Great (public) expectations

New polling shows the public expect AI to be governed with far more rigour than current policy delivers

4 December 2025

Reading time: 23 minutes

Key insights

In the King’s Speech in July 2024, the UK government promised to introduce statutory legislation on frontier AI models. However, as 2025 draws to a close, the anticipated consultation on an AI Bill has yet to appear, leaving the UK without clear rules for managing some of today’s most powerful technologies.

As momentum behind meaningful legislation appears to stall, this briefing presents new research showing that this delay – and the government’s broader shift away from regulation – is increasingly out of step with public attitudes. The research examines not only whether people support regulation, but also how they expect it to function, and where gaps between public expectations and policy ambition may lie.

The findings show a clear misalignment between public expectations and government ambitions for AI – an imbalance that risks eroding trust and undermining support for future governance efforts. The government is making a significant bet on AI’s potential but, without clear commitments to safe and responsible use, it risks losing public confidence. When people do not trust that government policy will protect them, they are less likely to adopt new technologies, more likely to lose confidence in public institutions and services, and ultimately less inclined to support the government itself.

Key findings

- The public prioritise fairness, positive social impacts and safety. AI is firmly embedded in public consciousness and 91% of the public feel it is important that AI systems are developed and used in ways that treat people fairly. They want this to be prioritised over economic gains, speed of innovation and international competition when presented with trade-offs.

- The public feel disenfranchised and excluded from AI decision-making, and mistrust key institutions. Many people feel excluded from government decision-making. 84% fear that, when regulating AI, the government will prioritise its partnerships with large technology companies over the public interest.

- The public support independent regulation. The UK public do not trust private companies to self-regulate. There is strong public support (89%) for an independent regulator for AI, equipped with enforcement powers.

- The public expect ongoing monitoring and clear lines of accountability. People support mechanisms such as independent standards, transparency reporting and top-down accountability to ensure effective monitoring of AI systems, both before and after they are deployed.

Introduction

Since coming into power, the UK government has demonstrated strong political will to invest in AI, scale its deployment and embed it across society – including through the UK-US tech prosperity deal promising £31 billion to develop UK AI infrastructure. However, the government has given few indications of its intentions to match this focus on innovation and adoption with the development of robust safeguards.

The anticipated consultation on an AI Bill, designed to introduce essential safeguards for frontier AI, is unlikely to occur before next year, delaying the implementation of formal regulatory oversight for these technologies. Instead, the government is encouraging an enabling, rather than enforcement, approach to AI adoption, with the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT) prioritising AI sandboxes (controlled environments where businesses can test innovative products, often with regulatory exemptions) while legislative options remain undecided.

The rapid pace of AI development means that delays to implementing safeguards carry significant risks. The current lack of oversight departs from established norms: regulatory mechanisms that are standard in other high-impact domains remain largely absent in AI governance, as illustrated in the table below:

This regulatory gap is also out of step with public expectations. In a nationally representative survey conducted by the Ada Lovelace Institute and the Alan Turing Institute in March 2025 (fieldwork undertaken October–November 2024), 72% of the UK public said that laws and regulation would increase their comfort with AI – an increase of ten percentage points from 2022/23. This demand for accountability reveals a growing gap between public attitudes and expectations and the UK government’s current regulatory approach.

Building on this analysis, we conducted rapid-response polling with a nationally representative sample of 1,928 participants, to gain more granular insights into public attitudes towards AI regulation.[1] This briefing presents our findings, which explore not only whether people support regulation, but how they expect it to work and where gaps exist between public expectation and policy ambition.

The public are a critical stakeholder in the UK’s AI ambitions and research shows they hold informed, considered views on these technologies. For AI to positively transform society, its development, deployment and governance must reflect public attitudes. Without this alignment, the government risks investing in technologies that deepen inequalities, erode trust and ultimately fail to serve the public interest.

97% of people say they have heard or read a little or fair amount about AI.

Finding 1: The public prioritise fairness, positive social impacts and safety

Public awareness of AI is widespread, and the use of AI tools is increasingly common in everyday life. The public hold considered views on how AI should be governed and what principles should guide its development.

Almost everyone surveyed reported at least some awareness: 97% of people say they have heard or read a little or fair amount about AI. This confirms that AI is a mainstream issue shaping public discourse and daily experience.

As awareness and use of AI becomes widespread, the public is forming considered views on how it should be deployed and governed.

Exploring values alignment and trade-offs

Narratives around AI regulation are often framed around principles – like fairness and transparency – and trade-offs. For example, regulation is said to support safety but stifle innovation and slow progress. To test how these narratives resonate with the public, we asked people to what extent they agreed or disagreed with a series of statements about AI development, use and governance.

Safety should come before speed

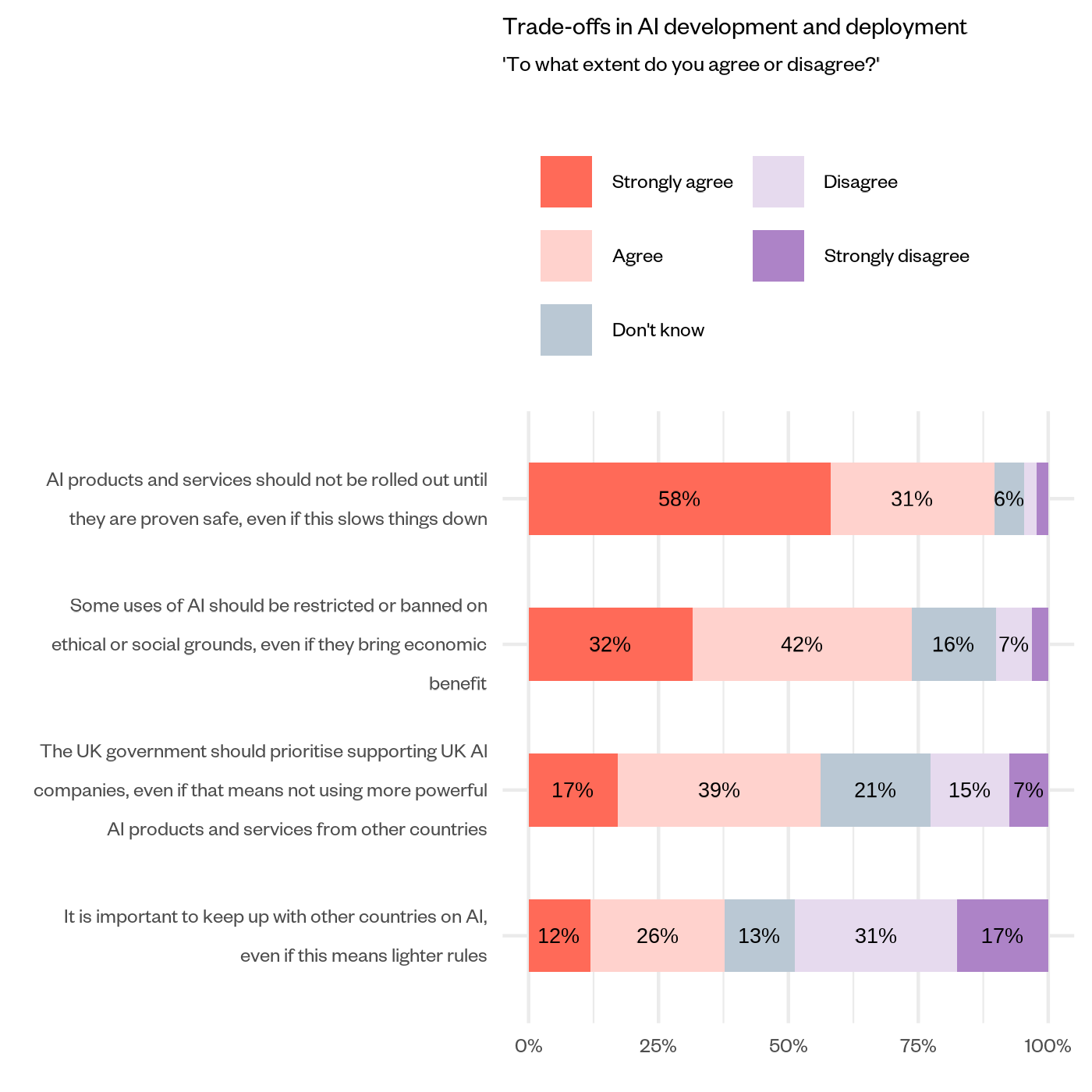

When asked about the pace of AI development, 89% agree that: ‘AI products and services should not be rolled out until they are proven safe, even if this slows things down.’ This reflects a strong preference for a cautious, evidence-based approach to deployment, suggesting the public are willing to trade speed for safety and reliability.

Figure 1: Trade-offs in AI development and deployment

Due to rounding percentages may not total 100%

Setting limits on acceptable use

Economic benefits alone are not enough to justify all uses of AI. Three-quarters of the UK public (74%) agree that some applications should be restricted or banned on ethical or social grounds, even if they bring financial or competitive advantages. This demonstrates a clear appetite for enforceable ‘red lines’ rather than a ‘growth at any cost’ approach.

Fairness is essential

Fairness remains a central public concern. Nine in ten people (91%) feel it is important that AI systems are developed and used in ways that treat people fairly. This sentiment is consistently held across age groups, education levels and among those that both use and do not use AI tools. This demonstrates that the public place a high priority on fairness in AI, signalling this should guide decisions about design, deployment and governance.

91% of the public think it is important that AI systems are developed and used in ways that treat people fairly

Preference for UK AI sovereignty

Views on AI sovereignty reveal that many people want the UK to maintain control over the tools it adopts and the companies it supports. A majority (56%) agree that: ‘The UK government should prioritise supporting UK companies, even if that means not using more powerful AI products and services from other countries.’ This indicates a preference for national investment and strategic independence in AI development but may also suggest a recognition that the government can exert greater control and oversight over domestic firms than international providers.

Rejecting a ‘race to the bottom’

The public prioritises safety and accountability over international competition. We found that 48% disagree that: ‘It is important to keep up with other countries on AI, even if this means lighter rules.’ An additional 14% say they are not sure while 38% agree with this statement. This indicates that nearly half of the UK public reject the idea of a regulatory ‘race to the bottom’, where the UK would compromise safety and accountability in pursuit of international competitiveness.

Together, these findings reveal a clear misalignment between the government’s emphasis on innovation and competitiveness at the expense of governance, and public expectations that centre on fairness, safety and accountability. Aligning policy and governance with these values will be essential to building trust, ensuring adoption and delivering AI that genuinely serves the public interest.

Finding 2: The public feel excluded from AI decision-making and mistrust key institutions

A strong sense of political disenfranchisement, coupled with low trust in both government and private companies, underpins how people perceive AI governance and whose interests it serves.

Feeling excluded from decision-making

Many people hold clear opinions on what AI governance should look like yet feel they lack the ability to shape its development or influence government decisions. Two-thirds of the UK public (60%) do not feel that people like them have a say in what the government does. This feeling of disempowerment is higher:

- among older members of the public than younger; 70% of 55-74-year-olds feel this way compared to 47% of 18-34-year-olds.

- for those that are less digitally confident; 75% feel this way compared to 58% of those who are digitally confident.

- for those with lower levels of overall education; 70% of those with no formal qualifications feel this way compared to 52% of those with a degree.

These statistics suggest that the groups that perceive themselves as most likely to be negatively affected by AI, such as those without higher education qualifications, lower digital confidence or older people are also those who feel least able to shape how it is governed. This compounds existing structural inequalities, where those with the least power in society (who are most likely to have experienced inequalities and under-delivery on promises of support and services) are also least heard in conversations about technological change.

Figure 2: Political empowerment

Due to rounding percentages may not total 100%

Concerns over government-industry partnerships

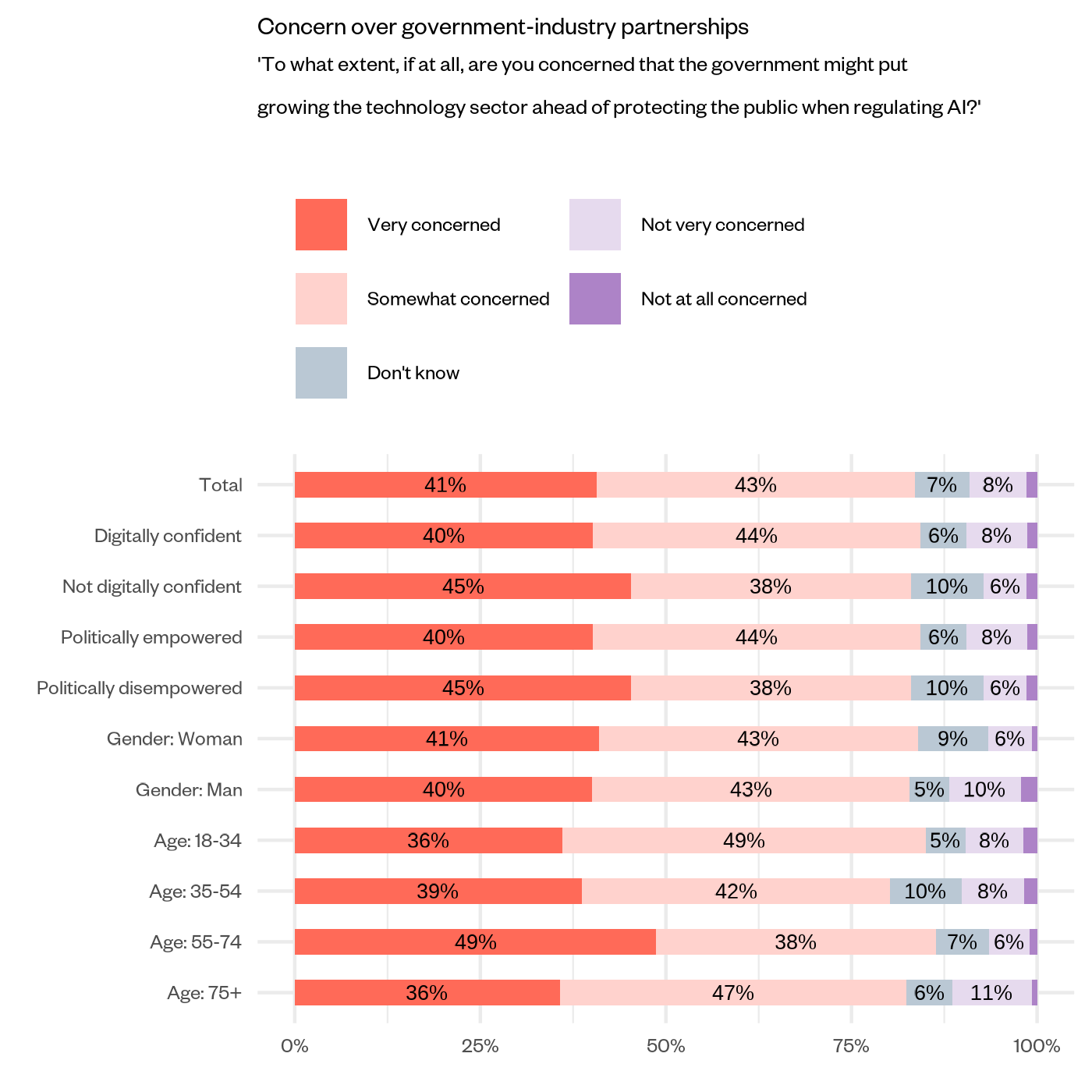

This sense of exclusion is reinforced by widespread concern that the government will prioritise its relationships with large technology companies over the public interest. 84% of people are concerned about the government putting the needs of the technology sector ahead of the public when regulating AI. These concerns are consistent across age, digital confidence, gender and feelings of political empowerment. They also echo findings from our previous research about the role that large technology companies play in the public sector more broadly.

Figure 3: Government-industry partnerships

Due to rounding percentages may not total 100%

Low trust in technology companies and in government

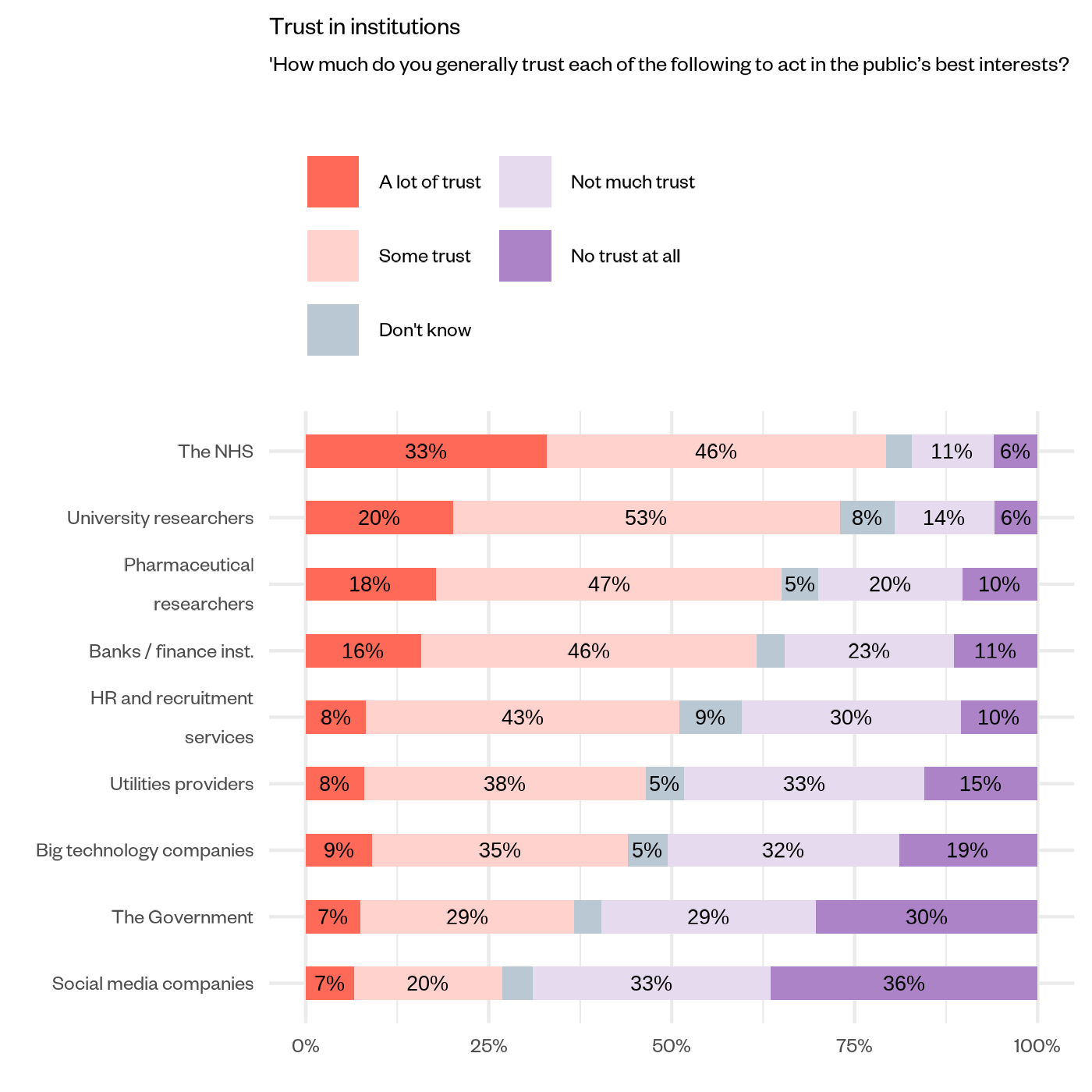

Public trust in institutions shaping AI remains low across the board, with both private companies and government struggling to earn confidence. Over half of the UK public (51%) say they do not trust large technology companies, including social media companies, to act in the public’s interest. Distrust is particularly high for social media companies specifically, at 69%.

At the same time, trust in government is also weak: 59% of people say they do not trust the government to act in the public’s interest.

These figures highlight a broader issue: the public see both industry and government as falling short in safeguarding societal interests. This widespread distrust underscores the importance of independent oversight and governance mechanisms, shaped by public attitudes and meaningful public involvement. These mechanisms can ensure AI is developed and deployed in ways that genuinely reflect the public interest, rather than relying solely on government or private companies to self-regulate.

Figure 4: Trust in institutions to act in the public’s best interests

Due to rounding percentages may not total 100%

These findings highlight a deep disconnection between the public and the institutions shaping the UK’s AI future. Feelings of exclusion and mistrust, particularly among those already marginalised, suggest that the government’s current approach to AI regulation risks reinforcing existing inequalities and further eroding public trust. If trust continues to decline, the government may face significant barriers to public support, adoption and the successful implementation of AI policies designed to benefit society.

Finding 3: The public support independent regulation

A strong public demand for accountability and safety drives expectations around how AI should be governed. People are clear that meaningful oversight requires both independence and the authority to intervene decisively when risks arise. Independent regulation of AI is a clear public priority, reflecting widespread desire for impartial oversight. Nearly nine in ten people (89%) say it is important that AI is regulated independently, while only a small minority (1%) feel independent regulation is ‘not at all’ important.

89% of people say it is important that AI is regulated independently.

Regulators should have robust enforcement powers

The public expect regulation to have ‘teeth’, in the sense that it will have the power and authority to hold technology companies to account and enforce rules effectively. Specifically, 89% of people believe government and regulators should have the authority to halt the use or sale of any AI system found to cause harm. Among these:

- 85% support powers to take restrictive actions such as temporarily or permanently removing harmful tools from public access.

- 64% would back technical interventions to mitigate risks, such as requiring amendments to training data or system settings.

These results demonstrate a clear public expectation that AI should be regulated as rigorously as other high-risk sectors, such as finance, aviation and pharmaceuticals, where authorities have strong powers to intervene and prevent harm. Without similarly robust enforcement mechanisms, AI regulation risks falling short of public expectations, undermining trust and allowing potentially harmful systems to persist.

89% think the government or regulators should have the power to stop the use or sale of an AI system in the UK if it were found to cause harm.

Finding 4: The public expect ongoing monitoring and clear lines of accountability

There is strong public demand for monitoring and accountability mechanisms to ensure that AI systems are safe, transparent and responsibly governed.

Support for mandatory safety testing

The UK public show strong and clear support for the safety testing of AI systems, both before and after they enter the market. A significant majority of people (86%) believe AI models should be proven safe prior to their release, while a substantial group (70%) support post-market safety checks. Two-thirds of people (66%) endorse both pre- and post-market testing. The higher support for pre-market testing reflects the public’s views that AI tools should be deemed safe before they interact with people or society.

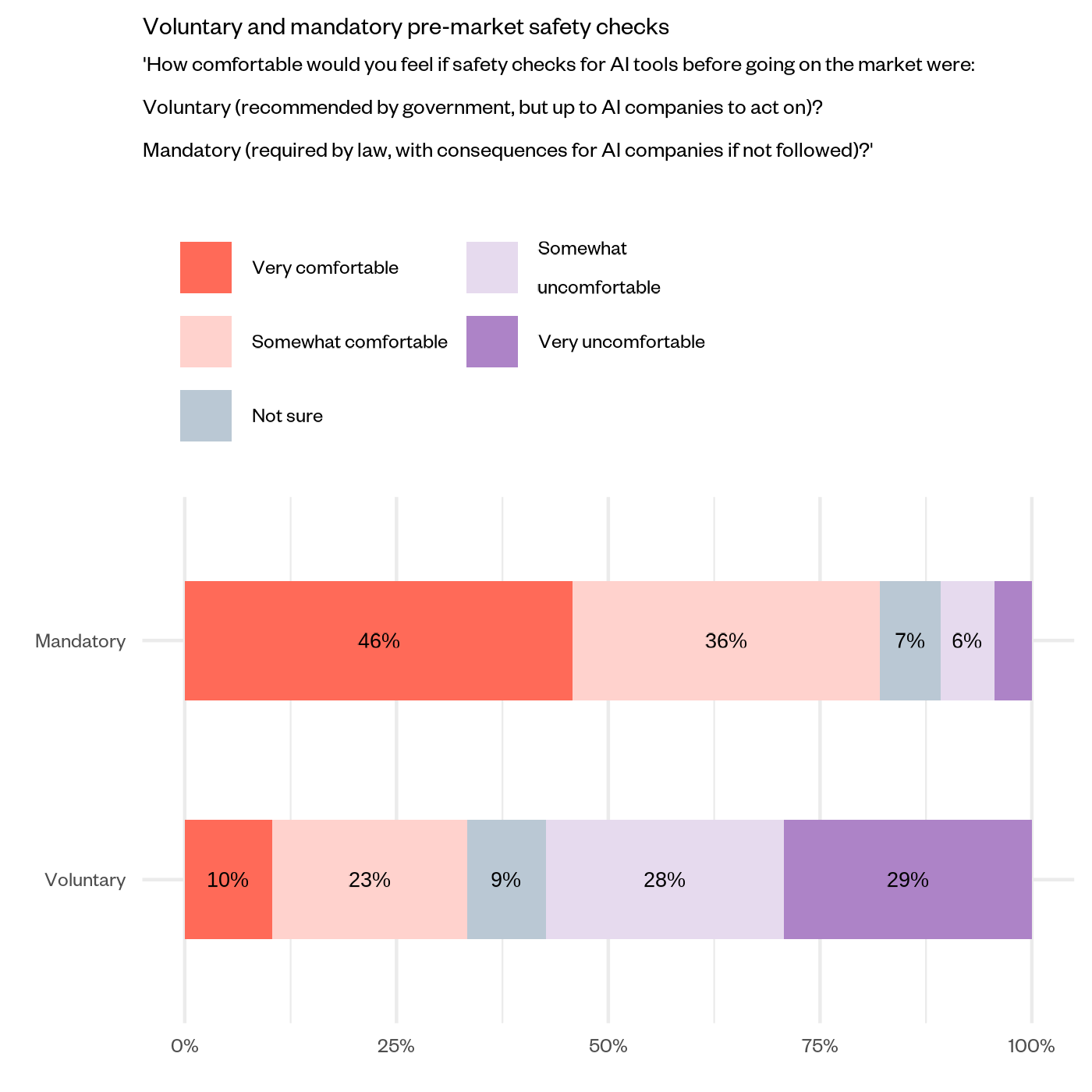

Moreover, the public are considerably more comfortable with mandatory safety checks than with voluntary ones. A large majority of people (82%) support mandatory safety testing, compared to only 33% who feel comfortable with voluntary measures. This aligns with evidence showing that voluntary safety commitments often fail to ensure adequate protections, reinforcing the case for mandatory requirements to safeguard public trust and wellbeing.

Figure 5: Voluntary and mandatory pre-market safety checks

Due to rounding percentages may not total 100%

Demand for transparency and risk reporting

The public also demand greater transparency from AI companies – both with governments and with the public themselves. More than eight in ten people in the UK believe that AI companies should share information with government or regulators. The public support this for known risks of AI systems (86% feel this information should be shared) as well as potential risks (84%). The critical areas they most want to see reported are safety risks (88%), social impacts (80%) and environmental consequences (79%).

Additionally, 85% of people feel that AI companies should share information with the public about the societal costs of AI, including the impact on communities and the environment. 82% believe economic costs, such as energy and resource use, should also be disclosed.

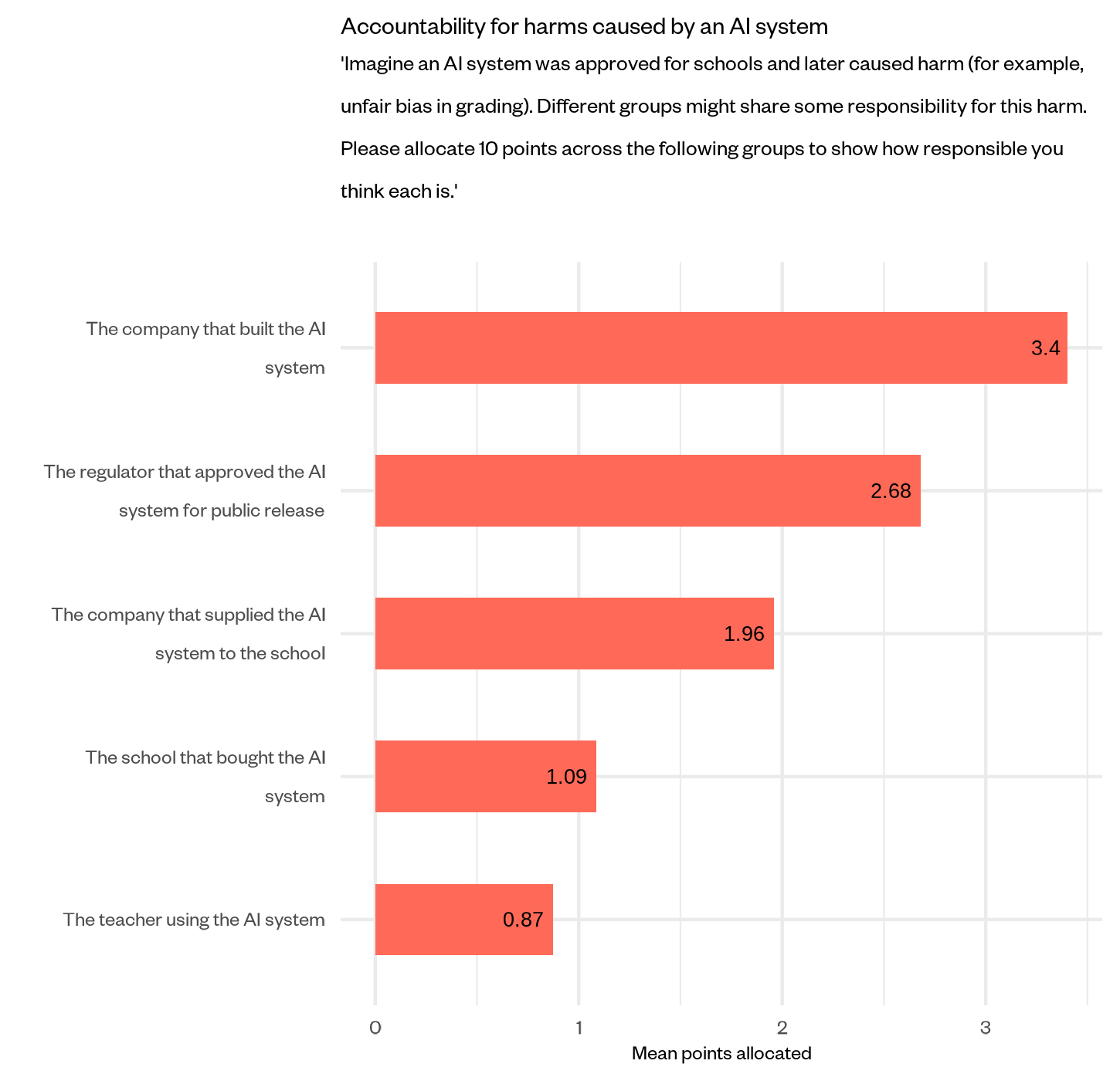

Accountability for harm: AI-enabled grading system used in classrooms

We presented the public with an example of an AI product being used in schools and causing specific harms – in this case, bias in grading. This was to provide the public with a context that felt familiar rather than abstract. They were asked to consider how responsible a set of stakeholders were for this harm.

When considering responsibility for AI-related harms, such as unfair bias in educational settings, the public attribute the greatest accountability to the companies developing AI systems, closely followed by the regulators approving their use. Schools and teachers are seen as bearing minimal responsibility, indicating a preference for a top-down accountability model focused on developers and regulators rather than end-users. This highlights a gap in current legal frameworks, which often lack clear mandates to hold AI developers responsible for harmful outcomes.

Figure 6: Accountability for harms caused by an AI system

Overall, these findings indicate that robust monitoring, mandatory safety testing and clear accountability mechanisms are not just procedural preferences: they are central to building public trust in AI. Without transparent reporting and enforceable responsibility for harm, the public are unlikely to feel confident that AI systems are safe or governed in their interest, risking both societal adoption and the legitimacy of AI governance.

Conclusion

The public expect AI to be developed, deployed and regulated in ways that are safe, transparent and accountable. Currently, neither companies nor regulators are meeting these expectations.

The tables below show how the public expect key questions around AI safety, oversight and accountability to be addressed in an AI Bill. It highlights where people want clear rules, independent regulation and enforceable powers to ensure AI systems are safe and serve the public interest.

Tests for an AI Bill

Who gets to decide what a ‘safe’ AI system looks like?

| What the public say | In numbers |

| Right now, major technology companies developing AI systems set their own standards for what safety means.

There is very little public trust in private companies to act in the best interests of the public, or to effectively deliver on voluntary commitments to carry out safety checks before AI systems are rolled out to the public. In contrast, the majority of the public think it is important that AI is regulated independently, and many believe regulators should have the final say in deciding whether a system is designed and used safely. |

|

Will the government and regulators know what risks AI systems pose before they are deployed?

| What the public say | In numbers |

| Currently in the UK, there is no legal requirement for companies to conduct safety testing of AI systems before they are deployed.

The public strongly support that AI companies conduct safety testing on AI models to ensure that they are safe before they are released to the public. The majority also feel that these pre-market safety checks should be mandatory. |

|

What powers will the government and regulators have to intervene when something goes wrong?

| What the public say | In numbers |

| UK regulators lack the legal authority to compel the modification of AI models or their removal from the market, even when they are linked to serious consequences.

Most of the public feel it is important that the government or regulators have the power to stop the use or sale of an AI system if it is found to cause harm. Powers to take restrictive action (e.g. taking a product off the market) as well as require technical adjustments (e.g. changes to the AI system’s settings) resonate with the public. |

|

Are AI developers and intermediaries (like model hosts) incentivised to manage risks themselves or do they simply pass them on?

| What the public say |

| At present, many AI developers and intermediaries shift liability for the inherent risks of their models onto smaller businesses who purchase and deploy these systems.

The public are uncomfortable with this model of liability and risk management. When asked to consider a scenario involving a school that has procured an AI system for the classroom, the public attribute higher levels of responsibility and accountability to the companies that developed the system, as well as the regulators that approved it, than the schools and teachers using it. Fewer attribute responsibility to schools and teachers. |

Will the government and regulators know the costs of building and using AI, so they can make informed trade-offs about how and when to use it?

| What the public say | In numbers |

| There are currently no legal requirements for companies to disclose the safety, environmental or social impacts of their AI systems to the government, regulators or the public.

This lack of transparency is at odds with public expectations and preferences. The majority feel that AI companies should share information about the potential and known risks of their AI systems with the government and regulators. Most also think the public should be told about the societal and economic costs associated with AI. |

|

Acknowledgements

This policy briefing was lead-authored by Nuala Polo and Roshni Modhvadia, with substantive contributions from Michael Birtwistle, Sohaib Malik, Octavia Field Reid and Catherine Gregory. We would like to thank the team at MEL Research for their contributions in designing the survey and collecting the data for this paper.

Footnotes

[1] The Ada Lovelace Institute commissioned MEL Research to deliver a nationally representative survey of UK adults over the age of 18. Fieldwork took place between 8 and 25 September 2025. We achieved a final sample of 1,928 participants. We used hard, interlocked quotas related to ONS data on region, sex and age, and soft quotas on education, ethnicity and current working status to achieve a broadly nationally representative sample of the UK public. Weighting was also applied to correct for any imbalances across demographic groups. We made efforts to ensure good representation of the UK public but recognise that non-probability sampling methods have limitations, specifically around sampling bias. For instance, in this sample we may be underrepresenting those that are less digitally confident, time poor, or those less connected with the specific networks and channels used at recruitment stages.

Related content

How do people feel about AI? (2025)

Wave two of a nationally representative survey of UK attitudes to AI