Mind the gap: reflections on 2025

Is the ‘AI train’ on the right track?

18 December 2025

Reading time: 9 minutes

Many, many moons ago I worked with local communities across England and very often found myself on trains, on the way to or back from seeing local partners and community groups. On one particularly eventful journey, I was in the first carriage, behind the driver’s compartment. Due to trackside fires, we were in the rather odd situation of hurtling through the British countryside whilst the conductor and train driver scrambled to understand where exactly we might end up. Every so often, passengers were told via intercom that their previously arranged stop was no longer available to them, and they’d have to make do with unscheduled stops at unfamiliar stations or no stop at all.

This vignette has been top-of-mind for me recently. If 2024 was the year that the rubber hit the road for AI, then 2025 has been the year when we have had to ask where exactly the road (or indeed track!) is leading us.

We are being sold the idea that AI-driven progress is a straight, inevitable line and that any doubt, critique or simple evaluation is doom, gloom or defeatist thinking. We are told that those who don’t buy into hype don’t ‘get it’ – that AI is a lightning-fast train (on privately owned infrastructure) that we must catch, lest it passes our stop altogether.

One story I have been hearing a lot, of late, is that AI technologies will follow a linear pathway: from trust, to adoption, to diffusion, to supporting economic growth. This story holds that if the UK public can be encouraged to trust new AI systems and tooling, they will adopt them and trust businesses to do so; if they adopt them at scale, diffusion will follow; and if diffusion occurs, economic growth will – somehow – naturally materialise.

It is an appealing chain of reasoning – one can almost see the theory of change. But its logic doesn’t hold. The relationship between trust and use is far from linear, and the threads linking diffusion to growth, and AI use to productivity are far from evidenced.

For me, 2025 seems to have been a year of unease, of a growing sense that this story of continuous progress may present more culs-de-sac and replacement buses than we are being told and sold. Yes, AI technology is advancing – but is it advancing in ways that work for us, and are we seeing real benefits in the real world?

Great (public) expectations

Our research has shown that AI is a very present reality for most people, with 97% of the UK public having heard or read about it. But far from being reassured by what they hear and read, the public seem uncomfortable and untrusting of both public and private institutions, and that AI tools are being designed with their interest in mind.

A staggering 84% of the UK public think that, when it comes to the regulation of AI, this government will put the interests of big technology companies ahead of the public interest. And when confronted with trade-offs, 89% of the UK public believe that safety is more important than speed and that AI products and services shouldn’t be rolled out until they are safe, even if this means slowing things down. 74% believe that the ability to ban AI on ethical or social grounds is more important than any financial or competitive advantages.

Mind the gap?

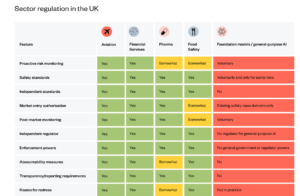

One source of this sense of unease may well be the gap between what the public want and what they are getting. Just as we reported that nearly 9 in 10 people in the UK want independent regulation, UK government officials signalled that they have no intention to move forward with the AI Bill that was promised in the Labour manifesto. This follows a worldwide trend of deregulation, making AI an outlier compared to other consequential sectors and putting people and society at risk of harm.

This is unlikely to get better without concrete action. Our legal analysis in partnership with AWO has found that harms arising from Advanced AI Assistants – which are increasingly embedded in our lives, from our finances to our mental health – are not covered by our current legal system. The risk of sycophantic ‘companion’ chatbots has come to light, painfully, over the last year.

But we are only just beginning to experience the risks these systems might pose – from large-scale influencing of political opinion, to exacerbating social and cognitive deskilling, decreasing human connections and opening up new avenues for market distortion.

And if things do go wrong, our own research of the liability system in the UK has shown that current rules are not sufficient to provide a route to redress, create incentives for risk management, or help clarify legal risks for people and organisations who deploy or use AI. This means that legal and financial risks are likely to be offloaded on those at the end of the supply chain, such as SMEs and local authorities.

The emperor may have new clothes…but do they fit?

Maybe the truth is that the more diffusion we see, the more we strain the narrative of a linear pathway from trust to adoption, to diffusion, to economic growth. And no wonder: we are seeing mass experimentation at scale, and little evidence of concrete benefits outside of labs or very specific use cases.

All the while, gaps are emerging not only in our legal and regulatory systems, but also in our very norms. How many parents feel ready for a future where they need to mediate their children’s relationship with human-like AI companions, especially with embodied AI not far down the track? How many business leaders think that they have their approach to liability sorted, their evaluations pre-defined, and a clear sense of time savings vs. costs, when it comes to real-world use of AI systems – with their company’s reputation, efficacy and bottom line dependent on largely partial information?

Emerging findings from our forthcoming research on the use of AI transcription tools in social work paint an interesting picture. Aiming for promised efficiency gains, local authorities seem to be opting for a ‘try now, test later’ approach. This might be for good reason: the sector is increasingly under pressure, and our (small-scale, qualitative) analysis shows that social workers report that they benefit from using transcription tools.

However, without guidance or clear regulation, we are seeing that there is a real heterogeneity in how these tools are being used, with differing concepts of what ‘appropriate’ use might look like. Oversight and risk management vary significantly – one person’s appropriate ‘human-in-the-loop’ check might take five minutes (if that!), someone else’s might take an hour.

These are not insignificant issues. As with all systems based on generative AI, hallucinations (fabricated references, ‘facts’ and assertions) are more a feature than a bug – not a flaw that can be worked on, but something inherent in their underlying generative architecture. This becomes a problem when these inaccuracies might form part of official records and statutory judgements, with little understanding of how they might be distributed, and growing evidence that ‘LLM-based […] systems […] can exhibit notable biases that lead to discriminatory outcomes in real-world contexts.’

Indeed – as highlighted by a recent LSE study – use cases understood as being largely ‘benign’ such as transcription or summarisation will have significant real-world impacts. In their quantitative analysis of gender bias in LLM-generated case notes from real care records, researchers found that one widely used AI model downplays women’s physical and mental health issues in comparison to men’s. As the author noted, ‘access to social care is determined by perceived need, [so] this could result in unequal care provision for women.’

Is the train running fast, or just runaway?

As we point out in Ada’s 2025-2028 strategy, a global AI ‘arms race’ narrative is skewing our understanding of what is fact and what is fiction in the AI domain. Nation-states are seeking national security and economic advantage through AI development, in a competition that is framed as a zero-sum game between nations. The message we are getting from governments and tech companies alike is that we have to catch this train right now.

Yet our and others’ research is showing that people and businesses are at risk of being left behind. It demonstrates that, if we continue along this track, the laws that protect people and society aren’t and won’t be keeping pace – and that many real-world applications are already falling foul of expectations, leading to allocative (and presumably representational) harm and unintended and unwanted consequences.

Even the UK government’s own AI Security Institute (AISI) has surfaced the limits of soft law and industry-led approaches to standards and evaluation. While AISI’s Frontier AI trends report, published today, shows AI-driven progress in the development of advanced capabilities for certain domains (e.g. cyber, chemistry, biology) some of these capabilities work against the interests of the public. Progress in these cases might mean bolstering cyber criminals, or producing models that are more persuasive, which – according to AISI’s research – can make them less likely to be accurate. This could pose risks to our information economies, how we receive political information and who and what we trust.

As these models advance, the measures to keep people safe are not necessarily progressing at the same pace. AISI found that the safeguards of every system they tested can be broken and advanced models can perform worse than earlier ones when it comes to safety, as ‘more capable models do not necessarily have better safeguards’.

Next stop: a positive vision

So how do we make sure the ‘AI train’ goes in a direction that works for people and society – and not primarily for the most powerful technology companies?

Any high-speed train needs effective brakes and safety features. When it comes to AI, this looks like independent evaluation, audit and assurance supported by a mature, professional field that is plural – rather than in the hands of a few consultancies. It means having evaluation models that translate ethical and rights-based principles into action. And all of this should be grounded in robust, independent regulation.

We also need a clear sense of a destination – and priority seating not just for the government and the tech industry, but for civil society, local authorities, small businesses, and people from all walks of life. To do this, we need to begin to build an inclusive and democratic political vision for what the notion of technology harnessed in the public interest could mean. We also need to better understand how (and if) these technologies actually work in context – from classrooms to hospitals, to workplaces.

At Ada, we will continue to call for AI to be held to the same standards as other consequential sectors like food, medicine and aviation. We will build even more evidence on what we are seeing on the ground and what effective independent regulation could look like. We will convene diverse groups of stakeholders – from civil servants and regulators to industry leaders and technical practitioners – to discuss the complexities of new regulatory frameworks, public benefit, evaluation and infrastructural dependence. And in everything we do, we will centre the hopes, aspirations and fears of diverse publics as AI becomes intertwined with our everyday lives.

Related content

Our strategy

Our strategy highlights the need to understand how AI and data can support a positive vision for society, and the policy choices this will require

Great (public) expectations

New polling shows the public expect AI to be governed with far more rigour than current policy delivers

How can (A)I help?

An exploration of AI assistants

Transcribing trust

Evaluating the use of AI in social care