Executive summary

‘Where should I go for dinner? What should I read, watch or listen to next? What should I buy?’ To answer these questions, we might go with our gut and trust our intuition. We could ask our friends and family, or turn to expert reviews. Recommendations large and small can come from a variety of sources in our daily lives, but in the last decade there has been a critical change in where they come from and how they’re used.

Recommendations are now a pervasive feature of the digital products we use. We are increasingly living a world of recommendation systems, a type of software designed to sift through vast quantities of data to guide users towards a narrower selection of material, according to a set of criteria chosen by their developers.

Examples of recommendation systems include Netflix’s ‘Watch next’ and Amazon’s ‘Other users also purchased’; TikTok’s recommendation system drives its main content feed.

But what is the risk of a recommendation? As recommendations become more automated and data-driven, the trade-offs in their design and use are becoming more important to understand and evaluate.

Background

This report explores the ethics of recommendation systems as used in public service media organisations. These independent organisations have a mission to inform, educate and entertain the public, and are often funded by and accountable to the public.

In media organisations, producers, editors and journalists have always made implicit and explicit decisions about what to give prominence to, both in terms of what stories to tell and what programmes to commission, but also in how those stories are presented. Deciding what makes the front page, what gets the primetime slot, what makes top billing on the evening news – these are all acts of recommendation. While private media organisations like Netflix primarily use these systems to drive user engagement with their content, public service media organisations, like the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) in the UK, operate with a different set of principles and values.

This report also explores how public service media organisations are addressing the challenge of designing and implementing recommendation systems within the parameters of their mission, and identifies areas for further research into how they can accomplish this goal.

While there is an extensive literature exploring public service values and a separate literature around the ethics and operational challenges of designing and implementing recommendation systems, there are still many gaps in the literature around how public service media organisations are designing and implementing these systems. Addressing these gaps can help ensure that public service media organisations are better able to design these systems. With this in mind, this project has explored the following questions:

- What are the values that public service media organisations adhere to? How do these differ from the goals that private-sector organisations are incentivised to pursue?

- In what contexts do public service media use recommendation systems?

- What value can recommendation systems add for public service media and how do they square with public service values?

- What are the ethical risks that recommendation systems might raise in those contexts? And what challenges should teams consider?

- What are the mitigations that public service media can implement in the design, development, and implementation of these systems?

In answering these questions, we focused on European public service media organisations and in particular on the BBC in the UK, who are project partners on this research.

The BBC is the world’s largest public service media organisation and has been at the forefront of public service broadcasters exploring the use of recommendation systems. As the BBC has historically set precedents that other public service media have followed, it is valuable to understand its work in depth in order to draw wider lessons for the field.

In this report, we explore an in-depth snapshot of the BBC’s development and use of several recommendation systems from summer and autumn 2021, alongside an examination of the work of several other European public service media organisations. We place these examples in the broader context of debates around 21st century public service media and use them to explore the motivations, risks and evaluation of the use of recommendation systems by public service media and their use more broadly.

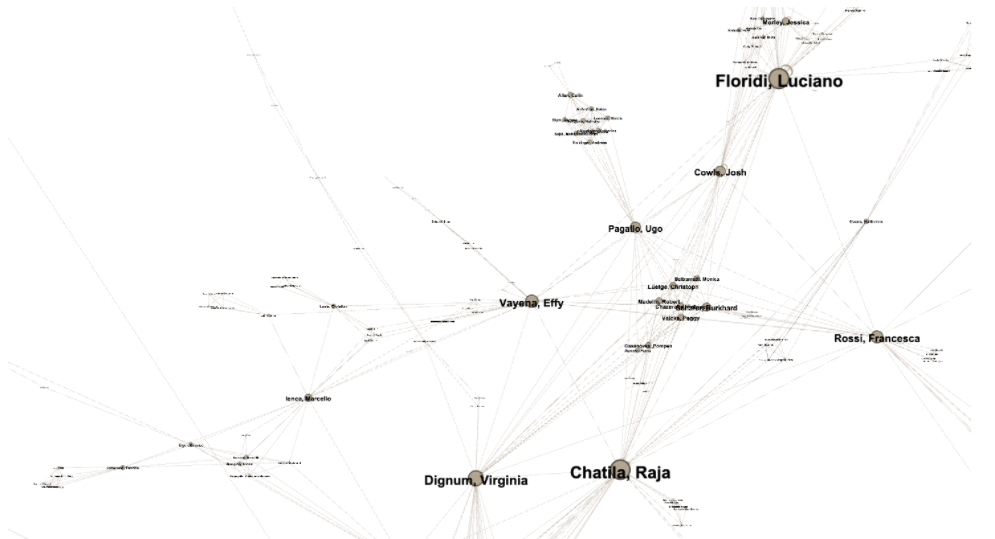

The evidence for this report stems from interviews with 11 current staff from editorial, product and engineering teams involved in recommendation systems at the BBC, along with interviews with representatives of six other European public service broadcasters that use recommendation systems. This report also draws on a review of the existing literature on public service media recommendation systems and on interviews with experts from academia, civil society and government.

Findings

Across these different public service media organisations, our research has found five key findings:

- The contextual role of public service media organisations is a major driver for their increasing use of recommendation systems. The last few decades have seen public service media organisations lose market share of news and entertainment to private providers, putting pressure on public service media organisations to use recommendation systems to stay competitive.

- The values of public service media organisations create different objectives and practices to those in the private sector. While private-sector media organisations are primarily driven to maximise shareholder revenue and market share, with some consideration of social values, public service media organisations are legally mandated to operate with a particular set of public interest values at their core, including universality, independence, excellence, diversity, accountability and innovation.

- These value differences translate into different objectives for the use of recommendation systems. While private firms seek to maximise metrics like user engagement, ‘time on product’ and subscriber retention in the use of their recommendation systems, public service media organisations seek related but different objectives. For example, rather than maximising engagement with recommendation systems, our research found public service media providers want to broaden their reach to a more diverse set of audiences. Rather than maximising time on product, public service media organisations are more concerned with ensuring the product is useful for all members of society, in line with public interest values.

- Public service media recommendation systems can raise a range of well-documented ethical risks, but these will differ depending on the type of system and context of its use. Our research found that public service media recognise a wide array of well-documented ethical risks of recommendation systems, including risks to personal autonomy, privacy, misinformation and fragmentation of the public sphere. However, the type and severity of the risks highlighted depended on which teams we spoke with, with audio-on-demand and video-on-demand teams raising somewhat different concerns to those working on news.

- Evaluating the risks and mitigations of recommendation systems must be done in the context of the wider product. Addressing the risks of public service media recommendation systems should not just focus on technical fixes. Aligning product goals and other product features with public service values are just as important in ensuring recommendation systems positive contribute the experiences of audiences and to wider society.

Recommendations

Based on these key findings, we make nine recommendations for future research, experimentation and collaboration between public service media organisations, academics, funders and regulators:

- Define public service value for the digital age. Recommendation systems are designed to optimise against specific objectives. However, the development and implementation of recommendation systems is happening at a time when the concept of public service value and the role of public service media organisations is under question. Unless public service media organisations are clear about their own identities and purpose, it will be difficult for them to build effective recommendation systems. In the UK, significant work has already been done by Ofcom as well as the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport’s parliamentary Select Committee to identify the challenges public service media face and offer new approaches to regulation. Their recommendations must be implemented so that public service media can operate within a paradigm appropriate to the digital age and build systems that address a relevant mission.

- Fund a public R&D hub for recommendation systems and responsible recommendation challenges. There is a real opportunity to create a hub for R&D of recommendation systems that are not tied to industry goals. This is especially important as recommendation systems are one of the prime use cases of behaviour modification technology but research into it is impaired by lack of access to interventional data. Therefore, as part of UKRI’s National AI Research and Innovation (R&I) Programme set out in the UK AI Strategy, it should fund the development of a public research hub on recommendation technology.

- Publish research into audience expectations of personalisation. There was a striking consensus in our interviews with public service media teams working on recommendations that personalisation was both wanted and expected by the audience. However, there is limited publicly available evidence underlying this belief and more research is needed. Understanding audience’s views towards recommendation systems is an important part of ensuring those systems are acting in the public interest. Public service media organisations should not widely adopt recommendation systems without evidence that they are either wanted or needed by the public. Otherwise, public service media risk simply following a precedent set by commercial competitors, rather than defining a paradigm aligned to their own missions.

- Communicate and be transparent with audiences. Although most public service media organisations profess a commitment to transparency about their use of recommendation systems, in practice there is little effective communication with their audiences about where and how recommendation systems are being used. Public service media should invest time and research into understanding how to usefully and honestly articulate their use of recommendation systems in ways that are meaningful to their audiences. This communication must not be one way. There must be opportunities for audiences to give feedback and interrogate the use of the systems, and raise concerns.

- Balance user control with convenience. Transparency alone is not enough. Giving users agency over the recommendations they see is an important part of responsible recommendation. Simply giving users direct control over the recommendation system is an obvious and important first step, but it is not a universal solution. We recommend that public service media providers experiment with different kinds of options, including enabling algorithmic choice of recommendation systems and ‘joint’ recommendation profiles.

- Expand public participation. Beyond transparency or individual user choice and control over the parameters of the recommendation systems already deployed, users and wider society could also have greater input during the initial design of the recommendation systems and in the subsequent evaluations and iterations. This is particularly salient for public service media organisations as, unlike private companies which are primarily accountable to their customers and shareholders, public service media organisations have an obligation to serve the interests of society. Therefore, even those who are not direct consumers of content should have a say in how public service media recommendations are shaped.

- Standardise metadata. Inconsistent, poor quality metadata – an essential resource for training and developing recommendation systems – was consistently highlighted as a barrier to developing recommendation systems in public service media, particularly in developing more novel approaches that go beyond user engagement and try to create diverse feeds of recommendations. Each public service media organisation should have a central function that standardises the format, creation and maintenance of metadata across the organisation. Institutionalising the collection of metadata and making access to it more transparent across each individual organisation is an important investment in public service media’s future capabilities.

- Create shared recommendation system resources. Given their limited resources and shared interests, public service media organisations should invest more heavily in creating common resources for evaluating and using recommendation systems. This could include a shared repository for evaluating recommendation systems on metrics valued by public service media, including libraries in common coding languages.

- Create and empower integrated teams. When developing and deploying recommendation systems, public service media organisations need to integrate editorial and development teams from the start. This ensures that the goals of the recommendation system are better aligned with the organisation’s goals as a whole and ensure the systems augment and complement existing editorial expertise.

How to read this report

This report examines how European public service media organisations think about using automated recommendation systems for content curation and delivery. It covers the context in which recommendation systems are being deployed, why that matters, the ethical risks and evaluation difficulties posed by these systems and how public service media are attempting to mitigate these risks. It also provides ideas for new approaches to evaluation that could enable better alignment of their systems with public service values.

If you need an introduction or refresher on what recommendation systems are, we recommend starting with the ‘Introducing recommendation systems’.

If you work for a public service media organisation

- We recommend the chapters on ‘Stated goals and potential risks of using recommendation systems in public service media’ and ‘Evaluation of recommendation systems’.

- For an understanding of how the BBC has deployed recommendation systems, see the case studies.

- For ideas on how public service media organisations can advance their responsible use of recommendation systems, see the chapter on ‘Outstanding questions and areas for further research and experimentation’.

If you are a regulator of public service media

- We recommend you pay particular attention to the section on ‘Stated goals and potential risks of using recommendation systems in public service media’ and ‘How do public service media evaluate their recommendation systems?’.

- In addition, to understand the practices and initiatives that we believe should be encouraged within and experimented with by public service media organisations to ensure responsible and effective use of recommendation systems, see ‘Outstanding questions and areas for further research and experimentation’.

If you are a regulator of online platforms

- If you need an introduction or refresher on what recommendation systems are, we recommend starting with the ‘Introducing recommendation systems’. Understanding this context can help disentangle the challenges in regulating recommendation systems, by highlighting where problems arise from the goals of public service media versus the process of recommendation itself.

- To understand the issues faced by all deployers of recommendation systems, see the sections on the ‘Stated goals of recommendation systems’ and ‘Potential risks of using recommendation systems’.

- To better understand how these risks change due to the context and choices of public service media, relative to other online platforms, and the difficulties even organisations explicitly oriented towards public value have in auditing their own recommendation systems to determine whether they are socially beneficial, beyond simple quantitative engagement metrics, see the section on ‘How these risks are viewed and addressed by public service media’ and the chapter on ‘Evaluation of recommendation systems’.

If you are a funder of research into recommendation systems or a researcher interested in recommendation systems

- Public service media organisations, with mandates that emphasise social goals of universality, diversity and innovation over engagement and profit-maximising, can offer an important site of study and experimentation for new approaches to recommendation system design and evaluation. We recommend starting with the sections on ‘The context of public service values and public service media’ and ‘why this matters’, to understand the different context within which public service media organisations operate.

- Then, the sections on ‘How do public service media evaluate their recommendation systems?’ and ‘How could evaluations be done differently?’, followed by the chapter on ‘Outstanding questions and areas for further research and experimentation’, could provide inspiration for future research projects or pilots that you could undertake or fund.

Introduction

Scope

Recommendation systems are tools designed to sift through the vast quantities of data available online and use algorithms to guide users towards a narrower selection of material, according to a set of criteria chosen by their developers. Recommendation systems sit behind a vast array of digital experiences. ‘Other users also purchased…’ on Amazon or ‘Watch next’ on Netflix guide you to your next purchase or night on the sofa. Deliveroo will suggest what to eat, LinkedIn where to work and Facebook who your friends might be.

These practices are credited with driving the success of companies like Netflix and Spotify. But they are also blamed for many of the harms associated with the internet, such as the amplification of harmful content, the polarisation of political viewpoints (although the evidence is mixed and inconclusive)1 and the entrenchment of inequalities.2 Regulators and policymakers worldwide are paying increasing attention to the potential risks of recommendation systems, with proposals in China and Europe to regulate their design, features and uses.3

Public service media organisations are starting to follow the example of their commercial rivals and adopt recommendation systems. Like the big digital streaming service providers, they sit on huge catalogues of news and entertainment content, and can use recommendation systems to direct audiences to particular options.

But public service media organisations face specific challenges in deploying these technologies. Recommendation systems are designed to optimise for certain objectives: a hotel’s website is aiming for maximum bookings, Spotify and Netflix want you to renew your subscription.

Public service media serve many functions. They have a duty to serve the public interest, not the company bottom line. They are independently financed and are controlled by, if not answerable to, the public.4 Their mission is to inform, educate and entertain. Public service media are committed to values including independence, excellence and diversity.5 They must fulfil an array of duties and responsibilities set down in legislation that often predates the digital era. How do you optimise for all that?

Developing recommendation systems for public service media is not just about finding technical fixes. It requires an interrogation of the organisations’ role in democratic societies in the digital age. How do the public service values that have guided them for a century translate to a context where the internet has fragmented the public sphere and audiences are defecting to streaming services? And how can public service media use this technology in ways that serve the public interest?

These are questions that resonate beyond the specifics of public service media organisations. All public institutions that wish to use technologies for societal benefit must grapple with similar issues. And all organisations – public or private – have to deploy technologies in ways that align with their values. Asking these questions can be helpful to technologists more generally.

In a context where the negative impacts of recommendation systems are increasingly apparent, public service media must tread carefully when considering their use. But there is also an opportunity for public service media to do what, historically, it has excelled at – innovating in the public interest.

A public service approach to building recommendation systems that are both engaging and trustworthy could not only address the needs of public service media in the digital age, but provide a benchmark for scrutiny of systems more widely and create a challenge to the paradigm set by commercial operators’ practices.

In this report, we explore how public service media organisations are addressing the challenge of designing and implementing recommendation systems within the parameters of their organisational mission, and identify areas for further research into how they can accomplish this goal.

While there is an extensive literature exploring public service values and a separate literature around the ethics and operational challenges of designing and implementing recommendation systems, there are still many gaps in the literature around how public service media organisations are designing and implementing these systems. Addressing that gap can help ensure that public service media organisations are better able to design these systems. With that in mind, this report explores the following questions:

- What are the values that public service media organisations adhere to? How do these differ from the goals that private-sector organisations are incentivised to pursue?

- In what contexts do public service media use recommendation systems?

- What value can recommendation systems add for public service media and how do they square with public service values?

- What are the ethical risks that recommendation systems might raise in those contexts? And what challenges should different teams within public service media organisations (such as product, editorial, legal and engineering) consider?

- What are the mitigations that public service media can implement in the design, development and implementation of these systems?

In answering these questions, this report:

- provides greater clarity about the ethical challenges that developers of recommendation systems must consider when designing and maintaining these systems

- explores the social benefit of recommendation systems by examining the trade-offs between their stated goals and their potential risks

- provides examples of how public service broadcasters are grappling with these challenges, which can help inform the development of recommendation systems in other contexts.

This report focuses on European public service media organisations and in particular on the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) in the UK, who are project partners on this research. The BBC is the world’s largest public service media organisation and has been at the forefront amongst public service broadcasters of exploring the use of recommendation systems. As the BBC has historically set precedents that other public service media have followed, it is valuable to understand its work in depth in order to draw wider lessons for the field.

In this report, we explore an in-depth snapshot of the BBC’s development and use of several recommendation systems as it stood in 2021, alongside an examination of the work of several other European public service media organisations. We place these examples in the broader context of debates around 21st century public service media and use them to explore the motivations, risks and evaluation of the use of recommendation systems by public service media and their use more broadly.

The evidence for this report stems from interviews with 11 current staff from editorial, product and engineering teams, involved in recommendation systems at the BBC, along with interviews with representatives of six other European public service broadcasters that use recommendation systems. This report also draws on a review of the existing literature on public service media recommendation systems and on interviews with experts from academia, civil society and regulation who work on the design, development, and evaluation of recommendation systems.

Although a large amount of the academic literature focuses on the use of recommendations in news provision, we look at the full range of public service media content, as we found more of the advanced implementations of recommendation systems lie in other domains. We have drawn on published research about recommendation systems from commercial platforms, however, internal corporate studies are unavailable to independent researchers and our requests to interview both researchers and corporate representatives of platforms were unsuccessful.

Background

In this chapter, we set out the context for the rest of the report. We outline the history and context of public service media organisations, what recommendation systems are and how they are approached by public service media organisations, and what external and internal processes and constraints govern their use.

The context of public service values and public service media

The use of recommendation systems in public service media is informed by their history, values and remit, their governance and the landscape in which they operate. In this section we situate the deployment of recommendation systems in this context.

Broadly, public service media are independent organisations that have a mission to inform, educate and entertain. Their values are rooted in the founding vision for public service media organisations a century ago and remain relevant today, codified into regulatory and governance frameworks at organisational, national and European levels. However the values that public service media operate under are inherently qualitative and, even with the existence of extensive guidelines, are interpreted through the daily judgements of public service media staff and the mental models and institutional culture built up over time.

Although public service media have been resilient to change, they currently face a trio of challenges:

- Losing audiences to online digital content providers including Netflix, Amazon, YouTube and Spotify.

- Budget cuts and outdated regulation, framed around analogue broadcast commitments, hampering their ability to respond to technological change.

- Populist political movements undermining their independence.

Public service media are independent media organisations financed by and answerable to the publics they serve.4 Their roots lie in the 1920s technological revolution of radio broadcasting when the BBC was established as the world’s first public service broadcaster, funded by a licence fee, and with the ambition to ‘bring the best of everything to the greatest number of homes’.7 Other national broadcasters were soon founded across Europe and also adopted the BBC’s mission to ‘inform, educate and entertain’. Although there are now public service media organisations in almost every country in the world, this report focuses on European public service media, which share comparable social, political and regulatory developments and therefore a similar context when considering the implementation of recommendation systems.

Public service media organisations have come to play an important institutional role within democratic societies in Europe, creating a bulwark against the potential control of public opinion either by the state or by particular interest groups.8 The establishment of public service broadcasters for the first time created a universally accessible public sphere where, in the words of the BBC’s founding chairman Lord Reith, ‘the genius and the fool, the wealthy and the poor listen simultaneously’. They aimed to forge a collective experience, ‘making the nation as one man’.9 At the same time public service media are expected to reflect the diversity of a nation, enabling the wide representation of perspectives in a democracy, as well as giving people sufficient information and understanding to make decisions on issues of public importance. These two functions create an inherent tension between public service media as an agonistic space where different viewpoints compete and a consensual forum where the nation comes together.

Public service values

The founding vision for public service media has remained within the DNA of organisations as their public service values – often called Reithian principles, in reference to the influence of the BBC’s founding chairman.

The European Broadcasting Union (EBU), the membership organisation for public service media in Europe, has codified the public service mission into six core values: universality, independence, excellence, diversity, accountability and innovation, and member organisations commit to strive to uphold these in practice.5

| Public service value | Meaning |

| Universality | · reach all segments of society, with no-one excluded

· share and express a plurality of views and ideas · create a public sphere, in which all citizens can form their own opinions and ideas, aiming for inclusion and social cohesion · multi-platform · accessible for everyone · enable audiences to engage and participate in a democratic society. |

| Independence | · trustworthy content

· act in the interest of audiences · completely impartial and independent from political, commercial and other influences and ideologies · autonomous in all aspects of the remit such as programming, editorial decision-making, staffing · independence underpinned by safeguards in law. |

| Excellence | · high standards of integrity professionalism and quality; create benchmarks within the media industries

· foster talent · empower, enable and enrich audiences · audiences are also participants. |

| Diversity | · reflect diversity of audiences by being diverse and pluralistic in the genres of programming, the views expressed, and the people employed

· support and seek to give voice to a plurality of competing views – from those with different backgrounds, histories and stories. Help build a more inclusive, less fragmented society. |

| Accountability | · listen to audiences and engage in a permanent and meaningful debate

· publish editorial guidelines. Explain. Correct mistakes. Report on policies, budgets, editorial choices · be transparent and subject to constant public scrutiny · be efficient and managed according to the principles of good governance. |

| Innovation | · enrich the media environment

· be a driving force of innovation and creativity · develop new formats, new technologies, new ways of connectivity with audiences · attract, retain and train our staff so that they can participate in and shape the digital future, serving the public. |

As well as signing up to these common values, each individual public service media organisation has its own articulation of its mission, purpose and values, often set out as part of its governance.11 Ultimately these will align with those described by the EBU but may use different terms or have a different emphasis. Policymakers and practitioners operating at a national level are more likely to refer to these specific expressions of public values. The overarching EBU values are often referenced in academic literature as the theoretical benchmark for public service values.

In the case of the BBC, the Royal Charter between the Government and the BBC is agreed for a 10 year period.12

The BBC: governance and values

Mission: to act in the public interest, serving all audiences through the provision of impartial, high-quality and distinctive output and services which inform, educate and entertain.

Public purposes:

- To provide impartial news and information to help people understand and engage with the world around them.

- To support learning for people of all ages.

- To show the most creative, highest quality and distinctive output and services.

- To reflect, represent and serve the diverse communities of all of the United Kingdom’s nations and regions and, in doing so, support the creative economy across the United Kingdom.

- To reflect the United Kingdom, its culture and values to the world.

Additionally, the BBC has its own set of organisational values that are not part of the governance agreement but that ‘represent the expectations we have for ourselves and each other, they guide our day-to-day decisions and the way we behave’:

- Trust: Trust is the foundation of the BBC – we’re independent, impartial and truthful.

- Respect: We respect each other – we’re kind, and we champion inclusivity.

- Creativity: Creativity is the lifeblood of our organisation.

- Audiences: Audiences are at the heart of everything we do.

- One BBC: We are One BBC – we collaborate, learn and grow together.

- Accountability: We are accountable and deliver work of the highest quality.

These kinds of regulatory requirements and values are then operationalised internally through organisations’ editorial guidelines which again will vary from organisation to organisation, depending on the norms and expectations of their publics. Guidelines can be extensive and their aim is to help teams put public service values into practice. For example, the current BBC guidelines run to 220 pages, covering everything from how to run a competition, to reporting on wars and acts of terror.

Nonetheless, such guidelines leave a lot of room for interpretation. Public service values are, by their nature, qualitative and difficult to measure objectively. For instance, consider the BBC guidelines on impartiality – an obligation that all regulated broadcasters in the UK must uphold – and over which the BBC has faced intense scrutiny:

‘The BBC is committed to achieving due impartiality in all its output. This commitment is fundamental to our reputation, our values and the trust of audiences. The term “due” means that the impartiality must be adequate and appropriate to the output, taking account of the subject and nature of the content, the likely audience expectation and any signposting that may influence that expectation.’

‘Due impartiality usually involves more than a simple matter of ‘balance’ between opposing viewpoints. We must be inclusive, considering the broad perspective and ensuring that the existence of a range of views is appropriately reflected. It does not require absolute neutrality on every issue or detachment from fundamental democratic principles, such as the right to vote, freedom of expression and the rule of law. We are committed to reflecting a wide range of subject matter and perspectives across our output as a whole and over an appropriate timeframe so that no significant strand of thought is under-represented or omitted.’

It’s clear that impartiality is a question of judgement and may not even be expressed in a single piece of content but over the range of BBC output over a period of time. In practice, teams internalise these expectations and make decisions based on institutional culture and internal mental models of public service value, rather than continually checking the editorial guidelines or referencing any specific public values matrix.13

How public service media differ from other media organisations

Public service media are answerable to the publics they serve.14 They should be independent from both government influence and from the influence of commercial owners. They operate to serve the public interest.

Commercial media, however, serve the interests of their owners or shareholders. Success for Netflix for example is measured in numbers of subscribers which then translates into revenues.15

The activities of commercial media are nonetheless limited by regulation. In the UK the independent regulator Ofcom’s Broadcasting Code requires all broadcasters (not just public service media) to abide by principles such as fairness and impartiality.16 Russia Today for example has been investigated for allegedly misleading reporting on the conflict in Ukraine.17 Streaming services are subject to more limited regulation which covers child protection, incitement to hatred and product placement,18 while the press – both online and in print – are largely lightly self-regulated through the Independent Press Standards Organisation, with some publications regulated by IMPRESS.19

However, public service media have extensive additional obligations, amongst others to ‘meet the needs and satisfy the interests of as many different audiences as practicable’ and ‘reflect the lives and concerns of different communities and cultural interests and traditions within the United Kingdom, and locally in different parts of the United Kingdom’,20

These regulatory systems vary from country to country but hold broadly the same characteristics. In all cases, the public service remit entails far greater duties than in the private sector and broadcasters are more heavily regulated than digital providers.

These obligations are also framed in terms of public or societal benefit. This means public service media are striving to achieve societal goals that may not be aligned with a pure maximisation of profits, while commercial media pursue interests more aligned with revenue and the interests of their shareholders.

Nonetheless, public service media face scrutiny about how well they meet their objectives and have had to create proxies for these intangible goals to demonstrate their value to society.

‘[Public service media] is fraught today with political contention. It must justify its existence and many of its efforts to governments that are sometimes quite hostile, and to special interest groups and even competitors. Measuring public value in economic terms is therefore a focus of existential importance; like it or not diverse accountability processes and assessment are a necessity.’21

In practice this means public service media organisations measure their services against a range of hard metrics, such as audience reach and value for money, as well as softer measures like audience satisfaction surveys.22 In the mid-2000s the BBC developed a public value test to inform strategic decisions that has since been adopted as a public interest test which remains part of the BBC’s governance. Similar processes have been created in other public service media systems, such as the ‘Three Step Test’ in German broadcasting.23 These methods have their own limitations, drawing public media into a paradigm of cost-benefit analysis and market fixing, rather than articulating wider values to individuals, society and industry.13

This does not mean commercial media are devoid of values. Spotify for example says its mission ‘is to unlock the potential of human creativity—by giving a million creative artists the opportunity to live off their art and billions of fans the opportunity to enjoy and be inspired by it’,25 while Netflix’s organisational values are judgment, communication, curiosity, courage, passion, selflessness, innovation, inclusion, integrity and impact.26 Commercial media are also sensitive to issues that present reputational risk, for instance the outcry over Joe Rogan’s Spotify podcast propagating disinformation about COVID-19 or Jimmy Carr’s joke about the Holocaust.27

However, commercial media harness values in service of their business model, whereas for public service media the values themselves are the organisational objective. Therefore, while the ultimate goal of a commercial media organisation is quantitative (revenue) the ultimate goal of public service media is qualitative (public value) – even if this is converted into quantitative proxies.

This difference between public and private media companies is fundamental in how they adopt recommendation systems. We discuss this further later in the report when examining the objectives of using recommendation systems.

Current challenges for public service media

Since their inception, public service media and their values have been tested and reinterpreted in response to new technologies.

The introduction of the BBC Light Programme in 1945, a light entertainment alternative to the serious fare offered by the BBC Home Service, challenged the principle of universality (not everyone was listening to the same content at the same time) as well as the balance between the mission to inform, educate and entertain (should public service broadcasting give people what they want or what they need?). The arrival of the video recorder, and then new channels and platforms, gave audiences an option to opt out of the curated broadcast schedule –where editors determined what should be consumed. While this enabled more and more personalised and asynchronous listening and viewing, it potentially reduced exposure to the serendipitous and diverse content that is often considered vital to the public service remit.28 The arrival and now dominance of digital technologies comes amid a collision of simultaneous challenges which, in combination, may be existential.

Audience

Public service media have always had a hybrid role. They are obliged to serve the public simultaneously as citizens and consumers.29

Their public service mandate requires them to produce content and serve audiences that the commercial market does not provide for. At the same time, their duty to provide a universal service means they must aim to reach a sizeable mainstream audience and be active participants in the competitive commercial market.

Although people continue to use and value public service media, the arrival of streaming services such as Netflix, Amazon and Spotify, as well as the availability of content on YouTube, has had a massive impact on public service media audience share.

In the UK, the COVID-19 pandemic has seen people return to public service media as a source of trusted information, and with more time at home they have also consumed more public service content.30

But lockdowns also supercharged the uptake of streaming. By September 2020, 60% of all UK households subscribed to an on-demand service, up from 49% a year earlier. Just under half (47%) of all adults who go online now consider online services to be their main way of watching TV and films, rising to around two-thirds (64%) among 18–24 year olds.31

Public service media are particularly concerned about their failure to reach younger audiences.32 Although this group still encounters public service media content, they tend to do so on external services: younger viewers (16–34 year olds) are more likely to watch BBC content on subscription video-on-demand (SVoD) services rather than through BBC iPlayer (4.7 minutes per day on SVoD vs. 2.5 minutes per day on iPlayer).31 They are not necessarily aware of the source of the content and do not create an emotional connection with the public service media as a trusted brand. Meanwhile, platforms gain valuable audience insight data through this consumption which they do not pass onto the public service media organisations.34

Regulation

Legislation has not kept pace with the rate of technological change. Public service media are trying to grapple with the dynamics of the competitive digital landscape on stagnant or declining budgets, while continuing to meet their obligations to provide linear TV and radio broadcasting to a still substantial legacy audience.

The UK broadcasting regulator Ofcom published recommendations in 2021, repeating its previous demands for an urgent update to the public service media system to make it sustainable for the future. These include modernising the public service objectives, changing licences to apply across broadcast and online services and allowing greater flexibility in commissioning across platforms.31

The Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Select Committee of the House of Commons has also demanded regulatory change. It warned that ‘hurdles such as the Public Interest Test inhibit the ability of [public service broadcasters] to be agile and innovate at speed in order to compete with other online services’ and that the core principle of universality would be threatened unless public service media were better able to attract younger audiences.34

Although there has been a great deal of activity around other elements of technology regulation, particularly the Online Safety Bill in the UK and the Digital Services Act in the European Union, the regulation of public service media has not been treated with the same urgency. There is so far no Government white paper for a promised Media Bill that would address this in the UK and the European Commission’s proposals for a European Media Freedom Act are in the early stages of consultation.37

Political context

Public service media have always been a political battleground and have often had fractious relationships with the government of the day. But the rise of populist political movements and governments has created new fault lines and made public service media a battlefield in the culture wars. The Polish and Hungarian Governments have moved to undermine the independence of public service media, while the far-right AfD party in eastern Germany refused to approve funding for public broadcasting.38 In the UK, the Government has frozen the licence fee for two years and has said future funding arrangements are ‘up for discussion’. It has also been accused of trying to appoint an ideological ally to lead the independent media regulator Ofcom. Elsewhere in Europe, journalists from public service media have been attacked by anti-immigrant and COVID-denial protesters.39

At the same time, public service media are criticised as unrepresentative of the publics they are supposed to serve. In the UK, both the BBC and Channel 4 have attempted to address this by moving parts of their workforce out of London.40 As social media has removed traditional gatekeepers to the public sphere, there is less acceptance of and deference towards the judgement of media decision-makers. In a fragmented public sphere, it becomes harder for public service media to ‘hold the ring’ – on issues like Brexit, COVID-19, race and transgender rights, public service media find themselves distrusted by both sides of the argument.

Although the provision of information and educational resources through the COVID-19 pandemic has given public service media a boost, both in audiences and in levels of trust, they can no longer take their societal value or even their continued existence for granted.30 Since the arrival of the internet, their monopoly on disseminating real-time information to a wide public has been broken and so their role in both the media and democratic landscape is up for grabs.42 For some, this means public service media is redundant.43 For others, its function should now be to uphold national culture and distinctiveness in the face of the global hegemony of US-owned platforms.44

The Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose has proposed reimagining the BBC as a ‘market shaper’ rather than a market fixer, based on a concept of dynamic public value,13 while the Media Reform Coalition calls for the creation of a Media Commons of independent, democratic and accountable media organisations, including a People’s BBC and Channel 4.46 The wide range of ideas in play demonstrates how open the possible futures of public service media could be.

Introducing recommendation systems

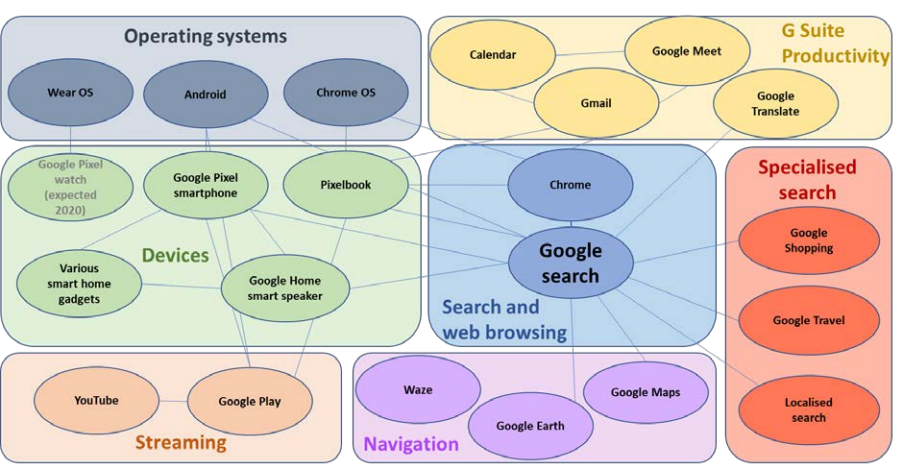

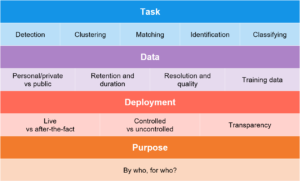

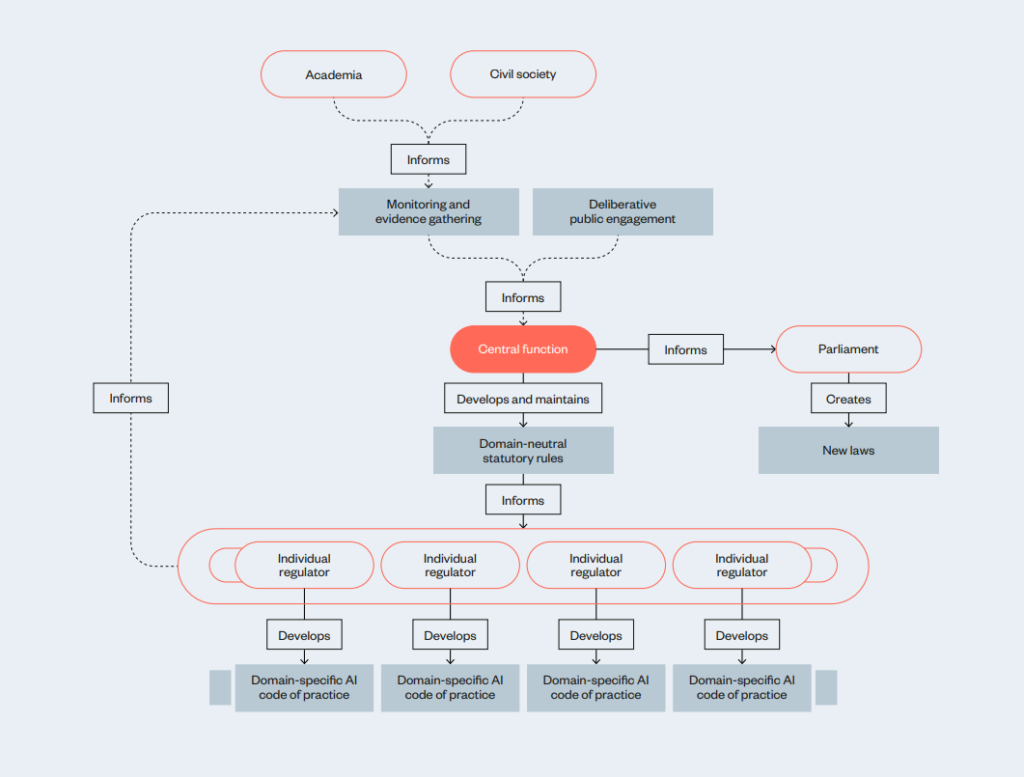

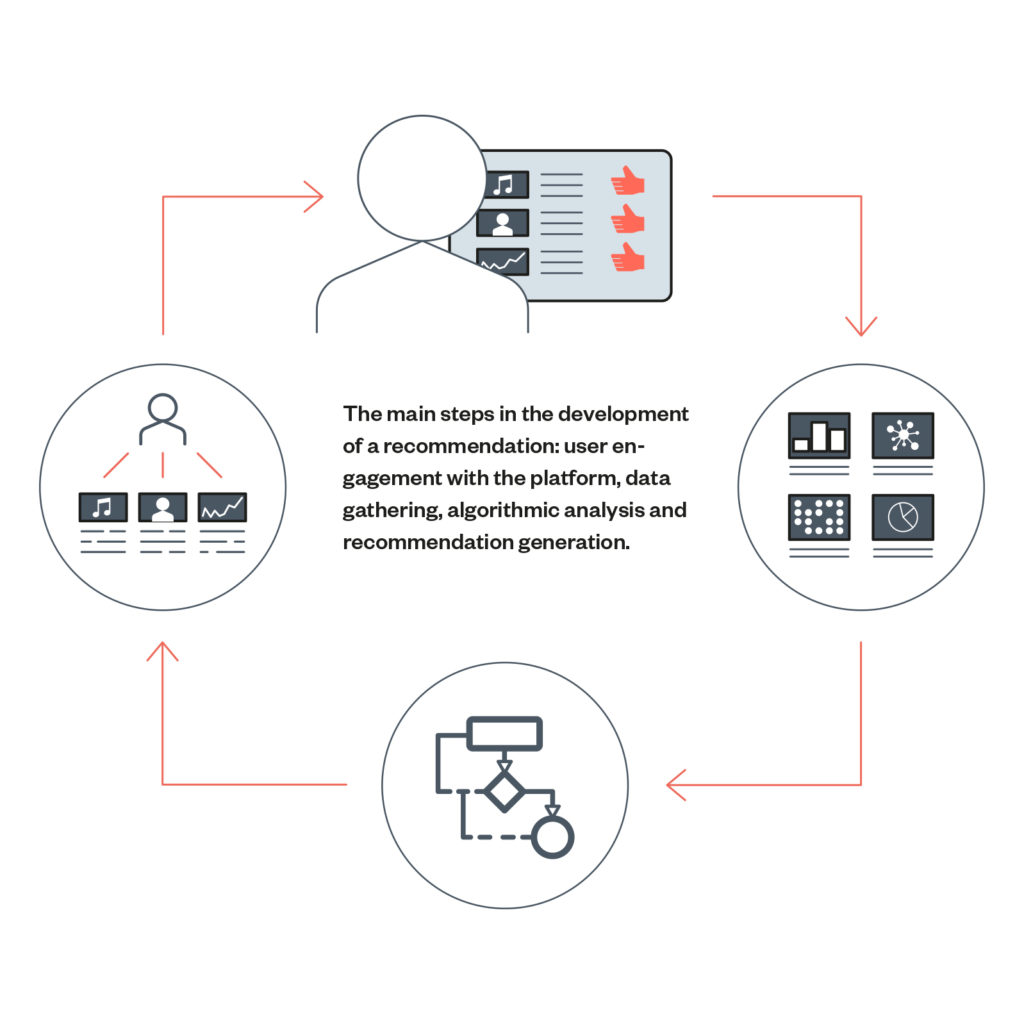

The main steps in the development of a recommendation: user engagement with the platform, data gathering, algorithmic analysis and recommendation generation.

Day-to-day, we might turn to friends or family for their recommendations when it comes to decisions large and small. From dining out and entertainment, to big purchases. We might also look at expert reviews. But in the last decade, there has been a critical change in where recommendations come from and how they’re used. Recommendations have now become a pervasive feature of the digital products we use.

Recommendation systems are a type of software that filter information based on contextual data and according to criteria set by its designers. In this section, we briefly outline how recommendation systems operate and how they are used in practice by European public service media. At least a quarter of European public service media have begun deploying recommendation systems. They are mainly used on video platforms but they are only applied on small sections of services – the vast majority of public service content continues to be manually curated by editors.

In media organisations, producers, editors and journalists have always made implicit and explicit decisions about what to give prominence to, from what stories to tell and what programmes to commission, to – just as importantly – how those stories are presented. Deciding what makes the front page, what gets prime time, what makes top billing on the evening news – these are all acts of recommendation. For some, the entire institution is a system for recommending content to their audiences.

Public service media organisations are starting to automate these decisions by using recommendation systems.

Recommendation systems are context-driven information filtering systems. They don’t use explicit search queries from the user (unlike search engines) and instead rank content based only on contextual information.47

This can include:

- the item being viewed, e.g. the current webpage, the article being read, the video that just finished playing etc.

- the item being filtered and recommended, e.g. the length of the content, when the content was published, characteristics of the content, e.g. drama, sport, news – often described as metadata about the content

- the users, e.g. their location or language preferences, their past interactions with the recommendation system etc.

- the wider environment, e.g. the time of day.

Examples of well-known products utilising recommendation systems include:

- Netflix’s homepage

- Spotify’s auto-generated playlists and auto-play features

- Facebook’s ‘People You May Know’ and ‘News Feed’

- YouTube’s video recommendations

- TikTok’s ‘For You’ page

- Amazon’s ‘Recommended For You’, ‘Frequently Bought Together’, ‘Items Recently Viewed’, ‘Customers Who Bought This Item Also Bought’, ‘Best-Selling’ etc.48

- Tinder’s swiping page49

- LinkedIn’s ‘Recommend for you’ jobs page.

- Deliveroo or UberEats’ ‘recommended’ sort for restaurants.

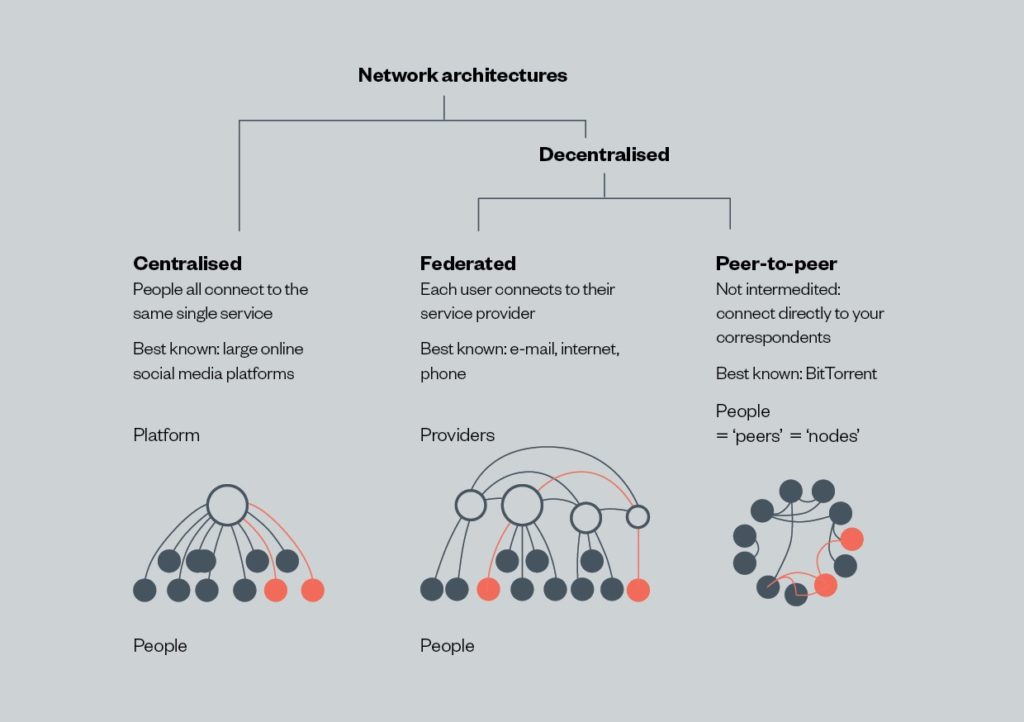

Recommendation systems and search engines

It is worth acknowledging the difference between recommendation systems and search engines, which can be thought of as query-driven information filtering systems. They filter, rank and display webpages, images and other items primarily in response to a query from a user (such as Google searching for ‘restaurants near me’). This is then often combined with the contextual information mentioned above. Google Search is the archetypal search engine in most Western countries but other widely used search engines include Yandex, Baidu and Yahoo. Many public service media organisations offer a query-driven search feature on their services that enables users to search for news stories or entertainment content.

In this report, we have chosen to focus on recommendation systems rather than search engines as the context-driven rather than query-driven approach of recommendation systems is much more analogous to traditional human editorial judgment and content curation.

Broadly speaking, recommendation systems take a series of inputs, filter and select which ones are most important, and produce an output (the recommendation). The inputs and outputs of recommendation systems are subject to content moderation (in which the pool of content is pre-screened and filtered) and curation (in which content is selected, organised and presented).

This starts by deciding what to input into the recommendation system. The pool of content to draw from is often dictated by the nature of the platform itself, such as activity from your friends, groups, events, etc. alongside adverts, as in the case of Facebook. In the case of public service media, the pool of content is often their back catalogue of audio, video or news content.

This content will have been moderated in some way before it reaches the recommendation system, either manually by human moderators or editors, or automatically through software tools. On Facebook, this means attempts to remove inappropriate user content, such as misinformation or hate speech, from the platform entirely, according to moderation guidelines. For a public service media organisation, this will happen in the commissioning and editing of articles, radio programmes and TV shows by producers and editorial teams.

The pool of content will then be further curated as it moves through the recommendation system, as certain pieces of content might be deemed appropriate to publish but not to recommend in a particular context, e.g. Facebook might want to avoiding recommending you posts in languages you don’t speak. In the case of public service media, this generally takes the form of business rules, which are editorial guidelines implemented directly into the recommendation system.

Some business rules apply equally across all users and further constrain the set of content that the system recommends content from, such as only selecting content from the past few weeks. Other rules apply after individual user recommendations have been generated and filter those recommendations based on specific information about the user’s context, such as not recommending content the user has already consumed.

For example, below are business rules that were implemented in BBC Sounds’ Xantus recommendation system, as of summer 2021:50

| Non-personalised business rules | Personalised business rules |

| Recency | Already seen items |

| Availability | Local radio (if not consumed previously) |

| Excluded ‘master brands’, e.g., particular radio channels51 | Specific language (if not consumed previously) |

| Excluded genres | Episode picking from a series |

| Diversification (1 episode per brand/series) |

How different types of recommendation systems work

Not all recommendation systems are the same. One major difference relates to what categories of items a system is filtering and curating for. This can include, but isn’t limited to:

- content, e.g. news articles, comments, user posts, podcasts, songs, short-form video, long-form video, movies, images etc. or any combination of these content types

- people, e.g. dating app profiles, Facebook profiles, Twitter accounts etc.

- metadata, e.g. the time, data, location, category etc. of a piece of content or the age, gender, location etc. of a person.

In this report, we mainly focus on:

- Media content recommendation systems: these systems rank and display pieces of media content, e.g. news articles, podcasts, short-form videos, radio shows, television shows, movies etc. to users of news websites, video-on-demand and streaming services, music and podcast apps etc.

- Media content metadata recommendation systems: these rank and display suggestions for information to classify pieces of media content, e.g. genre, people or places which appear in the piece of media, or other tags, to journalists, editors or other members of staff at media organisations.

Another important distinction between applications of recommendation systems is the role of the provider in choosing which set of items the recommendation system is applied to. There are three categories of use for recommendation systems:

- Open recommending: The recommendation system operates primarily on items that are generated by users of the platform, or otherwise indiscriminately automatically aggregated from other sources, without the platform curating or individually approving the items. Examples include YouTube, TikTok’s ‘For You’ page, Facebook’s ‘News Feed’ and many dating apps.

- Curated recommending: The recommendation system operates on items which are curated, approved or otherwise editorialised by the platform operating the recommendation system. These systems still primarily rely on items generated by external sources, sometimes blended with items produced by the platform. Often these external items will come in the form of licensed or syndicated content such as music, films, TV shows, etc. rather than user-generated items. Examples include Netflix, Spotify and Disney+.

- Closed recommending: The recommendation system operates exclusively on items generated or commissioned by the platform operating the recommendation system. Examples include most recommendation systems used on the website of news organisations.

Lastly, there are different types of technical approaches that a recommendation system may use to sort and filter content. The approaches detailed below are not mutually exclusive and can be combined in recommendation systems in particular contexts:

| Type of filtering | Example | What does it do? |

| Collaborative filtering | ‘Customers Who Bought This Item Also Bought’ on Amazon | The system recommends items to users based on the past interactions and preferences of other users who are classified as having similar past interactions and preferences. These patterns of behaviour from other users are used to predict how the user seeing the recommendation would rate new items. Those item rating predictions are used to generate recommendations of items that have a high level of similarity with content previously popular with similar users. |

| Matrix factorisation | Netflix’s ‘Watch Next’ feature | A subclass of collaborative filtering, this method codifies users and items into a small set of categories based on all the user ratings in a system. When Netflix recommends movies, a user may be codified by how much they like action, comedy, etc. and a movie might be codified by how much it fits into these genres. This codified representation can then be used to guess how much a user will like a movie they haven’t seen before, based on whether these codified summaries ‘match’.

|

| Content-based filtering | Netflix’s ‘Action Movies’ list | These methods recommend items based on the codified properties of the item stored in the database. If the profile of items a user likes mostly consists of action films, the system will recommend other items that are tagged as action films. The system does not draw on user data or behaviour to make recommendations. |

Of these typologies, the public service media that we surveyed only use closed recommendation systems as they are applying recommendations to content they have commissioned or produced. However, we found examples of public service media using all types of filtering approaches: collaborative filtering, content-based filtering and hybrid recommendation systems.

How do European public service media organisations use recommendation systems?

The use of recommendation systems is common but not ubiquitous among public service media organisations in Europe. As of 2021, at least a quarter of European Broadcasting Union (EBU) member organisations were using recommendation systems on at least one of their content delivery platforms.52 Video-on-demand platforms are the most common use case for recommendation systems, followed by audio-on-demand and news content. As well as these public-facing recommendation systems, some public service media also use recommendation systems for internal-only purposes, such as systems that assist journalists and producers with archival research.53

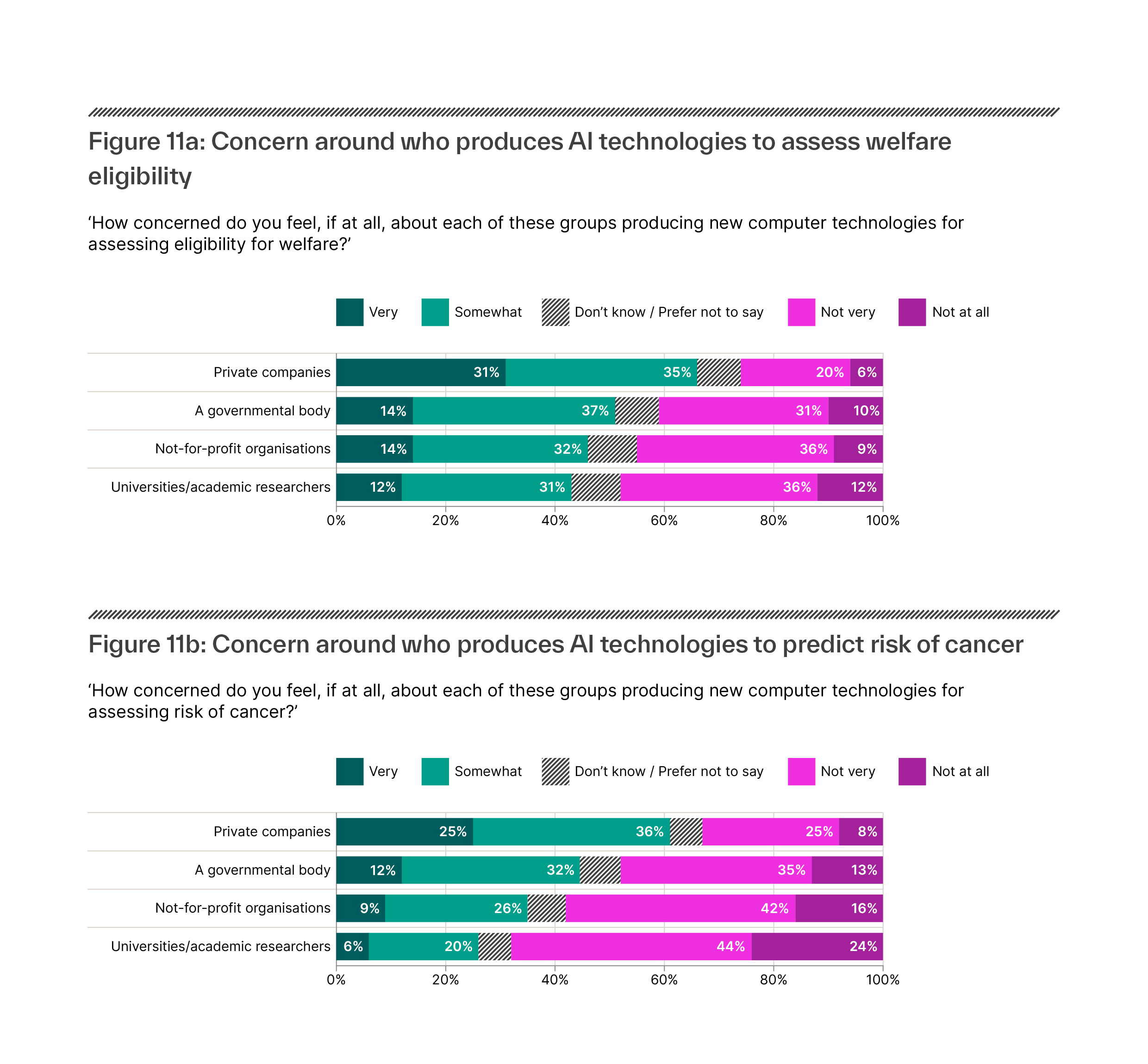

Figure 1: Recommendation system use by European public service media by platform (EBU, 2020)

| Platform on which public service media offers personalised recommendations | Number of European Broadcasting Union member organisations | Examples |

| Video-on-demand | At least 18 | BBC iPlayer |

| Audio-on-demand | At least 10 | BBC Sounds, ARD Audiothek |

| News content | At least 7 | VRT NWS app |

Among the EBU member organisations which reported using recommendation systems in a 2020 survey, recommendations were displayed:

- in a dedicated section on the on-demand homepage (by at least 16 organisations)

- in the player as ‘play next’ suggestions (by at least 10 organisations)

- as ‘top picks’ on the on-demand homepage (by at least 9 organisations).

Even among organisations that have adopted recommendation systems, their use remains very limited. NPO in the Netherlands was the only organisation we encountered that aims to have a fully algorithmically driven homepage on its main platform. In most cases, the vast majority of content remains under human editorial control, with only small sub-sections of the interface offering recommended content.

As editorial independence is a key public service value, as well as a differentiator of public service media from its private-sector competitors, it is likely most public service media will retain a significant element of curation. The requirement for universality also creates a strong incentive to ensure that there is a substantial foundation of shared information to which everyone in society should be exposed.

Recommendation systems in the BBC

The BBC is significantly larger in staff, output and audience than other European public service media organisations. It has a substantial research and development department and has been exploring the use of recommendation systems across a range of initiatives since 2008.54

In 2017, the BBC Datalab was established with the aim of helping audiences discover relevant content by bringing together data from across the BBC, augmented machine learning and editorial expertise.55 It was envisioned as a central capability across the whole of the BBC (TV, radio, news and web) which would build a data platform for other BBC teams that would create consistent and relevant experiences for audiences across different products. In practice, this has meant collaborating with different product teams to develop recommendation systems.

The BBC now uses several recommendation systems, at different degrees of maturity, across different forms of media, including:

- written content, e.g. the BBC News app and some international news services, such as the Spanish-language BBC Mundo, recommending additional new stories56

- audio-on-demand, e.g. BBC Sounds recommending radio programmes and music mixes a user might like

- short-form video, e.g. BBC Sport and BBC+ (now discontinued) recommending videos the user might like

- long-form video, e.g. BBC iPlayer recommending TV shows or films the user might like.

Approaches to the development of recommendation systems

Public service media organisations have the choice to buy an external ‘off the shelf’ recommendation system or build it themselves.

The BBC initially used third-party providers of recommendation systems but, as part of a wider review of online services, began to test the pros and cons of bringing this function in-house. Building on years of their own R&D work, the BBC found they were able to build a recommendation system that not only matched but could outperform the bought-in systems. Once it was clear that personalisation would be central to the future strategy of the BBC, they decided to bring all systems in-house with the aim of being ‘in control of their destiny’.57 The perceived benefits include building up technical capability and understanding within the organisation, better control and integration of editorial teams, better alignment with public service values and greater opportunity to experiment in the future.58

The BBC has far greater budgets and expertise than most other public service media organisations to experiment with and develop recommendation systems. But many other organisations have also chosen to build their own products. Dutch broadcaster NPO has a small team of only four or five data scientists, focused on building ‘smart but simple’ recommendations in-house, having found third-party products did not cater to their needs. It is also important to them that they should be able to safeguard their audience data and be able to offer transparency to public stakeholders about the way their algorithms work, neither of which they felt confident about when using commercial providers.59

Several public service media organisations have joined forces through the EBU to develop PEACH60 – a personalisation system that can be adopted by individual organisations and adapted to their needs. The aim is to share technical expertise and capacity across the public service media ecosystem, enabling those without their own in-house development teams to still adopt recommendation systems and other data-driven approaches. Although some public service media feel this is still not sufficiently tailored to their work,59 others find it not only caters to their needs but that it embodies their public service mission through its collaborative approach.62

Although we are aware that some public service media continue to use third-party systems, we did not manage to secure research interviews with any organisations that currently do so.

How are public service media recommendation systems currently governed and overseen?

The governance of recommendation systems in public service media is created through a combination of data protection legislation, media regulation and internal guidelines. In this section, we outline the present and future regulatory environment in the UK and EU, and how internal guidelines influence development in the BBC and other public service media. Some public service media have reinterpreted their existing guidelines for operationalising public service values to make them relevant to the use of recommendation systems.

The use of recommendation systems in public service media is not governed by any single piece of legislation or governance. Oversight is generated through a combination of the statutory governance of public service media, general data protection legislation and internal frameworks and mechanisms. This complex and fragmented picture makes it difficult to assess the effectiveness of current governance arrangements.

External regulation

The structures that have been established to regulate public service media are based around analogue broadcast technologies. Many are ill-equipped to provide oversight of public service media’s digital platforms in general, let alone to specifically oversee the use of recommendation systems.

For instance, although Ofcom regulates all UK broadcasters, including the particular duties of public service media, its remit only covers the BBC’s online platforms and not, for example, the ITV Hub or All 4. Its approach to the oversight of BBC iPlayer is to set broad obligations rather than specific requirements and it does not inspect the use of recommendation systems. Both the incentives and sanctions available to Ofcom are based around access to the broadcasting spectrum and so are not relevant to the digital dissemination of content. In practice this means that the use of recommendation systems within public service media are not subject to scrutiny by the communications regulator.

However, like all other organisations that process data, public service media within the European Union are required to comply with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). The UK adopted this legislation before leaving the EU, though a draft Data Protection and Digital Information Bill (‘Data Reform Bill’) introduced in July 2022 includes a number of important changes, including removing the prohibition on automated decision-making, and maintaining restrictions for automated decision-making only if special categories of data are involved. The draft bill also introduces a new ground to allow the processing of special categories of data for the purpose of monitoring and correcting algorithmic bias in AI systems. A separate set of provisions centred around fairness and explainability for AI systems is also expected as part of the Government’s upcoming white paper on AI governance.

The UK GDPR shapes the development and implementation of recommendation systems because it requires:

- Consent: the UK GDPR requires that the use of personal data be made with freely-given, genuine and unambiguous consent from an individual. There are other lawful bases for processing personal data that do not require consent, including legal obligations, processing in a vital interest and processing for a ‘legitimate interest’ (a justification that public authorities cannot rely on if they are processing for their tasks as a public authority).

- Data minimisation: under Article 5(1), the ‘data minimisation’ principle of the UK GDPR states that personal data should be ‘adequate, relevant and limited to what is necessary in relation to the purposes for which they are processed’. Under Article 17 of the UK GDPR, the ‘right to erasure’ grants individuals the right to have personal data erased that is not necessary for the purposes of processing.

- Automated decision-making, the right to be informed and explainability: under the UK GDPR, data subjects have a right not to be subject to solely automated decisions that do not involve human intervention, such as profiling.63 Where such automated decision-making occurs, meaningful information about the logic involved, the significance and the envisaged consequences of such processing need to be provided to the data subject (Article 15 (1) h). Separate guidance from the Information Commissioner’s Office also touches on making AI systems explainable for users.64

Our interviews with practitioners indicated that GDPR compliance is foundational to their approach to recommendation systems, and that careful consideration must be paid to how personal data is collected and used. While the forthcoming Data Reform Bill makes several changes to the UK GDPR, most of these effects on the development and implementation of recommendation systems will likely continue under the current bill’s language.

GDPR regulates the use of data that a recommendation system draws on, but there is not currently any legislation that specifically regulates the ways in which recommendation systems are designed to operate on that data, although there are a number of proposals in train at national and European levels.

In July 2022, the European Parliament adopted the Digital Services Act, which includes (in Article 24a) an obligation for all online platforms to explain, in their terms and conditions, the main parameters of their recommendation system and the options for users to modify or influence those parameters. There are additional requirements imposed on very large online platforms (VLOPs) to provide at least one option for each of their recommendation systems which is not based on profiling (Article 29). There are also further obligations for VLOPs in Article 26 to perform systemic risk assessments, including taking into account the design of the recommendation systems (Article 26 (2) a) and to implement steps to mitigate risk by testing and adapting their recommendation systems (Article 27 (1) ca).

In order to ensure compliance with the transparency provisions in the regulation, the Digital Services Act includes a provision that enables independent auditors and vetted researchers to have access to the data that led to the company’s risk assessment conclusions and mitigation decisions (Article 31). This provision ensures oversight over the self-assessment (and over the independent audit) that companies are required to carry out, as well as scrutiny over the choices large companies make around their recommendation systems.

The draft AI Act proposed by the European Commission in 2021 also includes recommendation systems in its remit. The proposed rules require harm mitigations such as risk registers, data governance and human oversight but only make obligations mandatory for AI systems used in ‘high-risk’ applications. Public service media are not mentioned within this category, although due to their democratic significance it’s possible they might come into consideration. Outside the high-risk categories, voluntary adoption is encouraged. These proposals are still at an early stage of development and negotiation and are unlikely to be adopted until at least 2023.

In another move, in January 2022 the European Commission launched a public consultation on a proposed European Media Freedom Act that aims to further increase the ‘transparency, independence and accountability of actions affecting media markets, freedom and pluralism within the EU’. The initiative is a response to populist governments, particularly in Poland and Hungary attempting to control media outlets, as well as an attempt to bring media regulation up to speed with digital technologies. The proposals aim to secure ‘conditions for [media markets’] healthy functioning (e.g. exposure of the public to a plurality of views, media innovation in the EU market)’. Though there is little detail so far, this framing could allow for the regulation of recommendation systems within media organisations.

In the UK, public service media are excluded from the draft Online Safety Bill which imposes responsibilities on platforms to safeguard users from harm. Ofcom, as well as the Digital Culture Media and Sport Select Committee, have called for urgent reform to regulation that would update the governance of public service media for the digital age. As of this report, there has been no sign of progress on a proposed Media Bill that would provide this guidance.

Internal oversight

Public service media have well-established practices for operationalising their mission and values through the editorial guidelines described earlier. But the introduction of recommendation systems has led many of them to reappraise these and, in some cases, introduce additional frameworks to translate these values for the new context.

The BBC has brought together teams from across the organisation to discuss and develop a set of machine learning engine principles, which they believe will uphold the Corporation’s mission and values:65

- Reflecting the BBC’s values of trust, diversity, quality, value for money and creativity.

- Using machine learning to improve our audience’s experience of the BBC

- Carrying out regular review, ensuring data is handled securely and that algorithms serve our audiences equally and fairly

- Incorporating the BBC’s editorial values and seeking to broaden, rather than narrow horizons.

- Continued innovation and human-in-the-loop oversight.

These have then been adopted into a checklist for teams to use in practice:

‘The MLEP [Machine Learning Engine Principles] Checklist sections are designed to correspond to each stage of developing a ML project, and contain prompts which are specific and actionable. Not every question in the checklist will be relevant to every project, and teams can answer in as much detail as they think appropriate. We ask teams to agree and keep a record of the final checklist; this self-audit approach is intended to empower practitioners, prompting reflection and appropriate action.66

Reflecting on putting this into practice, BBC staff members observed that ‘the MLEP approach is having real impact in bringing on board stakeholders from across the organisation, helping teams anticipate and tackle issues around transparency, diversity, and privacy in ML systems early in the development cycle’.67

Other public service media organisations have developed similar frameworks. Bayerische Rundfunk, the public broadcaster for Bavaria in Germany, found that their existing values needed to be translated into practical guidelines for working with algorithmic systems and developed ten core principles.68 These align in many ways to the BBC principles but have additional elements, including a commitment to transparency and discourse, ‘strengthening open debate on the future role of public service media in a data society’, support for the regional innovation economy, engagement in collaboration and building diverse and skilled teams.69

In the Netherlands, public service broadcaster NPO along with commercial media groups and the Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision drew up a declaration of intent.70 Drawing on the European Union high-level expert group principles on ethics in AI, the declaration is a commitment to the responsible use of AI in the media sector. NPO are developing this into a ‘data promise’ that offers transparency to audiences about their practices.

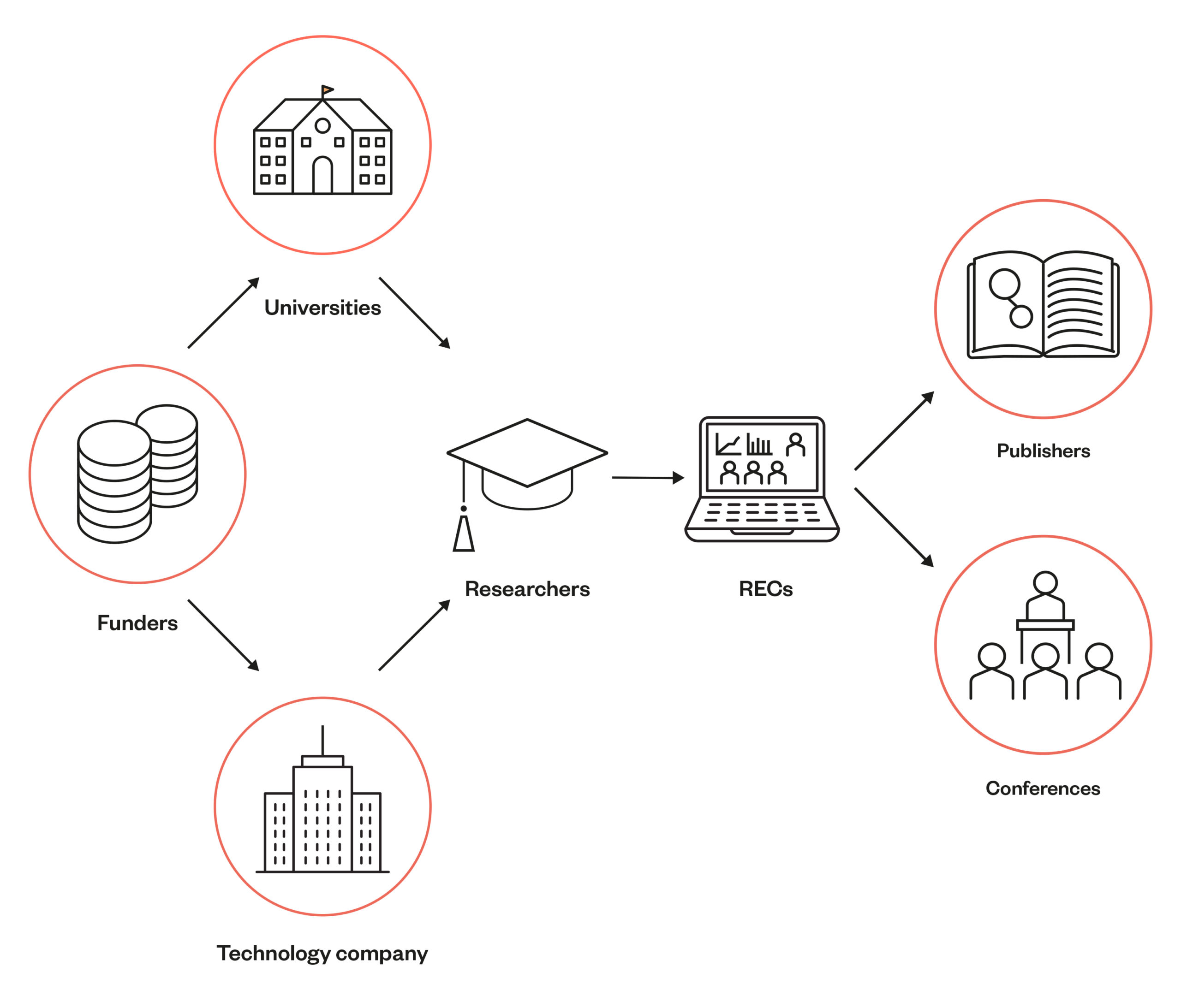

Other stakeholders

Beyond these formal structures, the use of recommendation systems in public service media is shaped by these organisations’ accountability to, and scrutiny by wider society.

All the public service media organisations we interviewed welcomed this scrutiny in principle and were committed to openness and transparency. Most publish regular blogposts about their work, present at academic conferences and invite feedback about their work. These, however, reach a small and specialist audience.

There are limited opportunities for the broader public to understand and influence the use of recommendation systems. In practice, there is little accessible information about recommendation systems on most public service media platforms and even where it exists, teams admit that it is rarely read.

The Voice of the Listener and Viewer, a civil society group that represents audience interests in the UK, has raised concerns with the BBC about a lack of transparency in its approach to personalisation but has been dissatisfied with the response. The Media Reform Coalition has proposed that recommendations systems used in UK public service media should be co-designed with citizens’ media assemblies and that the underlying algorithms should be made public.46