.[60] Senior managers within financial services can be held personally liable for, among others, violations of the consumer duty (see the section on ‘Vicarious liability’ in the Appendix for further explanation).[61]

Agentic and autonomous capabilities: autonomous systems and their ‘controller’

Takeaways

- Increasingly autonomous and agentic features in AI systems create challenges for the attribution of liability by shifting the ability to control the actions of the AI agent away from the user.

- It may be appropriate to impose strict liability for AI agents that operate at a very high level of autonomy, where the agent is able to pursue open-ended goals in complex environments, and where human oversight is limited if not non-existent. Such strict liability should primarily be imposed on the AI developer, analogous to the UK Automated Vehicles Act, but should not completely shield the AI agent user from liability risks as this might create moral hazard. Liability should be shifted away from users for outcomes they cannot control, but still hold users liable when the choice to use a certain AI agent for a certain task is careless.

- Using strict liability for very autonomous AI agents may also be helpful to steer towards AI agents that are subject to human oversight (that would not be subject to strict liability) and away from ‘uncontrollable’ agents.

- Vicarious liability and legal personhood are debated topics in research circles, but both come with significant and potentially unsurmountable hurdles.

- Introducing frameworks that increase visibility of AI agents, such as agent IDs and agent activity logs, will be necessary to help track agent activity and allocate liability.

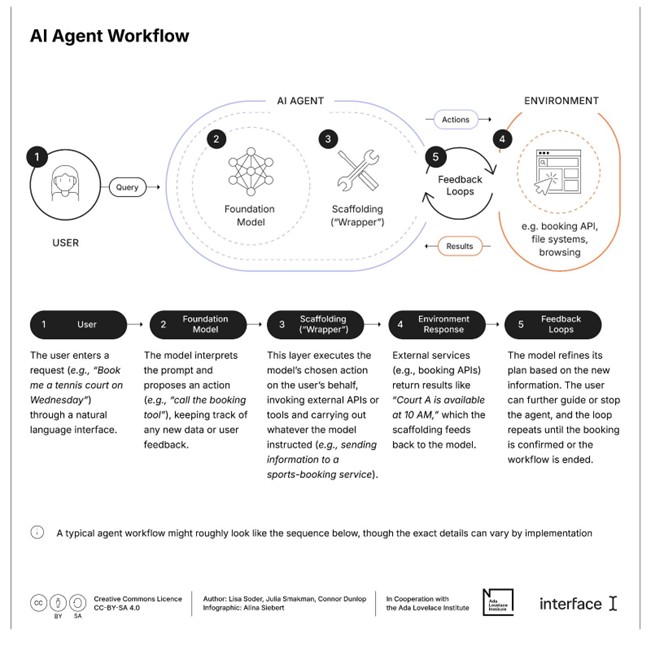

After the introduction of large language models (LLMs), AI companies have started developing ‘agentic AI systems’, to the extent that some have called 2025 the ‘year of AI agents’.[62]

Agentic AI systems, sometimes referred to as ‘AI agents’, are AI systems that are able to take actions: they can ‘autonomously plan and execute complex tasks in digital environments with only limited human oversight’.[63] The terms ‘AI agent’ and ‘agentic AI system’ are used interchangeably here.

Examples include an ‘AI agent’ that works as a personal assistant (like OpenAI’s Operator) but may also include an AI system that automates workflows without necessarily ‘conversing’ with a human.

Earlier versions of agentic AI systems may include rule-based systems that execute functions in an ‘if-then’ function. For example: ‘If the temperature drops below 18°C, then [the agent] turns on the heating.’ Newer versions of agentic AI systems tend to be LLM-based, which can make them more adaptable, but also more unpredictable.

Figure 3: Example workflow of an agentic AI system

Challenges for AI liability

Earlier research has highlighted that agentic AI systems raise new challenges around ‘safety, alignment and misuse’.[64] The more autonomous systems become, the greater their potential for facilitating harmful misuse or accidents. Additionally, if agentic AI systems become more widespread, they might interact with each other in multi-agent systems, amplifying risks.[65]

Most of the challenges introduced by agentic AI systems for liability apply to the questions raised by AI systems in general, but the (increasing) autonomy of agentic AI systems may intensify them:

- Damages: Agentic AI systems may cause damages that are immaterial or systemic (see the section on ‘Types of harms’).

- Allocation of responsibility: It may also be challenging to trace back responsibility for harms resulting from the use of agentic AI systems to the responsible actors, due to their complex value chains (see the section on ‘Complex value chains and opacity’) and potential delegation of responsibilities to other AI agents. Additionally, for agentic systems with high levels of autonomy, there is a lack of visibility – it may not always be clear ‘when, where, how, and by whom certain agents are being used’.[66]

- Harm prevention: Agentic AI systems may also further complicate the foreseeability of harms, as their ability to autonomously interact with online environments increases their unpredictability (see the section on ‘Unpredictability and reasonable foreseeability’).

The technical features built into AI agents may also promote or hinder a user’s ability to effectively provide oversight of the AI agent and its actions. Additionally, AI agents may not always be perfectly aligned with their user’s intentions.

This section will focus on the problem of invisibility and some of the challenges around allocation of responsibility, notably the nuancing of human control over autonomous systems and technical features that hinder or enable oversight. Other challenges will be covered in other sections of this paper on ‘Types of harms’, ‘Complex value chains and opacity’ and ‘Unpredictability and reasonable foreseeability’.

Invisibility

To properly identify where AI agents have been used and potentially have caused harm, it is critical to have visibility into AI agents.[67] Whereas through the GDPR people have a right to know when they are subject to automated decision-making if it has a legal effect or otherwise similarly significantly affects them, it may not always be clear to third parties when they are dealing with an AI agent on the internet or with a real person. As AI agents can now solve CAPTCHAs,[68] it may become increasingly difficult to track AI agents online, distinguish whether a harm was caused by a human or an AI agent, and identify who was behind the AI agent that caused the harm.

Nuancing control

Increasingly autonomous agentic AI systems raise questions about the interplay of control and responsibility between the system and its user. Other AI systems are only capable of advising on actions or can act with a very limited range of pre-programmed actions. The paradigm shift towards more autonomous agentic AI systems means we are moving from AI systems that tell you how to fill in a form to ones that do it for you, and from agentic workflows that can control the temperature of your house to an agentic AI system that can manage your household tasks and professional appointments.

If an AI system can make a plan and execute it autonomously, then the user has less control over the eventual outcome. The user may struggle to foresee how the AI agent will act (due to increased unpredictability) and also have less opportunity to take precautionary measures, depending on the opportunities for human oversight that are built into the AI agent.