From ‘walled gardens’ to open meadows

How interoperability could be the key to addressing platform power

8 November 2021

Reading time: 20 minutes

Today’s digital ecosystem is characterised by the unrivalled dominance of a handful of Big Tech platforms headquartered in the United States and China. They retain market power by virtue of dynamics such as network effects, where the value of a company or service to existing users increases when new users join, in a self-reinforcing loop (for example Facebook, Uber and TikTok).

Network effects can significantly benefit a dominant platform and potentially offer users higher quality services, however it may become increasingly difficult for competitive services to emerge if a large user base is already captured, and switching services might imply both practical limitations (such as for example moving data to another platform), as well as personal costs (for example losing communication with groups of interest, in the case of social media).

Potentially anti-competitive practices – such as Apple controlling how apps are sold on iPhones and iPads via its App Store, or Google prioritising its own content on search, and Amazon prioritising its own products – add to the challenges. Other power consolidation tendencies emerge from the ability of platforms to develop extensive customer intelligence based on extractive data practices, such as algorithms designed to show content optimised to maximise attention, using dark patterns to influence users’ choices for economic profits.

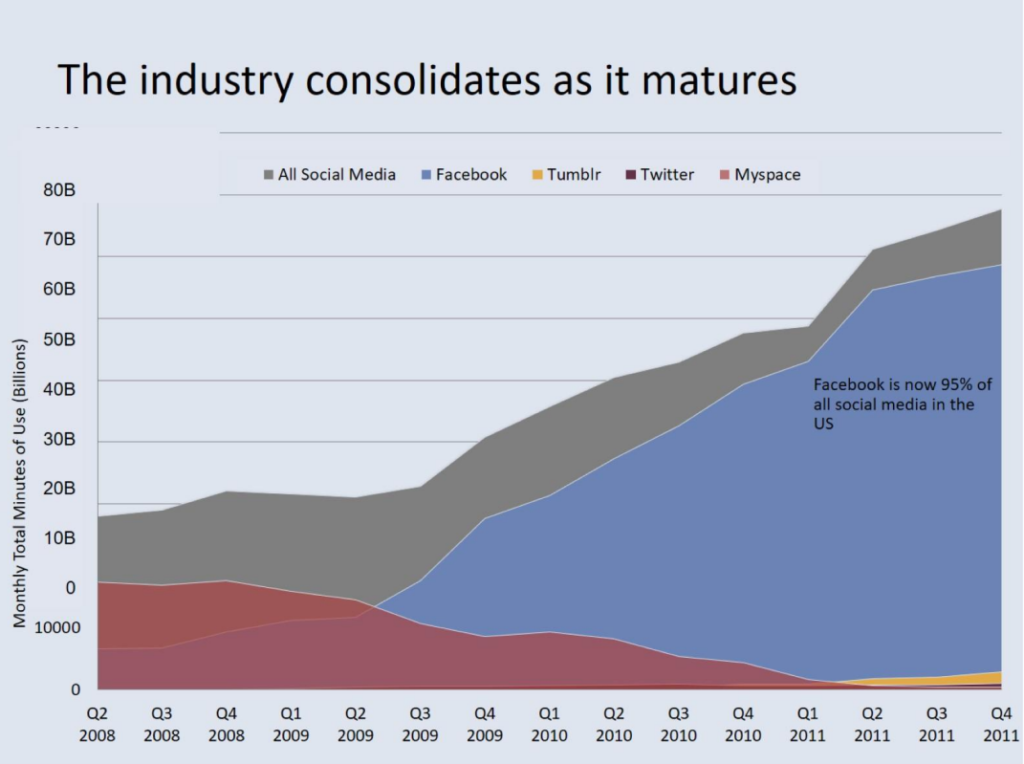

These dynamics can contribute to ‘winner takes all’ markets, where one company builds an insurmountable lead, both through organic growth based on ever-greater access to user data and network effects, and acquiring competitors. This can be seen in the historically unprecedented capitalisation of ecosystems of linked US (GAFAM, worth roughly $9.5tn in September 2021) and Chinese (Tencent, Alibaba and Meituan, valued at roughly $1.3tn in September 2021) digital services dominating global digital markets, with billions of users. As Facebook noted even a decade ago (see Figure 1), this dynamic can give individual firms remarkably high shares of digital markets. Stronger recent privacy regulations such as the EU GDPR will also make it more difficult for new entrants to follow this path.

The limits this places on fair competition in these markets greatly limits service diversity, and hence individuals’ choice of services based on both economic and non-economic factors, such as privacy (e.g. the ‘price’ of ‘free’ services) and freedom of expression (e.g. the choice of which types of content are blocked or prioritised) on social media platforms.

Overall, lack of competition reduces incentives for innovation and higher quality/lower price services, while putting a small number of companies (and the governments that can effectively shape their behaviour)1 in an extremely powerful position to affect human rights around the world. And users are less able to satisfy their own unique preferences for combinations of competitive services if there are strong incentives to choose a single platform.2

These dynamics are not unique to digital platforms, but in many other sectors have been overcome through the imposition of interoperability rules, such as in the electronic communications sector and more recently in the banking sector. In communications, these and other detailed competition regulations contributed significantly to ‘rapid diffusion of new technologies and new services’, which ‘led to falling prices and much greater take up, which had wider beneficial effects on the European economy’.3 The UK’s Open Banking programme, which required the nine largest retail banks to agree a common programming interface (API), has enabled hundreds of small ‘fintech’ companies to offer a wide range of new financial services to over 4 million individuals and small businesses, linked to their existing bank accounts.

As in telecommunication and the finance sector, large platforms may well enable interoperability for complementary services (vertical interoperability)4 – for example, Facebook’s apps – since these increase the value of the platform for users, and often provide further user data for the platform to analyse. But such environments are often technically and legally limited to restrict their use for competition with the platform itself (horizontal interoperability).5

How can interoperability help?

Interoperability lets products and services from competing firms work together. It helps users choose freely from, easily switch between, or simultaneously make use of competing services, while retaining access to their own data and contacts. By reducing switching costs and sharing the benefits of network effects between companies, it supports competition on the merits by lowering barriers to entry to a market, while sharing some of the benefits of scale efficiencies across an industry and wider society.

As well as the economic benefits of stimulating greater competition, interoperability could increase the diversity of available services, and hence enhance user choice based on values such as privacy and freedom of expression. For example, it could allow end users to choose a privacy-focused social media service, or ‘to determine their own tolerances for different types of speech but make it much easier for most people to avoid the most problematic speech, without silencing anyone entirely or having the platforms themselves make the decisions about who is allowed to speak’.6

In a competitive market, interoperability is a valuable function for customers, which firms are incentivised to support. But in a concentrated market, a large company’s customer base is a valuable source of market power, since it can exclude competitor services’ users from communicating with them via that platform, while using customer data to improve product quality and move into related markets in a way that is much more difficult for smaller competitors.

Digital competition reviews for governments around the world have recommended interoperability mandates as a key regulatory tool to address highly concentrated digital markets, which demonstrate extreme returns to scale and scope. Elements of such mandates already exist, such as the EU General Data Protection Regulation’s data portability right, and in specific industry sectors (such as the EU’s second payment services directive, and the European Electronic Communications Code). However, there is broad consensus that these need to be developed further and applied more widely to be effective.7

How would interoperability work?

Interoperability in digital markets usually requires some combination of access to data and platform functionality.

Data interoperability

Data portability (Article 20 of the EU GDPR) is the right of a user to move their personal data from one firm to another. (GAF*M’s Data Transfer Project is slowly developing technical tools to support this.) While this should help an individual switch from one company to another, including by giving price-comparison tools access to previous customer bills, a wider range of uses could be enabled by real-time data mobility8 or interoperability,9 implying an individual can give one company permission to access their data held by another, updated whenever they use the second service. These remedies can stand alone, where the main objective is to enable individuals to give access to their personal data held by an incumbent firm to competitors.

Kerber and Schweitzer make an additional distinction between syntactic or technical interoperability, the ability for systems to connect and exchange data (often via Application Programming Interfaces/APIs) and semantic interoperability, that connected systems share a common understanding of the meaning of data they exchange.10

An important element of making data-focused interoperability work is the development of such standardised (frequently industry-specific) ontologies specifying the meaning of data.11 This work is essential underpinning for all types of portability and interoperability. Just like the development of technical standards for protocols, the development of these ontologies needs industry collaboration, and measures to ensure powerful companies do not hijack them to their own benefit.

An optional interoperability function is to require companies to support personal data stores, where users store and control their own data using a third-party provider, or their own software (e.g. the MyData model,12 and Web inventor Tim Berners-Lee’s Solid project). Such remedies can be justified under data protection as well as competition doctrines.

The data, or consent to access it, could be managed by a single aggregator (major Indian banks are developing this model with their account aggregator for financial services),13 or a more complex web of services enabled by user software (as in the UK’s Open Banking). It is also possible for service providers to send queries or code to run on personal data stores inside a protected sandbox, limiting the service provider’s access to data (e.g. a mortgage provider could send code checking an applicant’s monthly income was above a certain level to their PDS, or current account provider, without gaining access to all of their transaction data).14

The largest companies also have a significant advantage in their access to very large quantities of user data, particularly when it comes to training machine learning systems. In such cases, it may – separately from other remedies – be justified to give competitors access to that raw data, although dealing effectively with the resulting privacy issues (for example, by pseudonymising the data) is difficult. In other circumstances, requiring access to statistical summaries of the data (e.g. popularity of specific social media content) may be sufficient, while limiting the privacy problems caused. Finally, firms could be required to share the (highly complex) details of machine-learning models, or access to them to answer specific questions (such as the likelihood a given piece of social-media content is hate speech).

Such measures would reduce the incentives for regulated companies to gather data, which in most cases is relatively low-cost, and to develop machine-learning models, which can be highly resource-intensive, since they can no longer capture the full value of the data/models they produce. The overall impact on innovation would depend on whether increased competition resulting from data sharing at least counterbalanced these reduced incentives, on a case-by-case basis.

Functionality-oriented interoperability

Competitor access to platform functionality would include the ability for a user of one instant-messaging service to send a message to a user or group on a competing service; the user of one social media service to ‘follow’ a user on another service, and ‘like’ their shared content; the ability of a user of a financial services tool to initiate a payment from an account held with a second company; and the user of one editing tool to collaboratively edit a document or media file with the user of a different tool, hosted on a third platform. This type of access is often referred to as interoperability (sometimes called protocol interoperability,15 or in telecoms regulation, interconnection of networks).

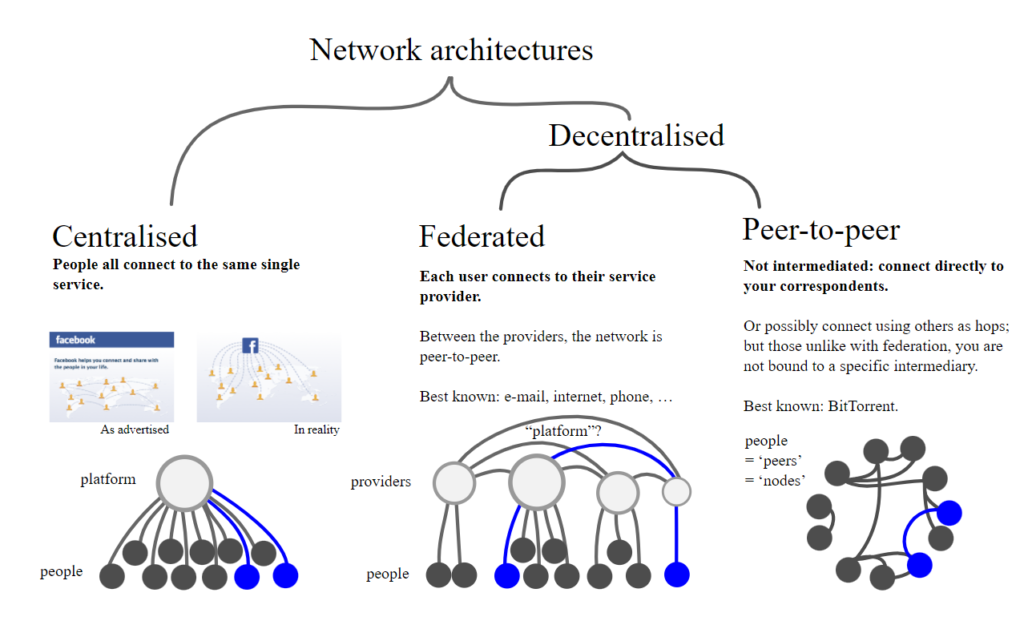

Services communicate with each other using open/publicly accessible APIs and/or standardised protocols. In Internet services, this generally looks like the ‘decentralised’ network architectures shown in Figure 2:

The UK’s Open Banking Standard recommended: ‘The Open Banking API should be built as an open, federated and networked solution, as opposed to a centralised/hub-like approach. This echoes the design of the Web itself and enables far greater scope for innovation.’16

An extended version of functional interoperability would allow users to signal their preferences to platforms on for example profiling, using a tool such as the Global Privacy Control, and their preferred default services such as search; replace core platform functionality, such as a timeline ranking algorithm or an operating system default mail client, with a preferred version from a competitor (known as modularity);17 and use their own choice of software to interact with the platform.

Noted competition economist Cristina Caffara has concluded ‘we need wall-to-wall [i.e. near-universal] interoperability obligations at each pinch point and bottleneck: only if new entrants can connect and leverage existing platforms and user bases can they possibly stand a chance to develop critical mass. Data portability alone is just a marginal solution (and no wonder it is the ‘go to’ remedy for GAFAM when they want to flag their good intentions).’18 A review of portability in the Internet of Things sector came to a similar conclusion.19

What are the challenges to making interoperability a reality?

While adopting interoperability to address concentrations of market power in the digital domain may seem a promising approach, implementing it would require a number of pre-conditions to be in place, and would face some barriers. Table 1 below summarises the sources of market power for large companies that can be addressed by interoperability and related remedies, and the specific issues policymakers and regulators must consider when doing so.

While much of the policy debate so far on interoperability remedies has taken place within a competition-law framework (including telecoms competition), there are equally important issues to consider under data and consumer protection law, as well as useful ideas from media regulation. Competition-focused measures are generally applied only to the largest companies, while other measures can be more widely applied. In some circumstances these measures can be imposed under existing competition-law regimes on dominant companies in a market, although this approach can be extremely slow and resource-intensive for enforcement agencies.

Proposed legislation in both the EU (the Digital Markets Act) and the US (the ACCESS Act and related bills) would impose some of these measures up-front on the very largest gatekeeper firms. The European Commission also plans to introduce a Data Act which would include some of the access to data provisions below. Smaller firms are free to decide whether to make use of interoperability features their largest competitors may be obliged to support.

| Sources of market power for large firms/platforms | Interoperability or related remedies | Specific issues (⭐=minor, ⭐⭐=major) |

| Access to individual customer data to provide customised services and adjacent services | Real-time data portability/data interoperability (under individual customer control)

Requirement to support user-data stores (Much) stricter enforcement of data minimisation and purpose limitation elements of data-protection law |

Customer needs accounts with all services they wish to interact with, and face take-it-or-leave-it contract terms requiring e.g. consent for profiling (which can also be addressed with consumer protection measures) ⭐⭐

Incentive to greatly increase profiling of users (needing greater enforcement of data minimisation/ purpose limitation in data protection law) ⭐ |

| Access to large-scale raw customer data for analytics/product improvement | Mandated competitor access to statistical (e.g. search query and clickstream data) or raw data (likely in pseudonymised form) | Significant data-protection issues (difficulty of anonymisation) with raw data ⭐⭐

Reduced incentives for data collection ⭐ |

| Access to large-scale aggregate/statistical customer data for machine learning etc. | Mandated competitor access to models, or specific functionality of them via APIs (e.g. checking content against hate-speech models) | Potential data protection issues (since firms would be given access to competitors’ customer records without those individuals’ consent) (need to consider mitigations such as differential privacy) ⭐

Reduced incentives for data collection and model training ⭐⭐ |

| Ability to restrict competitor interaction with customers (e.g. send/receive messages, share content, collaborative editing, make payments, allocate jobs) | Requirement to support open/publicly accessible APIs or standardised communications protocols (such as from the ITU, IETF or W3C) | Complexity of designing APIs/standards, while preventing anticompetitive exclusion ⭐ |

| Availability and use of own core platform services (eg monetisation and identity) to increase ‘stickiness’ | Government coordination and funding for development of open infrastructural standards and components

Requirement for platforms to support/integrate these standard components |

Technical complexity of full integration of standard/competitor components into services/design of APIs to enable this, while preventing anticompetitive exclusion ⭐⭐

Potential pressure for incorporation of government surveillance functionality in standards ⭐ |

| Ability to control user interface, including ads (monetisation) and content filtering/ recommendation (engagement), self-preferencing own adjacent services (e.g. presenting own specialised search engine results first, setting/entrenching defaults), ignoring user signals of preferred settings (e.g. Global Privacy Control) | Requirement to support competitors’ monetisation and filtering/recommendation services via open APIs (similar to ‘must carry’ obligations in media law?)20

Requirement to present competitors’ services to users on an equal basis (similar to ‘equal prominence’ obligations in media law?)21 Requirement to recognise specific user signals such as Global Privacy Control or an updated ‘Do Not Track’ Open APIs to enable alternative software clients, giving users much greater choice over their user experience |

Technical complexity of full integration of competitor components into services/design of APIs to enable this, while preventing anticompetitive exclusion ⭐⭐ |

The devil in the detail

As Table 1 shows, the ideal form of interoperability remedies is context-specific. Reviewing the proposed EU Digital Markets Act, Caffarra concluded: ‘There are vast differences across [digital platform] business models that make it hard to discipline the exercise of market power and foster meaningful entry through a handful of general rules extrapolated from a handful of antitrust cases.’22

Interoperability (and more effective competition broadly) is not a replacement for protecting individuals through data and consumer protection law, but can act as a useful complement to it, incentivising innovation to give individuals (and businesses) a broader choice of digital services that better meet their needs and preferences – as well as reducing the outsized power of today’s gigantic technology platforms in relation to their users, their workers and the democratic process.23

This is the first in a series of posts from Ian Brown, a leading specialist on internet regulation and pro-competition mechanisms.

The second post in the series investigates how interoperability might be implemented in practical terms, and what kinds of interoperability would most effectively break down platform power.

Image credit: cnythzl

Footnotes

- Fukayama, F. (2021). ‘Making the Internet Safe for Democracy’. Journal of Democracy 32, no. 2. Pp. 37–44. Available at: https://www.journalofdemocracy.org/articles/making-the-internet-safe-for-democracy/

- Davies, T, and Zlatina G. (2021). ‘Zero Price, Zero Competition: How Marketization Fixes Anticompetitive Tying in Monetized Markets’. Haifa. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3868332

- Cave, M,. Genakos, C., and Valletti, T. (2019). ‘The European Framework for Regulating Telecommunications: A 25-year Appraisal’, Review of Industrial Organization, vol. 55, p.60. Available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/100360/

- Kerber, W., and Schweitzer, H. (2017). ‘Interoperability in the Digital Economy’. JIPITEC. 8, no. 1. Available at: https://www.jipitec.eu/issues/jipitec-8-1-2017/4531

- Kerber, W., and Schweitzer, H. (2017)

- Masnick, M. (2019). ‘Protocols, Not Platforms: A Technological Approach to Free Speech’, Knight First Amendment Institute. Available at: https://knightcolumbia.org/content/protocols-not-platforms-a-technological-approach-to-free-speech

- Brown, I. (2020). ‘Interoperability as a Tool for Competition Regulation’. OpenForum Academy. Available at: https://doi.org/10.31228/osf.io/fbvxd

- Furman, J., Coyle, D., Fletcher, A., McAuley, D., and Marsden, P. (2019). ‘Unlocking Digital Competition: Report of the Digital Competition Expert Panel’. HM Treasury. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/785547/unlocking_digital_competition_furman_review_web.pdf

- Kerber, W, and Schweitzer, H., (2017). ‘Interoperability in the Digital Economy’. JIPITEC. 8, no. 1. Available at: https://www.jipitec.eu/issues/jipitec-8-1-2017/4531

- Kerber, W, and Schweitzer, H., (2017)

- Gal, M.S., and Rubinfeld, D. L. (2019). ‘Data Standardization’. NYU Law Review 94, no. 4. Available at: https://www.nyulawreview.org/issues/volume-94-number-4/data-standardization/

- Kuikkaniemi, K., Poikola, A., and Honko, H. (n.d). ‘MyData – A Nordic Model for Human-Centered Personal Data Management and Processing’. Ministry of Transport and Communications. Available at: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/MyData-A-Nordic-Model-for-human-centered-personal-Kuikkaniemi-Poikola/6517f27c12e82b4d834b00c1839115edc016f7b6

- Singh, M. (2021). ‘India’s Account Aggregator Aims to Bring Financial Services to Millions’. TechCrunch, 2 September. Available at: https://social.techcrunch.com/2021/09/02/india-launches-account-aggregator-system-to-extend-financial-services-to-millions/

- Yuchen, Z., Haddadi, H., Skillman, S., Enshaeifar, S., and Barnaghi, P. (2020). ‘Privacy-Preserving Activity and Health Monitoring on Databox’. In Proceedings of the Third ACM International Workshop on Edge Systems, Analytics and Networking, 49–54. EdgeSys ’20. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1145/3378679.3394529

- Crémer, J., de Montjoye, Y, and Heike Schweitzer, H. (2019). Competition Policy for the Digital Era. LU: Publications Office. Available at: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2763/407537

- The ODI. (2016). The Open Banking Standard. Available at: http://theodi.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/298569302-The-Open-Banking-Standard-1.pdf

- Farrell, J., and Weiser, P. (2003). ‘Modularity, Vertical Integration, and Open Access Policies: Towards a Convergence of Antitrust and Regulation in the Internet Age’. Harvard Journal of Law and Technology 17, no. 1. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.452220

- Caffarra, C. (2021). ‘What Are We Regulating For?’ VOXeu, CEPR Policy Portal (blog), 3 September. Available at: https://voxeu.org/content/what-are-we-regulating

- Turner, S., Quintero, J. G., Turner, S., Lis, J., and Tanczer, L. M. (2020). ‘The Exercisability of the Right to Data Portability in the Emerging Internet of Things (IoT) Environment’ New Media & Society, 10 July. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820934033

- Requiring, for example, a cable or satellite TV distributor to carry public service broadcasting channels.

- Requiring, for example, a cable or satellite TV distributor to show competitors’ channels equally prominently in Electronic Programme Guides as their own.

- Caffarra, C. (2021).

- Brown, I., and Marsden,C. T. (2013). Regulating Code: Good Governance and Better Regulation in the Information Age. Information Revolution and Global Politics. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press.

Related content

Making interoperability work in practice: forms, business models and safeguards

Equitable interoperability as a standard

Rethinking data and rebalancing digital power

What is a more ambitious vision for data use and regulation that can deliver a positive shift in the digital ecosystem towards people and society?

Beyond the regulation of big platforms – supporting different visions for digital ecosystems

An introduction to the Rethinking data programme

Rethinking data: working group for data regulations

An interdisciplinary and international group of experts to advise on the development of data governance and regulations