Working with the CARE principles: operationalising Indigenous data governance

Shifting the focus of data governance from consultation to values-based relationships to promote equitable Indigenous participation in data processes.

9 November 2020

Reading time: 19 minutes

Indigenous data sovereignty is becoming an increasingly relevant topic, as limited opportunities for benefit sharing have focused attention on the protection of Indigenous rights and interests, and participation in data governance. 1 2 3 4 5 Globally, there are more than 370 million Indigenous people, representing more than 5,000 distinct cultures, across over 90 countries.6 The recent focus on Indigenous data sovereignty has emerged as part of an intricate weaving together of the Indigenous cultural and intellectual property rights (ICIP) discourse with Indigenous research ethics, and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).7 8 9 10

With most Indigenous data held within non-Indigenous institutions and government agencies, opportunities for increasing control are directly connected to properly identifying Indigenous data and making Indigenous data FAIR (findable, accessible, interoperable, reusable). These objectives are critical to afford greater Indigenous participation in data governance activities. 11 12 13 14 15

A broad range of data-related challenges exists for Indigenous Peoples. Every Indigenous community has enormous collections of tangible and intangible cultural material, knowledge and data, held in archives, museums, libraries, repositories and other online databases. Significant information about these collections, including individual and community names and proper provenance information, is missing.

Indigenous Peoples and communities are largely not the legal rights holders of these materials. Issues of responsibility and ownership, as well as incomplete and significant mistakes in the metadata, continue into the digital lives of these materials. Now that there are more researchers collecting data and samples from Indigenous communities than ever before, there is a renewed need to promote the rights and interests of Indigenous Peoples in relation to their data. 5 17

To begin to address this need, the ‘CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance’ were developed by the Research Data Alliance (RDA) International Indigenous Data Sovereignty Interest Group. They aimed to empower Indigenous Peoples, by shifting the focus of data governance from consultation to values-based relationships that promote equitable Indigenous participation in processes of data reuse, which will result in more equitable outcomes, as well as preserving relationships built on trust and respect.

Development of the CARE principles

The CARE principles (collective benefit, authority to control, responsibility, ethics) were initially developed at a workshop on Indigenous data sovereignty held in Gaborone, Botswana, as part of International Data Week in 2018. The workshop was Indigenous-led and brought together Indigenous and allied researchers and practitioners to draft principles for Indigenous data governance in support of innovation, governance and self-determination among Indigenous Peoples, nations and communities. The design of and action within the Indigenous data sovereignty movement itself centres leadership by Indigenous Peoples.

The RDA International Indigenous Data Sovereignty Interest Group, the workshop host, embodies this philosophy with Indigenous scholar leaders from three continents and Indigenous scholar group members from six continents. They work in collaboration with allied scholars at RDA from across the globe and from diverse disciplines.11 19

This group emerged as a natural site to host a workshop to co-develop a draft set of principles for the governance of Indigenous data. Understanding the need for input, guidance and feedback from Indigenous leaders, communities, scholars and mainstream data users, an iterative process, collecting comments and edits to the drafts, was selected to encourage broad input and participation.

Previous RDA International Indigenous Data Sovereignty Interest Group activities provided a baseline for shared knowledge around concepts such as what are Indigenous Peoples’ data, Indigenous data sovereignty, Indigenous data governance, and what are the challenges for Indigenous Peoples in relation to their data.

The workshop began with an analysis of principles from frameworks issued by Indigenous Data Sovereignty networks, the First Nations Indigenous Governance Centre, Te Mana Raraunga Maori Data Sovereignty Network, the US Indigenous Data Sovereignty Network, and Maiam nayri Wingara Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Data Sovereignty Collective, as well as by mainstream sources (FAIR principles, Open Data Charter principles, STREAM principles) and was developed to inform dialogue among the participants.20

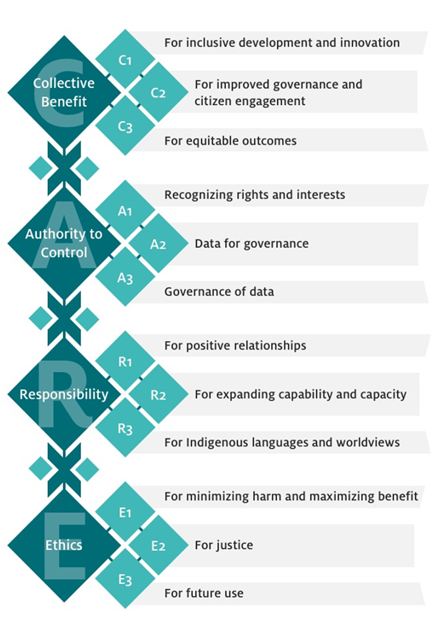

Workshop participants felt that the mainstream frameworks were data-centric, in contrast to the Indigenous-focused frameworks, which were people-and-purpose focused. Four primary principles – Collective Benefit, Authority to Control, Responsibility, and Ethics – were distilled from the discussions to create CARE, a fitting acronym reflecting the essence of Indigenous values.21 Participants broke into small groups to outline and draft the language for both primary and sub-principles (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The CARE principles for Indigenous data governance (Carroll et al. 2020)

The group shared Google documents and Word documents with rightsholders (Indigenous Peoples) and stakeholders (others) through email, social media, personal contacts, presentations and other engagements, to gather edits and comments on the document. To prioritise Indigenous input, the group staged outreach over a period of six months, first to Indigenous data sovereignty network members, Indigenous leaders, Indigenous scholars, and allies, then to mainstream groups. The primary tension in the creation of the principles involved striking a balance between including enough information and content and keeping the document succinct and brief.

Released by the Global Indigenous Data Alliance (GIDA) in September 2019, the CARE principles are designed to guide the inclusion of Indigenous Peoples in data governance across contemporary data ecosystems. 22 The CARE principles bring a people-and-purpose orientation to data governance, which complements the data-centric nature of the FAIR principles. The aim is for data stewards and researchers to be FAIR and CARE when using Indigenous data (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Be FAIR and CARE when using Indigenous data (www.gida-global.org/care)

Creating awareness of the CARE principles in action

GIDA became an organisation member of the RDA in late 2019, to support collaborations that (1) promote Indigenous leadership in data processes and (2) create opportunities for general understanding and application of Indigenous rights and interests across data ecosystems (RDA 2019). The two examples of the RDA-GIDA partnership below move toward the development of data and data systems that leverage Indigenous rights, innovation and development.

Operationalising FAIR & CARE

After the release of the CARE principles, the RDA International Indigenous Data Sovereignty Interest Group and the RDA FAIR Data Maturity Model Working Group began brainstorming what operationalising the FAIR principles with the CARE principles might entail. A joint meeting at the RDA Plenary 15 explored CARE in the context of scientific data, FAIR in the context of Indigenous data, the intersection of FAIR and CARE, and what would be needed to operationalise FAIR with CARE. A manuscript and subsequent workshop are forthcoming, which will start developing the criteria for the implementation of the CARE Principles. One of the key challenges, in contrast with FAIR, is that CARE informs use and needs to be applied across all stages of a data lifecycle.

A key challenge for the RDA Indigenous Data Sovereignty Interest Group moving forward is to identify the kinds of outputs necessary to support uptake of the CARE principles within diverse data communities. The CARE principles provide a framework that can be applied to specific contexts (see COVID-19 guidelines example below), however it will be important to create some consistency of implementation through the development of criteria, guidelines and standards. In this regard we have been working towards the development of a Recommended Practice for the Provenance of Indigenous Peoples’ Data. Given the people-and-purpose centric nature of the CARE principles, their implementation will be structural as well as operational. The CARE principles will in likelihood be adopted in data contexts that support polycentric, nested or distributed approaches to governance, policy and practice.

GIDA-RDA COVID-19 Guidelines for Data Sharing Respecting Indigenous Data Sovereignty

The Research Data Alliance (RDA) COVID-19 Working Group published a set of guidelines on data sharing and related best practices for COVID-19 research (RDA COVID-19 Working Group 2020). The guidelines set forward recommendations for researchers, policymakers, funders, publishers and data-sharing infrastructure providers, covering cross-cutting themes (community participation, Indigenous Peoples, research software and legal and ethical considerations) and different domains (clinical medicine, omics, epidemiology, social sciences). The ‘GIDA-RDA COVID-19 Guidelines for Data Sharing Respecting Indigenous Data Sovereignty’, are framed by the CARE Principles and delineate requirements for Indigenous-designed data approaches that reflect and support Indigenous data sovereignty (RDA COVID-19 Indigenous Data WG 2020).

These guidelines, available in English and Spanish, call attention to the need for approaches consistent with the UNDRIP that support Indigenous Peoples and nations to be engaged in governance on their own terms across COVID-19 data lifecycles and ecosystems. They promote external investments in Indigenous community-controlled data infrastructures and bidirectional capacity enhancement for information sharing among Indigenous and non-Indigenous entities.

Conclusion

Being careful with data is a prerequisite for communities when developing equitable data practices with Indigenous data. The CARE principles build on the work of mainstream stakeholders focused on data reuse and the efforts of Indigenous coalitions focused on Indigenous data sovereignty.

While recognising the value that can be created through the adoption of FAIR principles, the CARE principles have the strength of pointing data producers and repositories towards adoption practices that consider the ‘people’ and ‘purpose’ for which data exist and are used.

As data stakeholders advance standards and practices to facilitate data reuse and research reproducibility, the CARE principles address historical power imbalances, with the goal of creating value from Indigenous data and realising opportunities for Indigenous Peoples within the knowledge economy.

Acknowledgements

The original workshop ‘Indigenous Data Sovereignty Principles for the Governance of Indigenous Data’, was organised by Stephanie Russo Carroll and Maui Hudson, in collaboration with the Research Data Alliance International Indigenous Data Sovereignty Interest Group at the International Data Week held Thursday, 8 November 2018, in Gaborone, Botswana.

The principles described in this manuscript represent voluntary contributions and participation of the authors; workshop participants Oscar L. Figueroa-Rodríguez, Ray Lovett Simeon Materechera, Mark Parsons, Kay Raseroka, Desi Rodriguez-Lonebear, Robyn K. Rowe, Rodrigo Sara, and Jennifer D. Walker; and from the wider US Indigenous Data Sovereignty Network, Te Mana Raraunga Maori Data Sovereignty Network, Maiam nayri Wingara Aboriginal, and Torres Strait Islander Data Sovereignty Collective communities.

We acknowledge the Indigenous Peoples of Botswana on whose land the principles emerged, as well as Indigenous Peoples worldwide.

We are grateful to the Research Data Alliance for workshop location and travel support for some attendees.

Thank you to the following individuals for their comments, edits and suggestions: Randy Akee, Leah Ballantyne, Donna Cormack, Dominique David-Chavez, Bhiamie Eckford-Williamson, Nanibaa’ Garrison, Sharon Hausam, Lydia Jennings, Tahu Kukutai, Kelsey Leonard, Christina Ore, Qunmigu (Kacey Hopson), Andrew Sporle, Michele Suina, Maggie Walter, the Alaska Native Policy Center at the First Alaskans Institute, and the ‘The International Law, United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and Indigenous Data Sovereignty’ Workshop at the Oñati International Institute of the Sociology of Law.

We also acknowledge Amy Jorgensen and Andrew Martinez’s contributions to designing the figures.

This article is the fourth in a series about data stewardship. Across the series researchers and practitioners working in different organisations and contexts, who each have a unique perspective on data stewardship, will share practical experience and research ideas.

It’s not possible or desirable for one person or organisation to decide what a ‘good’ use of data is. That’s why we hope this series and our research will help push forward thinking on how to govern data for good and ensure diverse voices contribute to defining it.

Let us know what you think – Tweet @AdaLovelaceInst using #DataStewardship or email hello@adalovelaceinstitute.org with Data Stewardship in the subject line.

References

- First Nation’s Information Governance Centre. (2018). The First Nations Principles of OCAP®. Available at: https://fnigc.ca/ocap [Last date accessed 2 December 2019].

- Kukutai, T and Walter, M. (2015). ‘Recognition and indigenizing official statistics: Reflections from Aotearoa New Zealand and Australia’. Statistical Journal of the IAOS, 31(2) 317–326.

- Maiam nayri Wingara Communique. (2018). Indigenous Data Sovereignty Communique. Indigenous Data Sovereignty Summit. 20th June 2018, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory. Available at: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5b3043afb40b9d20411f3512/t/5b6c0f9a0e2e725e9cabf4a6/1533808545167/Communique%2B-%2BIndigenous%2BData%2BSovereignty%2BSummit.pdf

- Open Data Charter. (2015). Open Data Charter Principles. 2015. Available at: https://opendatacharter.net/principles/ [Last accessed 17 January 2020].

- Rainie, SC, Rodriguez-Lonebear, D and Martinez, A. (2017b). Policy Brief: Indigenous Data Sovereignty in the United States. Available at http://nni.arizona.edu/application/files/1715/1579/8037/Policy_Brief_Indigenous_Data_Sovereignty_in_the_United_States.pdf [Last accessed date 17 January 2020].

- Research Data Alliance. (2017). International Indigenous Data Sovereignty Interest Group. Available at: https://www.rd-alliance.org/groups/international-indigenous-data-sovereignty-ig [Last accessed 17 January 2020].

- Research Data Alliance. (2019). RDA Announces Memorandum of Understanding with the Global Indigenous Data Alliance. Available at: https://www.rd-alliance.org/rda-announces-memorandum-understanding-global-indigenous-data-alliance [Last accessed 17 January 2020].

- Research Data Alliance International Indigenous Data Sovereignty Interest Group. (September 2019). “CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance.” The Global Indigenous Data Alliance. GIDA-global.org.

- RDA COVID-19 Indigenous Data WG. “Data sharing respecting Indigenous data sovereignty.” In RDA COVID-19 Working Group (2020). Recommendations and guidelines on data sharing. Research Data Alliance.

- RDA COVID-19 Working Group. (2020). Recommendations and guidelines on data sharing. Research Data Alliance.

- Te Mana Raraunga. (2018). Principles of Māori Data Sovereignty Brief #1. October 2018. Available at: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5d3799de845604000199cd24/t/5d6f940cc5442b00013e4dab/1567593484780/TMR%2BMa%CC%84ori%2BData%2BSovereignty%2BPrinciples%2BOct%2B2018.pdf [Last accessed 17 January 2020]

- The Economist. (2017). The world’s most valuable resource is no longer oil, but data, 6 May 2017. Available at: https://www.economist.com/news/leaders/21721656-data-economy-demands-new-approach-antitrust-rules-worlds-most-valuable-resource [Last date accessed 17 January 2020].

Footnotes

- Carroll, SR, Rodriguez-Lonebear, D and Martinez, A. (2019) Indigenous Data Governance: Strategies from United States Native Nations. Data Science Journal, 18(31): 1–15

- Lovett, R, Lee, V, Kukutai, T, Cormack, D, Rainie, SC, and Walker, J. (2019). ‘Good data practices for Indigenous Data Sovereignty and Governance.’ In: Daly, A, Devitt, K, and Monique, M (eds.), Good Data, Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures Inc.

- Rainie, SC, Kukutai, T, Walter, M, Figueroa-Rodriguez, OL, Walker, J and Axelsson, P. (2019). Issues in Open Data: Indigenous Data Sovereignty. In: Davies, T, Walker, S, Rubinstein, M and Perini, F (eds.), The State of Open Data: Histories and Horizons, pp. 300–319. Cape Town and Ottawa: African Minds and International Development Research Centre.

- Kukutai, T and Taylor, J. (2016a). Indigenous data sovereignty: Toward an agenda. Canberra, Australia: Australian National University Press.

- Hudson, M., Garrison, N., Sterling, R., Caron, N.R., Fox, K., Yracheta, J., Anderson, J., Wilcox, P., Arbour, L., Brown, A., Taualii, M., Kukutai, T., Haring, R., Te Aika, B., Baynam, G.S., Dearden, P.K, Chagne, D., Malhi, R.S. Garba, I., Tiffin, N., Bolnick, D., Stott, M., Rolleston, A.K. Ballantyne, L.L., Lovett, R., David-Chavez, D., Martinez, A., Sporle, A., Walter, M., Reading, J., Russo Carroll, S. (2020). ‘Rights, Interests, & Expectations: Indigenous perspectives on unrestricted access to genomic data.’ Nature Reviews Genetics.

- United Nations. (2009). State of the World’s Indigenous Peoples. Unknown. Available at: https://www. un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/SOWIP/en/SOWIP_web.pdf [Last accessed 28 August 2018].

- Tsosie, R. (1997). ‘Indigenous Peoples Claims to Cultural Property: A Legal Perspective.’ Museum Anthropology, 21(3): 5-11.

- Janke, T. (2004). Minding Culture: Case Studies in Intellectual Property and Traditional Cultural Expressions. World Intellectual Property Organization: Geneva. Available at: https://www.wipo.int/publications/en/details.jsp?id=286 [Last accessed 22 January 2020]

- United Nations General Assembly. (2007). United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples: Resolution/Adopted by the General Assembly, 2 October 2007, A/RES/61/295, Available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/471355a82.html [Last date accessed 17 January 2020].

- Davis, M. (2016). Data and the United Nations Declarations on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. In: Kukutai, T and Taylor, J (eds.), Indigenous data sovereignty: Toward an agenda, 25-38. Canberra, Australia: Australian National University Press.

- Carroll, SR, Rodriguez-Lonebear, D and Martinez, A. (2019).

- Rainie, SC, Schultz, JL, Briggs, E, Riggs, P and Palmanteer-Holder, NL. (2017a). ‘Data as strategic resource: Self-determination and the data challenge for United States Indigenous nations.’ International Indigenous Policy Journal, 8(2).

- Kukutai, T and Taylor, J. (2016). ‘Data Sovereignty for Indigenous Peoples: Current Practice and Future Needs.’ In: Kukutai, T and Taylor, J (eds.), Indigenous data sovereignty: Toward an agenda, 1–22. Canberra, Australia: Australian National University Press.

- Rodriguez-Lonebear, D. (2016). ‘Building a data revolution in Indian country.’ In: Kukutai, T and Taylor, J (eds.), Indigenous data sovereignty: Toward an agenda, pp. 253–272. Canberra, Australia: Australian National University Press.

- Snipp, CM. (2016). ‘What does data sovereignty imply: what does it look like?.’ In: Kukutai and Taylor, J (eds.), Indigenous Data Sovereignty Toward an Agenda, pp. 39-55 Canberra, Australia: Australian National University Press.

- Hudson, M., Garrison, N., Sterling, R., Caron, N.R., Fox, K., Yracheta, J., Anderson, J., Wilcox, P., Arbour, L., Brown, A., Taualii, M., Kukutai, T., Haring, R., Te Aika, B., Baynam, G.S., Dearden, P.K, Chagne, D., Malhi, R.S. Garba, I., Tiffin, N., Bolnick, D., Stott, M., Rolleston, A.K. Ballantyne, L.L., Lovett, R., David-Chavez, D., Martinez, A., Sporle, A., Walter, M., Reading, J., Russo Carroll, S. (2020). ‘Rights, Interests, & Expectations: Indigenous perspectives on unrestricted access to genomic data.’ Nature Reviews Genetics.

- Garrison, N., Hudson, M., Ballantine, L., Garba, I., Martinez, A., Taualii, M., Arbour, L., Caron, N.R., Rainie, S.C. (2019). ‘Genomic Research through an Indigenous Lens: Understanding the Expectations.’ Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics, Volume 20.

- Carroll, SR, Rodriguez-Lonebear, D and Martinez, A. (2019).

- Kukutai, T and Taylor, J. (2016). ‘Data Sovereignty for Indigenous Peoples: Current Practice and Future Needs.’ In: Kukutai, T and Taylor, J (2016a)

- Carroll, S.R., Garba, I., Figueroa-Rodriguez., Holbrook, J., Lovett, R., Materechera, S.A., Parsons, M., Raseroka, K., Rodriguez-Lonebear, D., Rowe, R.K., Sara, R., Walker, J.D., Anderson, J., & Hudson, M. (2020). ‘The CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance.’ Data Science Journal, 19(43), 1–12.

- Carroll, S.R., Garba, I., Figueroa-Rodriguez,. Holbrook, J., Lovett, R., Materechera, S.A., Parsons, M., Raseroka, K., Rodriguez-Lonebear, D., Rowe, R.K., Sara, R., Walker, J.D., Anderson, J., & Hudson, M. (2020)

- Carroll, S.R., Garba, I., Figueroa-Rodriguez,. Holbrook, J., Lovett, R., Materechera, S.A., Parsons, M., Raseroka, K., Rodriguez-Lonebear, D., Rowe, R.K., Sara, R., Walker, J.D., Anderson, J., & Hudson, M. (2020). ‘The CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance.’ Data Science Journal, 19(43), 1–12.

Related content

Data stewardship: an archival perspective

Archives as datasets? What can we learn from archivists in data preservation and sharing?

Practising data stewardship in India, early questions

How could data stewardship help to rebalance power towards individuals and communities?

Common governance of data: appropriate models for collective and individual rights

From Elinor Ostrom’s design principles for governing the commons to mechanisms that ensure collective and individual data rights: what steps to take?

Strength in numbers: a case study for building a data-based community in cystic fibrosis

Now, more than ever, data can be used to bring people together as well as numbers.