How ‘open’ is open-source AI?

Exploring how the AI Act regulates open-source AI

23 July 2025

Reading time: 9 minutes

‘Open-source AI’ can be a loaded term. It borrows language from open-source software (OSS) to convey the idea of an AI artefact that can be shared, modified and reproduced with little restrictions on users.

Many AI models, systems and frameworks are equally labelled as open source when they offer different degrees of access. For example, OpenAI’s popular GPT models are accessible only via paid APIs and web interfaces, in contradiction with the company’s name. Meta’s self-proclaimed open-source Llama-3’s licence allows users to download and utilise the model as long as they do not hinder Meta’s business interests. EleutherAI instead provides access to training data, code, model and all components necessary to recreate and modify its GPT-NeoX. Various other AI systems exist partway between these cases of minimal and maximal openness.

Irene Solaiman describes this spectrum of access options as the ‘gradient’ of AI release methods, where different degrees of openness come with specific risks and potential benefits. A very open system may be easier to repurpose, if not fully modify, and its release may be relatively transparent, including information about the data it was trained on. With this degree of access anyone can create a derivative output from the system or its accessible components. In theory, the original programmers should not be held responsible for the harms that may result from such outputs.

OSS has historically had a wide variety of contributors, from individual volunteers to large multinational corporations. In recent years, it has relied more heavily on corporate-employed contributors and firm-driven initiatives, with the boundary between the OSS community and private corporations becoming increasingly porous.

As open-source AI grows in popularity, it is also beginning to be regulated differently from proprietary AI systems. Legislations such as the EU AI Act attempt to mitigate AI harms, while making adjustments to reduce burdens on small and independent open-source projects to foster research and innovation. At this juncture, definitions of open-source AI are becoming increasingly critical to programmers, policymakers and, ultimately, people.

The risks of a binary distinction between open-source and proprietary AI

Public discussions on AI rarely mention the notion of a gradient of openness. Companies like Meta, DeepSeek and EleutherAI contribute to this by using the open-source label as the product of a binary distinction: models can either be open or closed.

This is both confusing and problematic. If the programmers of open-source systems are not liable for the harms cascading from their initial designs, the open-source label could become a get-out-of-jail-free card for corporations who monetise their systems, while opening access to some of their components. If encoded in policy, a binary classification and exemption of liability of open-source AI may create an arbitrary division along the gradient of openness. And those seeking to circumvent regulation might see this as a loophole to exploit.

Policymakers aren’t the only ones struggling with finding appropriate ways to classify the openness of open-source AI. Many online communities and organisations have held public discussions and set up projects to classify the attributes of an open-source AI. The most prominent and most visible of these projects has been the Open Source Initiative (OSI)’s definition.

The OSI’s AI definition

In the 1990s, the OSI formalised and steered the application of the Open Source Definition (OSD), the popular standard determining whether a software licence is open source or not. This has been critical for companies and individuals alike. Open-source licences mean that software is shared without warranty, and people can use it and modify it without worrying about infringing on copyright.

A form of open-source software existed long before the OSI, under the moniker of ‘free software’. In 1998, OSI’s co-founders coined the term ‘open source’ to make the concept more palatable to private companies.

Given the OSI’s reputation for formalising the term and stewarding practices around its use, a general sigh of relief followed the announcement that the initiative would be leading on establishing the Open Source AI Definition (OSAID).

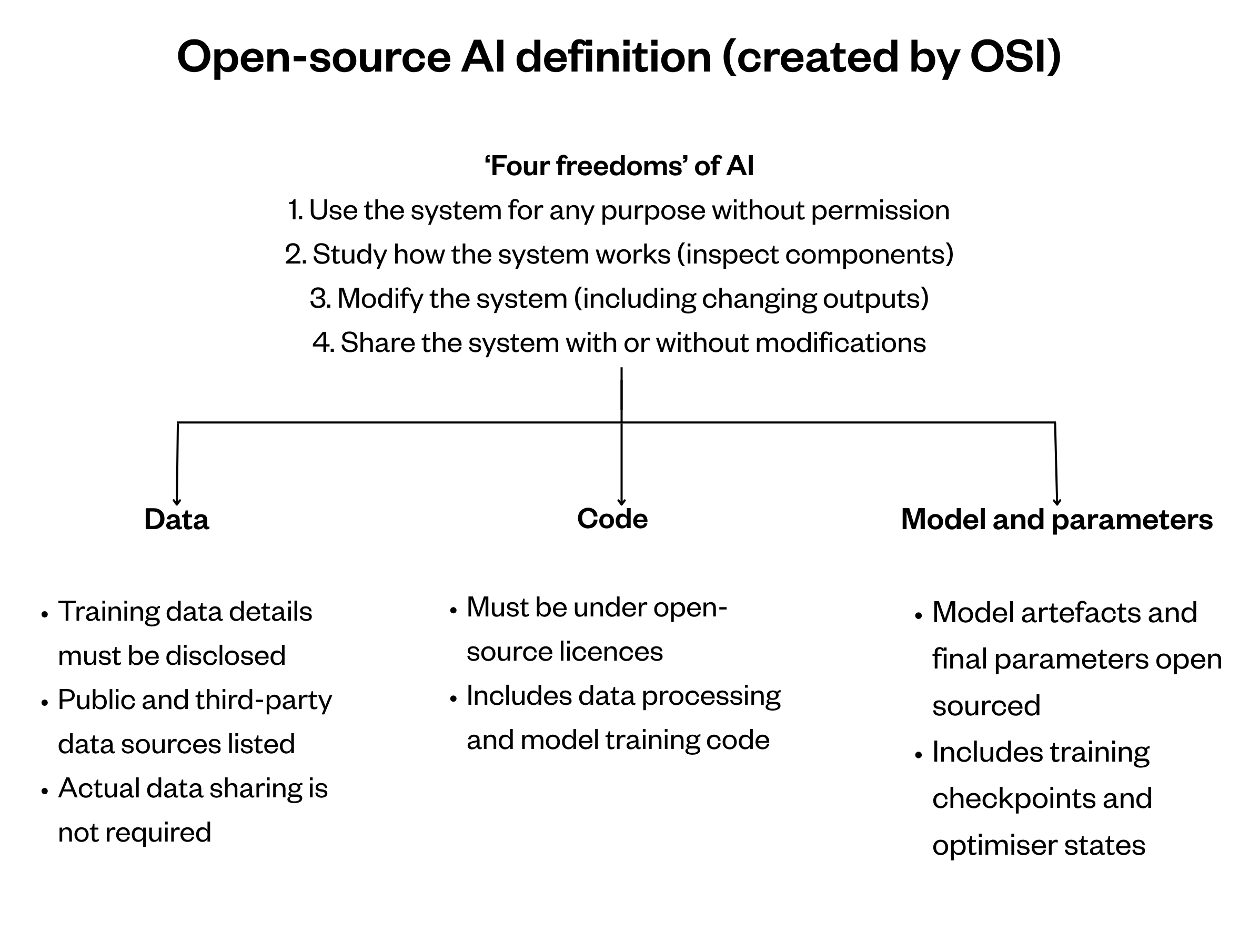

Like the original OSD, the OSAID seeks to qualify what aspects of an AI system grant users the ‘four freedoms’ associated with open source. For a piece of software to be open source, anyone should be able to: use it for any purpose and without having to ask for permission; study how it works and inspect its components; modify it for any purpose, including to change its outputs; and share it for others to use, with or without modifications, for any purpose.

The OSAID draws upon the ‘four freedoms’ to set criteria for the three primary artefacts that constitute an AI system: data, code and model.

Data

The data information that must be shared to fulfil the OSAID is:

- the complete description of all data used for training — including non-shareable data — disclosing its provenance, scope and characteristics, how the data was obtained and selected, the labelling procedures, and data processing and filtering methodologies

- a listing of all publicly available training data and where to obtain it

- a listing of all training data that can be obtained, for free or by paying, from third parties and where to find it.

Access to the actual underlying training or testing data used in the creation of the system is notably absent from this list. The OSAID does not require the data the system is ‘built with’, but only information about such data.

This is a significant omission. A programmer working on a derivative of an OSAID-compliant open-source AI will not be able to modify the data that constitutes the underlying logic of the system, and they will only be able to tweak it by adding new training data. For example, to modify an AI system that, on average, generates a higher number of false identifications for images of racialised people, the programmer will have to add more data, rather than remove or alter the data causing the issue.

This is a tall order for independent and small open-source AI developers, who may simply not have the material resources to retrain a model. If, from a practical perspective, the model cannot be modified, its openness is very limited.

Code

In the case of AI technologies, a system’s code is often responsible for extracting, transforming, and loading the data to train the AI model. Often, it will also include the definitions of parameters – additional technical information on how the model was trained and insights into how the system makes decisions – as well as the application of the trained model to a specific use case. As with any open-source software, the code used for processing data and training the model must be released under an open-source licence.

Model and parameters

The model (the artefact generated by the training process) and its parameter values (the variables that are adjusted during the training) must be released under standard open-source licences as well. The parameter values might include checkpoints from key intermediate stages of training as well as the final optimiser state. These artefacts represent what is generated after the training. They are necessary for the AI system to, for example, make predictions and generate responses to queries, but alone are often insufficient to understand how the AI system is doing what it does.

Exemptions for open-source systems in the EU AI Act

A first testing ground for how the OSAID will intersect AI regulation is the EU AI Act. Are open-source AI systems covered by the Act, or are they exempt? And what does the European legislation consider to be open source?

The regulation seems to offer room for interpretation regarding open-source AI. In this apparent vacuum, third-party organisations like the OSI and their corresponding definitions might assume an informal authority to decide which systems are open source, potentially determining what falls within the legislation’s scope. A relatively soft definition of open source, like the OSAID, which, by omitting requests on training data, does not make AI systems truly reproducible, might weaken the regulation without benefitting the open-source community.

As an example, the Act mentions exemptions for open-source projects in specific areas. One of these refers to AI systems and appears to allow the open-source ones (by which the text of the law seems to mean something similar to a system fulfilling the OSAID) to carry out AI practices that are otherwise listed as prohibited. This provision is meant to support small, independent open-source developers, but would supposedly not apply to systems that could constitute high risk or that carry out prohibited practices and are either ‘placed on the market’ or ‘put into service’. A few questions emerge: does this mean that AI systems in use, but not ‘put into service’ nor ‘placed on the market’ as high-risk products, are fully exempted from the entirety of the EU AI Act? What does it mean to be ‘put into service’, what technological components constitute an open-source AI system, and who is responsible if a third party puts an open-source AI system into service? Will OS models placed on hosting platforms be considered as ‘put into service’?

Notably, another mention of open-source AI in the Act refers to general-purpose AI (GPAI) models, rather than systems. Does this mean that, in this case, the law and all subsequent consultations about it refer only to AI models and their parameters?[1]

In the months and years to come, consultations and case law might bring more clarity to these apparent uncertainties. In the meantime, regulators could support small, independent creators by avoiding a binary use of the notion of open source and consider instead the idea of a spectrum of openness, which better describes existing AI systems and their release strategy by both small and large organisations. The reality of most AI technologies is that they have significantly higher requirements for development than what is traditionally assumed in software development. Therefore, on the one hand, small developers will likely not be able to modify (and benefit from) OSAID-complying systems without access to their training data. On the other hand, regulatory exemptions could end up benefitting mostly larger companies.

Balancing risks and innovation through an open-source regulatory cutout, that might not account for the barriers to independent AI production and the ways in which models enter the market, could create more risk for people, without providing additional opportunity for innovation.

The views expressed in this piece are of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Ada Lovelace Institute.

Footnotes

[1] Recent consultations by the Commission suggest that models that are hosted on platforms such as Hugging Face and GitHub will be considered ‘put into service’. For reference, see: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/faqs/general-purpose-ai-models-ai-act-questions-answers. The producers will be responsible for complying with the Act regarding their model

Image credit: valentinrussanov